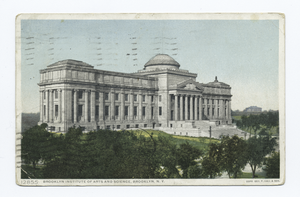

متحف بروكلن

Brooklyn Museum | |

Main entrance of the museum at night, 2015 | |

| الموقع | 200 Eastern Parkway Brooklyn, NY 11238 |

|---|---|

| الإحداثيات | 40°40′16.7″N 73°57′49.5″W / 40.671306°N 73.963750°W |

| بُنيَ | 1895 |

| المعماري | McKim, Mead & White; French, Daniel Chester |

| الطراز المعماري | Beaux-Arts |

| NRHP reference No. | خطأ لوا: invalid capture index %2 in replacement string. |

| أضيف إلى NRHP | August 22, 1977 |

The Brooklyn Museum is an art museum located in the New York City borough of Brooklyn. At 560,000 square feet (52,000 m2), the museum is New York City's third largest in physical size and holds an art collection with roughly 500,000 objects. [2]

Located near the Prospect Heights, Crown Heights, Flatbush, and Park Slope neighborhoods of Brooklyn and founded in 1895, the Beaux-Arts building, designed by McKim, Mead and White, was planned to be the largest art museum in the world. The museum initially struggled to maintain its building and collection, only to be revitalized in the late 20th century, thanks to major renovations. Significant areas of the collection include antiquities, specifically their collection of Egyptian antiquities spanning over 3,000 years. European, African, Oceanic, and Japanese art make for notable antiquities collections as well. American art is heavily represented, starting at the Colonial period. Artists represented in the collection include Mark Rothko, Edward Hopper, Norman Rockwell, Winslow Homer, Edgar Degas, Georgia O'Keeffe, and Max Weber. The museum features the Steinberg Family Sculpture Garden, which features salvaged architectural elements from throughout New York City.[3]

History

The roots of the Brooklyn Museum extend back to the 1823 founding by Augustus Graham of the Brooklyn Apprentices' Library in Brooklyn Heights. The Library moved into the Brooklyn Lyceum building on Washington Street in 1841. Two years later the institutions merged to form the Brooklyn Institute, which offered exhibitions of painting and sculpture and lectures on diverse subjects. In 1890, under its director Franklin Hooper, Institute leaders reorganized as the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences and began planning the Brooklyn Museum. The museum remained a subdivision of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, along with the Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, and the Brooklyn Children's Museum until the 1970s when all became independent.[4]

Opened in 1897, the Brooklyn Museum building is a steel frame structure clad in masonry, designed in the neoclassical style by the architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White and built by the Carlin Construction Company. The original design for the Brooklyn Museum proposed a structure four times as large as what was built from 1893 through 1927, when construction ended. After Brooklyn became part of greater New York City in 1898, support for the project diminished.[5] Daniel Chester French, the sculptor of the statue of Abraham Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial, was the principal designer of the pediment sculptures and the monolithic 12.5-foot (3.8 m) figures along the cornice. The figures were created by 11 sculptors and carved by the Piccirilli Brothers. French also designed the two allegorical figures Brooklyn and Manhattan currently flanking the museum's entrance, created in 1916 for the Brooklyn approach to the Manhattan Bridge and relocated to the museum in 1963.

By 1920, the New York City Subway reached the museum with a subway station; this greatly improved access to the once-isolated museum from Manhattan and other outer boroughs.

The Brooklyn Institute's director Franklin Hooper was the museum's first director, succeeded by William Henry Fox who served from 1914 to 1934. He was followed by Philip Newell Youtz (1934–1938), Laurance Page Roberts (1939–1946), Isabel Spaulding Roberts (1943–1946), Charles Nagel, Jr. (1946–1955), and Edgar Craig Schenck (1955–1959).

