ليئة

ليئةإنگليزية: Leah؛ [أ] ( /ˈleɪ.ə/؛ /ˈliːə/)، بحسب التوراة، هي إحدى زوجتي النبي يعقوب. كانت ليئة أولى زوجات يعقوب، والشقيقة الكبرى لزوجته الثانية (والمفضلة لديه) راحيل. وهي والدة ابنه البكر روبين.

في الكتاب المقدس

نظرة عامة

Leah first appears in the Book of Genesis, in Genesis 29, which describes her as the daughter of Laban and the older sister of Rachel, and is said to not compare to Rachel's physical beauty and that she has tender eyes.[ب] Earlier passages in the Book of Genesis give some background on her father's family, noting that through him, she is the niece of Rebecca, who is the wife of Isaac and the mother of Jacob and Esau, and the granddaughter of Bethuel, and rabbinic literature goes even further, with the Book of Jasher claiming Leah and Rachel were twins and recording her mother's name as Adinah and her brothers' names as Beor, Alub, and Murash. Rabbinical literature contradicts itself on whether or not Leah and Rachel were half-siblings to Zilpah and Bilhah, two sisters who would serve as mistresses to Leah's future husband, Jacob, and whose children she and Rachel would raise as their own, as one source[which?] lists them as being daughters of Laban, but not his wife Adinah, and another lists them as being the daughters of Rotheus, a man who was close to Laban but not related to him. If Zilpah and Bilhah were indeed half-sisters of Leah, this would make Leah's adoptive sons, Gad and Asher, and Rachel's adoptive sons, Dan and Naphtali, her nephews. According to Genesis 28:2,[5] the family resided in Paddan Aram, an area believed to correspond with the historical Upper Mesopotamia.[6]

Prior to her and Rachel's mentioning, the Book of Genesis details how their first cousin and future husband, Jacob, with the help of his mother, Rebecca, willfully deceives his dying father, Isaac, into giving him his twin brother Esau's birthright. Fearful of his brother's wrath, Jacob flees his homeland for Haran, where he meets his maternal family, including Laban and his daughters. Biblical passages are dismissive of Leah and favorable of Rachel, with Rachel said to be beautiful and of Leah, only that she had "weary", "tired" or "tender" eyes.[ب] Jacob is eager to marry Rachel and agrees to provide seven years' labor to her father if he can marry her. Laban initially agrees but, on the night of what would've been Jacob and Rachel's wedding, Laban reneges; he insists Jacob marry Leah instead, as she is older. Jacob is ultimately allowed to marry Rachel, which he does immediately after the festivities related to his wedding to Leah end, in exchange for another seven years' labor.

Leah's life as Jacob's wife was distressful. So lonely was she that even the Lord took notice of it and blessed her with many children as consolation. Due to the extreme emotional distress suffered by both Leah (and Rachel) during the marriage, Yahweh later strictly clarified his opposition to uncovering the nakedness of a woman and her sister while both were still living (Genesis 30:1, Leviticus 18:18).

Despite Rachel's infertility, Jacob still favored Rachel over her. He also favored Rachel's sons, Joseph and Benjamin, over Leah's, and made no attempts to hide that from her or his other children. According to 1 Chronicles 5:1,[7] Jacob took the firstborn's birthright, which entitles a firstborn to a larger inheritance in Jewish law, from Reuben, his oldest son, to Joseph, who was his second-youngest son, and, in Genesis 33:2,[8] when he is confronted by Esau, puts Leah, along with Zilpah and Bilhah and all of their sons, in front of himself, Rachel, and Joseph, to be used as something of a buffer or a shield to protect himself in the event the confrontation turned violent. Even after Rachel's death, Leah's situation did not improve, as Jacob took Bilhah, Rachel's handmaiden, as his primary partner.

وصفها

The Torah introduces Leah by describing her with the phrase, "Leah had tender eyes" (Biblical Hebrew: ועיני לאה רכות) (Genesis 29:17).[9] It is argued as to whether the adjective "tender" (רכות) should be taken to mean "delicate and soft" or "weary".[10]

The commentary of Rashi cites a Rabbinic interpretation of how Leah's eyes became weak. According to this story, Leah was destined to marry Jacob's older twin brother, Esau. In the Rabbinic mind, the two brothers are polar opposites; Jacob being a God-fearing scholar and Esau being a hunter who also indulges in idolatry and adultery. But people were saying, "Laban has two daughters and his sister, Rebekah, has two sons. The older daughter (Leah) will marry the older son (Esau), and the younger daughter (Rachel) will marry the younger son (Jacob)."[11] Hearing this, Leah spent most of her time weeping and praying to God to change her destined mate. Thus the Torah describes her eyes as "soft" from weeping. God hearkens to Leah's tears and prayers and allows her to marry Jacob even before Rachel does.

