ورل نيلي

| ورل نيلي | |

|---|---|

| |

| بوتسوانا | |

| |

| بحيرة بارينگو، كينيا | |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| أصنوفة غير معروفة (أصلحها): | الفصيلة الورلية (Polydaedalus) |

| Species: | Template:Taxonomy/الفصيلة الورليةا. niloticus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Template:Taxonomy/الفصيلة الورليةالفصيلة niloticus (Linnaeus, 1766)

| |

| |

| النطاق الأصلي للورل النيلي (بما في ذلك الورل النيلي الغرب أفريقي، المعروف غالباً الآن كنوع منفصل) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

ورل نيلي أو ورنه (Nile monitor؛ Varanus niloticus) هو عضو كبير في عائلة الورليات (الفصيلة الورلية) الموجودة في معظم أنحاء أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء وعلى طول النيل، مع وجود تجمعات غازية في أمريكا الشمالية. الورل النيلي معروف للسكان في الغرب الأفريقي في الغابات والساڤانا كنوع منفصل، وهو الورل النيلي الغرب أفريقي (V. stellatus).[2] وهو واحد من أكبر السحالي في العالم ويصل وحتى يتفوق على الورل الأسترالي من حيث الحجم. تشمل الأسماء الشائعة الأخرى السحلية الأفريقية الصغيرة المنقطة،[3] وكذلك الإگوانا والأشكال المختلفة المشتقة منه،[4] مثل گوانا وورل الماء[5]أو ورل النهر (leguan, leguaan, و likkewaan تعني سحلية الورل في الإنگليزية الجنوب أفريقية، ويمكن استبدال تلك الكلمات).[6]وقد أُنشئت مجموعة برية من السحالي، المنحدرة من حيوانات أليفة هربت أو أُطلق سراحها عمداً، في عدة مواقع في فلوريدا.[7]

التبويب

كان نوع الورل النيلي معروف جيدًا بالفعل للأفارقة في العصور القديمة. على سبيل المثال، كان يتم اصطيادها شائعًا على الأرجح كغذاء، في ثقافة جني-جنو منذ ألف عام على الأقل.[8]

تم منح الورل النيلي مرتين الاسم العلمي بواسطة كارولوس لينايوس: أولاً باسم ورل لاسيرتا في عام 1758 في الإصدارة العاشرة من سلسلة نظام الطبيعة، الذي كان نقطة البداية لـعلم تسمية الحيوان . وصفها مرة أخرى في عام 1766 باسم "Lacerta nilotica". على الرغم من كونه أقدم، فإن الاسم المقترح عام 1758 غير صالح لأنه كان مرفوض في القانون الدولي للتسمية الحيوانية 540، مما يجعل اسم 1766 صالحًا.[5][9] صيغ جنس "ڤارانوس" (Varanus) في عام 1820 بواسطة بلاسيوس ميريم. بعد ست سنوات نقل ليوبولد فيتزينجر الورل النيلي إلى هذا الجنس باسم "Varanus niloticus"،[10] وهو الاسم العلمي المقبول حاليًا للأنواع.[5]