Thomas S. Buechner became the museum's director in 1960, making him one of the youngest directors in the country. Buechner oversaw a major transformation in the way the museum displayed art and brought some one thousand works that had languished in the museum's store rooms and put them on display. Buechner played a pivotal role in rescuing the Daniel Chester French sculptures from destruction due to an expansion project at the Manhattan Bridge in the 1960s.[6]

Duncan F. Cameron held the post from 1971 to 1973, with Michael Botwinick succeeding him (1974–1982) and Linda S. Ferber acting director for part of 1983 until Robert T. Buck became director in 1983 and served until 1996.

The Brooklyn Museum changed its name to Brooklyn Museum of Art in 1997, shortly before the start of Arnold L. Lehman's term as director. On March 12, 2004, the museum announced that it would revert to its previous name. In April 2004, the museum opened the James Polshek-designed entrance pavilion on the Eastern Parkway facade.[7] In September 2014, Lehman announced that he was planning to retire around June 2015.[8] In May 2015, Creative Time president and artistic director Anne Pasternak was named the museum's next director; she assumed the position on September 1, 2015.[9]

Funding

The Brooklyn Museum, along with numerous other New York institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, is part of the Cultural Institutions Group (CIG). Member institutions occupy land or buildings owned by the City of New York and derive part of their yearly funding from the city. The Brooklyn Museum also supplements its earned income with funding from Federal and State governments, as well as with donations by individuals and organizations.

In 1999, the museum hosted the Charles Saatchi exhibition Sensation, resulting in a court battle[10] over New York City's municipal funding of institutions exhibiting controversial art, eventually decided in favor of the museum on First Amendment grounds.[11][12][13]

In 2005, the museum was among 406 New York City arts and social service institutions to receive part of a $20 million grant from the Carnegie Corporation, in turn funded by New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg.[14][15]

Major benefactors include Frank Lusk Babbott. The museum is the site of the annual Brooklyn Artists Ball which has included celebrity hosts such as Sarah Jessica Parker and Liv Tyler.[16]

Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic and its negative impact on museum revenue, the museum raised funds for an endowment to pay for collections care by selling or deaccessioning works of art. The endowment will allow the museum to direct annual fundraising revenues dedicated to conservation and collection care to other purposes. The October 2020 sale consisted of 12 works by artists including Lucas Cranach the Elder, Gustave Courbet, and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot.[17] Other sales throughout October 2020 included Modernist artists.[18] Though usually prohibited by the Association of Art Museum Directors, the association allowed such sales to proceed for a two-year window through 2022 in response to the effects of the pandemic.[19]

Art and exhibitions

The Brooklyn Museum exhibits collections that seek to embody the artistic heritage of world cultures. The museum is well known for its expansive collections of Egyptian and African art, in addition to 17th-, 18th-, 19th-, and 20th-century paintings, sculpture, and decorative arts throughout a wide range of schools.

In 2002, the museum received the work The Dinner Party, by feminist artist Judy Chicago, as a gift from The Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation. Its permanent exhibition began in 2007, as a centerpiece for the museum's Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. In 2004, the Brooklyn Museum featured Manifest Destiny, an 8-by-24-foot (2.4 m × 7.3 m) oil-on-wood mural by Alexis Rockman that was commissioned by the museum as a centerpiece for the second-floor Mezzanine Gallery and marked the opening of the museum's renovated Grand Lobby and plaza.[20][21] Other exhibitions have showcased the works of various contemporary artists including Patrick Kelly, Chuck Close, Denis Peterson, Ron Mueck, Takashi Murakami, Mat Benote,[22] Kiki Smith, Jim Dine, Robert Rauschenberg, Ching Ho Cheng, Sylvia Sleigh and William Wegman, and a 2004 survey show of work by Brooklyn artists, Open House: Working in Brooklyn.[23]

In 2008, curator Edna Russman announced that she believes 10 out of 30 works of Coptic art held in the museum's collection—second-largest in North America are fake. The artworks were exhibited starting in 2009.[24]

Costumes from The Crown and The Queen's Gambit television series were put on display as part of its virtual exhibition "The Queen and the Crown" in November 2020.[25][26]

