أون سان

- في هذا الاسم البورمي, Bogyoke لقب فخري.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

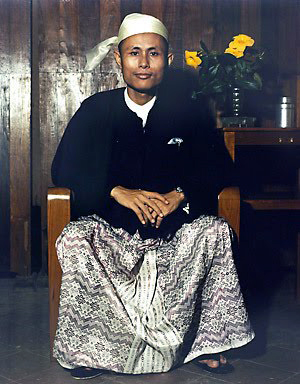

بوگيوكه (الجنرال) أون سان Aung San (بالبورمية: ဗိုလ်ချုပ် အောင်ဆန်း; MLCTS: buil hkyup rki aung hcan:، نطق بورمية: [bòdʑoʊʔ àʊɴ sʰáɴ])؛ (13 فبراير 1915 – 19 يوليو 1947)، هو ثوري، ووطني بورمي، ومؤسس الجيش البورمي الحديث (تاتماداو)، ويعتبر أبو بورما المعاصرة. وهو مؤسس الحزب الشيوعي البورمي.

كان مسئولاً عن الحصول على استقلال بورما من الحكم الاستعماري البريطاني، وأُغتيل قبل ستة أشهر من الاستقلال. وينظر إليه على أنه مهندس استقلال بورما، ومؤسس اتحاد بورما. يشتهر باسم "بوگيوكه" (الجنرال)، ولا يزال محل تقدير الشعب البورمي، ولا يزال اسمه يردد في السياسة البورمية حتى اليوم.

ابنته أون سان سو تشي، سياسية بورمية وحائزة جائزة نوبل للسلام.

حياته

أسماؤه

- اسمه عند الميلاد: Htein Lin (ထိန်လင်း)

- كزعميم للطلبة thakin: أون سان (သခင်အောင်ဆန်း)

- اسم الحرب: Bo Teza (ဗိုလ်တေဇ)

- الاسم الياباني: Omoda Monji (قالب:Jp)

- الاسم الصيني: Tan Lu Sho

- فترة النهضة والاسم الحركي: Myo Aung (မျိုးအောင်), U Naung Cho (ဦးနောင်ချို)

- اسم رمز التواصل مع الجنرال Ne Win: Ko Set Pe (ကိုစက်ဖေ)

النضال من أجل الاستقلال

فترة الحرب العالمية الثانية

تشكيل "الرفاق الثلاثون"

Aung San in Japan (right), with Bo Let Ya (Thakin Hla Pe) (left) and Bo Sekkya (Thakin Aung Than) (middle) |

In May 1940 Japanese intelligence officers led by Suzuki Keiji had arrived in Yangon posing as journalists in order to gather information and to seek the cooperation of local parties for the intended Japanese invasion of Burma, occupying an office at 40 Judah Ezekiel Street for that purpose. Among their network of local collaborators they made close connections with the Thakins, of which Aung San was a leading member. The familiarity of Japanese intelligence with prominent political actors in Burma ensured that they were aware of Aung San's activities by the time he arrived in Japanese-occupied China.[1]

بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية

World War II ended on 12 September 1945. Following the end of the war the Burma National Army was renamed the Patriotic Burmese Forces (PBF), and then gradually disarmed by the British as the Japanese were driven out of various parts of the country.

The leaders of the Patriotic Burmese Forces, while disbanded, were offered positions in the Burma Army under British command according to the Kandy conference agreement with Lord Louis Mountbatten in Ceylon in September 1945. Aung San was not invited to negotiate, since the British Governor General, Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, was debating whether he should be put on trial for his role in the public execution of a Muslim headman in Thaton during the war.[2] The delegates agreed that the new Burmese army would be composed of 5,000 of Aung San's Japanese-trained Bamar soldiers, and 5,000 British-trained soldiers, most of whom were either Chin, Kachin, or Karen.[3] Aung San wrote to U Seinda in Arakan, saying that he supported U Seida's guerrilla fight against the British, but that he would cooperate with them for tactical reasons. After the Kandy Conference, he reorganized his formally disbanded soldiers as a paramilitary organization the People's Volunteer Organization (PVO), which continued to wear uniforms and drill in public. The PVO was personally loyal to Aung San and his party rather than the government. By 1947, the PVO had over 100,000 members.[4] In January 1946 a victory festival was held in the Kachin capital of Myitkyina. Governor Dorman-Smith was invited to attend, but neither Aung San nor anyone from his party were, due to "their connection with the Burma Independence Army".[5]

In an audacious move, Aung San turned himself in for the execution of a village headman. As arresting him would mean a nationwide armed rebellion by the PVO, Dorman-Smith was replaced by a new Governor General of Burma, Sir Hubert Rance. Rance agreed to recognize and negotiate directly with Aung San, possibly to distance them both from the Communist Party of Burma. He also agreed to appoint Aung San to the position of counselor for defense on the Executive Council (a provisional cabinet made in lieu of the upcoming Burmese national election). On 28 September 1946, Aung San was appointed to the even higher position of deputy chairman, making him effectively the 5th Prime Minister of the British-Burma Crown Colony.[6] Aung San had at first worked closely with the Burmese Communist Party, but after they began criticizing him for working with the British he banned all communists from his Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League on 3 November 1946.[7]

