پاتاليپوترا

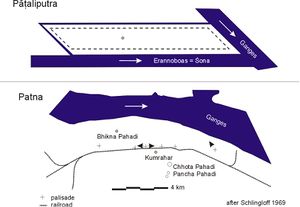

Plan of Pataliputra compared to present-day Patna | |

| الاسم البديل | Pātaliputtā (Pāli) |

|---|---|

| المكان | Patna district, Bihar, India |

| المنطقة | South Asia |

| الإحداثيات | 25°36′45″N 85°7′42″E / 25.61250°N 85.12833°E |

| الارتفاع | 53 m (174 ft) |

| الطول | 14.5 km (9.0 mi) |

| العرض | 2.4 km (1.5 mi) |

| التاريخ | |

| الباني | Ajatashatru |

| تأسس | 490 BCE |

| هـُـجـِر | Became modern Patna |

| مقترن بـ | Haryankas, Nandas, Mauryans, Shungas, Guptas, Palas, Sher Shah Suri |

| الادارة | Archaeological Survey of India |

پاتاليپوترا (Pataliputra ؛ IAST: Pāṭaliputra), adjacent to modern-day Patna, was a city in ancient India, originally built by Magadha ruler Udayin in 490 BCE as a small fort (Pāṭaligrāma) near the Ganges river.[1]

| الحج إلى الأماكن المقدسة البوذية |

|

| الأماكن الأربعة المقدسة الرئيسية |

|---|

| لومبيني · Bodh Gaya Sarnath · كوشينگر |

| الأماكن الأربعة الإضافية |

| Sravasti · راجگير سانكيسا · ڤايشالي |

| أماكن أخرى |

| پاتاليپوترا · گايا · كوسامبي Kapilavastu · Devadaha Kesariya · پاڤا نالندا · ڤرناسي |

| مواقع لاحقة |

| Sanchi · متهرا إلورا · أجانتا · Vikramshila راتناگيري · أوداياگيري · لاليتگيري بهارهوت · كهوف بارابار |

وقد أصبحت عاصمة قوى كبرى في الهند القديمة، مثل امبراطورية ناندا (345-320 ق.م.)، وامبراطورية موريا (320-180 ق.م.) وامبراطورية گوپتا (320-550 م). وفي عهد موريا (انظر أدناه)، أصبحت واحدة من أكبر المدن في العالم.

Extensive archaeological excavations have been made in the vicinity of modern Patna.[2][3] Excavations early in the 20th century around Patna revealed clear evidence of large fortification walls, including reinforcing wooden trusses.[4][5]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

أصل الاسم

The etymology of Pataliputra is unclear. "Putra" means son, and "pāţali" is a species of rice or the plant Bignonia suaveolens.[6] One traditional etymology[7] holds that the city was named after the plant.[8] Another tradition says that Pāṭaliputra means the son of Pāṭali, who was the daughter of Raja Sudarshan.[9] As it was known as Pāṭali-grāma ("Pāṭali village") originally, some scholars believe that Pāṭaliputra is a transformation of Pāṭalipura, "Pāṭali town".[10]

التاريخ

There is no mention of Pataliputra in written sources prior to the early Buddhist texts (the Pali Canon and Āgamas), where it appears as the village of Pataligrama and is omitted from a list of major cities in the region.[11]تتكلم المصادر البوذية المبكرة عن مدينة بُنيت بالقرب من القرية في آخر عمر بوذا؛ وهذا يتفق عموماً مع الأدلة الأثرية التي تُظهر تطوراً حضرياً حدث في المنطقة ليس قبل القرن الثالث أو الرابع ق.م..[11] In 303 BCE, Greek historian and ambassador Megasthenes mentioned Pataliputra as a city in his work Indika.[12]

The city of Pataliputra was formed by fortification of a village by Haryanka ruler Ajatashatru, son of Bimbisara.[13]

موقعها المركزي في شمال شرق الهند دفع حكام أسر متتالية لأن يتخذوا منها عاصمة ادارية، من أسرات ناندا، موريا، وشونگا وگوپتا وحتى پالا.[14][صفحة مطلوبة] Situated at the confluence of the Ganges, Gandhaka and Son rivers, Pataliputra formed a "water fort, or jaldurga".[15] Its position helped it dominate the riverine trade of the Indo-Gangetic plains during Magadha's early imperial period. It was a great centre of trade and commerce and attracted merchants and intellectuals, such as the famed Chanakya, from all over India.