زواجها من يعقوب

Leah becomes Jacob's wife through a deception on the part of her father, Laban. In the Biblical account, Jacob is dispatched to the hometown of Laban — the brother of his mother Rebekah — to avoid being killed by his brother Esau, and to find a wife. Out by the well, he encounters Laban's younger daughter Rachel tending her father's sheep, and decides to marry her. Laban is willing to give Rachel's hand to Jacob as long as he works seven years for her.

On the wedding night, however, Laban switches Leah for Rachel. Later Laban claims that it is uncustomary to give the younger daughter away in marriage before the older one (Genesis 29:16–30).[12] Laban offers to give Rachel to Jacob in marriage in return for another seven years of work (Genesis 29:27).[13] Jacob accepts the offer and marries Rachel after the week-long celebration of his marriage to Leah.

إنجابها

Leah was the mother of six of Jacob's sons, including his first four (Reuben, Simeon, Levi, and Judah), and later two more (Issachar and Zebulun), and a daughter (Dinah). According to the scriptures, God saw that Leah was "unloved" and opened her womb as consolation. Through her sons Levi and Judah, she is thus the matriarch of both the priestly (Levite) and royal (Judahite) tribes in Israel.

Seeing that she was unable to conceive, Rachel offered her handmaid Bilhah to Jacob, and named and raised the two sons (Dan and Naphtali) that Bilhah gave birth to. Leah responded by offering her handmaid Zilpah to Jacob, and named and raised the two sons (Gad and Asher) that Zilpah gave birth to. According to some commentaries, Bilhah and Zilpah are actually half-sisters of Leah and Rachel.[14]

One day, Leah's firstborn son Reuben returned from the field with mandrakes for his mother. Leah had not conceived for a while, and the plant, whose roots resemble the human body, was thought to be an aid to fertility.[15] Frustrated that she was not able to conceive at all, Rachel offered to trade her night with their husband with Leah in return for the mandrakes. Leah agreed, and that night she slept with Jacob and conceived Issachar. Afterwards she gave birth to Zebulun and to a daughter, Dinah.[16] After that, God remembered Rachel and gave her two sons, Joseph and Benjamin.

تنافسها مع راحيل

On a homiletical level, the classic Chassidic texts explain the sisters' rivalry as more than marital jealousy. Each woman desired to grow spiritually in her avodat HaShem (service of God), and therefore sought closeness to the tzadik (Jacob) who is God's personal emissary in this world. By marrying Jacob and bearing his sons, who would be raised in the tzadik's home and continue his mission into the next generation (indeed, all 12 sons became tzadikim in their own right and formed the foundation of the Nation of Israel), they would develop an even closer relationship to God. Therefore, Leah and Rachel each wanted to have as many of those sons as possible, going so far as to offer their handmaids as proxies to Jacob so they could have a share in the upbringing of their handmaids' sons, too.[17]

Each woman also continually questioned whether she was doing enough in her personal efforts toward increased spirituality, and would use the other's example to spur herself on. Rachel envied Leah's tearful prayers, by which she merited to marry the tzaddik and bear six of his twelve sons.[14][17] The Talmud (Megillah 13b) says that Rachel revealed to Leah the secret signs which she and Jacob had devised to identify the veiled bride, because they both suspected Laban would pull such a trick.[18]

وفاتها ودفنها

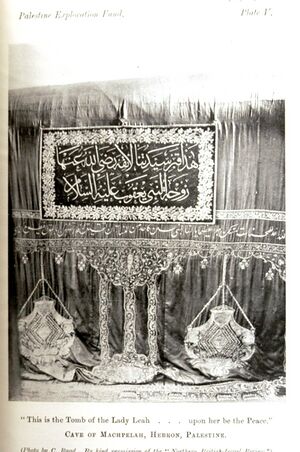

Leah died some time before Jacob (according to Genesis 49:31).[19] She is thought to be buried in the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron alongside Jacob. This cave also houses the graves of Abraham and Sarah, and Isaac and Rebekah.[20]

