تعاليم شوروباك

تعاليم شوروپاك (أو تعاليم شوروپاك[1] ابن أوبارا-توتو) هي مثال بارز من أدب الحكمة السومري.[2] كان أدب الحكمة، الذي يهدف إلى تعليم التقوى الصحيحة، وغرس الفضيلة، والحفاظ على معايير المجتمع ، شائعاً في أرجاء الشرق الأدنى القديم.[3] افتتاحية التعاليم تضع النص في القِدم السحيق بالقول: "في تلك الأيام، في تلك الأزمنة البعيدة، في تلك الليالي، في تلك الليالي البعيدة، في تلك السنوات، في تلك السنوات البعيدة." الوصايا أتت على لسان الملك شوروپـّاك (سو.كور.روكي)، ابن أوبارا-توتو. أوبارا-توتو مسجل في معظم النسخ المتواجدة لقائمة الملوك السومريين كآخر ملك على سومر قبل الطوفان. أوبارا-توتو مذكور بشكل عابر في اللوح الحادي عشر من ملحمة جلجامش، حيث يـُعرَّف بأنه والد أوتناپشتم، الشخص الذي أمره الإله إيا أن يصنع سفينة لكي ينجو من الطوفان القادم.[4] ولكونها كانت مجموعة مع ألواح مسمارية أخرى من أبو الصلابيخ، فإن التعاليم أُرِّخت بأنها تعود إلى مطلع الألفية الثالثة ق.م.، لتصبح بين أقدم الأعمال الأدبية المعروفة.

النص هو عبارة عن تحذيرات من شروباك يوجهها لابنه الذي سيصبح لاحقاً بطل الطوفان زيوسودرا (بالأكدية: أوتناپشتن). عدا ذلك فإسم شوروباك تحمله واحدة من خمس مدن من قبل الطوفان في التقليد السومري،[5] الاسم "شوروپاك" يظهر في مخطوطة لـ قائمة الملوك السومرية (WB-62، مكتوبة سو.كور.لام) حيث فـُهِمت بأنها جيل إضافي بين أوبارا-توتو و زيوسودرا، المذكورين في كل النسخ الأخرى كأب وابن. ويفيد لامبرت أن ثمة اقتراح أن الجيل الإضافي لعله نشأ من كنية الأب ("رجل شوروپاك") التي فـُهِمت بشكل خاطئ كإسم شخص إضافي.[6]إلا أن هذه الكنية الموجودة في اللوح 11 من ملحمة جلجامش هي توصيف لأوتنابشتم، وليس لأبيه.

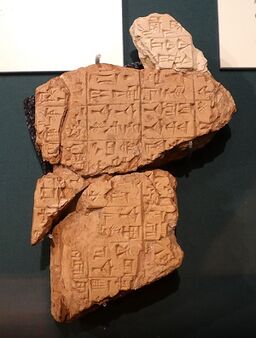

لوح أبو الصلابيخ، الذي يعود إلى منتصف الألفية الثالثة ق.م.،[7] هو أقدم نسخة موجودة، والنسخ الباقية العديدة تشهد على الشعبية المتواصلة لذلك الأدب في المحفوظات الأدبية السومرية/الأكدية.[8]

النصائح في القوائم الثلاث المترابطة بليغة، وتحتل سطراً إلى ثلاثة أسطر من الكتابة المسمارية. بعض النصائح هي عملية بحتة: لا تضع حقلاً على طريق؛ .... لا تحفر بئراً في حقلك لأن الناس سوف يلحقون بك الضرر. (السطور 15–18). النصائح الأخلاقية تليها النتائج العملية السلبية لهذا التعدي: لا تتلاعب بشابة متزوجة: القذف قد يكون وخيماً. (السطور 32–34). رأي المجتمع وإمكانية القذف (السطر 35) ترفـّع عن الصغائر بغض النظر عن رأي رفاق البلاط (السطر 62) أو رفاق السوق ، حيث الإهانات والكلام الأحمق يسترعي انتباه الأرض. (السطر 142).

تضم التعاليم مبادئ تم تضمينها لاحقاً في الوصايا العشر،[9]: السطر 50: لا تشتط في اللعن (الوصية الثالثة)؛ السطر 28: لا تقتل (الوصية السادسة)؛ السطور 33–34: لا تمزح مع، أو تجالس وحيداً إمرأة متزوجة (الوصية السابعة)؛ السطور 28–31: لا تسرق ولا تأخذ ما ليس لك (الوصية الثامنة)؛ والسطر 36: لا تنطق بأكاذيب (الوصية التاسعة). وأقوال أخرى منعكسة في سفر الأمثال التوراتي.

