الفنون القتالية الصينية

| الفنون القتالية الصينية | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| الصينية التقليدية | 武術 | ||

| الصينية المبسطة | 武术 | ||

| المعنى الحرفي | " الفنون القتالية" | ||

| |||

الفنون القتالية الصينية أو الكونگ فو /ˈkʌŋ ˈfuː/; Chinese: 功夫; pinyin: gōngfu; Cantonese Yale: gūng fū)، أو كوشو (國術; guóshù) أو وشو (武術; wǔshù)، وهي كلها أساليها قتال متنوعة تطورت على مر العصور في الصين العظمى. غالبًا ما يتم تصنيف أساليب القتال هذه وفقًا للسمات المشتركة، والتي تُعرف باسم "عائلات" فنون الدفاع عن النفس. من أمثلة هذه السمات تمارين شاولينقوان البدنية (少林拳) وتتضمن محاكاة حيوانات أخرى (五形) أو أساليب تدريب مستوحاة من الفلسفات الصينية القديمة والأديان والأساطير. تركز الأساليب الداخلية (内家拳; nèijiāquán) على التلاعب بتشي، أما الأساليب التي تركز على تحسين لياقة العضلات والقلب والأوعية الدموية تسمى الأساليب الخارجية (外家拳؛ wàijiāquán). الرابطة الجغرافية، مثل الموجودة في الشمالية (北拳؛ běiquán) الجنوبية (南拳؛ nánquán) هي طريقة تصنيف شائعة أخرى.

الاسم

كونگ فو ووشو هما لفظان دخيلان مأخوذان من الكَنْتُونية والصينية الفصحى، يشيران إلى الفنون القتالية الصينية. برغم ذلك فان كلمتي كونگ فو ووشو الصينيتين (listen (Mandarin) ; Cantonese Yale: móuh seuht)؛ لهما معنيان مختلفان.[1] حيث أن مقابل "الفنون القتالية الصينية" هو ژونگگو (Chinese: 中國武術; pinyin: zhōngguó wǔshù) (الصينية الفصحى).

في اللغة الصينية، يشير مصطلح كونگ فو إلى أي مهارة يتم اكتسابها من خلال التعلم أو الممارسة. إنها كلمة مركبة تتكون من الكلمات 功 (gōng) التي تعني "العمل"، "الإنجاز"، أو "الجدارة"، و 夫 (fū) وهي جزء أو لاحقة اسمية لها معاني متنوعة.

تعني وشو حرفيًا "الفنون القتالية". وتتكون من المقطعين الصينيين 武術: 武 (wǔ) واللذان يعنيان "قتالي" أو "عسكري" و術 or 术 (shù) والذي ترجم إلى "فن" أو "نظام" أو "مهارة" أو "طريقة". أصبح مصطلح وشو أيضًا اسمًا للرياضة الحديثة وهي عبارة عن معرض ورياضة اتصال كامل بأشكال الأسلحة والأسلحة (套路)، تم تكييفها والحكم عليها وفقًا لمجموعة من المعايير الجمالية للنقاط التي تم تطويرها منذ عام 1949 في الصين.[2][3]

قوانتا (拳法) هو مصطلح صيني آخر لفنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية. تعني "طريقة القبضة" أو "قانون القبضة" ("" quán "تعني"الملاكمة" أو"القبضة"، و" fǎ "تعني" القانون "أو" الطريقة "أو"الطريقة")، على الرغم من كمصطلح مركب فإنه يترجم عادة إلى "الملاكمة" أو "أسلوب القتال". يتم تمثيل فن القتال الياباني كمپو بنفس المقاطع الصينية.

التاريخ

يُعزى نشأة فنون القتال الصينية إلى الحاجة إلى الدفاع عن النفس وتقنيات الصيد والتدريب العسكري في الصين القديمة. كانت ممارسة القتال اليدوي والسلاح مهمة في تدريب الجنود الصينيين القدماء.[4][5]

أصبحت المعرفة التفصيلية عن حالة وتطور فنون القتال الصينية متاحة من عقد نانجينگ (1928-1937)، حيث بذل معهد گوشو المركزي الذي أنشأه نظام كومنتانگ جهدًا لتجميع مسح موسوعي لمدارس فنون الدفاع عن النفس. منذ الخمسينيات من القرن الماضي، نظمت جمهورية الصين الشعبية فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية كمعرض ورياضة اتصال كامل تحت عنوان "وشو".

أصول أسطورية

وفقًا للأسطورة، نشأت فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية خلال فترة أسرة شيا (夏朝) شبه الأسطورية قبل أكثر من 4000 عام.[6] < يقال إن الإمبراطور الأصفر (هوانگدي) (التاريخ الأسطوري للصعود 2698 قبل الميلاد) أدخل أنظمة القتال الأولى إلى الصين.[7] يوصف الإمبراطور الأصفر بأنه جنرال مشهور كتب، قبل أن يصبح زعيمًا للصين، أطروحات مطولة في الطب وعلم التنجيم وفنون الدفاع عن النفس. كان أحد خصومه الرئيسيين هو تشي و (蚩尤) الذي كان يُنسب إليه الفضل باعتباره مبتكر جياو دي، رائد الفن الحديث للمصارعة الصينية.[8]

التاريخ المبكر

تم العثور على أقدم الأدلة التي تشير إلى فنون القتال الصينية في حوليات الربيع والخريف (القرن الخامس قبل الميلاد)،[9] حيث ذكر خلالها نظرية القتال اليدوي، وهي نظرية تدمج مفاهيم تقنيات "القاسية" و"اللينة".[10] تم ذكر نظام المصارعة وكان يسمى juélì (جولي) أو "jiǎolì (角力) (جياولي) في كتاب المناسك.[11] تضمن نظام القتال هذا تقنيات مثل ضربات، ورميات، والتلاعب المشترك، وهجمات نقطة ضغط. أصبحت جياو دي رياضة في عهد أسرة تشين (221-207 قبل الميلاد). سجل "ببليوگرافيات تاريخ هان" أنه، بحلول عهد أسرة هان (206 ق.م. - 8 م)، كان هناك تمييز بين القتال بدون أسلحة بدون قيود، والذي يطلق عليه اسم shǒubó (手搏) أي قتال اليد، والتي تم بالفعل كتابة كتيبات التدريب لها، والمصارعة الرياضية، التي كانت تُعرف باسم juélì (角力). تم توثيق المصارعة أيضًا في Shǐ Jì، سجلات المؤرخ الكبير ، كتبها سيما چيان (حوالي 100 قبل الميلاد).[12]

في أسرة تانگ، تم تخليد أوصاف رقصات السيف في قصائد لي باي. في سونگ وسلالات يوان، رعت المحاكم الإمبراطورية مسابقات شيانگپو. تم تطوير المفاهيم الحديثة للوشو بشكل كامل على يد مينگ وتشينگ.[13]

تأثيرات فلسفية

تغيرت الأفكار المرتبطة بفنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية مع تطور المجتمع الصيني واكتسبت بمرور الوقت بعض القواعد الفلسفية: تتعلق المقاطع في ژوانگزي (莊子)، نص طاوي، بعلم النفس وممارسة فنون الدفاع عن النفس. يُعتقد أن مؤلفها المسمى ژوانگزي قد عاش في القرن الرابع قبل الميلاد. ينسب تاو تى تشينگ، غالبًا إلى لاو زي، هو نص طاوي آخر يحتوي على مبادئ تنطبق على فنون الدفاع عن النفس. وفقًا لأحد النصوص الكلاسيكية للكونفوشيوسيى، زو لي (孫子兵法)، كانت الرماية وقيادة العجلة الحربية جزءًا من "الفنون الستة" ((Chinese: 六藝; pinyin: liu yi، بما في ذلك الطقوس، والموسيقى، وفن الخط والرياضيات) لأسرة ژاو (1122–256 قبل الميلاد). كتب فن الحرب (孫子兵法)، كتبها سون تزو (孫子) خلال القرن السادس قبل الميلاد، ويتناول فيه الحرب العسكرية ولكنه يحتوي على أفكار مستخدمة في فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية.