Collections

Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Near Eastern Art

The Brooklyn Museum has been building a collection of Egyptian artifacts since the beginning of the twentieth century, incorporating both collections purchased from others, such as that of American Egyptologist Charles Edwin Wilbour, whose heirs also donated his library to become the museum's Wilbour Library of Egyptology, and objects obtained during museum-sponsored archeological excavations. The Egyptian collection includes objects ranging from statuary, such as the well-known "Bird Lady" terra cotta figure, to papyrus documents (among others the Brooklyn Papyrus).[27]

The Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Near Eastern collections are housed in a series of galleries in the museum. Egyptian artifacts can be found in the long-term exhibit, Egypt Reborn: Art for Eternity, as well as in the Martha A. and Robert S. Rubin Galleries. Near Eastern artifacts are located in the Hagop Kevorkian Gallery.[27]

Selections from the Egyptian collection

American art

The museum's collection of American art dates its first bequest of Francis Guy's Winter Scene in Brooklyn in 1846. In 1855, the museum officially designated a collection of American Art, with the first work commissioned for the collection being a landscape painting by Asher B. Durand. Items in the American Art collection include portraits, pastels, sculptures, and prints; all items in the collection date to between c. 1720 and c. 1945.

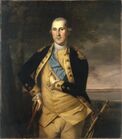

Represented in the American art collection are works by artists such as William Edmondson (Angel, date unknown), John Singer Sargent's Paul César Helleu sketching his wife Alice Guérin (ca. 1889); Georgia O'Keeffe's Dark Tree Trunks (ca. 1946), and Winslow Homer's Eight Bells (ca. 1887). Among the most famous works in the collection are Gilbert Stuart's portrait of George Washington and Edward Hicks's The Peaceable Kingdom. The museum also holds a collection by Emil Fuchs.[28]

Works from the American art collection can be found in various areas of the museum, including in the Steinberg Family Sculpture Garden and in the exhibit, American Identities: A New Look, which is contained within the museum's Visible Storage ▪ Study Center.[29] In total, there are approximately 2,000 American Art objects held in storage.[30]

Selections from the American collection

Charles Willson Peale, George Washington, c. 1776

Samuel Morse, Portrait of John Adams, 1816

Edward Hicks, The Peaceable Kingdom, c. 1830-1840

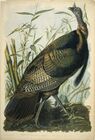

John J. Audubon, Wild Turkey, lithograph, c. 1861

Eastman Johnson, A Ride for Liberty – The Fugitive Slaves, c. 1862

Albert Pinkham Ryder, Evening Glow The Old Red Cow, 1870-1875

Albert Pinkham Ryder, The Waste of Waters is Their Field, 1880.

Winslow Homer, The Northeaster, c. 1883

Ralph Albert Blakelock, Moonlight, 1885.

George Inness, Sunrise, 1887

Thomas Eakins, Letitia Wilson Jordan, 1888

John Singer Sargent, Paul César Helleu Sketching with His Wife, 1889

Mary Cassatt, La Toilette, c. 1889–1894.

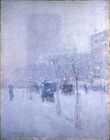

Childe Hassam, Late Afternoon, New York, Winter, c. 1900

Thomas Eakins, William Rush Carving his Allegorical Figure of the Schuylkill River, 1908

William Glackens, Nude with Apple, 1909-1910

George Bellows, A Morning Snow--Hudson River, 1910

Adolph Weinman, Night, c. 1910

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Arch, c. 1914

Georgia O'Keeffe, Blue 1, 1916

Marsden Hartley, Landscape, New Mexico, 1916-1920

Asian art

In 2019, the museum reopened its Japanese and Chinese exhibits, after reinstalling its Korean section in 2017.[31] The Chinese section offers pieces from more than 5,000 years of Chinese art and will show contemporary pieces on a regular schedule.[31] The Japanese gallery, with its 7,000 pieces, is the largest of the museum's Asian collection and is known for its works from the Ainu people.[32] The museum is also home to works from Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan and southeast Asia.[33]

Arts of Africa

The oldest acquisitions in the African art collection were collected by the museum in 1900, shortly after the museum's founding. The collection was expanded in 1922 with items originating largely in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In 1923 the museum hosted one of the first exhibitions of African art in the United States.