مجمع أنواع

كما هو محدد تقليديًا، فإن جهاز الورل النيلي مجمع أنواع.[2] تم وصف الورل المنمق ("V. ornatus") وورل غرب إفريقيا ("V. stellatus") بأنهما نوعان في عامي 1802 و 180 بواسطة فرانسوا ماري داودين. في عام 1942، نقلهما روبرت ميرتنز إلى الورل النيلي ("V. niloticus")؛ كـمرادفات أو نوع فرعي صحيح.[11] كان هذا هو العلاج القياسي حتى عام 1997، عندما أشارت مراجعة تصنيفية استنادًا إلى اللون والمورفولوجيا إلى أن الورل المنمق مميز وأعاد التحقق من صحته كنوع منفصل عن الغابات المطيرة في غرب ووسط إفريقيا.[12] في عام 2016 ، جاءت مراجعة تستند أساسًا إلى علم الوراثة إلى نتيجة أخرى. وجدوا أن الورل من غابات غرب إفريقيا والسافانا المجاورة مميز ويستحق الاعتراف به كنوع منفصل: ورل غرب أفريقيا النيلي (V. stellatus ).[2] يُقدَّر أنه قد انفصل عن الآخرين في مجمع الورل النيلي منذ حوالي 7.7 مليون سنة، مما يجعله أقدم من الانقسام بين البشر والشمبانزي.[8] على النقيض من ذلك، فإن ذلك الموجود في الغابات المطيرة في وسط إفريقيا يتشابه وراثيًا مع الورلي النيلي. يؤدي هذا بشكل أساسي إلى انقسام الورل المنمق - كما تم تعريفها في عام 1997 - إلى قسمين: الغربي وهو ورل النيل الغرب الإفريقيي والشرقي (الغابات المطيرة في إفريقيا الوسطى) يتم نقله مرة أخرى إلى لينضم الورل النيلي. نظرًا لأن النوع المحلي الورل المنمق موجود في دولة وسط إفريقيا الكاميرون، فإن الاسم العلمي "V. ornatus " يصبع مرادفًا لـ" V. niloticus . الاورال ذا "نمط لوني مزخرف" والأورال ذات "نمط لون النيل" يظهرون في كل من الورل النيلي لغرب إفريقيا والورل النيلي ، مع ظهور "الزخرفة" على أنها أكثر تواترًا في الموائل ذات الغابات الكثيفة.[2]

مع كون ورل نيل غرب إفريقيا نوعًا منفصلًا، هناك فرعان حيويان رئيسان في الورل النيلي: فرع حيوي واسع الانتشار موجود في معظم جنوب إفريقيا أفريقيا الوسطى وشرق إفريقيا، وكذلك محليًا في غرب إفريقيا الساحلية. يشمل الفرع الحيو الآخر مراقبي الساحل (مالي إلى إثيوبيا) والنيل.[2] على الرغم من الاختلافات، تحتفظ قاعدة بيانات الزواحف بكل من الورل المنمق وورل نيل غرب إفريقيا كمرادفات لورل النيل، لكن لاحظ أن هذا التعريف الواسع للأنواع يتضمن مجموعات فرعية مميزة.[5]

وصف

يعتبر الورل النيلي أطول أنواع السحالي في أفريقيا.[13] يينمو الورل النيلي من 120 إلى 220 cm (3 ft 11 in إلى 7 ft 3 in) ليصل 244 cm (8 ft) في بعض الحالات.[14][15] في عينة متوسطة الحجم، يكون طول الخطم إلى الفتحة حوالي 50 cm (1 ft 8 in).[16] في كتلة الجسم، رصد اختلاف البالغين على نطاق واسع، حيث ادعت دراسة واحدة فقط 0.8 إلى 1.7 kg (1.8 إلى 3.7 lb)، بينما أشارت دراسات أخرى إلى أن الأوزان تتراوح من 5.9 إلى 15 kg (13 إلى 33 lb) في الأورال الكبيرة. قد تكون الاختلافات بسبب العمر أو الظروف البيئية.[17][18][19] قد يصل حجم العينات الكبيرة بشكل استثنائي إلى 20 kg (44 lb)، ولكن يزن هذا النوع أقل إلى حد ما في المتوسط من الحجم الأكبر ورل الصخور.[20] They have muscular bodies, strong legs, and powerful jaws. Their teeth are sharp and pointed in juvenile animals and become blunt and peg-like in adults. They also possess sharp claws used for climbing, digging, defense, or tearing at their prey. Like all monitors, they have forked tongues, with highly developed olfactory properties. The Nile monitor has quite striking, but variable, skin patterns, as they are greyish-brown above with greenish-yellow barring on the tail and large, greenish-yellow rosette-like spots on their backs with a blackish tiny spot in the middle. Their throats and undersides are an ochre-yellow to a creamy-yellow, often with faint barring.[20]

Their nostrils are placed high on their snouts, indicating these animals are very well adapted for an aquatic lifestyle. They are also excellent climbers and quick runners on land. Nile monitors feed on a wide variety of prey items, including fish, frogs, toads (even poisonous ones of the genera Breviceps and Sclerophrys[21]), small reptiles and birds, rodents,[22] other small mammals (up to domestic cats[23] and young antelopes [Raphicerus][24]), eggs, invertebrates, and carrion.