كان ممارسو الداو يمارسون تمرين الداوين (تمارين بدنية مشابهة لتشيكونگ التي كانت أحد أسلاف التاي تشي) منذ 500 قبل الميلاد.[14] في الفترة 39-92 م، تم إدخال "ستة فصول من القتال اليدوي" في هان شو (تاريخ أسرة هان) التي كتبها پان كو. كما قام الطبيب المعروف هوا تو بتأليف "مسرحية الحيوانات الخمسة" - النمر والغزال والقرد والدب والطيور، عام 208 م تقريبًا..[15] أثرت الفلسفة الطاوية ونهجها في الصحة والتمارين الرياضية على فنون القتال الصينية إلى حد ما. يمكن العثور على إشارة مباشرة إلى مفاهيم الطاوية في أنماط مثل الثمانية الخالدون،" التي تستخدم تقنيات القتال المنسوبة إلى خصائص كل خالد.[16]

الأسر الجنوبية والشمالية (420–589 م)

بناء معبد شاولين

في عام 495 م، تم بناء معبد شاولين في جبل سونگ بمقاطعة خنان. كان الراهب الأول الذي بشر بالبوذية هو راهب هندي يدعى بوذايادرا (佛陀跋陀羅; Fótuóbátuóluó)، وكان الصينيون يطلقون عليه باتو (跋陀) هناك سجلات تاريخية تشير إلى أن أول تلاميذ باتو الصينيين، هويگوانگ 慧光) وسنگتشو (僧稠) كان كلاهما يتمتع بمهارات عسكرية استثنائية.[بحاجة لمصدر] For على سبيل المثال، تم توثيق مهارة سينگتشو مع طاقم القصدير في الشريعة البوذية الصينية.[بحاجة لمصدر] بعد بوذابادرا، جاء إلى شاولين راهب هندي أخر[17] يدعى بوذيهارما (菩提達摩; Pútídámó)، وأطلق عليه الصينين اسم دامو (達摩) عام 527 م، كان تلميذه الصيني، هويكي (慧可)، أيضًا خبيرًا في فنون القتال على درجة عالية من التدريب.[بحاجة لمصدر] يُعتقد أن هؤلاء الرهبان الصينيين الثلاثة الأوائل من شاولين، هويگوانگ، وسينگتشو، وهويكي، ربما كانوا رجالًا عسكريين قبل دخول الحياة الرهبانية.[18]

شاولين وفنون الدفاع عن النفس في المعبد

يعتبر أسلوب شاولين في الكونگ فو أحد أوائل فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية المؤسسية.[19] أقدم دليل على مشاركة شاولين في القتال هو شاهدة من 728 م تشهد على مناسبتين: الدفاع عن دير شاولين من قطاع الطرق حوالي 610 م، ودورهم اللاحق في هزيمة وانگ شيشونگ في معركة هولاو عام 621 م. في الفترة من القرن الثامن إلى القرن الخامس عشر، لا توجد وثائق موجودة تقدم دليلًا على مشاركة معبج شاولين في القتال.

يوجد ما لا يقل عن أربعين مصدرًا يعودوا إلى القرنين السادس عشر والسابع عشر يقدموا دلائل على أن رهبان شاولين مارسوا فنون الدفاع عن النفس، وأصبحت تلك الممارسة القتالية عنصرًا لا يتجزأ من الحياة الرهبانية لشاولين. يعود أقرب ظهور للأسطورة التي يتم الاستشهاد بها كثيرًا بشأن مؤسسة بوذيهارما المفترضة لشاولين كونگ فو إلى هذه الفترة.[20] يعود أصل هذه الأسطورة إلى فترة مينگ يجين جينگ أو "تغيير العضلات الكلاسيكي"، وهو نص مكتوب في عام 1624 منسوب إلى بو`يهارما.

تظهر مراجع ممارسة فنون الدفاع عن النفس في شاولين في أنواع أدبية مختلفة من عهد أسرة مينگ: مرثيات رهبان شاولين المحاربين، وكتيبات فنون الدفاع عن النفس، والموسوعات العسكرية، والكتابات التاريخية، وروايات الرحلات، والخيال، والشعر. ومع ذلك، فإن هذه المصادر لا تشير إلى أسلوب محدد نشأ في شاولين.[21] هذه المصادر، على عكس تلك الموجودة في فترة تانگ، يشير إلى أساليب شاولين للقتال المسلح. تتضمن هذه المهارة التي اشتهر بها رهبان شاولين: عصا ("گان" "gwan" الكانتونية). وصف الجنرال تشي جيگوانگ الذي يعود لعهد مينگ تشوان فان في شاولين (Chinese: 少林拳法; Wade–Giles: Shao Lin Ch'üan Fa; lit. 'Shaolin fist technique'; Japanese: Shorin Kempo) وأساليب استخدام العصيان في كتابه جي شياو شين شو (紀效新書)، والذي يمكن ترجمته إلى "تقنيات فعالة لتسجيل الكتب الجديدة". عندما انتشر هذا الكتاب عبر شرق آسيا، كان له تأثير كبير على تطور فنون الدفاع عن النفس في مناطق مثل أوكيناوا [22] وكوريا.[23]

النسخة الإسلامية

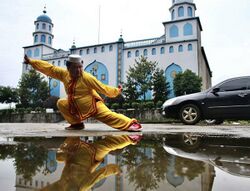

الكونگ فو الإسلامي هو إرث مهم للإسلام في الصين؛ فقد تطور عبر التاريخ على يد معلمين مسلمين، تدربوا على الكمال الجسدي والروحي، ودمجوا تفرد الثقافة الصينية مع الإسلام.

لطالما كانت وسائل الإعلام الغربية مشبعة بصور بروس لي وجاكي شان وجيت لي، لكن ما لا نسمع عنه كثيرًا هو العلاقة بين الإسلام وفنون الدفاع عن النفس.

تراث الصين المسلمة هو إرث الكونگ فو الإسلامي. لقد تدرب المعلمون المسلمون بشكل مستمر وشاق، وغامروا برحلة لا تنتهي نحو الكمال الجسدي والروحي، مستعدين من خلال خدمة إلهام مدى الحياة لمجتمعاتهم المسلمة والصين.

لعبت التجارة المبكرة التي أدت إلى علاقة وثيقة بين المسلمين العرب والصينيين دورًا محوريًا في انتشار الإسلام في الشرق الأقصى بالإضافة إلى ترسيخ الهوية الصينية الإسلامية.

تم توثيق الإسلام في الصين جيدًا حيث يتصرف شعب الهوي كأكبر أقلية مسلمة داخل البلاد. بعد 19 عامًا من وفاة النبي محمد (ص)، بدأت العلاقة بين الصين والجزيرة العربية.

كان الخليفة الثالث عثمان هو الذي بدأ الجهود الواعية الأولى لنشر الإسلام في المنطقة ، كما ساهمت بعثات تجارية لاحقة في انتشار الإسلام.

جاء مسلمو الهوي من هذا النسب، وهو توحيد للجزيرة العربية والصين لتشكيل هذا الموقع الفريد للثقافة الصينية الأصيلة، المشبعة بالتقاليد الإسلامية، والتي لا يزال من الممكن رؤية أمثالها حتى يومنا هذا في أجزاء مختلفة من البلاد.

لم يقتصر الأمر على دمج فنون الدفاع عن النفس مع الجوانب العملية للدفاع في المهام التجارية البحرية الطويلة فحسب، بل كانت أيضًا أداة روحية للعديد من السادة المسلمين. تنعكس الحاجة إلى ضبط النفس وكبحها في كل من فنون الدفاع عن النفس والتعاليم الإسلامية التقليدية.

نجح المسلمون في تنسيق الشكل الداخلي والخارجي للكونگ فو، ونجحوا في البقاء قريبين من عقيدتهم الأصلية، وتطبيق "الاجتهاد" الهائل في إنتاج فنون قتالية فعالة وأصلية خاصة بهم، على أساس دينهم.

تم استخدام مفهوم ضبط النفس الإسلامي من قبل أساتذة فنون الدفاع عن النفس في المجال البدني أيضًا. مع الممارسين الذين يركزون على الجوانب الروحية والجسدية للتدريب.

غالبًا ما تم تلخيص فنون القتال الإسلامية الأصلية بأسماء إسلامية (عربية) مميزة وبلغت فعاليتها الفنية ذروتها داخل دوائر الكونگ فو في الصين

اتقن المسلمون أشكال فنية مختلفة مثل "سيلات" و"وشو" في القرون القليلة الماضية، مع العديد من فنون القتال الأصلية التي تم إنشاؤها أو تكييفها على يد المسلمين أيضًا، مثل ژاقوان وپيگوان.

كانت هذه التطورات الأصلية أدوات تم ابتكارها في كثير من الأحيان على يد مسؤولي الجيش أو لحماية المسلمين في الصين، وتم تناقلها سراً عبر الأجيال عبر المجتمعات الإسلامية.

في تاريخ فنون الدفاع عن النفس والإسلام، هناك العديد من الأسماء التي يجب مراعاتها. تدرب المعلمون بشكل خاص مثل وانگ زيپينگ. (1881-1973) وتشانگ تونگ شنگ (1908-1986) في تخصصهم، مع الاحتفاظ بإيمانهم واستخدامه كوسيلة للاقتراب من الله والإسلام.

كان المعلم وانگ زيپينگ. (1881-1973) ممارسًا صينيًا مسلمًا لفنون القتال الصينية والطب التقليدي. شغل منصب قائد قسم كونگ فو ساولين في معهد الفنون القتالية في عام 1928 وكان أيضًا نائب رئيس جمعية الووشو الصينية

المعلم وانگ زيپينگ المعروف بأنه سيد الووشو، كان أيضًا رجلاً مثقفًا فيما يتعلق بالإسلام. عُرف عنه أنه يرفع الحجارة الثقيلة أثناء تلاوة القرآن.

