الأخلاقيات النووية

| الأسلحة النووية |

|---|

|

| خلفية |

| الدول المسلحة نووياً |

|

إن الأخلاقيات النووية هي مجال متعدد التخصصات من الدراسة الأكاديمية والمتعلقة بالسياسة والتي يتم فيها فحص المشكلات المرتبطة بالحرب النووية أو الردع النووي أو الحد من التسلح النووي أو نزع السلاح النووي أو التقنية النووية من خلال واحد أو أكثر من النظريات أو الأطر الأخلاقية أو المعنوية.[1][2][3] وفي الدراسات الأمنية المعاصرة، غالبًا ما تُفهم مشاكل الحرب النووية والردع والانتشار وغيرها على وجه التحديد من الناحية السياسية أو الإستراتيجية أو العسكرية.[4] ولكن أيضًا في الدراسة الخاصة بالمنظمات الدولية والقانونية تُفهم هذه المشكلات أيضًا من الناحية القانونية.[5] وتفترض الأخلاقيات النووية أن الاحتمالات الحقيقية للغاية بانقراض الإنسان أو الانقراض الجماعي للإنسان أو الانحلال البيئي الشامل التي يمكن أن تنجم عن الحرب هي المشكلات الأخلاقية العميقة أو المعنوية. وعلى وجه التحديد فإنها تفترض أن نتائج انقراض الإنسان أو الانقراض الجماعي للإنسان أو الانحلال البيئي تعد جميعها من الشرور الأخلاقية. وقد توصل بعض العلماء إلى أنه بالتالي يعد من الخطأ أخلاقيًا العمل بأساليب تؤدي إلى هذه النتائج، وهو ما يعني أنه من الخطأ أخلاقيًا الدخول في حرب نووية.[6]

تهتم الأخلاقيات النووية بدراسة سياسات الردع النووي والحد من التسليح ونزع السلاح والتقنية النووية بقدر ارتباطها بقضية الحرب النووية أو منعها. المبررات الأخلاقية للردع النووي، على سبيل المثال، تركد على دورها في منع حرب نووية قوية عظمى منذ نهاية الحرب العالمية الثانية.[7] وفي الواقع فإن بعض العلماء يزعمون أن الردع النووي يبدو أنه استجابة منطقية من الناحية الأخلاقية إلى عالم التسليح النووي.[8] والإدانة الأخلاقية للردع النووي في المقابل تؤكد على انتهاكات حتمية على ما يبدو لحقوق الإنسان والديمقراطية الناشئة.[9]

Early ethical issues

The application of nuclear technology, both as a source of energy and as an instrument of war, has been controversial.[10][11][12][13]

Uranium mining and milling

Notable nuclear weapons accidents

- February 13, 1950: a Convair B-36B crashed in northern British Columbia after jettisoning a Mark IV atomic bomb. This was the first such nuclear weapon loss in history.

- May 22, 1957: a 42,000-pound Mark-17 hydrogen bomb accidentally fell from a bomber near Albuquerque, New Mexico. The detonation of the device's conventional explosives destroyed it on impact and formed a crater 25-feet in diameter on land owned by the University of New Mexico. According to a researcher at the Natural Resources Defense Council, it was one of the most powerful bombs made to date.[14]

- 7 June 1960: the 1960 Fort Dix IM-99 accident destroyed a Boeing CIM-10 Bomarc nuclear missile and shelter and contaminated the BOMARC Missile Accident Site in New Jersey.

- 24 January 1961: the 1961 Goldsboro B-52 crash occurred near Goldsboro, North Carolina. A B-52 Stratofortress carrying two Mark 39 nuclear bombs broke up in mid-air, dropping its nuclear payload in the process.[15][16]

- 1965 Philippine Sea A-4 crash, where a Skyhawk attack aircraft with a nuclear weapon fell into the sea.[17] The pilot, the aircraft, and the B43 nuclear bomb were never recovered.[18] It was not until the 1980s that the Pentagon revealed the loss of the one-megaton bomb.[19]

