يارلونگ تسانگپو، الخندق العظيم

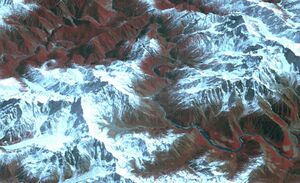

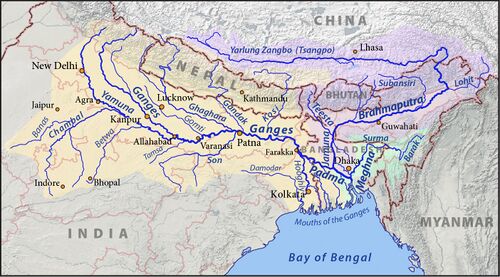

The Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, also known as the Yarlung Zangbo Grand Canyon, the Tsangpo Canyon, the Brahmaputra Canyon or the Tsangpo Gorge (simplified Chinese: 雅鲁藏布大峡谷; traditional Chinese: 雅魯藏布大峽谷; pinyin: Yǎlǔzàngbù Dàxiágǔ'), is a canyon along the Yarlung Tsangpo River in Tibet Autonomous Region, China. It is the deepest canyon in the world,[1][أ] and at 504.6 kilometres (313.5 mi) is slightly longer than the Grand Canyon in the United States, making it one of the world's largest.[1][3] The Yarlung Tsangpo (Tibetan name for the upper course of the Brahmaputra) originates near Mount Kailash and runs east for about 1,700 kilometres (1,100 mi), draining a northern section of the Himalayas before it enters the gorge just downstream of Pei, Tibet, near the settlement of Zhibe. The canyon has a length of about 240 kilometres (150 mi) as the gorge bends around Mount Namcha Barwa (7,782 metres or 25,531 feet) and cuts its way through the eastern Himalayas. Its waters drop from about 2,900 metres (9,500 ft) near Pei to about 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) at the end of the Upper Gorge where the Po Tsangpo River enters. The river continues through the Lower Gorge to the Indian border at an elevation of 660 metres (2,170 ft). The river then enters Arunachal Pradesh and eventually becomes the Brahmaputra.[4][5]

عمق الخندق

As the canyon passes between the peaks of the Namcha Barwa (Namjabarwa) and Gyala Peri mountains, it reaches an average depth of about 5,000 m (16,000 feet) around Namcha Barwa. The canyon's average depth overall is about 2,268 m (7,440 feet), the deepest depth reaches 6,009 m (19,714 feet). This is the greatest canyon depth on land.[بحاجة لمصدر] This part of the canyon is at 29°46′11″N 94°59′23″E / 29.769742°N 94.989853°E. Namcha Barwa, 7,782 m (25,531 feet) high, is at 29°37′33″N 95°03′26″E / 29.62583°N 95.05722°E, and Gyala Peri, at 7,234 m (23,733 feet), is at 29°48′48″N 94°58′02″E / 29.81333°N 94.96722°E.[6]

Ecosystem

The gorge has a unique ecosystem with species of animals and plants barely explored and affected by human influence. Its climate ranges from subtropical to Arctic, and it has several different vegetation zones: Lowland tropical forests, including the [tropical rainforest]] and seasonal tropical forests; tropical montane and subtropical broad-leaved forest; subalpine temperate coniferous forest; subalpine cool coniferous forest; alpine shrubland and tundra. The highest temperature in Tibet is 43.6 °C (110.5 °F) and is recorded near the border of India at about 600 metres (2,000 ft) above sea level. The rare takin is one of the animals hunted by the local tribes.

The canyon is home of a Himalayan cypress (Cupressus torulosa) that is 102.3 metres (336 ft) tall and, upon its discovery in 2023, is believed to be the tallest tree in Asia.[7][8]

إڤرست الأنهار

Western interest in the Tsangpo began in the 19th century when British explorers and geographers speculated where Tibet's east-flowing Tsangpo ended up, suspecting the Brahmaputra. Since British citizens were not allowed to enter Tibet they recruited Indian "pundits" to do the footwork. Kinthup from Sikkim entered the gorge near Gyala, but it proved to be impenetrable. In 1880 Kinthup was sent back to test the Brahmaputra theory by releasing 500 specially marked logs into the river at a prearranged time. His British boss Captain Henry Harman posted men on the Dihang-Brahmaputra to watch for their arrival. However, Kinthup was sold into slavery, escaped, and ended up employed at a monastery. On three leaves of absence he managed to craft the logs, send a letter from Lhasa with his new intended schedule, and send off the logs. Four years had passed. Unfortunately his note to alert the British got misdirected, his boss had left India, and nobody checked for the appearance of the logs.[9]

In 1913, Frederick Marshman Bailey and Henry Morshead launched an expedition into the gorge that finally confirmed that the Tsangpo was indeed the upper Brahmaputra. Frank Kingdon-Ward started an expedition in 1924 in hopes of finding a major waterfall explaining the difference in altitude between the Tsangpo and the Brahmaputra. It turned out that the gorge has a series of relatively steep sections. Among them was a waterfall he named "Rainbow Falls", not as big as he had hoped.