تحكي قصة شهيرة عن معارضته للقوات الألمانية التي حاولت اقتحام أبواب مسجد چينژو، المدون بتاريخ المسلمين في الصين. لم يسمح السيد وانگ، وتحدى الجنود في مسابقة رفع الأثقال وفاز بعد ذلك!

كان وانگ زيپينگ أستاذًا في مختلف التخصصات الأخرى، وكان مصدر إلهام للناس، المسلمين وغير المسلمين على حد سواء. أتاح له إتقانه لفنون الدفاع عن النفس الفوز على مختلف المعارضين الأجانب، مما أدى إلى اتباع الطلاب ونشر الإسلام بين الشعب الصيني.

كان تشانگ تونگشنگ (1908-1986) فنانًا عسكريًا من هوي. كان أحد أشهر ممارسي ومعلمي المصارعة الصينيين (المعروفين أيضًا باسم شواي جياون). كان تشانگ مسلمًا متدينًا.

أطلق عليه لقب "الفراشة الطائرة" في وقت مبكر من حياته المهنية لقدرته على الدوران وإيقاع خصومه في شرك. كان معلم تشانگ الكبير هو الشهير تشانگ فانگين وهو خبير في پاوتينگ وشوايتشياو أسرع وأقوى الفروع الثلاثة الرئيسية للفن.

في واحدة من أشهر مبارياته، تحدى تشانگ بطل المصارعة المنغولي، هوكلي، الذي كان من المفترض أن يبلغ طوله 7 أقدام ووزنه حوالي 400 رطل. انتصر تشانگ، وألقى هوكلي مرارا وتكرارا، على الرغم من اختلاف الحجم.

التاريخ الحديث

العصر الحديث

وصلت معظم أساليب القتال التي تُمارس كفنون قتالية صينية تقليدية اليوم إلى شعبيتها في القرن العشرين. بعض هذه تشمل باگوازانگ، وملاكمة السكران، ومخلب النسر، والحيوانات الخمس، وشينگي، وهنگ گار، وكونگ فو القردة، باك مي پاي، وفرس النبي الشمالي، وفرس النبي الجنوبي، وفوجيان وايت كرين، وجو جا، ووينگ تشون وتايجيتشوان. الزيادة في شعبية هذه الأنماط هي نتيجة للتغييرات الدراماتيكية التي تحدث داخل المجتمع الصيني.

في عام 1900-1901، انتفضت القبضة الصالحة والمتناغمة ضد المحتلين الأجانب والمبشرين المسيحيين في الصين. تُعرف هذه الانتفاضة في الغرب باسم ثورة الملاكمين بسبب فنون الدفاع عن النفس وتمارين الجمباز التي مارسها المتمردون. سيطرت الإمبراطورة الأرملة تسيشي على التمرد وحاولت استخدامه ضد القوى الأجنبية. أدى فشل التمرد بعد عشر سنوات إلى سقوط أسرة تشينگ وتأسيس جمهورية الصين (1912-1949)|جمهورية الصين]].

تأثر العرض الحالي لفنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية بشدة بأحداث الفترة الجمهورية (1912-1949). في الفترة الانتقالية بين سقوط أسرة تشينگ بالإضافة إلى اضطرابات الغزو الياباني والحرب الأهلية الصينية، أصبحت فنون القتال الصينية في متناول عامة الناس حيث تم تشجيع العديد من ممارسي فنون الدفاع عن النفس على تعليم تلك الفنون بشكل علني. في ذلك الوقت، اعتبر البعض فنون الدفاع عن النفس وسيلة لتعزيز الفخر الوطني وبناء أمة قوية. ونتيجة لذلك، تم نشر العديد من كتيبات التدريب (拳 譜)، وتم إنشاء أكاديمية تدريب، وتم تنظيم اختبارين وطنيين وسافرت فرق العرض إلى الخارج.[24] تم تشكيل العديد من جمعيات فنون الدفاع عن النفس في جميع أنحاء الصين وفي مختلف المجتمعات الصينية في الخارج. تأسست أكاديمية گوشو المركزية (Zhongyang 中央 國 術 館) من قبل الحكومة الوطنية في عام 1928. [25] وجمعية جينگ وو الرياضية (精 武 體育 會) التي أسسها هو يوانجيا في عام 1910 هي أمثلة على المنظمات التي روجت لنهج منهجي للتدريب في فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية.[26][27][28] نظمت الحكومة الجمهورية سلسلة من المسابقات الإقليمية والوطنية بداية من عام 1932 للترويج لفنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية. في عام 1936، في الألعاب الأولمبية الحادية عشرة في برلين، عرضت مجموعة من فناني الدفاع عن النفس الصينيين فنهم أمام جمهور دولي لأول مرة.

تم تقديم المصطلح كوشو (أو "گوشو"، 國術 يعني "الفن القومي")، بدلاً من المصطلح العامي كونگ فو بواسطة الكومينتانگ في محاولة لربط فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية بشكل أوثق مع الكبرياء الوطني بدلاً من الإنجاز الفردي.

الصين الشعبية

شهدت فنون القتال الصينية انتشارًا دوليًا سريعًا مع نهاية الحرب الأهلية الصينية وتأسيس جمهورية الصين الشعبية في 1 أكتوبر 1949. اختار العديد من فناني القتال المشهورين الهروب من حكم جمهورية الصين الشعبية والهجرة إلى تايوان، وهونگ كونگ،[29] وأجزاء أخرى من العالم. بدأ هؤلاء الأساتذة التدريس داخل مجتمعات الصينيون في الخارج لكنهم في النهاية وسعوا تعاليمهم لتشمل أفرادًا من مجموعات عرقية أخرى.

داخل الصين، تم تثبيط ممارسة فنون القتال التقليدية خلال السنوات المضطربة من الثورة الثقافية الصينية (1969-1976).[3] مثل العديد من الجوانب الأخرى للحياة الصينية التقليدية، تعرضت فنون الدفاع عن النفس لتحول جذري على يد جمهورية الصين الشعبية لتتماشى مع العقيدة الثورية الماوية.[3] روجت تنظمها لرياضة الوشو التي تنظمها اللجنة كبديل للمدارس المستقلة لفنون الدفاع عن النفس. تم فصل هذه الرياضة المنافسة الجديدة عما كان يُنظر إليه على أنه جوانب الدفاع عن النفس المحتملة التخريبية وارتباطها بفنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية.[3]

في عام 1958، أنشأت الحكومة جمعية الوشو لعموم الصين كمنظمة جامعة لتنظيم التدريب على فنون الدفاع عن النفس. أخذت لجنة الدولة الصينية للثقافة البدنية والرياضة زمام المبادرة في إنشاء أشكال موحدة لمعظم الفنون الرئيسية. خلال هذه الفترة، تم إنشاء نظام وشو الوطني الذي تضمن النماذج القياسية، والمناهج التعليمية، ودرجات المعلم. تم تقديم الوشو على مستوى المدرسة الثانوية والجامعة. تم تخفيف قمع التدريس التقليدي خلال عصر إعادة الإعمار (1976-1989)، حيث أصبحت الأيديولوجية الشيوعية أكثر ملاءمة لوجهات النظر البديلة.[30] في عام 1979، أنشأت لجنة الدولة للثقافة البدنية والرياضة فريق عمل خاص لإعادة تقييم تعليم وممارسة الوشو. في عام 1986، تم إنشاء المعهد الوطني الصيني لبحوث الوشو كسلطة مركزية للبحث وإدارة أنشطة الوشو في جمهورية الصين الشعبية.[31]

أدى تغيير السياسات والمواقف الحكومية تجاه الرياضة، بشكل عام، إلى إغلاق لجنة الرياضة الحكومية (السلطة الرياضية المركزية) في عام 1998. ويُنظر إلى هذا الإغلاق على أنه محاولة لإلغاء تسييس الرياضة المنظمة جزئيًا وتحريك الصينيين. ودفع السياسات الرياضية نحو نهج سوق مدفوع أكثر.[32] نتيجة لهذه العوامل الاجتماعية المتغيرة داخل الصين، تقوم الحكومة الصينية بالترويج لكل من الأساليب التقليدية ومقاربات الوشو الحديثة .[33]

تعتبر فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية عنصرًا أساسيًا في الثقافة الشعبية الصينية في القرن العشرين.[34] وشيا أو "خيال فنون القتال" هو نوع شعبي ظهر في أوائل القرن العشرين وبلغ ذروته في شعبيته خلال الستينيات والثمانينيات. بدأ إنتاج أفلام وشيا منذ عشرينيات القرن الماضي. قام الكومينتانغ بقمع ووكسيا ، متهمين إياها بالترويج للخرافات والفوضى العنيفة. لهذا السبب ، ازدهرت وشيا في هونگ كونج البريطانية، وأصبح نوع أفلام الكونگ فو في سينما الحركة في الكونگ فو ذائع الصيت، حيث جذب الاهتمام الدولي منذ سبعينيات القرن الماضي. شهد هذا النوع من الأفلام انخفاضًا حادًا في أواخر التسعينيات حيث انهارت صناعة أفلام هونگ كونج بسبب الكساد الاقتصادي.