- January 17, 1966: the 1966 Palomares B-52 crash occurred when a B-52G bomber of the USAF collided with a KC-135 tanker during mid-air refuelling off the coast of Spain. The KC-135 was completely destroyed when its fuel load ignited, killing all four crew members. The B-52G broke apart, killing three of the seven crew members aboard.[20] Of the four Mk28 type hydrogen bombs the B-52G carried,[21] three were found on land near Almería, Spain. The non-nuclear explosives in two of the weapons detonated upon impact with the ground, resulting in the contamination of a 2-square-kilometer (490-acre) (0.78 square mile) area by radioactive plutonium. The fourth, which fell into the Mediterranean Sea, was recovered intact after a 2½-month-long search.[22]

- January 21, 1968: the 1968 Thule Air Base B-52 crash involved a United States Air Force (USAF) B-52 bomber. The aircraft was carrying four hydrogen bombs when a cabin fire forced the crew to abandon the aircraft. Six crew members ejected safely, but one who did not have an ejection seat was killed while trying to bail out. The bomber crashed onto sea ice in Greenland, causing the nuclear payload to rupture and disperse, which resulted in widespread radioactive contamination.

- September 18–19, 1980: the Damascus Accident, occurred in Damascus, Arkansas, where a Titan missile equipped with a nuclear warhead exploded. The accident was caused by a maintenance man who dropped a socket from a socket wrench down an 80-foot shaft, puncturing a fuel tank on the rocket. Leaking fuel resulted in a hypergolic fuel explosion, jettisoning the W-53 warhead beyond the launch site.[23][24][25]

Nuclear fallout

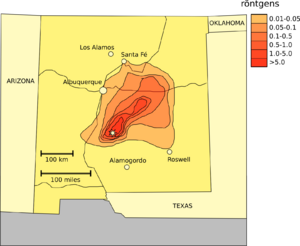

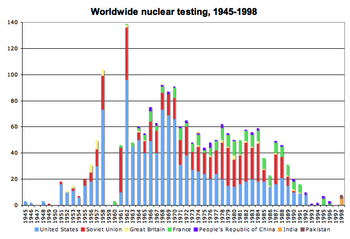

Over 500 atmospheric nuclear weapons tests were conducted at various sites around the world from 1945 to 1980. Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when the Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb test at the Pacific Proving Grounds contaminated the crew and catch of the Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon.[26] One of the fishermen died in Japan seven months later, and the fear of contaminated tuna led to a temporary boycotting of the popular staple in Japan. The incident caused widespread concern around the world, especially regarding the effects of nuclear fallout and atmospheric nuclear testing, and "provided a decisive impetus for the emergence of the anti-nuclear weapons movement in many countries".[26]

As public awareness and concern mounted over the possible health hazards associated with exposure to the nuclear fallout, various studies were done to assess the extent of the hazard. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/ National Cancer Institute study claims that fallout from atmospheric nuclear tests would lead to perhaps 11,000 excess deaths amongst people alive during atmospheric testing in the United States from all forms of cancer, including leukemia, from 1951 to well into the 21st century.[27][28] As of March 2009, the U.S. is the only nation that compensates nuclear test victims. Since the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act of 1990, more than $1.38 billion in compensation has been approved. The money is going to people who took part in the tests, notably at the Nevada Test Site, and to others exposed to the radiation.[29][30]

Nuclear labor issues

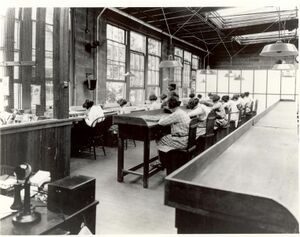

Nuclear labor issues exist within the nuclear power industry and the nuclear weapons production sector that impact upon the lives and health of laborers, itinerant workers and their families.[31][32][33] This subculture of frequently undocumented workers (e.g., Radium Girls, the Fukushima 50, Liquidators, and Nuclear Samurai) do the dirty, difficult, and potentially dangerous work shunned by regular employees.[34] When they exceed their allowable radiation exposure limit at a specific facility, they often migrate to a different nuclear facility. The industry implicitly accepts this conduct as it can not operate without these practices.[35][36]

Existent labor laws protecting worker's health rights are not properly enforced.[37] Records are required to be kept, but frequently they are not. Some personnel were not properly trained resulting in their own exposure to toxic amounts of radiation. At several facilities there are ongoing failures to perform required radiological screenings or to implement corrective actions.

