الإنسان الماهر

| الإنسان الماهر Homo habilis | |

|---|---|

| |

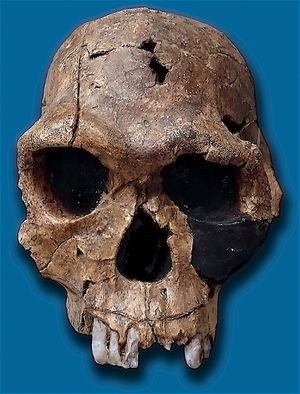

| إعادة بناء KNM-ER 1813 في متحف الطبيعة، زنكنبرگ، ألمانيا | |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| مملكة: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | H. habilis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Homo habilis ليكي ورفاقه، 1964

| |

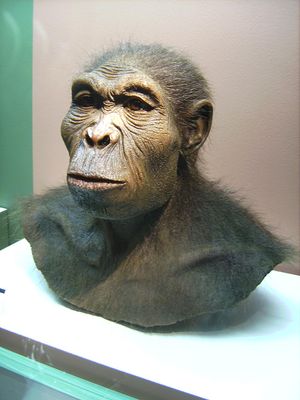

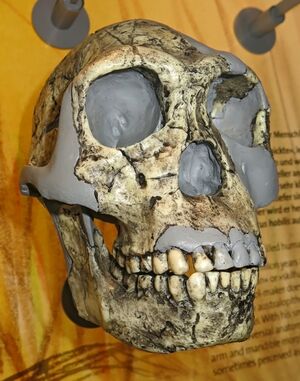

الإنسان الحاذق أو الإنسان الماهر Homo habilis (هومو هابيلس)، هو نوع من جنس هومو، عاش في مناطق شرق القارة الإفريقية ما بين (2.5 و 1.6) مليون سنة مضت، في مطلع العصر الپلايستوسين. ويعود فضل اكتشاف ووصف هذا النوع إلى ماري ولويس ليكي، الذين اكتشفوا أول أحافيره في شمال تنزانيا بين 1962 و1964.[1] Homo habilis (أو من المحتمل هـ. رودولفنسيس) كان أقدم نوع معروف من جنس هومو حتى مايو 2010، عندما اُكتـُشِف هـ. گاوتنگنسيس H. gautengensis، النوع الذي يُعتقد أنه أقدم حتى من هـ. هابيليس.[2] وفي مظهره وشكله، فإن هـ. هابيليس هو بذلك الأقل شبهاً للبشر الحاليين بين كل أنواع جنس هومو (مع استثناء محتمل لـهومو رودولفنسيس). الإنسان الماهر كان قصيراً وذراعاه طويلتان دون تناسب بالمقارنة مع البشر الحاليين؛ إلا أن وجهه كان أقل بروزاً من وجه أنواع أسترالوپثيكس التي يُعتقد أنها انحدرت منها. وكان لـهـ. هابيليس سعة دماغية أقل قليلاً من نصف نظيرتها في البشر الحاليين. وبالرغم من الشكل الشبيه بالقردة العليا في الجسد، فإن بقايا هـ. هابيليس كثيراً ما يصاحبها أدوات حجرية بدائية (كما في Olduvai Gorge، تنزانيا وبحيرة تركانا, كنيا).

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التصنيف

تاريخ البحث

The first recognised remains—OH 7, partial juvenile skull, hand, and foot bones dating to 1.75 million years ago (mya)—were discovered in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, in 1960 by Jonathan Leakey. However, the actual first remains—OH 4, a molar—were discovered by the senior assistant of Louis and Mary Leakey (Jonathan's parents), Heselon Mukiri, in 1959, but this was not realised at the time.[3] By this time, Louis and Mary had spent 29 years excavating in Olduvai Gorge for early hominin remains, but had instead recovered mainly other animal remains as well as the Oldowan stone tool industry. The industry had been ascribed to Paranthropus boisei (at the time "Zinjanthropus") in 1959 as it was the first and only hominin recovered in the area, but this was revised upon OH 7's discovery.[3] In 1964, Louis, South African palaeoanthropologist Phillip V. Tobias, and British primatologist John R. Napier officially assigned the remains into the genus Homo as, on recommendation by Australian anthropologist Raymond Dart, H. habilis, the specific name meaning "able, handy, mentally skillful, vigorous" in Latin.[4] The specimen's association with the Oldowan (then considered evidence of advanced cognitive ability) was also used as justification for classifying it into Homo.[5] OH 7 was designated the holotype specimen.[4]

After description, it was hotly debated if H. habilis should be reclassified into Australopithecus africanus (the only other early hominin known at the time), in part because the remains were so old and at the time Homo was presumed to have evolved in Asia (with the australopithecines having no living descendants). Also, the brain size was smaller than what Wilfrid Le Gros Clark proposed in 1955 when considering Homo.[6][3] The classification H. habilis began to receive wider acceptance as more fossil elements and species were unearthed.[3] In 1983, Tobias proposed that A. africanus was a direct ancestor of Paranthropus and Homo (the two were sister taxa), and that A. africanus evolved into H. habilis which evolved into H. erectus which evolved into modern humans (by a process of cladogenesis). He further said that there was a major evolutionary leap between A. africanus and H. habilis, and thereupon human evolution progressed gradually because H. habilis brain size had nearly doubled compared to australopithecine predecessors.[7] However, OH 24, at the time the oldest H. habilis specimen, was similar to the younger OH 13, which showed there was no evolutionary progression through the lineage.[6]