في أعقاب فيلم إنگ لي النمر الرابض، التنين الخفي (2000)، كان هناك إتجاه لإحياء لأفلام وشيا المنتجة في الصين والتي تستهدف جمهورًا دوليًا، بما في ذلك فيلم ژانگ ييومو البطل (2002)، ومنزل الخناجر المتطايرة (2004) ولعنة الزهرة الذهبية (2006)، وكذلك تشاو-پين وفيلم جون وو عهد القتلة (2010).

الأساليب

تتمتع الصين بتاريخ طويل من تقاليد فنون الدفاع عن النفس التي تشمل مئات الأساليب المختلفة. على مدار الألفي عام الماضية، تم تطوير العديد من الأساليب المميزة ولكل منها مجموعة من الأساليب والأفكار الخاصة بها.[35] هناك أيضًا موضوعات مشتركة للأنماط المختلفة، والتي غالبًا ما يتم تصنيفها حسب "العائلات" (家; jiā)، و"المدارس" (派; pai) أو (門; men). هناك أساليب تحاكي حركات الحيوانات وغيرها تستوحي الإلهام من مختلف الفلسفات الصينية والأساطير والقصص. تضع بعض الأنماط معظم تركيزها في تسخير تشي، بينما يركز البعض الآخر على المنافسة.

يمكن تقسيم فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية إلى فئات مختلفة للتمييز بينها: على سبيل المثال، خارجية (外家拳) والداخلية (內家拳).[36] يمكن أيضًا تصنيف فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية حسب الموقع، كما هو الحال فتنقسم إلى الشمالية (北拳) والجنوبية (南拳) أيضًا، بالإشارة إلى أي جزء من الصين نشأت الأنماط، مفصولة بنهر يانگتسى (長江)؛ قد يتم تصنيف فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية وفقًا لمقاطعة أو مدينتهم.[24] يتمثل الاختلاف الرئيسي الملحوظ بين الأساليب الشمالية والجنوبية في أن الأساليب الشمالية تميل إلى التأكيد على الركلات السريعة والقوية والقفزات العالية والحركة المرنة والسريعة بشكل عام، بينما تركز الأساليب الجنوبية بشكل أكبر على تقنيات الذراع واليد القوية، والمواقف الثابتة والثابتة و حركة سريعة. تتضمن أمثلة الأساليب الشمالية تشانگتشوان وشينگيتشوان من الأمثلة على الأساليب الجنوبية باك مي ووزوكوان وتشوي لي فوت و وينج تشون. يمكن أيضًا تقسيم فنون القتال الصينية وفقًا للدين والأساليب المقلدة (象形拳)، والأنماط العائلية مثل ونگ گار (洪家). هناك اختلافات مميزة في التدريب بين المجموعات المختلفة لفنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية بغض النظر عن نوع التصنيف. ومع ذلك، فإن قلة من الفنانين القتاليين ذوي الخبرة يميزون بشكل واضح بين الأنماط الداخلية والخارجية، أو يشتركون في فكرة أن الأنظمة الشمالية تعتمد في الغالب على الركل وأنظمة الجنوب تعتمد بشكل أكبر على تقنيات الجزء العلوي من الجسم. تحتوي معظم الأنماط على عناصر صلبة وناعمة، بغض النظر عن تسمياتها الداخلية. بتحليل الاختلاف وفقًا لمبادئ يين ويانگ، سيؤكد الفلاسفة أن غياب أي منهما سيجعل مهارات الممارس غير متوازنة أو ناقصة، لأن كل من الين واليانگ وحدهما يمثلان نصف الكل فقط. إذا كانت هذه الاختلافات موجودة من قبل، فقد تم طمسها منذ ذلك الحين.

التدريب

يتكون تدريب فنون القتال الصينية من المكونات التالية: الأساسيات والأشكال والتطبيقات والأسلحة؛ تضع الأنماط المختلفة تركيزًا متفاوتًا على كل مكون.[37] بالإضافة إلى الفلسفة والأخلاق وحتى الممارسة الطبية[38] التي تحظى بتقدير كبير من جانب معظم فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية. يجب أن يوفر نظام التدريب الكامل نظرة ثاقبة للمواقف والثقافة الصينية.[39]

الأساسيات

تعتبر الأساسيات (基本功) جزءًا حيويًا من أي تدريب عسكري، حيث لا يمكن للطالب التقدم إلى المراحل الأكثر تقدمًا بدونها. تتكون الأساسيات عادةً من تقنيات بدائية، وتمارين مشروطة، بما في ذلك موقف (فنون قتالية) مواقف. قد يتضمن التدريب الأساسي حركات بسيطة يتم ممارستها بشكل متكرر؛ ومن الأمثلة الأخرى على التدريب الأساسي: التمدد، والتأمل، والضرب، والرمي، أو القفز. بدون عضلات قوية ومرنة، وإدارة تشي أو التنفس، وميكانيكا الجسم المناسبة، من المستحيل أن يتقدم الطالب في فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية.[40][41] هناك مقولة شائعة تتعلق بالتدريب الأساسي في فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية كما يلي:[42]

内外相合,外重手眼身法步,内修心神意氣力。

والذي يترجم إلى:

تدريب داخلي وخارجي. يشمل التدريب الخارجي اليدين والعينين والجسم والوقوف. يشمل التدريب الداخلي القلب والروح والعقل والتنفس والقوة.

الوضعيات

المواقف (الخطوات أو 步法) هي أوضاع هيكلية مستخدمة في تدريب فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية.[43][44][نشر ذاتي سطري?] تمثل أساس وشكل قاعدة المقاتل. كل نمط له أسماء وأشكال مختلفة لكل وضعية . يمكن التمييز بين المواقف من خلال وضع القدم، وتوزيع الوزن، ومحاذاة الجسم، وما إلى ذلك. يمكن ممارسة تدريب الوقوف بشكل ثابت، والهدف منه هو الحفاظ على هيكل الموقف خلال فترة زمنية محددة، أو ديناميكيًا، وفي هذه الحالة يتم تنفيذ سلسلة من الحركات بشكل متكرر. موقف الحصان ((騎馬步/馬步؛ وموقف القوس) هي أمثلة على الوضعيات الموجودة في العديد من أساليب فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية.

التأمل

في العديد من فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية، يعتبر التأمل عنصرًا مهمًا في التدريب الأساسي. يمكن استخدام التأمل لتطوير التركيز والوضوح العقلي ويمكن أن يكون بمثابة أساس لتدريب تشيگونگ.[45][46]

استخدام تشي

نجد مفهوم تشي أو (氣) في عدد من فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية. يُعرَّف مصطلح "تشي" بشكل مختلف على أنه طاقة داخلية أو "قوة حياة" يُقال عنها أنها تحي الكائنات الحية؛ كمصطلح لمحاذاة الهيكل العظمي والاستخدام الفعال للعضلات (يُعرف أحيانًا باسم فا تجين أو تجين)؛ أو كاختصار لمفاهيم قد لا يكون طالب فنون الدفاع عن النفس جاهزًا لفهمها بالكامل. هذه المعاني ليست بالضرورة متبادلة.[note 1] إن وجود "تشي" كشكل من أشكال الطاقة يمكن قياسه كما نوقش في الطب الصيني التقليدي ليس له أساس في الفهم العلمي للفيزياء أو الطب أو علم الأحياء أو فسيولوجيا الإنسان.[47]

هناك العديد من الأفكار المتعلقة بالتحكم في طاقة تشي إلى الحد الذي يمكن استخدامه لعلاج النفس أو الأخرين.[48] تؤمن بعض الأساليب بتركيز تشي على نقطة واحدة عند مهاجمة مناطق معينة من جسم الإنسان واستهدافها. تُعرف هذه التقنيات باسم ديم ماك ولها مبادئ مشابهة للعلاج بالضغط.[49]

تدريب الأسلحة

تستفيد معظم الأساليب الصينية أيضًا من التدريب في ترسانة واسعة من الأسلحة الصينية لتكييف الجسم بالإضافة إلى التنسيق والإستراتيجية التدريبات.[50] يتم تنفيذ التدريب على الأسلحة (器械؛ تشيشى) بشكل عام بعد أن يصبح الطالب بارعًا في الأشكال الأساسية والتدريب على التطبيقات. النظرية الأساسية للتدريب على الأسلحة هي اعتبار السلاح امتدادًا للجسم. لديها نفس متطلبات الحركة وتنسيق الجسم مثل الأساسيات.[51] تستمر عملية التدريب على الأسلحة باستخدام النماذج والنماذج مع الشركاء ثم التطبيقات. تحتوي معظم الأنظمة على طرق تدريب لكل من ثمانية عشر سلاحًا من الوشو (十八般兵器; shíbābānbīngqì) بالإضافة إلى الأدوات المتخصصة خاصة بالنظام.