The area was closed after China invaded Tibet and disputed the location of the border in the Sino-Indian War. The Chinese government resumed issuing permits in the 1990s. Since then the gorge has also been visited by kayakers. It has been called the "Everest of Rivers" because of the extreme conditions.[10] The first attempt was made in 1993 by a Japanese group who lost one member on the river. In October 1998 an expedition sponsored by the National Geographic Society attempted to kayak the entire gorge. Troubled by unanticipated high water levels, it ended in tragedy when Doug Gordon was lost.[11] In January–February 2002 an international group with Scott Lindgren, Steve Fisher, Mike Abbott, Allan Ellard, Dustin Knapp, and Johnnie and Willie Kern completed the first full descent of the upper Tsangpo gorge section.[12][13]

The largest waterfalls of the gorge (near Tsangpo Badong, Chinese: 藏布巴东瀑布群[14]) were visited in 1998, by a team consisting of Ken Storm, Hamid Sarder, Ian Baker and their Monpa guides.[15] They estimated the height of the falls to be about 33 metres (108 ft). The falls and rest of the Pemako area are sacred to Tibetan Buddhists who had concealed them from outsiders including the Chinese authorities.[16] In 2005 Chinese National Geography named them China's most beautiful waterfalls.

There are two waterfalls in this section: Rainbow Falls (about 21 metres or 70 feet high) at 29°46′38″N 95°11′00″E / 29.777164°N 95.183406°E and Hidden Falls just downstream at 29°46′34″N 95°10′55″E / 29.776023°N 95.181974°E (about 30 metres or 100 feet high).[6][17]

Yarlung Tsangpo Hydroelectric and Water Diversion Project

While the government of the PRC has declared the establishment of a "Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon National Reservation", there have also been governmental plans and feasibility studies for a major dam to harness hydroelectric power and divert water to other areas in China.[بحاجة لمصدر] The size of the dam in the Tsongpo gorge would exceed that of Three Gorges Dam as it is anticipated that such a plant would generate 50,000 megawatts[18] of electricity, more than twice the output of Three Gorges. It is feared that there will be displacement of local populations, destruction of ecosystems, and an impact for downstream people in India and Bangladesh.[19] The project is criticized by India because of its potential negative impact upon the residents downstream.[20]

In 1999, R.B. Cathcart suggested that a fabric dam—inflatable with freshwater or air—could block the Yarlung Tsangpo Canyon upstream of Namcha Barwa. Water would then be conveyed via a hard rock tunnel to a point downstream from that mountain.[21]

Steel dams are more advantageous and economical in remote hilly terrain at high altitude for diverting the run off water of the river to power generating units.[22]

References in media

- The gorges may have helped inspire the idea of Shangri-La in James Hilton's book Lost Horizon in 1933.[23]

- In the 2007 fighting game Akatsuki Blitzkampf, the biggest base and research facility of the villainous organization Gessellschaft is hidden in the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, referred to in-story as the "Tsangpo Ravine". The second part of the game takes place in said base, with the player fighting their way inside it until they reach the last enemy.

See also

- Nyingchi

- Zangmu Dam

- South–North Water Transfer Project

- Inga dams

- Bailey–Morshead exploration of Tsangpo Gorge

Notes

References

- ^ أ ب Canyon, National Geographic Encyclopedic Entry, retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Andrea Thompson, What's the Deepest Canyon?, livescience.com, 14 January 2013.

- ^ "The length, depth and slope-deflection of the great canyon are all the mosts of the world". www.kepu.net.cn. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Yang Qinye and Zheng Du (2004). Tibetan Geography. China Intercontinental Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-7-5085-0665-4.

- ^ Zheng Du, Zhang Qingsong, Wu Shaohong: Mountain Geoecology and Sustainable Development of the Tibetan Plateau (Kluwer 2000), ISBN 0-7923-6688-3, p. 312;

- ^ أ ب "First Descent of the Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibet". www.shangri-la-river-expeditions.com. Archived from the original on 12 September 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ "Tallest tree of Asia found in Tibet". China Daily. 27 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ Lydia Smith (June 21, 2023). "World's deepest canyon is home to Asia's tallest tree - and Chinese scientists only just found it". LiveScience. Retrieved June 24, 2023. Claim in article that it is second tallest tree in the world is consistent with sloppy reading of Wikipedia's List of tallest trees as of June 21, 2023, but is apparently false: an earlier LiveScience article in 2022 reports on heights of three taller coastal redwood trees in the United States: Hyperion, Helios, and Icarus (third tallest, at 113.1 metres (371 ft), as measured in 2006).