Two important early Buddhist councils are recorded in early Buddhist texts as being held here, the First Buddhist council immediately following the death of the Buddha and the Second Buddhist council in the reign of Ashoka. Jain and Brahmanical sources identify Udayabhadra, son of Ajatashatru, as the king who first established Pataliputra as the capital of Magadha.[11]

عاصمة امبراطورية موريا

During the reign of Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE, it was one of the world's largest cities, with a population of 150,000–400,000.[16] The city is estimated to have had a surface of 25.5 square kilometers, and a circumference of 33.8 kilometers, and was in the shape of a parallelogram and had 64 gates (that is, approximately one gate every 500 meters).[17] Pataliputra reached the pinnacle of prosperity when it was the capital of the great Mauryan Emperors, Chandragupta Maurya and Ashoka. The city prospered under the Mauryas and a Greek ambassador, Megasthenes, resided there and left a detailed account of its splendour, referring to it as "Palibothra":

"Megasthenes says that on one side where it is longest this city extends ten miles in length, and that its breadth is one and threequarters miles; that the city has been surrounded with a ditch in breadth 600 feet, and in depth 45 feet; and that its wall has 570 towers and 64 gates." Arrian, "The Indica"[18]

Strabo in his Geographia adds that the city walls were made of wood. These are thought to be the wooden palisades identified during the excavation of Patna.[19]

"At the confluence of the Ganges and of another river is situated Palibothra, in length 80, and in breadth 15 stadia. It is in the shape of a parallelogram, surrounded by a wooden wall pierced with openings through which arrows may be discharged. In front is a ditch, which serves the purpose of defence and of a sewer for the city." Strabo, "Geographia"[20]

Aelian, although not expressly quoting Megasthenes nor mentionning Pataliputra, described Indian palaces as superior in splendor to Persia's Susa or Ectabana:

"In the royal residences in India where the greatest of the kings of that country live, there are so many objects for admiration that neither Memnon's city of Susa with all its extravagance, nor the magnificence of Ectabana is to be compared with them. (...) In the parks, tame peacocks and pheasants are kept." Aelian, "Characteristics of animals"[21]

Under Ashoka, most of wooden structure of Pataliputra palace may have been gradually replaced by stone.[22] Ashoka was known to be a great builder, who may have even imported craftsmen from abroad to build royal monuments.[23] Pataliputra palace shows decorative influences of the Achaemenid palaces and Persepolis and may have used the help of foreign craftmen.[24] Which may be the result of the formative influence of craftsmen employed from Persia following the disintegration of the Achaemenid Empire after the conquests of Alexander the Great.[25][26]

عاصمة الأسر اللاحقة

The city also became a flourishing Buddhist centre boasting a number of important monasteries. It remained the capital of the Gupta dynasty (3rd–6th centuries) and the Pala Dynasty (8th-12th centuries). The city was largely in ruins when visited by Xuanzang, and suffered further damage at the hands of Muslim raiders in the 12th century.[27] Afterwards, Sher Shah Suri made Pataliputra his capital and changed the name to modern Patna.

Structure

Though parts of the ancient city have been excavated, much of it still lies buried beneath modern Patna. Various locations have been excavated, including Kumhrar, and Bulandi Bagh.

During the Mauryan period, the city was described as being shaped as parallelogram, approximately 1.5 miles wide and 9 miles long. Its wooden walls were pierced by 64 gates. Archaeological research has found remaining portions of the wooden palisade over several kilometers, but stone fortifications have not been found.[28]

مواقع الحفريات في پاتاليپوترا

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

معرض الصور

Pataliputra as a capital of the Haryanka dynasty of the Magadha Empire.

Pataliputra as a capital of Maurya Empire.

The Maurya Empire at its largest extent under Chandragupta Maurya and Bindusara.Pataliputra as a capital of Shunga Empire.