التطبيقات

يشير مصطلح "التطبيق" إلى الاستخدام العملي للتقنيات القتالية. تعتمد تقنيات فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية بشكل مثالي على الكفاءة والفعالية.[52][53] يتضمن التطبيق تدريبات غير متوافقة، مثل دفع اليدين في العديد من فنون القتال الداخلية، و السجال، والتي تحدث ضمن مجموعة متنوعة من مستويات الاتصال ومجموعات القواعد.

يختلف وقت وكيفية تدريس التطبيقات من نمط إلى آخر. اليوم، تبدأ العديد من الأساليب في تعليم الطلاب الجدد من خلال التركيز على التمارين التي يعرف فيها كل طالب نطاقًا محددًا من القتال والتقنية للتعمق فيها. غالبًا ما تكون هذه التدريبات شبه متوافقة، مما يعني أن طالبًا واحدًا لا يقدم مقاومة نشطة للتقنية، من أجل السماح بتنفيذها بشكل واضح ونظيف. في التدريبات الأكثر مقاومة ، يتم تطبيق قواعد أقل، ويتدرب الطلاب على كيفية الرد والاستجابة. يشير مصطلح "السجال" إلى تنسيق أكثر تقدمًا يحاكي موقفًا قتاليًا مع تضمين قواعد تقلل من فرصة الإصابة الخطيرة.

تشمل تخصصات السجال التنافسية الصينية سانشو الكيك بوكسينگ (散手)) والصينية المصارعة الشعبية شوايجياو (摔跤)، التي تم التنافس عليها تقليديًا على ساحة منصة مرتفعة، أو ليتاي (擂台).[54] تم استخدام ليتاي في مباريات التحدي العامة التي ظهرت لأول مرة في أسرة سونگ. كان الهدف من تلك المسابقات هو إخراج الخصم من منصة مرتفعة بأي وسيلة ضرورية.

تمثل سان شو التطور الحديث لمسابقات لي تاي، ولكن مع وجود قواعد لتقليل فرصة الإصابة الخطيرة. تقوم العديد من مدارس فنون الدفاع عن النفس الصينية بالتدريس أو العمل ضمن مجموعات قواعد سانشو، وتعمل على دمج الحركات والخصائص ونظرية أسلوبها.[55] يتنافس فنانو الدفاع عن النفس الصينيون أيضًا في رياضة القتال غير الصينية أو المختلطة، بما في ذلك الملاكمة والكيك بوكسينگ و فنون القتال المختلطة.

Forms (taolu)

Forms or taolu (Chinese: 套路; pinyin: tàolù) in Chinese are series of predetermined movements combined so they can be practiced as a continuous set of movements. Forms were originally intended to preserve the lineage of a particular style branch, and were often taught to advanced students selected for that purpose. Forms contained both literal, representative and exercise-oriented forms of applicable techniques that students could extract, test, and train in through sparring sessions.[56]

Today, many consider taolu to be one of the most important practices in Chinese martial arts. Traditionally, they played a smaller role in training for combat application and took a back seat to sparring, drilling, and conditioning. Forms gradually build up a practitioner's flexibility, internal and external strength, speed and stamina, and they teach balance and coordination. Many styles contain forms that use weapons of various lengths and types, using one or two hands. Some styles focus on a certain type of weapon. Forms are meant to be both practical, usable, and applicable as well as to promote fluid motion, meditation, flexibility, balance, and coordination. Students are encouraged to visualize an attacker while training the form.

There are two general types of taolu in Chinese martial arts. Most common are solo forms performed by a single student. There are also sparring forms — choreographed fighting sets performed by two or more people. Sparring forms were designed both to acquaint beginning fighters with basic measures and concepts of combat and to serve as performance pieces for the school. Weapons-based sparring forms are especially useful for teaching students the extension, range, and technique required to manage a weapon.

Forms in Traditional Chinese Martial Arts

The term taolu (套路) is a shortened version of Tao Lu Yun Dong (套路運動), an expression introduced only recently with the popularity of modern wushu. This expression refers to "exercise sets" and used in the context of athletics or sport.

In contrast, in traditional Chinese martial arts alternative terminologies for the training (練) of 'sets or forms are:

- lian quan tao (練拳套) – practicing a sequence of fists.

- lian quan jiao (練拳腳) – practicing fists and feet.

- lian bing qi (練兵器) – practicing weapons.

- dui da (對打) and dui lian (對練) – fighting sets.

Traditional "sparring" sets, called dui da (對打) or dui lian (對練), were an essential part of Chinese martial arts for centuries. Dui lian means, to train by a pair of combatants opposing each other—the character lian (練), refers to practice; to train; to perfect one's skill; to drill. As well, often one of these terms are also included in the name of fighting sets (雙演; shuang yan), "paired practice" (掙勝; zheng sheng), "to struggle with strength for victory" (敵; di), match – the character suggests to strike an enemy; and "to break" (破; po).

Generally, there are 21, 18, 12, 9 or 5 drills or 'exchanges/groupings' of attacks and counterattacks, in each dui lian set. These drills were considered only generic patterns and never meant to be considered inflexible 'tricks'. Students practiced smaller parts/exchanges, individually with opponents switching sides in a continuous flow. Dui lian were not only sophisticated and effective methods of passing on the fighting knowledge of the older generation, but they were also essential and effective training methods. The relationship between single sets and contact sets is complicated, in that some skills cannot be developed with solo 'sets', and, conversely, with dui lian. Unfortunately, it appears that most traditional combat oriented dui lian and their training methodology have disappeared, especially those concerning weapons. There are several reasons for this. In modern Chinese martial arts, most of the dui lian are recent inventions designed for light props resembling weapons, with safety and drama in mind. The role of this kind of training has degenerated to the point of being useless in a practical sense, and, at best, is just performance.

By the early Song period, sets were not so much "individual isolated technique strung together" but rather were composed of techniques and counter technique groupings. It is quite clear that "sets" and "fighting (two-person) sets" have been instrumental in traditional Chinese martial arts for many hundreds of years—even before the Song Dynasty. There are images of two-person weapon training in Chinese stone painting going back at least to the Eastern Han Dynasty.

According to what has been passed on by the older generations, the approximate ratio of contact sets to single sets was approximately 1:3. In other words, about 30% of the 'sets' practiced at Shaolin were contact sets, dui lian, and two-person drill training. This ratio is, in part, evidenced by the Qing Dynasty mural at Shaolin.

For most of its history, Shaolin martial arts was mostly weapon-focused: staves were used to defend the monastery, not bare hands. Even the more recent military exploits of Shaolin during the Ming and Qing Dynasties involved weapons. According to some traditions, monks first studied basics for one year and were then taught staff fighting so that they could protect the monastery. Although wrestling has been as sport in China for centuries, weapons have been an essential part of Chinese wushu since ancient times. If one wants to talk about recent or 'modern' developments in Chinese martial arts (including Shaolin for that matter), it is the over-emphasis on bare hand fighting. During the Northern Song Dynasty (976- 997 A.D) when platform fighting is known as Da Laitai (Title Fights Challenge on Platform) first appeared, these fights were with only swords and staves. Although later, when bare hand fights appeared as well, it was the weapons events that became the most famous. These open-ring competitions had regulations and were organized by government organizations; the public also organized some. The government competitions, held in the capital and prefectures, resulted in appointments for winners, to military posts.

Practice forms vs. kung fu in combat

Even though forms in Chinese martial arts are intended to depict realistic martial techniques, the movements are not always identical to how techniques would be applied in combat. Many forms have been elaborated upon, on the one hand, to provide better combat preparedness, and on the other hand to look more aesthetically pleasing. One manifestation of this tendency toward elaboration beyond combat application is the use of lower stances and higher, stretching kicks. These two maneuvers are unrealistic in combat and are used in forms for exercise purposes.[57] Many modern schools have replaced practical defense or offense movements with acrobatic feats that are more spectacular to watch, thereby gaining favor during exhibitions and competitions.[note 2] This has led to criticisms by traditionalists of the endorsement of the more acrobatic, show-oriented Wushu competition.[58] Historically forms were often performed for entertainment purposes long before the advent of modern Wushu as practitioners have looked for supplementary income by performing on the streets or in theaters. Documentation in ancient literature during the Tang Dynasty (618–907) and the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1279) suggests some sets, (including two + person sets: dui da also called dui lian) became very elaborate and 'flowery', many mainly concerned with aesthetics. During this time, some martial arts systems devolved to the point that they became popular forms of martial art storytelling entertainment shows. This created an entire category of martial arts known as Hua Fa Wuyi. During the Northern Song period, it was noted by historians this type of training had a negative influence on training in the military.