Many questions regarding these nuclear worker conditions go unanswered, and with the exception of a few whistleblowers, the vast majority of laborers – unseen, underpaid, overworked and exploited, have few incentives to share their stories.[38] The median annual wage for hazardous radioactive materials removal workers, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics is $37,590 in the U.S – $18 per hour.[39] A 15-country collaborative cohort study of cancer risks due to exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation, involving 407,391 nuclear industry workers, showed significant increase in cancer mortality. The study evaluated 31 types of cancers, primary and secondary.[40]

الحريات المدنية

Nuclear power is a potential target for terrorists, such as ISIL, and also increases the chances of nuclear weapons proliferation.[41] Circumventing those problems involves reducing civil liberties, such as freedom of speech and of assembly, and so social scientist Brian Martin says that "nuclear power is not a suitable power source for a free society".[42]

Human radiation experiments

The Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments (ACHRE) was formed on January 15, 1994, by President Bill Clinton. Hazel O'Leary, the Secretary of Energy at the U.S. Department of Energy called for a policy of "new openness", initiating the release of over 1.6 million pages of classified documents. These records revealed that since the 1940s, the Atomic Energy Commission was conducting widespread testing on human beings without their consent. Children, pregnant women, as well as male prisoners were injected with or orally consumed radioactive materials.[43]

المراجع

- ^ Doyle, II, Thomas E. (2010). "Reviving Nuclear Ethics: A Renewed Research Agenda for the Twenty-first Century". Ethics and International Affairs. 24 (3): 287–308.

- ^ Nye, Jr., Joseph (1986). Nuclear Ethics. New York, NY: The Free Press. ISBN 0-02-923091-8.

- ^ Sohail H. Hashmi and Steven P. Lee, ed. (2004). Ethics and Weapons of Mass Destruction: Religious and Secular Perspectives. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54526-9.

- ^ Buzan, Barry (2009). "4". The Evolution of International Security Studies. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69422-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Szasz, Paul C. (2004). "2". In Sohail H. Hashmi and Steven P. Lee (ed.). Ethics and Weapons of Mass Destruction: Religious and Secular Perspectives. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–72.

- ^ Doyle, II, Thomas E. (2010). "Kantian nonideal theory and nuclear proliferation". International Theory. 2 (1): 87–112.

- ^ Nye, Jr., Joseph S (1986). "5". Nuclear Ethics. New York NY: The Free Press. pp. 59–80.

- ^ Kavka, Greg S. (1978). "Some Paradoxes of Deterrence". Journal of Philosophy. 75 (6): 285–302.

- ^ Shue, Henry (2004). "7". Ethics and Weapons of Mass Destruction: Religious and Secular Perspectives. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 139–162.

- ^ "Sunday Dialogue: Nuclear Energy, Pro and Con". The New York Times. February 25, 2012.

- ^ Robert Benford. The Anti-nuclear Movement (book review) American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 89, No. 6, (May 1984), pp. 1456–1458.

- ^ James J. MacKenzie. Review of The Nuclear Power Controversy by Arthur W. Murphy The Quarterly Review of Biology, Vol. 52, No. 4 (Dec., 1977), pp. 467–468.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Accident Revealed After 29 Years: H-Bomb Fell Near Albuquerque in 1957". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. August 27, 1986. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ Barry Schneider (May 1975). "Big Bangs from Little Bombs". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. p. 28. Retrieved 2009-07-13.

- ^ James C. Oskins, Michael H. Maggelet (2008). Broken Arrow – The Declassified History of U.S. Nuclear Weapons Accidents. lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-4357-0361-2. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ^ "Ticonderoga Cruise Reports" (Navy.mil weblist of Aug 2003 compilation from cruise reports). Retrieved 2012-04-20.

The National Archives hold[s] deck logs for aircraft carriers for the Vietnam Conflict.

- ^ Broken Arrows at www.atomicarchive.com. Accessed Aug 24, 2007.

- ^ "U.S. Confirms '65 Loss of H-Bomb Near Japanese Islands". The Washington Post. Reuters. May 9, 1989. p. A–27.

- ^ Hayes, Ron (January 17, 2007). "H-bomb incident crippled pilot's career". Palm Beach Post. Archived from the original on 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2006-05-24.

- ^ Maydew, Randall C. (1997). America's Lost H-Bomb: Palomares, Spain, 1966. Sunflower University Press. ISBN 978-0-89745-214-4.

- ^ Long, Tony (January 17, 2008). "Jan. 17, 1966: H-Bombs Rain Down on a Spanish Fishing Village". WIRED. Retrieved 2008-02-16.