- ^ Allen, Charles (1982). A Mountain in Tibet: The Search for Mount Kailas and the Sources of the Great Rivers of Asia. London: David & Charles. ISBN 9780233972817.

- ^ "The Outside Tsangpo expedition triumphs on "The Everest of Rivers" — Tibet's legendary Tsangpo" (Press release). New York, NY: Outside Online. 2 April 2002. Archived from the original on 12 August 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Walker, Wickliffe W. (September 2000). Courting the Diamond Sow: A Whitewater Expedition on Tibet's Forbidden River. National Geographic. ISBN 978-0-7922-7960-0.

- ^ Heller, Peter (28 June 2004). "Liquid Thunder". Outside. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Winn, Peter S. (5 June 2011). "First Descents of the Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibet". Archived from the original on 2021-12-12. Retrieved 23 April 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Yarlung Tsangpo Waterfall". Archived from the original on 2009-08-12. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- ^ "Fabled Tibetan waterfalls finally discovered". Tibet.ca. Canada Tibet Committee. 7 January 1999. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Baker, Ian (2004). The Heart of the World. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-5942-0027-4.

- ^ The falls can be seen more clearly in an IKONOS imageArchived 2011-10-05 at the Wayback Machine from here Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine taken May 9, 2000, which is oriented with south up.

- ^ Yong, Yang (3 May 2014). "World's largest hydropower project planned for Tibetan Plateau". ChinaDialogue.net (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2017-12-30.

- ^ Tsering, Tashi (2002). An Analysis of China's Water Management and Politics. Tibet Justice Center. p. 21. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://www.tibetjustice.org/reports/enviro/hydrologic.pdf. Retrieved on 23 April 2018. - ^ "Let the Brahmaputra Flow". Trin-gyi-pho-nya. No. 4. Tibet Justice Center. 12 January 2004. Archived from the original on 8 November 2004. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Cathcart, Richard Brook (10 October 1999). "Tibetian power : A unique hydro-electric macroproject servicing India and China" (PDF). Current Science. 77 (7): 854–855. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Reynolds, Terry S. (1989). "A Narrow Window of Opportunity: The Rise and Fall of the Fixed Steel Dams". The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology. 15 (1): 1–20. JSTOR 40968160.

- ^ "Yarlung Tsangpo River in China". NASA.gov. Archived from the original on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

Further reading

- Wick Walker (2000). Courting the Diamond Sow : A Whitewater Expedition on Tibet's Forbidden River. National Geographic. ISBN 0-7922-7960-3.

- Todd Balf (2001). The Last River : The Tragic Race for Shangri-la. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-609-80801-X.

- Michael Mcrae (2002). The Siege of Shangri-La : The Quest for Tibet's Sacred Hidden Paradise. Broadway. ISBN 0-7679-0485-0. ISBN 978-0-7679-0485-8.

- Peter Heller (2004). Hell or High Water : Surviving Tibet's Tsangpo River. Rodale Books. ISBN 1-57954-872-5.

- Ian Baker (2004). The Heart of the World : A journey to the last secret place. Souvenir Press. ISBN 0-285-63742-8.

- F.Kingdon Ward (Author), Kenneth Cox (Editor), Ken Storm Jr (Editor), Ian Baker (Editor) Riddle of the Tsangpo Gorges: Retracing the Epic Journey of 1924–25 in South-East Tibet (Hardcover) Antique Collectors' Club Ltd (1 Jan 1999) ISBN 1-85149-371-9

Videos

- Scott Lindgren (2002), "Into the Tsangpo Gorge". Slproductions. ASIN B0006FKL2Q.

- Into the Tsangpo Gorge Documentary

External links

Media related to Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon at Wikimedia Commons- Into the Tsangpo Gorge (Outside Online)

- IKONOS Satellite Image of "Rainbow Falls" and "Hidden Falls"

- Douglas Gordon at University of Utah

- Touristic information

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value). 29°36′43″N 94°56′10″E / 29.612°N 94.936°E

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing simplified Chinese-language text

- Articles containing traditional Chinese-language text

- قوائم إحداثيات

- Geographic coordinate lists

- Articles with Geo

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2015

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Canyons and gorges of China

- Rivers of Tibet

- Landforms of Tibet

- Extreme points of Asia