اتفاقية آون سان-أتلي ومؤتمر پانگلونگ

Aung San was to all intents and purposes Prime Minister, although he was still subject to a British veto. British Prime Minister Clement Attlee invited Aung San to visit London in 1947 in order to negotiate the conditions of Burmese independence.[8] At a press conference during a stopover in Delhi,[9] while on the way to meet Attlee in London,[7] he stated that the Burmese wanted "complete independence" and not dominion status, and that they had "no inhibitions of any kind" about "contemplating a violent or non-violent struggle or both" in order to achieve it. He concluded that he hoped for the best, but was prepared for the worst.[9] He arrived in Britain by air in January 1947 along with his deputy Tin Tut, who he considered his brightest official. Attlee and Aung San signed their agreement on the terms of Burmese independence on 27 January; following the Burmese election in 1947 Burma would join the British Commonwealth (like Canada and Australia), though its government would have the option to leave, its government would control the Burmese Army once Allied armies had withdrawn, a constitutional assembly would be drawn up as soon as possible, with the resulting constitution presented to the British parliament as soon as possible, and Britain would nominate Burma's entrance into the newly founded United Nations.[8] The agreement was not unanimous: two other delegates who attended the conference, U Saw and Thakin Ba Sein, refused to sign it, and it was denounced in Burma by Aung San's critics, including Than Tun and Thakin Soe. No delegates representing Burma's ethnic minorities were present, and both Karen and Shan leaders sent messages warning that they would not consider any agreement signed at the conference legally binding to their communities.[10]

Two weeks after the signing of the agreement with Britain, Aung San signed an agreement at the second Panglong Conference on 12 February 1947, with leaders representing the Shan, Kachin, and Chin People. In this agreement these leaders agreed to join a united independent Burma, under the condition that they would have "full autonomy"[11] and the right to secede in 1958, after ten years. Karen leaders were not consulted and were not a part of the agreement. They hoped for a separate Karen State within the British Empire.[12] The date of the signing of the Panglong Agreement has been celebrated in Burma as "Union Day", even though Ne Win effectively dissolved any agreement with Burma's minority communities following his coup in 1962.[13][14]

The general election held in April 1947 was not ideal; the Karens,[12] Mon,[15] and most of Aung San's other political opponents boycotted the process. Since they ran virtually unopposed, every delegate in Aung San's party was elected.[12] In the end Aung San's AFPFL won 176 out of the 210 seats in the Constituent Assembly, while the Karens won 24, the Communists 6, and the Anglo-Burmans 4.[16] In July, Aung San convened a series of conferences at Sorrenta Villa in Rangoon to discuss the rehabilitation of Burma.

Following the 1947 election Aung San began to form his own cabinet. In addition to ethnic Burmese statesmen like himself and Tin Tut, he also persuaded the Karen leader Mahn Ba Khaing, the Shan Chief Sao Hsam Htun, and the Tamil Muslim leader Abdul Razak to join his cabinet. No Communists were invited to participate.[17]

اغتياله

العائلة

ذكراه

المصادر

- ^ Thant 219

- ^ Smith 65-66

- ^ Thant 244-245

- ^ Smith 66

- ^ Smith 73

- ^ Smith 69

- ^ أ ب Lintner 2003 80

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةThant 252 - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةas - ^ Smith 77-78

- ^ Smith 78

- ^ أ ب ت Thant 253

- ^ Smith 79

- ^ "The Panglong Agreement, 1947". Online Burma/Myanmar Library.

- ^ South 26

- ^ Appleton, G. (1947). "Burma Two Years After Liberation". International Affairs. Blackwell Publishing. 23 (4): 510–521. JSTOR 3016561.

- ^ Thant 254

وصلات خارجية

- Aung San's resolution to the Constituent Assembly regarding the Burmese Constitution, 16 June 1947

- Who really killed Aung San? Vol 1 at YouTube BBC documentary on YouTube, 19 July 1997

- Kin Oung. Eliminate the Elite - Assassination of Burma's General Aung San & his six cabinet colleagues. Uni of NSW Press. Special edition - Australia 2011. ISBN 978-0-046-55497-6

- http://www.bogyokeaungsanmovie.org/

- Articles containing بورمية-language text

- ثوريون بورميون

- جنرالات بورميون

- سياسيون بورميون مغتالون

- بورميون متعانون من امبراطورية اليابان

- وفيات بإطلاق النار في بورما

- مواليد 1915

- وفيات 1947

- مقتولون في بورما

- خريجو جامعة يانگون

- سياسيو الحزب الشيوعي البورمي

- سياسيو عصبة حرية الشعب المناهضة للفاشية

- وزراء حكومة بورما

- دولة بورما

- شهداء ثوريون