مقتطفات

في تلك الأيام، long ago, in those nights, in those distant nights, in those years, in those long-gone years, in those days, lived the sage in the land who knew how to speak in elaborate language; Šuruppak, the son of Ubara-Tutu, gave admonitions to his son Zi-ud-sura: My son, let me give you admonitions: you should pay close attention! Zi-ud-sura, let me have a word with you: you must pay close attention! Do not neglect my admonitions! Do not transgress the words I speak! The admonitions of an old man are precious, you should obey them!

Don't buy an ass that brays; he will split(?) your diaphragm(?)

You don't have to stand surety for someone else; that man then has a grip on you. You shouldn't let another stand surety for you either (that man will despise you)

You must not steal anything; you must not yourself ...(?). You shouldn't break into a house, you shouldn't covet the cash box(?). A thief is a lion, but as soon as he is caught he becomes a slave. My son, you must not commit robbery, you must not cut yourself with an axe.

You must not speak indecently; later that becomes a trap for you

You should not travel at night: she can hide both good and evil .

You must not have sex with your slave girl: she will devour you.

The eye of the slanderer always moves about like a spindle. You should never stay in his company; his intentions(?) must have no effect(?) on you

You mustn't brag in the beer halls like a man of deceit, then your word will be trusted

The palace is like a mighty stream; the middle of it is like spearing bulls; what flows into it is never enough and what flows out can never be stopped

You can't pass judgment when you drink beer.

Heaven is far, earth most precious, but it is with heaven that you increase your goods and all foreign lands breathe beneath it.

Fate is a wet bank; you can slip on it .

A woman with her own property ruins the house.

الدين

The later, more extensive versions of the play from the Old Babylonian period are divided into three chapters, each with a short introduction and conclusion. In the conclusion of parts one and two, religion comes into play, particularly through references to Utu , the god of justice. The conclusion of part one reads:

- The hero is unique, he alone is the equal of many

- Utu is unique, he alone is the equal of many

- Standing with the hero will prolong your life!

- Standing with Utu extends your life!

- Šuruppak gave these admonitions to his son

- Šuruppak, the son of Ubara-Tutu

- gave these admonitions to his son Ziusudra.

However, no references to the gods can be found in the admonitions themselves, and in the oldest versions of تل أبو الصلابيخ the introductions and closures are missing. It is therefore quite possible that the piece was originally secular in nature and was collected over a long period of time, but that it was later placed in a religious framework by the priests.

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ Hesiod (2006). Most, Glenn W. (ed.). Theogony, Works and Days, Testimonia. Loeb Classical Library. Harvard University Press. p. xlvi.

- ^ "أهم عمل في أدب الحكمة بالسومرية"، كما يؤكد پول-ألان بوليو، في Richard J. Clifford, ed., Wisdom Literature in Mesopotamia and Israel 2007:4.

- ^ Instructions of Shuruppak: from W. G. Lambert (1996) Babylonian Wisdom Literature. (Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake, Indiana) Includes on-line English translation of the text.

- ^ George, Andrew R. (2003). The Epic of Gilgamesh: The Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian. Penguin Classics. ISBN 9780241289907.

- ^ حسب نشأة إريدو، الحق الملكي نزل من السماء، وتأسست أول المدن: إريدو و باد-تيبيرا و لارسا و سيپار و شوروپاك.

- ^ Lambert, W.G. (1996). Babylonian Wisdom Literature. Eisenbrauns. p. 92. ISBN 9780931464942. Retrieved 2015-06-03.

- ^ Biggs, Robert D. (1974). Inscriptions from Tell Abū Ṣalābīkh (PDF). Oriental Institute Publications. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-62202-9.

- ^ وتوجد نسختان متشظيتان بالأكدية، من القرن 15 ق.م. ومن نهاية الألفية الثانية ق.م.: "يتضح أثرها الكبير وشعبيتها من خلال العدد الكبير من مخطوطاتها التي بقيت" (Beaulieu in Clifford 2007:4).

- ^ ملاحظات موقع مجموعة سخوين ، من لوح سومري حديث من حوالي 1900–1700 ق.م.

للاستزادة

- Bendt Alster The Instructions of Shuruppak. A Sumerian Proverb Collection, (Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag) 1974.