Distribution and habitat

Nile monitors are native to Sub-Saharan Africa and along the Nile.[25] They are not found in any of the desert regions of Africa (notably Sahara, Kalahari and much of the Horn of Africa), however, as they thrive around rivers.[26][27] Nile monitors were reported to live in and around the Jordan River, Dead Sea, and wadis of the Judaean Desert in Israel until the late 19th century, though they are now extinct in the region.[28]

Invasive species

In Florida in the United States, established breeding populations of Nile monitors have been known to exist in different parts of the state since at least 1990.[29] Genetic studies have shown that these introduced animals are part of the subpopulation that originates from West Africa, and now often is recognized as its own species, the West African Nile monitor.[8] The vast majority of the established breeding population is in Lee County, particularly in the Cape Coral and surrounding regions, including the nearby barrier islands (Sanibel, Captiva, and North Captiva), Pine Island, Fort Myers, and Punta Rassa. Established populations also exist in adjacent Charlotte County, especially on Gasparilla Island.[27] Other areas in Florida with a sizeable number of Nile monitor sightings include Palm Beach County just southwest of West Palm Beach along State Road 80.[30] In July 2008, a Nile monitor was spotted in Homestead, a small city southwest of Miami.[31] Other sightings have been reported near Hollywood, Naranja, and as far south as Key Largo in the Florida Keys.[30] The potential for the established population of Nile monitors in Lee, Charlotte, and other counties in Florida, to negatively impact indigenous crocodilians, such as American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis), and American crocodiles (Crocodylus acutus), is enormous, given that they normally raid crocodile nests, eat eggs, and prey on small crocodiles in Africa. Anecdotal evidence indicates a high rate of disappearance of domestic pets and feral cats in Cape Coral.[27]

In captivity

Nile monitors are often found in the pet trade despite their highly aggressive demeanor and resistance to taming. Juvenile monitors will tail whip as a defensive measure, and as adults they are capable of inflicting moderate to serious wounds from biting and scratching. Nile monitors require a large cage as juveniles quickly grow when fed a varied diet, and large adults often require custom-built quarters.

"There are few lizards less suited to life in captivity than the Nile monitor. Buffrenil (1992) considered that, when fighting for its life, a Nile monitor was a more dangerous adversary than a crocodile of a similar size. Their care presents particular problems on account of the lizards' enormous size and lively dispositions. Very few of the people who buy brightly-coloured baby Nile monitors can be aware that, within a couple of years, their purchase will have turned into an enormous, ferocious carnivore, quite capable of breaking the family cat's neck with a single snap and swallowing it whole."[32]

References

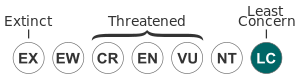

- ^ Wilms, T.; Wagner, P.; Luiselli, L.; Branch, W.R.; Penner, J.; Baha El Din, S.; Beraduccii, J.; Msuya, C.A.; Howell, K.; Ngalason, W. (2021). "Varanus niloticus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T198539A2531945. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T198539A2531945.en. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Dowell, S.A, D.M. Portik, V. de Buffrenil, I Ineich, E Greenbaum, S.O. Kolokotronis and E.R. Hekkala. 2016. Molecular data from contemporary and historical collections reveal a complex story of cryptic diversification in the Varanus (Polydaedalus) niloticus Species Group. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 94(Part B): 591-604. DOI:10.1016/j.ympev.2015.10.004