- ^ Schlosser, Eric (2013). Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-227-8.

- ^ Christ, Mark K. "Titan II Missile Explosion". The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ Stumpf, David K. (2000). Christ, Mark K.; Slater, Cathryn H. (eds.). "We Can Neither Confirm Nor Deny" Sentinels of History: Refelections on Arkansas Properties on the National Register of Historic Places. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press.

- ^ أ ب Wolfgang Rudig (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman, pp. 54–55.

- ^ "Report on the Health Consequences to the American Population from Nuclear Weapons Tests Conducted by the United States and Other Nations". CDC. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ Council, National Research (11 February 2003). Exposure of the American Population to Radioactive Fallout from Nuclear Weapons Tests: A Review of the CDC-NCI Draft Report on a Feasibility Study of the Health Consequences to the American Population from Nuclear Weapons Tests Conducted by the United States and Other Nations. doi:10.17226/10621. ISBN 978-0-309-08713-1. PMID 25057651 – via www.nap.edu.

- ^ "International". ABC News.

- ^ "Radiation Exposure Compensation System: Claims to Date Summary of Claims Received by 06/11/2009" (PDF).

- ^ Efron, Sonni (December 30, 1999). "System of Disposable Laborers". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Wald, Matthew L. (January 29, 2000). "U.S. Acknowledges Radiation Killed Weapons Workers". New York Times. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Iwaki, H.T. (October 8, 2012). "Meet the Fukushima 50? No, you can't". The Economist. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Bagne, Paul (November 1982). "The Glow Boys: How Desperate Workers are Mopping Up America's Nuclear Mess". Mother Jones. VII (IX): 24–27. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Efron, Sonny (1999-12-30). "System of Disposable Laborers". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Petersen-Smith, Khury. "Twenty-first century colonialism in the Pacific". IRS. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Jacob, P.; Rühm, L.; Blettner, M.; Hammer, G.; Zeeb, H. (March 30, 2009). "Is cancer risk of radiation workers larger than expected?". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 66 (12): 789–796. doi:10.1136/oem.2008.043265. PMC 2776242. PMID 19570756.

- ^ Krolicki, Kevin and Chisa Fujioka. "Japan's "throwaway" nuclear workers". Reuters, MMN: Mother Nature Network. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Bureau of Labor Statistics. "Hazardous Materials Removal Workers". Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Cardis, E.; Vrijheid, M.; Blettner, M.; Gilbert, E.; Hakama, M.; Hill, C.; Howe, G.; Kaldor, J.; Muirhead, C.R.; Schubauer-Berigan, M.; Yoshimura, T.; Bermann, F.; Cowper, G.; Fix, J.; Hacker, C.; Heinmiller, B.; Marshall, M.; Thierry-Chef, I.; Utterback, D.; Ahn, Y-O.; Amoros, E.; Ashmore, P.; Auvinen, A.; Bae, J-M.; Bernar, J.; Biau, A.; Combalot, E.; Deboodt, P.; Sacristan, A. Diez; Eklöf, M.; Engels, H.; Engholm, G.; Gulis, G.; Habib, R.R.; Holan, K.; Hyvonen, H.; Kerekes, A.; Kurtinaitis, J.; Malker, H.; Martuzzi, M.; Mastauskas, A.; Monnet, A.; Moser, M.; Pearce, M.S.; Richardson, D.B.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Rogel, A.; Tardy, H.; Telle-Lamberton, M.; Turai, I.; Usel, M.; Veress, K. (April 2007). "The 15-Country Collaborative Study of Cancer Risk among Radiation Workers in the Nuclear Industry: Estimates of Radiation-Related Cancer Risks". Radiation Research. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 167 (4): 396–416. Bibcode:2007RadR..167..396C. doi:10.1667/RR0553.1. PMID 17388693. S2CID 36282894.

- ^ Sengupta, II, Kim (2016-06-07). "ISIS Nuclear Attack in Europe is a Real Threat". Independent.co.uk.

- ^ Martin, B. (2015). Nuclear power and civil liberties EnergyScience – The Briefing Paper 23 (pp. 1–6) Australia.

- ^ Welsome, Eileen (1999). The Plutonium Files: America's Secret Medical Experiments in the Cold War. New York: Delta Books, Random House, Inc. ISBN 978-0-385-31954-6.