Many traditional Chinese martial artists, as well as practitioners of modern sport combat, have become critical of the perception that forms work is more relevant to the art than sparring and drill application, while most continue to see traditional forms practice within the traditional context—as vital to both proper combat execution, the Shaolin aesthetic as an art form, as well as upholding the meditative function of the physical art form.[59]

Another reason why techniques often appear different in forms when contrasted with sparring application is thought by some to come from the concealment of the actual functions of the techniques from outsiders.[60][نشر ذاتي سطري?]

Forms practice is mostly known for teaching combat techniques yet when practicing forms, the practitioner focuses on posture, breathing, and performing the techniques of both right and left sides of the body.[61]

Wushu

The word wu (武; wǔ) means "martial". Its Chinese character is made of two parts; the first meaning "walk" or "stop" (止; zhǐ) and the second meaning "lance" (戈; gē). This implies that "wu 武" is a defensive use of combat.[محل شك] The term "wushu 武術" meaning "martial arts" goes back as far as the Liang Dynasty (502–557) in an anthology compiled by Xiao Tong (蕭通), (Prince Zhaoming; 昭明太子 d. 531), called Selected Literature (文選; Wénxuǎn). The term is found in the second verse of a poem by Yan Yanzhi titled: 皇太子釋奠會作詩 "Huang Taizi Shidian Hui Zuoshi".

"The great man grows the many myriad things . . .

Breaking away from the military arts,

He promotes fully the cultural mandates."

- (Translation from: Echoes of the Past by Yan Yanzhi (384–456))

The term wushu is also found in a poem by Cheng Shao (1626–1644) from the Ming Dynasty.

The earliest term for 'martial arts' can be found in the Han History (206BC-23AD) was "military fighting techniques" (兵技巧; bīng jìqiǎo). During the Song period (c.960) the name changed to "martial arts" (武藝; wǔyì). In 1928 the name was changed to "national arts" (國術; guóshù) when the National Martial Arts Academy was established in Nanjing. The term reverted to wǔshù under the People's Republic of China during the early 1950s.

As forms have grown in complexity and quantity over the years, and many forms alone could be practiced for a lifetime, modern styles of Chinese martial arts have developed that concentrate solely on forms, and do not practice application at all. These styles are primarily aimed at exhibition and competition, and often include more acrobatic jumps and movements added for enhanced visual effect[62] compared to the traditional styles. Those who generally prefer to practice traditional styles, focused less on exhibition, are often referred to as traditionalists. Some traditionalists consider the competition forms of today's Chinese martial arts as too commercialized and losing much of their original values.[63][64]

"Martial morality"

Traditional Chinese schools of martial arts, such as the famed Shaolin monks, often dealt with the study of martial arts not just as a means of self-defense or mental training, but as a system of ethics.[39][65] Wude (武 德) can be translated as "martial morality" and is constructed from the words wu (武), which means martial, and de (德), which means morality. Wude deals with two aspects; "Virtue of deed" and "Virtue of mind". Virtue of deed concerns social relations; morality of mind is meant to cultivate the inner harmony between the emotional mind (心; Xin) and the wisdom mind (慧; Hui). The ultimate goal is reaching "no extremity" (無 極; Wuji) – closely related to the Taoist concept of wu wei – where both wisdom and emotions are in harmony with each other.

Virtues:

| Concept | Name | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin romanization | Yale Cantonese Romanization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humility | Qian | 謙 | 谦 | qiān | hīm |

| Virtue | Cheng | 誠 | 诚 | chéng | sìhng |

| Respect | Li | 禮 | 礼 | lǐ | láih |

| Morality | Yi | 義 | 义 | yì | yih |

| Trust | Xin | 信 | xìn | seun | |

| Concept | Name | Chinese | Pinyin romanization | Yale Cantonese Romanization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Courage | Yong | 勇 | yǒng | yúhng |

| Patience | Ren | 忍 | rěn | yán |

| Endurance | Heng | 恆 | héng | hàhng |

| Perseverance | Yi | 毅 | yì | ngaih |

| Will | Zhi | 志 | zhì | ji |

Notable practitioners

Examples of well-known practitioners (武術名師) throughout history:

- Yue Fei (1103–1142 CE) was a famous Chinese general and patriot of the Song Dynasty. Styles such as Eagle Claw and Xingyiquan attribute their creation to Yue. However, there is no historical evidence to support the claim he created these styles.

- Ng Mui (late 17th century) was the legendary female founder of many Southern martial arts such as Wing Chun, and Fujian White Crane. She is often considered one of the legendary Five Elders who survived the destruction of the Shaolin Temple during the Qing Dynasty.

- Yang Luchan (1799–1872) was an important teacher of the internal martial art known as t'ai chi ch'uan in Beijing during the second half of the 19th century. Yang is known as the founder of Yang-style t'ai chi ch'uan, as well as transmitting the art to the Wu/Hao, Wu and Sun t'ai chi families.

- Ten Tigers of Canton (late 19th century) was a group of ten of the top Chinese martial arts masters in Guangdong (Canton) towards the end of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912). Wong Kei-Ying, Wong Fei Hung's father, was a member of this group.

- Wong Fei Hung (1847–1924) was considered a Chinese folk hero during the Republican period. More than one hundred Hong Kong movies were made about his life. Sammo Hung, Jackie Chan, and Jet Li have all portrayed his character in blockbuster pictures.

- Huo Yuanjia (1867–1910) was the founder of Chin Woo Athletic Association who was known for his highly publicized matches with foreigners. His biography was recently portrayed in the movie Fearless (2006).

- Ip Man (1893–1972) was a master of the Wing Chun and the first to teach this style openly. Yip Man was the teacher of Bruce Lee. Most major branches of Wing Chun taught in the West today were developed and promoted by students of Yip Man.

- Gu Ruzhang (1894–1952) was a Chinese martial artist who disseminated the Bak Siu Lum (Northern Shaolin) martial arts system across southern China in the early 20th century. Gu was known for his expertise in Iron Palm hand conditioning among other Chinese martial art training exercises.

- Bruce Lee (1940–1973) was a Chinese-American martial artist and actor who was considered an important icon in the 20th century.[66] He practiced Wing Chun and made it famous. Using Wing Chun as his base and learning from the influences of other martial arts his experience exposed him to, he later developed his own martial arts philosophy that evolved into what is now called Jeet Kune Do.

- Jackie Chan (و. 1954) is the famous Hong Kong martial artist, film actor, stuntman, action choreographer, director and producer, and a global pop culture icon, widely known for injecting physical comedy into his martial arts performances, and for performing complex stunts in many of his films.

- Jet Li (و. 1963) is the five-time sport wushu champion of China, later demonstrating his skills in cinema.

- Donnie Yen (و. 1963) is a Hong Kong actor, martial artist, film director and producer, action choreographer, and world wushu tournament medalist.

- Wu Jing (و. 1974) is a Chinese actor, director, and martial artist. He was a member of the Beijing wushu team. He started his career as action choreographer and later as an actor.

In popular culture

References to the concepts and use of Chinese martial arts can be found in popular culture. Historically, the influence of Chinese martial arts can be found in books and in the performance arts specific to Asia.[67] Recently, those influences have extended to the movies and television that targets a much wider audience. As a result, Chinese martial arts have spread beyond its ethnic roots and have a global appeal.[68][69]

Martial arts play a prominent role in the literature genre known as wuxia (武俠小說). This type of fiction is based on Chinese concepts of chivalry, a separate martial arts society (武林; Wulin) and a central theme involving martial arts.[70] Wuxia stories can be traced as far back as 2nd and 3rd century BCE, becoming popular by the Tang Dynasty and evolving into novel form by the Ming Dynasty. This genre is still extremely popular in much of Asia[71] and provides a major influence for the public perception of the martial arts.

Martial arts influences can also be found in dance, theater [72] and especially Chinese opera, of which Beijing opera is one of the best-known examples. This popular form of drama dates back to the Tang Dynasty and continues to be an example of Chinese culture. Some martial arts movements can be found in Chinese opera and some martial artists can be found as performers in Chinese operas.[73]

In modern times, Chinese martial arts have spawned the genre of cinema known as the Kung fu film. The films of Bruce Lee were instrumental in the initial burst of Chinese martial arts' popularity in the West in the 1970s.[74] Bruce Lee was the iconic international superstar that popularized Chinese martial arts in the West with his own variation of Chinese martial arts called Jeet Kune Do. It is a hybrid style of martial art that Bruce Lee practiced and mastered. Jeet Kune Do is his very own unique style of martial art that uses little to minimum movement but maximizes the effect to his opponents. The influence of Chinese martial art have been widely recognized and have a global appeal in Western cinemas starting off with Bruce Lee.