With more than 5,000 items in its collection, the Brooklyn Museum boasts one of the largest collections of African art in any American art museum. Although the title of the collection suggests that it includes art from all of the African continent, works from Africa are sub-categorized among a number of collections. Sub-Saharan art from West and Central Africa are collected under the banner of African Art, while North African and Egyptian art works are grouped with the Islamic and Egyptian art collections, respectively.

The African art collection covers 2,500 years of human history and includes sculpture, jewellery, masks, and religious artifacts from more than 100 African cultures. Noteworthy items in this collection include a carved ndop figure of a Kuba king, believed to be among the oldest extant ndop carvings, and a Lulua mother-and-child figure.[34]

In 2018, the museum drew criticism from groups including Decolonize This Place for its hiring of a white woman as Consulting Curator of African Arts.[35][36]

Selections from the African collection

Kuba Ndop Portrait.

Arts of the Pacific Islands

The museum's collection of Pacific Islands art began in 1900 with the acquisition of 100 wooden figures and shadow puppets from New Guinea and the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia); since that base, the collection has grown to encompass close to 5,000 works. Art in this collection is sourced to numerous Pacific and Indian Ocean islands including Hawaii and New Zealand, as well as less-populous islands such as Rapa Nui and Vanuatu. Many of the Marquesan items in the collection were acquired by the museum from famed Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl.[37]

Art objects in this collection are crafted from a wide variety of materials. The museum lists "coconut fiber, feathers, shells, clay, bone, human hair, wood, moss, and spider webs"[37] as among the materials used to make artworks that include masks, tapa cloths, sculpture, and jewellery.

Arts of the Islamic world

The museum also has art objects and historical texts produced by Muslim artists or about Muslim figures and cultures.[38]

Selections from the Islamic world collection

Bahram Gur and Courtiers Entertained by Barbad the Musician, Page from Shahnama of Ferdowsi.

Mihr 'Ali (Iranian, active ca. 1800–1830). Portrait of Fath-Ali Shah Qajar, 1815.

Muhammad Hasan (Persian, active 1808–1840). Prince Yahya, ca. 1830s.

Bowl with Kufic Inscription, 10th century.

The Jarvis Collection of Native American Plains Art

The Museum has a collection of Native America Artifacts acquired by Dr. Nathan Sturges Jarvis (surgeon) who was stationed at Fort Snelling, Minnesota 1833–36.[39]

The Museum has a collection of Native America Artifacts acquired by Dr. Nathan Sturges Jarvis (surgeon) who was stationed at Fort Snelling, Minnesota 1833–36.[39]

Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art

The museum's center for feminist art opened in 2007; it is dedicated to preserving the history of the movement since the late 20th century, as well as raising awareness of feminist contributions to art, and informing the future of this area of artistic dialogue. Along with an exhibition space and library, the center features a gallery housing a masterwork by Judy Chicago, a large installation called The Dinner Party (1974-1979).[40]

European art

The Brooklyn Museum has among others late Gothic and Early Italian Renaissance paintings by Lorenzo di Niccolo ("Scenes from the life of Saint Lawrence"), Sano di Pietro, Nardo di Cione, Lorenzo Monaco, Donato de' Bardi ("Saint Jerome"), Giovanni Bellini. It has Dutch paintings by Frans Hals, Gerard Dou, and Thomas de Keyser as well as others. It has 19th-century French paintings by Charles Daubigny, Narcisse Virgilio Díaz, Eugène Boudin ("Port, Le Havre"), Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas, Gustave Caillebotte ("Railway Bridge at Argenteuil"), Claude Monet ("Doges Palace, Venice"), the French sculptor Alfred Barye, Camille Pissarro, and Paul Cézanne as well as many others.