Approximate greatest extent of the Shunga Empire (c. 185 BCE).Pataliputra as a capital of Gupta Empire.

Approximate greatest extent of the Gupta Empire.Pataliputra as a capital of Sher Shah's Empire.

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004), A History of India, 4th edition. Routledge, Pp. xii, 448, ISBN 0-415-32920-5, https://www.amazon.com/History-India-Hermann-Kulke/dp/0415329205/.

- ^ "Patna". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 13 Dec. 2013 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/446536/Patna>.

- ^ "Heritage wall for Metro corridor plan".

- ^ "A relic of Mauryan era".

- ^ Valerie Hansen Voyages in World History, Volume 1 to 1600, 2e, Volume 1 pp. 69 Cengage Learning, 2012

- ^ Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Pāṭali, [1] (a junior synonym of Stereospermum colais [2])

- ^ Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, p.677

- ^ Folklore, Vol. 19, No. 3 (30 September 1908), pp. 349–350

- ^ The Calcutta Review Vol LXXVI (1883), p.218

- ^ Language, Vol. 4, No. 2 (June , 1928), pp. 101–105

- ^ أ ب ت Sujato, Bhikkhu; Bhikkhu, Brahmali, The Authenticity of the Early Buddhist Texts, Oxford Center for Buddhist Studies, Archived from the original on 20 November 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20171120102236/https://ocbs.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/authenticity.pdf.

- ^ Tripathi, Piyush Kumar (16 July 2015). "Realty to broaden horizon". The Telegraph. Calcutta.

- ^ Sastri 1988, p. 11.

- ^ Thapar, Romilak (1990), A History of India, Volume 1, New Delhi and London: Penguin Books. Pp. 384, ISBN 0-14-013835-8.

- ^ The Pearson Indian History Manual, Pearson Education India, A94.

- ^ The Rise of Man in the Gardens of Sumeria: A Biography of L.A. Waddell, Christine Preston, Sussex Academic Press, 2009, p.49 [3]

- ^ Fortified Cities of Ancient India: A Comparative Study, Dieter Schlingloff, Anthem Press, 2014, p.49 [4]

- ^ Arrian, "The Indica" Archived 25 مايو 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kosmin 2014, p. 42.

- ^ Strabo Geographia Vol 3 Paragraph 36

- ^ Aelian, Characteristics of animals, book XIII, Chapter 18, also quoted in The Cambridge History of India, Volume 1, p411

- ^ Asoka Mookerji Radhakumud, Motilal Banarsidass Publishing, 1995 p.96 [5]

- ^ Monuments, Power and Poverty in India: From Ashoka to the Raj, A. S. Bhalla, I.B.Tauris, 2015 p.18 [6]

- ^ The Analysis of Indian Muria Empire affected from Achaemenid’s architecture art. In: Journal of Subcontinent Researches. Article 8, Volume 6, Issue 19, Summer 2014, Page 149-174.

- ^ "The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c.6500 BCE-200 CE" Robin Coningham, Ruth Young Cambridge University Press, 31 aout 2015, p.414 [7]

- ^ Report on the excavations at Pātaliputra (Patna); the Palibothra of the Greeks by Waddell, L. A. (Laurence Austine)

- ^ Scott, David (May 1995). "Buddhism and Islam: Past to Present Encounters and Interfaith Lessons". Numen. 42 (2): 141–155. doi:10.1163/1568527952598657. JSTOR 32701721.

- ^ Excavation sites in Bihar, Archaeological Survey of India, http://www.asi.nic.in/asi_exca_imp_bihar.asp, retrieved on 13 September 2009.

المصادر

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014), The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0, https://books.google.com/books?id=9UWdAwAAQBAJ

- Sastri, Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta, ed. (1988), Age of the Nandas and Mauryas (Second ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0465-1, https://books.google.com/books?id=YoAwor58utYC

للاستزادة

- Bernstein, Richard (2001). Ultimate Journey: Retracing the Path of an Ancient Buddhist Monk (Xuanzang) who crossed Asia in Search of Enlightenment. Alfred A. Knopf, New York. ISBN 0-375-40009-5