Martial artists and actors such as Jet Li and Jackie Chan have continued the appeal of movies of this genre. Jackie Chan successfully brought in a sense of humour in his fighting style in his movies. Martial arts films from China are often referred to as "kung fu movies" (功夫片), or "wire-fu" if extensive wire work is performed for special effects, and are still best known as part of the tradition of kung fu theater. (see also: wuxia, Hong Kong action cinema). The talent of these individuals have broadened Hong Kong's cinematography production and rose to popularity overseas, influencing Western cinemas.

In the west, kung fu has become a regular action staple, and makes appearances in many films that would not generally be considered "Martial Arts" films. These films include but are not limited to The Matrix franchise, Kill Bill, and The Transporter.

Martial arts themes can also be found on television networks. A U.S. network TV western series of the early 1970s called Kung Fu also served to popularize the Chinese martial arts on television. With 60 episodes over a three-year span, it was one of the first North American TV shows that tried to convey the philosophy and practice in Chinese martial arts.[75][76] The use of Chinese martial arts techniques can now be found in most TV action series, although the philosophy of Chinese martial arts is seldom portrayed in depth.

The Kung Fu Diaries: The Life and Times of a Dragon Master (1920-2001) is a work of fiction, combining aspects of biography, historical fiction, and guide to instruction purportedly from a collection of diaries or papers left by a Kung-Fu Dragon Master.[77]

Influence on hip hop

In the 1970s, Bruce Lee was beginning to gain popularity in Hollywood for his martial arts movies. The fact that he was a non-white male who portrayed self-reliance and righteous self-discipline resonated with black audiences and made him an important figure in this community.[78] Around 1973, Kung Fu movies became a hit in America across all backgrounds; however, black audiences maintained the films’ popularity well after the general public lost interest. Black youth in New York City were still going from every borough to Times Square every night to watch the latest movies.[79] Amongst these individuals were those coming from the Bronx where, during this time, hip-hop was beginning to take form. One of the pioneers responsible for the development of the foundational aspects of hip-hop was DJ Kool Herc, who began creating this new form of music by taking rhythmic breakdowns of songs and looping them. From the new music came a new form of dance known as b-boying or breakdancing, a style of street dance consisting of improvised acrobatic moves. The pioneers of this dance credit kung fu as one of its influences. Moves such as the crouching low leg sweep and “up rocking” (standing combat moves) are influenced by choreographed kung-fu fights.[80] The dancers’ ability to improvise these moves led way to battles, which were dance competitions between two dancers or crews judged on their creativity, skills, and musicality. In a documentary, Crazy Legs, a member of breakdancing group Rock Steady Crew, described the breakdancing battle being like an old kung fu movie, “where the one kung fu master says something along the lines of ‘hun your kung fu is good, but mine is better,’ then a fight erupts.” [80]

مرئيات

| لقاء نادر لبروس لي. |

| شابّان يستعرضان لكمة گوانگدونگ من فنون القتال التقليدية الصينية، مسلمو الصين. |

انظر أيضاً

- Eighteen Arms of Wushu

- Hard and soft (martial arts)

- كونگ فو (توضيح)

- List of Chinese martial arts

- Wushu (sport)

- Kwoon

- Weapons and armor in Chinese mythology

ملاحظات

المراجع

- ^ Jamieson, John; Tao, Lin; Shuhua, Zhao (2002). Kung Fu (I): An Elementary Chinese Text. The Chinese University Press. ISBN 978-962-201-867-9.

- ^ Price, Monroe (2008). Owning the Olympics: Narratives of the New China. Chinese University of Michigan Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-472-07032-9.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Fu, Zhongwen (2006) [1996]. Mastering Yang Style Taijiquan. Louis Swaine. Berkeley, California: Blue Snake Books. ISBN 1-58394-152-5.

- ^ Van de Ven, Hans J. (October 2000). Warfare in Chinese History. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 328. ISBN 90-04-11774-1.

- ^ Graff, David Andrew; Robin Higham (March 2002). A Military History of China. Westview Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0-8133-3990-1. Peers, C.J. (2006-06-27). Soldiers of the Dragon: Chinese Armies 1500 BC–1840 AD. Osprey Publishing. p. 130. ISBN 1-84603-098-6.

- ^ Green, Thomas A. (2001). Martial arts of the world: an encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 26–39. ISBN 978-1-57607-150-2.

- ^ Bonnefoy, Yves (1993-05-15). Asian Mythologies. trans. Wendy Doniger. University Of Chicago Press. p. 246. ISBN 0-226-06456-5.

- ^ Zhongyi, Tong; Cartmell, Tim (2005). The Method of Chinese Wrestling. North Atlantic Books. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-55643-609-3.

- ^ "Journal of Asian Martial Arts Volume 16". Journal of Asian Martial Arts. Via Media Pub. Co., original from Indiana University: 27. 2007. ISSN 1057-8358.

- ^ trans. and ed. Zhang Jue (1994), pp. 367–370, cited after Henning (1999) p. 321 and note 8.

- ^ Classic of Rites. Chapter 6, Yuèlìng. Line 108.

- ^ Henning, Stanley E. (Fall 1999). "Academia Encounters the Chinese Martial arts" (PDF). China Review International. 6 (2): 319–332. doi:10.1353/cri.1999.0020. ISSN 1069-5834. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-17. Retrieved 2020-07-20.

- ^ Sports & Games in Ancient China (China Spotlight Series). China Books & Periodicals Inc. December 1986. ISBN 0-8351-1534-8.

- ^ Lao, Cen (April 1997). "The Evolution of T'ai Chi Ch'uan". The International Magazine of T'ai Chi Ch'uan. Wayfarer Publications. 21 (2). ISSN 0730-1049.

- ^ Dingbo, Wu; Patrick D. Murphy (1994). Handbook of Chinese Popular Culture. Greenwood Press. p. 156. ISBN 0-313-27808-3.

- ^ Padmore, Penelope (September 2004). "Druken Fist". Black Belt Magazine. Active Interest Media: 77.

- ^ Broughton, Jeffrey L. (1999), The Bodhidharma Anthology: The Earliest Records of Zen, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21972-4. p. 8.

- ^ Canzonieri, Salvatore (February–March 1998). "History of Chinese Martial arts: Jin Dynasty to the Period of Disunity". Han Wei Wushu. 3 (9).

- ^ Christensen, Matthew B. (2016-11-15). A Geek in China: Discovering the Land of Alibaba, Bullet Trains and Dim Sum. Tuttle Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 978-1462918362.

- ^ Shahar, Meir (2000). "Epigraphy, Buddhist Historiography, and Fighting Monks: The Case of The Shaolin Monastery". Asia Major. Third Series. 13 (2): 15–36.

- ^ Shahar, Meir (December 2001). "Ming-Period Evidence of Shaolin Martial Practice". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. Harvard-Yenching Institute. 61 (2): 359–413. doi:10.2307/3558572. ISSN 0073-0548. JSTOR 3558572. S2CID 91180380.

- ^ Kansuke, Yamamoto (1994). Heiho Okugisho: The Secret of High Strategy. W.M. Hawley. ISBN 0-910704-92-9.

- ^ Kim, Sang H. (January 2001). Muyedobotongji: The Comprehensive Illustrated Manual of Martial Arts of Ancient Korea. Turtle Press. ISBN 978-1-880336-53-3.

- ^ أ ب ت Kennedy, Brian; Elizabeth Guo (2005-11-11). Chinese Martial Arts Training Manuals: A Historical Survey. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 1-55643-557-6.

- ^ Morris, Andrew (2000). "National Skills: Guoshu Martial arts and the Nanjing State, 1928–1937" in 2000 AAS Annual Meeting, March 9–12, 2000..

- ^ Brownell, Susan (1995-08-01). Training the Body for China: sports in the moral order of the people's republic. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-07646-6.

- ^ Mangan, J. A.; Fan Hong (2002-09-29). Sport in Asian Society: Past and Present. UK: Routledge. p. 244. ISBN 0-7146-5342-X.

- ^ Morris, Andrew (2004-09-13). Marrow of the Nation: A History of Sport and Physical Culture in Republican China. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24084-7.

- ^ Amos, Daniel Miles (1986) [1983]. Marginality and the Hero's Art: Martial artists in Hong Kong and Guangzhou (Canton). University of California at Los Angeles: University Microfilms International. p. 280. ASIN B00073D66A. Retrieved 2011-12-07.

- ^ Kraus, Richard Curt (2004-04-28). The Party and the Arty in China: The New Politics of Culture (State and Society in East Asia). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. p. 29. ISBN 0-7425-2720-4.

- ^ Bin, Wu; Li Xingdong; Yu Gongbao (1995-01-01). Essentials of Chinese Wushu. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 7-119-01477-3.

- ^ Riordan, Jim (1999-09-14). Sport and Physical Education in China. Spon Press (UK). ISBN 0-419-24750-5. p.15

- ^ Minutes of the 8th IWUF Congress Archived 2007-06-14 at the Wayback Machine, International Wushu Federation, December 9, 2005 (accessed 01/2007)

- ^ Zhang, Wei (1994). "Wushu".: 155–168, Greenwood Publishing Group. 9780313278082.