Selections from the European collection

Lorenzo di Niccolò, Saint Lawrence Buried in Saint Stephen's Tomb, 1410–1414, tempera and tooled gold on poplar, 33 × 36 cm

Sano di Pietro, Triptych of Madonna with Child, St. James and St. John the Evangelist, ca. 1460 and 1462

Eugène Delacroix, Desdemona Cursed by her Father (Desdemona maudite par son père), c. 1850-1854

Honoré Daumier, The Two Colleagues (Lawyers) (Les deux confrères Avocats), between 1865 and 1870

Gustave Courbet, The Edge of the Pool, 1867

Edgar Degas, Portrait de Mlle Eugénie Fiocre, 1867-1868

Alfred Sisley, Flood at Moret (Inondation à Moret), 1879

Gustave Caillebotte, Apple Tree in Bloom (Pommier en fleurs), c. 1885

Jules Breton, Fin du travail (The End of the Working Day), c.1886-1887

Vincent van Gogh, Cypresses (Les Cyprès), 1889, Reed pen, graphite, quill, brown ink and black ink on white wove latune et cie balcons paper,

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge (Au Moulin Rouge), c. 1892.

Claude Monet, The Church at Vernon, 1894

Claude Monet, Houses of Parliament Sunlight Effect (Le Parlement effet de soleil), 1903

Claude Monet, The Doge's Palace (Le Palais ducal), 1908

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Les Vignes à Cagnes, 1908.

André Derain, Landscape in Provence (Paysage de Provence)" (c. 1908)

Libraries and archives

The Brooklyn Museum Libraries and Archives hold approximately 300,000 volumes and over 3,200-foot (980 m) of archives. The collection began in 1823 and is housed in facilities that underwent renovations in 1965, 1984 and 2014.[41][42][43]

Programs

In 2000, the Brooklyn Museum started the Museum Apprentice Program in which the museum hires teenage high schoolers to give tours in the museum's galleries during the summer, assist with the museum's weekend family programs throughout the year, participate in talks with museum curators, serve as a teen advisory board to the museum, and help plan teen events.

The first Saturday of each month, the Brooklyn Museum stays open until 11 pm. General admission is waived from 5 to 11 pm, although some ticketed exhibitions may require an entrance fee. Regular first Saturday activities include educational family-oriented activities such as collection-based art workshops, gallery tours, lectures, live performances dance parties.[44]

The museum has posted many pieces to a digital collection online which features a user-based tagging system that allows the public to tag and curate sets of objects online, as well as solicit additional scholarship contributions.[45]

The Museum Education Fellowship Program is a ten-month position in which Fellows acquire theoretical and practical skills to lead K-12 school group visits with a focus on various topics from the collection.

School Youth and Family Fellows teach Gallery Studio Programs and School Partnerships while Adult and Public Programs Fellows curate and organize Thursday night as well as First Saturday Programming.

The museum has also received attention for its recent ASK App in which visitors can interface with staff and educators regarding works in the collection through a mobile application downloadable through the Apple and Google application stores.[46]

"Populism"

Attendance at the Brooklyn Museum has been in decline in recent years, from a high "decades ago" of nearly one million visitors per year to more recent figures of 585,000 (1998) and 326,000 (2009).[47]

The New York Times attributed this drop partially to the policies instituted by then-current director Arnold Lehman, who has chosen to focus the museum's energy on "populism", with exhibits on topics such as "Star Wars movies and hip-hop music"[47] rather than on more classical art topics. Lehman had also brought more controversial exhibits, such as a 1999 show that included Chris Ofili's infamous dung-decorated The Holy Virgin Mary, to the museum.[48] According to the Times:

The quality of their exhibitions has lessened", said Robert Storr, the dean of the Yale University School of Art and a Brooklynite. "'Star Wars' shows the worst kind of populism. I don't think they really understand where they are. The middle of the art world is now in Brooklyn; it's an increasingly sophisticated audience and always was one.[47]