الرمزية المسيحية في العصور الوسطى

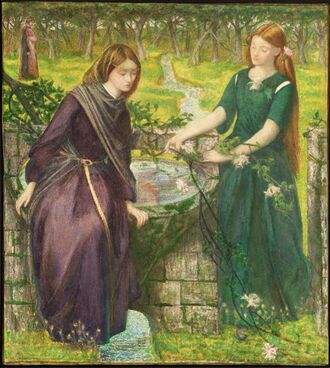

In medieval Christian symbolism, Rachel was taken as a symbol of the contemplative (monastic) Christian life, and Leah as a symbol of the active (non-monastic) life.[21] Dante Alighieri's Purgatorio includes a dream of Rachel and Leah, which inspired illustrations by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and others:

"... in my dream, I seemed to see a woman

both young and fair; along a plain she gathered

flowers, and even as she sang, she said:

Whoever asks my name, know that I'm Leah,

and I apply my lovely hands to fashion

a garland of the flowers I have gathered."[22]

الهوامش

- ^ بالعبرية: לֵאָה، بالعبرية المعاصرة Lēʼa بالطبرية Lēʼā، ISO 259-3 Leˀa؛ سريانية: ܠܝܐ La'ya; من 𒀖 littu Akkadian (Akkadian for 'cow')[1][2][3]

- ^ أ ب "Leah had tender eyes" (Biblical Hebrew: ועיני לאה רכות) (Genesis 29:17).[4] It is debated as to whether the adjective "tender" (רכות) should be taken to mean "delicate and soft" or "weary". Some translations say that it may have meant blue or light colored eyes. Some say that Leah spent most of her time weeping and praying to God to change her destined mate; thus the Torah describes her eyes as "soft" from weeping. See the section #Appearance for further reading.

المصادر

- ^ Meyers, Carol L.; Craven, Toni; Kraemer, Ross Shepard, eds. (2001), Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament, Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, p. 108, ISBN 9780802849625

- ^ Hepner, Gershon (2010), Legal Friction: Law, Narrative, and Identity Politics in Biblical Israel, Bern: Peter Lang, p. 422, ISBN 9780820474625

- ^ ab [COW], Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, OCLC 163207721, http://psd.museum.upenn.edu/epsd/e49.html

- ^ Genesis 29:17 HE

- ^ Genesis 28:2 HE

- ^ "Paddan-Aram". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- ^ Chronicles%205:1&verse=HE&src=! 1 Chronicles 5:1 HE

- ^ Genesis 33:2 HE

- ^ Genesis 29:17 HE

- ^ Bivin, David, "Leah's Tender Eyes," at jerusalemperspective.com Archived 2007-05-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "What's in A Name," Vayetzei (Genesis 28:10-32:3) at aish.com

- ^ Genesis 29:16–30 HE

- ^ Genesis 29:27 HE

- ^ أ ب Ginzberg, Louis (1909) The Legends of the Jews, Volume I, Chapter VI: Jacob, at sacred-texts.com

- ^ Mandrake Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine in the American Bible Society Online Bible Dictionary, 1865, Broadway, New York, NY 10023-7505 at www.bibles.com

- ^ Alihassan, N. (2017). Prophets in Islam. Notion Press. ISBN 9781946822680.

- ^ أ ب Feinhandler, Yisrael Pesach, Beloved Companions, Vayetze - III, "Jealousy Can Be a Tool for Spiritual Growth," at shemayisrael.com

- ^ Wagensberg, Abba (2006), "Between The Lines," in Toras Aish, Volume XIV, No. 11, 2006 Rabbi A. Wagensberg & aish.com

- ^ Genesis 49:31 HE

- ^ Richman, Chaim (1995), "Focus on Hebron," Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine 1995 Light to the Nations, Rabbi Chaim Richman - All Rights Reserved, Reprinted from The Restoration newsletter, July, 1995 (Tammuz/Av, 5755) at lttn.org

- ^ Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory (translation of Dante's Purgatorio), notes on Canto XXVII.

- ^ Dante's Purgatorio, Canto XXVII, lines 97–102, Mandelbaum translation.

وصلات خارجية

The Wiktionary definition of Leah

The Wiktionary definition of Leah Media related to ليئة at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to ليئة at Wikimedia Commons

- Articles containing سريانية-language text

- Articles containing Akkadian-language text

- Articles containing Biblical Hebrew-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- All articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from October 2022

- أنبياء التوراة

- نساء القرن 19 ق.م.

- أشخاص في القرن 19 ق.م.

- أمهات الكتاب المقدس

- أشخاص في سفر التكوين

- أسماء عبرية

- يعقوب

- نساء في الكتاب المقدس