- ^ Yan, Xing (1995-06-01). Liu Yamin, Xing Yan (ed.). Treasure of the Chinese Nation—The Best of Chinese Wushu Shaolin Kung fu (Chinese ed.). China Books & Periodicals. ISBN 7-80024-196-3.

- ^ Tianji, Li; Du Xilian (1995-01-01). A Guide to Chinese Martial Arts. Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 7-119-01393-9.

- ^ Liang, Shou-Yu; Wen-Ching Wu (2006-04-01). Kung Fu Elements. The Way of the Dragon Publishing. ISBN 1-889659-32-0.

- ^ Schmieg, Anthony L. (December 2004). Watching Your Back: Chinese Martial Arts and Traditional Medicine. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2823-2.

- ^ أ ب Hsu, Adam (1998-04-15). The Sword Polisher's Record: The Way of Kung-Fu (1st ed.). Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3138-6.

- ^ Wong, Kiew Kit (2002-11-15). The Art of Shaolin Kung Fu: The Secrets of Kung Fu for Self-Defense, Health, and Enlightenment. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3439-3.

- ^ Kit, Wong Kiew (2002-05-01). The Complete Book of Shaolin: Comprehensive Program for Physical, Emotional, Mental and Spiritual Development. Cosmos Publishing. ISBN 983-40879-1-8.

- ^ Zhongguo da bai ke quan shu zong bian ji wei yuan hui "Zong suo yin" bian ji wei yuan hui, Zhongguo da bai ke quan shu chu ban she bian ji bu bian (1994). Zhongguo da bai ke quan shu (中国大百科全书总编辑委員会) [Baike zhishi (中国大百科, Chinese Encyclopedia)] (in الصينية). Shanghai:Xin hua shu dian jing xiao. p. 30. ISBN 7-5000-0441-9.

- ^ Mark, Bow-Sim (1981). Wushu basic training (The Chinese Wushu Research Institute book series). Chinese Wushu Research Institute. ASIN B00070I1FE.

- ^ Wu, Raymond (2007-03-20). Fundamentals of High Performance Wushu: Taolu Jumps and Spins. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-4303-1820-0.

- ^ Jwing-Ming, Yang (1998-06-25). Qigong for Health & Martial Arts, Second Edition: Exercises and Meditation (Qigong, Health and Healing) (2 ed.). YMAA Publication Center. ISBN 1-886969-57-4.

- ^ Raposa, Michael L. (November 2003). Meditation & the Martial Arts (Studies in Rel & Culture). University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-2238-0.

- ^ Ernst, Edzard; Simon Singh (2009). Trick or treatment: The undeniable facts about alternative medicine. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393337785.

- ^ Cohen, Kenneth S. (1997). The Way Of Qigong: The Art And Science Of Chinese Energy Healing. Ballantine. ISBN 0-345-42109-4.

- ^ Montaigue, Erle; Wally Simpson (March 1997). The Main Meridians (Encyclopedia Of Dim-Mak). Paladin Press. ISBN 1-58160-537-4.

- ^ Yang, Jwing-Ming (1999-06-25). Ancient Chinese Weapons, Second Edition: The Martial Arts Guide. YMAA Publication Center. ISBN 1-886969-67-1.

- ^ Wang, Ju-Rong; Wen-Ching Wu (2006-06-13). Sword Imperatives—Mastering the Kung Fu and Tai Chi Sword. The Way of the Dragon Publishing. ISBN 1-889659-25-8.

- ^ Lo, Man Kam (2001-11-01). Police Kung Fu: The Personal Combat Handbook of the Taiwan National Police. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3271-4.

- ^ Shengli, Lu (2006-02-09). Combat Techniques of Taiji, Xingyi, and Bagua: Principles and Practices of Internal Martial Arts. trans. Zhang Yun. Blue Snake Books. ISBN 1-58394-145-2.

- ^ Hui, Mizhou (July 1996). San Shou Kung Fu Of The Chinese Red Army: Practical Skills And Theory Of Unarmed Combat. Paladin Press. ISBN 0-87364-884-6.

- ^ Liang, Shou-Yu; Tai D. Ngo (1997-04-25). Chinese Fast Wrestling for Fighting: The Art of San Shou Kuai Jiao Throws, Takedowns, & Ground-Fighting. YMAA Publication Center. ISBN 1-886969-49-3.

- ^ أ ب Bolelli, Daniele (2003-02-20). On the Warrior's Path: Philosophy, Fighting, and Martial Arts Mythology. Frog Books. ISBN 1-58394-066-9.

- ^ Kane, Lawrence A. (2005). The Way of Kata. YMAA Publication Center. p. 56. ISBN 1-59439-058-4.

- ^ Johnson, Ian; Sue Feng (August 20, 2008). "Inner Peace? Olympic Sport? A Fight Brews". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ Fowler, Geoffrey; Juliet Ye (December 14, 2007). "Kung Fu Monks Don't Get a Kick Out of Fighting". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ Seabrook, Jamie A. (2003). Martial Arts Revealed. iUniverse. p. 20. ISBN 0-595-28247-4.

- ^ Verstappe, Stefan (2014-09-04). "Three hidden meanings of Chinese forms". Archived from the original on 2014-09-04. Retrieved 2019-04-12.

- ^ Shoude, Xie (1999). International Wushu Competition Routines. Hai Feng Publishing Co., Ltd. ISBN 962-238-153-7.

- ^ Parry, Richard Lloyd (August 16, 2008). "Kung fu warriors fight for martial art's future". London: Times Online. Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ^ Polly, Matthew (2007). American Shaolin: Flying Kicks, Buddhist Monks, and the Legend of Iron Crotch : an Odyssey in the New China. Gotham. ISBN 978-1-59240-262-5.

- ^ Deng, Ming-dao (1990-12-19). Scholar Warrior: An Introduction to the Tao in Everyday Life (1st ed.). HarperOne. ISBN 0-06-250232-8.

- ^ Joel Stein (1999-06-14). "ТІМЕ 100: Bruce Lee". Time. Archived from the original on January 14, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ Mroz, Daniel (2012). The Dancing Word: An Embodied Approach to the Preparation of Performers and the Composition of Performances. Rodopi. ISBN 978-9401200264.

- ^ Prashad, Vijay (2002-11-18). Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting: Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity. Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-5011-3.

- ^ Kato, M. T. (2007-02-08). From Kung Fu to Hip Hop: Globalization, Revolution, and Popular Culture (Suny Series, Explorations in Postcolonial Studies). State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6992-7.

- ^ Denton, Kirk A.; Bruce Fulton; Sharalyn Orbaugh (2003-08-15). "Chapter 87. Martial-Arts Fiction and Jin Yong". In Joshua S. Mostow (ed.). The Columbia Companion to Modern East Asian Literature. Columbia University Press. pp. 509. ISBN 0-231-11314-5.

- ^ Cao, Zhenwen (1994). "Chapter 13. Chinese Gallant Fiction". In Dingbo Wu, Patrick D. Murphy (ed.). Handbook of Chinese Popular Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 237. ISBN 0313278083.

- ^ Mroz, Daniel (July 2009). "From Movement to Action: Martial Arts in the Practice of Devised Physical Theatre". Practice of Devised Physical Theatre, Studies in Theatre and Performance. 29 (2).

- ^ Mroz, Daniel (2011-04-29). The Dancing Word: An Embodied Approach to the Preparation of Performers and the Composition of Performances. (Consciousness, Literature & the Arts). Rodopi. ISBN 978-9042033306.

- ^ Schneiderman, R. M. (2009-05-23). "Contender Shores Up Karate's Reputation Among U.F.C. Fans". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

- ^ Pilato, Herbie J. (1993-05-15). Kung Fu Book of Caine (1st ed.). Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-1826-6.

- ^ Carradine, David (1993-01-15). Spirit of Shaolin. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-1828-2.

- ^ Patrick Grant, "Foreword" to The Kung Fu Diaries: The Life and Times of a Dragon Master (1920-2001). Leicestershire UK: The Book Guild Ltd 2018, ix ISBN 9781912362370

- ^ Phil Hoad, "Why Bruce Lee and kung fu films hit home with black audiences", The Guardian

- ^ Wisdom B, "Know Your Hip-Hop History: The B-Boy", Throwback Magazine

- ^ أ ب Chris Friedman, "Kung Fu Influences Aspects of Hip Hop Culture Like Break Dancing"

- CS1 الصينية-language sources (zh)

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing traditional Chinese-language text

- Articles containing Pinyin-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2018

- All articles with self-published sources

- Articles with self-published sources from February 2020

- المقالات needing additional references from March 2017

- كل المقالات needing additional references

- مقالات ذات عبارات محل شك

- رياضات قتالية

- فنون قتالية

- فنون قتالية صينية