On the other hand, Lehman points out that the demographics of museum attendees are showing a new level of diversity. According to The New York Times, "the average age [of museum attendees in a 2008 survey] was 35, a large portion of the visitors (40 percent) came from Brooklyn, and more than 40 percent identified themselves as people of color." Lehman asserts that the museum's interest is in being welcoming and attractive to all potential museum attendees, rather than simply amassing large numbers of them.[49]

Works and publications

- We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-1985

- Choi, Connie H.; Hermo, Carmen; Hockley, Rujeko; Morris, Catherine; Weissberg, Stephanie (2017). Morris, Catherine; Hockley, Rujeko (eds.). We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85 / A Sourcebook (Exhibition catalog). Brooklyn, New York: Brooklyn Museum. ISBN 978-0-872-73183-7. OCLC 964698467. – Published on the occasion of an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, April 21-September 17, 2017

See also

- Brooklyn Visual Heritage

- Education in New York City

- List of cases argued by Floyd Abrams

- List of museums and cultural institutions in New York City

References

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. يناير 23, 2007.

- ^ Bahr, Sarah (June 17, 2010). "Brooklyn Museum to Receive $50 Million Gift From City of New York". The New York Times. Retrieved 2022-01-28.

- ^ Spelling, Simon. "Entertainment: Brooklyn Museum". New York. Archived from the original on 2012-05-08. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ {cite web |url=http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/about/building.php |title=About: The Museum's Building |publisher=Brooklyn Museum| access-date=2014-08-01}}

- ^ White, Norval; Wilensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (June 9, 2010). AIA Guide to New York City. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 605–606. ISBN 978-0195383867. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ Grimes, William (June 17, 2010). "Thomas S. Buechner, Former Director of Brooklyn Museum, Dies at 83". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ^ Muschamp, Herbert (July 16, 2004). "Brooklyn's Radiant New Art Palace". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-10-27.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (September 9, 2014). "Brooklyn Museum's Longtime Director Plans to Retire". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-09-16.

- ^ Lescaze, Zoë (19 May 2015). "Anne Pasternak Named Director of the Brooklyn Museum". ArtNews. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ^ Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences v. City of New York, 64 F.Supp.2d 184 (E.D.N.Y. Nov 01, 1999)

- ^ "BROOKLYN INSTITUTE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES v. CITY OF NEW YORK". ncac.org. Archived from the original on 2015-03-13. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ "Lessons from the Brooklyn Museum Controversy" (PDF). Hettingern.people.cofc.edu. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Roberts, Sam (July 6, 2005). "City Groups Get Bloomberg Gift of $20 Million". The New York Times.

- ^ "Carnegie Corporation of New York announces twenty million dollars in New York City grants" (Press release). Carnegie Corporation. July 5, 2005. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ "Brooklyn Museum's Artists Ball: Sarah Jessica Parker & Liv Tyler Broadcast Their Art Credit". Huffington Post. May 5, 2011. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (16 September 2020). "Brooklyn Museum to Sell 12 Works as Pandemic Changes the Rules". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Kenney, Nancy (16 October 2020). "Brooklyn Museum steams ahead on deaccessioning". www.theartnewspaper.com. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "Association Of Art Museum Directors' Board Of Trustees Approves Resolution to Provide Additional Financial Flexibility to Art Museums During Pandemic Crisis" (PDF). Association of Art Museum Directors. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Yablonsky, Linda (November 4, 2004). "New York's Watery New Grave". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ^ "Alexis Rockman Mural of Future Brooklyn Celebrates Opening of the Brooklyn Museum New Front Entrance and Plaza" (PDF) (Press release). Brooklyn Museum. March 2004. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ^ Mclaughlin, Mike (September 28, 2009). "Hangin' with big boys: Artist slips in stealth exhibit at Brooklyn Museum". Daily News. New York. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ "Open House: Working in Brooklyn" (Press release). Brooklyn Museum. April 17, 2004. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ Usborne, David (July 2, 2008). "New York museum admits third of its Coptic art is fake". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ^ Soriano, Jianne (November 4, 2020). "Costumes From Netflix's "The Queen's Gambit" And "The Crown" Featured At The Brooklyn Museum". Tatler Asia. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "The Queen and The Crown: A Virtual Exhibition of Costumes from "The Queen's Gambit" and "The Crown"". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ أ ب "Collections: Egyptian, Classical, Ancient Near Eastern Art: History". The Brooklyn Museum. Archived from the original on 2014-06-24. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ "Collections: Emil Fuchs". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ "Collections: History". The Brooklyn Museum. Archived from the original on 2014-06-24. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ "Confounding Expectations with Brooklyn Museum's Laval Bryant". Virgin Holidays. Retrieved 2018-11-08.