- ^ "Synonyms of Nile Monitor (Veranus niloticus)". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ قالب:OED

- ^ أ ب ت ث قالب:NRDB species

- ^ "leguan - definition". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ "Nile Monitor". Florida Fish And Wildlife Conservation Commission (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ أ ب ت Yong, Ed (20 April 2016). Florida’s Dragon Problem. The Atlantic. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ ICZN (1959). Opinion 540. Protection under the plenary power of the specific names bengalensis Daudin, 1802, as published in the combination Tupinambis bengalensis, and salvator Laurenti 1768, as published in the combination Stellio salvator. Opin. Declar. intern. Com. zool. Nom. 20: 77-85.

- ^ Fitzinger, L. (1826). Neue Classification der Reptilien nach ihren natürlichen Verwandtschaften nebst einer Verwandschafts-Tafel und einem Verzeichnisse der Reptilien-Sammlung des K. K. Zoologischen Museums zu Wien. Wien.

- ^ Mertens, R. (1942). Die Familie der Warane (Varanidae), 1. Teil: Allgemeines. Abh. Senckenb. naturf. Ges. 462: 1-116.

- ^ Böhme, W., and T. Ziegler (1997). A taxonomic review of the Varanus (Polydaedalus) niloticus (Linnaeus, 1766) species complex. The Herpetological Journal 7: 155-162.

- ^ "5 Fascinating Facts About the Nile Monitor – SafariBookings".

- ^ Nile Monitor Care Sheet

- ^ Enge, K. M., Krysko, K. L., Hankins, K. R., Campbell, T. S., & King, F. W. (2004). Status of the Nile monitor (Varanus niloticus) in southwestern Florida. Southeastern Naturalist, 3(4), 571-582.

- ^ "Varanus niloticus". Monitor Lizards – Captive Husbandry. Monitor-Lizards.net. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ Condon, K. (1987). A kinematic analysis of mesokinesis in the Nile monitor (Varanus niloticus). Experimental biology, 47(2), 73.

- ^ Hirth & Latif 1979

- ^ "ANIMALS - Varanus niloticus". Dr. Giuseppe Mazza's Photomazza. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- ^ أ ب "Nile Monitors". L. Campbell's Herp Page. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- ^ Dalhuijsen,Kim et al:"A comparative analysis of the diets of Varanus albigularis and Varanus niloticus in South Africa. African Zoology 49(1): 83–93 (April 2014)

- ^ "Varanus niloticus (Nile Monitor, Water Leguaan)".

- ^ Daniel Bennett, Brian Basuglo (1999-04-01). University of Aberdeen Black Volta Expedition 1997 Final Report. Viper Press. p. 138. ISBN 9780952663232.

- ^ François Odendaal, Claudio Velásquez Rojas (2007-01-01). Richtersveld: The Land and Its People. Struik. p. 176. ISBN 9781770073418.

- ^ (Schleich et al., 1996; Spawls et al., 2002).

- ^ Reptile Specialists (Nile monitor)

- ^ أ ب ت "NAS - Invasive Species FactSheet: Varanus niloticus (Nile monitor)". Nonindenous Aquatic Species. USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database. Gainesville, FL: United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2009-05-09.

- ^ Baker., Tristram, Henry (2013). The Fauna and Flora of Palestine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 148. ISBN 9781108042048. OCLC 889948524.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ (Campbell, 2003; Enge et al. 2004).

- ^ أ ب "Everglades CISMA". Archived from the original on 2012-01-25. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- ^ Hofmeyer, Erik (10 June 2008). "Homestead ARB home to diverse array of wildlife". Homestead Air Reserve Base News. Homestead Air Reserve Base. Archived from the original on 17 May 2009. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ Bennett, Daniel (1998). Monitor Lizards: Natural History, Biology & Husbandry. Edition Chimaira. ISBN 3-930612-10-0.