- ^ أ ب Heinrich, Will (26 December 2019). "5,000 Years of Asian Art in 1 Single, Thrilling Conversation". The New York Times.

- ^ Williamson, Alex (19 August 2019). "Revamped Asian galleries at Brooklyn Museum set to reopen after 6 years". Brooklyn Eagle.

- ^ "Brooklyn Museum". www.brooklynmuseum.org.

- ^ "Collections: History". Brooklyn Museum. Archived from the original on 2014-06-24. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ Greenberger, Alex (2018-04-30). "'Brooklyn Is Not for Sale': Decolonize This Place Leads Protest at Brooklyn Museum". ARTnews (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- ^ "'Decolonize This Place' Protesters Disrupt Brooklyn Museum, Condemn 'Imperial Plunder'". Gothamist (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on 2018-08-17. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- ^ أ ب "Collections: History". Brooklyn Museum. Archived from the original on 2014-06-24. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ "Collections: Arts of the Islamic World". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ The Jarvis Collection of Native American Plains Art, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn New York,[2]

- ^ Micucci, Dana (April 19, 2007). "Feminist art gets place of pride in Brooklyn". The New York Times.

- ^ "Archives Collections Index". Brooklyn Museum. Archived from the original on 2014-06-29. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ "Collections: Libraries and Archives". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ "Redesigned and Renovated Brooklyn Museum Libraries and Archives Opens to Public October 20, 2004" (PDF) (Press release). Brooklyn Museum. September 2004. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ "Target First Saturdays at the Brooklyn Museum". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ "Collections: Browse Collections". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ "Brooklyn Museum: ASK". www.brooklynmuseum.org. Retrieved 2017-10-28.

- ^ أ ب ت Pogrebin, Robin (June 14, 2010). "Brooklyn Museum's Populism Hasn't Lured Crowds". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ^ Bell, Jennie. "Arnold Lehman". BlouinArtInfo. blouinartinfo.com. Retrieved 2016-01-12.

- ^ Lehman, Arnold (August 7, 2010). "Response From the Director of the Brooklyn Museum". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

External links

- Official website

- Brooklyn Museum records, 1823-1963 from the Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

- Brooklyn Museum Building Online Exhibition

- The Brooklyn Museum مجموعة في أرشيف الإنترنت

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles using NRISref without a reference number

- Articles with dead external links from January 2016

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Official website different in Wikidata and Wikipedia

- Brooklyn Museum

- 1897 establishments in New York City

- Art museums established in 1897

- Art museums and galleries in New York City

- Buildings and structures completed in 1895

- Beaux-Arts architecture in New York City

- Cultural infrastructure completed in 1897

- Buildings and structures on the National Register of Historic Places in New York City

- Culture of Brooklyn

- Egyptological collections in the United States

- Pre-Columbian art museums in the United States

- Institutions accredited by the American Alliance of Museums

- New York City Designated Landmarks in Brooklyn

- Asian art museums in New York (state)

- McKim, Mead & White buildings

- Museums in Brooklyn

- Museums of American art

- Museums of Ancient Near East

- Crown Heights, Brooklyn

- Prospect Heights, Brooklyn

- National Register of Historic Places in Brooklyn

- Museums on the National Register of Historic Places in New York (state)

- Sculptures by Daniel Chester French

- Sculptures carved by the Piccirilli Brothers

- Allegorical sculptures in New York City

- African art museums in the United States