Many had accepted Tobias' model and assigned Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene hominin remains outside the range of Paranthropus and H. erectus into H. habilis. For non-skull elements, this was done on the basis of size as there was a lack of clear diagnostic characteristics.[8] Because of these practices, the range of variation for the species became quite wide, and the terms H. habilis sensu stricto ("in the strict sense") and H. habilis sensu lato ("in the broad sense") were in use to include and exclude, respectively, more discrepant morphs. To address this, in 1985, English palaeoanthropologist Bernard Wood proposed that the comparatively massive skull KNM-ER 1470 from Lake Turkana, Kenya, discovered in 1972 and assigned to H. habilis, actually represented a different species,[9] now referred to as Homo rudolfensis. It is also argued that instead it represents a male specimen whereas other H. habilis specimens are female.[10] It has been suggested that early Homo from South Africa can be variously assigned to H. habilis or H. ergaster / H. erectus, but in 2010, Australian archaeologist Darren Curoe proposed splitting off South African early Homo into a new species, Homo gautengensis.[11]

In 1986, OH 62, a fragmentary skeleton, was discovered by American anthropologist Tim D. White in association with H. habilis skull fragments, definitively establishing aspects of H. habilis skeletal anatomy for the first time, and revealing more Australopithecus-like than Homo-like features.[8] Because of this, as well as similarities in dental adaptations, Wood and biological anthropologist Mark Collard suggested moving the species to Australopithecus in 1999.[12][13][14][15] However, reevaluation of OH 62 to a more humanlike physiology, if correct, would cast doubt on this.[16] The discovery of the 1.8 Ma Georgian Dmanisi skulls in the early 2000s, which exhibit several similarities with early Homo, has led to suggestions that all contemporary groups of early Homo in Africa, including H. habilis and H. rudolfensis, are the same species and should be assigned to H. erectus.[17][18]

التصنيف

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Homo family tree showing H. habilis and H. rudolfensis at the base as offshoots of the human line[19] |

There is still no wide consensus as to whether or not H. habilis is ancestral to H. ergaster / H. erectus or is an offshoot of the human line,[20] and whether or not all specimens assigned to H. habilis are correctly assigned or the species is an assemblage of different Australopithecus and Homo species.[21] Nonetheless, H. habilis and H. rudolfensis generally are recognised members of the genus at the base of the family tree, with arguments for synonymisation or removal from the genus not widely adopted.[22]

Though it is now largely agreed upon that Homo evolved from Australopithecus, the timing and placement of this split has been much debated, with many Australopithecus species having been proposed as the ancestor. The discovery of LD 350-1, the oldest Homo specimen, dating to 2.8 mya, in the Afar Region of Ethiopia may indicate that the genus evolved from A. afarensis around this time. The species LD 350-1 belongs to could be the ancestor of H. habilis, but this is unclear.[23] The oldest H. habilis specimen, A.L. 666-1, dates to 2.3 mya, but is anatomically more derived (has less ancestral, or basal, traits) than the younger OH 7, suggesting derived and basal morphs lived concurrently, and that the H. habilis lineage began before 2.3 mya.[24] Based on 2.1 million year old stone tools from Shangchen, China, H. habilis or an ancestral species may have dispersed across Asia.[25] The youngest H. habilis specimen, OH 13, dates to about 1.65 mya.[24]

صفاته

صاحب الجسم القصير ذو اليدين الطويلتين يتميز عن باقي أنواع الإنسان بكبر حجم دماغه الذي يصل إلى 630 سم³ وبأسنانه الصغيرة. تميز أيضاً بقدرة بدائية على استخدام الأدوات. عايش أنواعًا أخرى من أشباه البشر، ويعتبر هو أبو الإنسان المعاصر.

سلوكه

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

المشي على القدمين

الإنسان الماهر كان يتقن المشي على قدمين، ولكننا نجد بالمقابل بأن قصر أعضائه السفلية لم تكن تعطيه نفس قدرة الإنسان العامل على المشي مطولاً، فيبقى مظهره أكثر قدماً من الأخير. هذا النوع من الإنسان يظهر اختلافاً واضحاً بين الجنسين، إذ أن قائمة الأنثى أقصر بكثير من قامة الذكر.

الغذاء

لقد كافح الإنسان الماهر من أجل البقاء، إذ ليس لديه فك قوي ولا أسنان كبيرة يمكنها طحن النباتات التي كانت سائدة في نهاية عصر الجفاف ذلك، ومن أجل أن يتدبر أموره لجأ إلى حل مختلف تماماً فأصبح يبحث عن طعامه في كل مكان وصار مستعداً ليقوم بأي شيء للبقاء! إنها حياة صعبة فطعام الإنسان الماهر قد يكون في أي مكان، وحتى تعثر عليه، يجب أن تكون مستكشفاً لا يكل ولا يمل. لكن أسلوبه الفضولي في الحياة علمه بعض الحيل المفيدة، فإذا كنت فضولياً فربما تكتشف بعض الأسرار مثل السبب الذي تتجمع من أجله النسور في السماء. تغذى الإنسان الماهر على الحشرات واللحوم وبقايا الفرائس التي تصطادها الحيوانات المفترسة الأخرى. وفي الوقت الذي شحت فيه مصادر الغذاء السهلة كالثمار والفواكه، وانقرضت أنواع أخرى اضطر هو لاستخدام مهاراته في البحث عن مصادر جديدة. اللحم ساعدهم ليصبحوا أذكى، فرغم أن الجيف التي يصلون إليها تكون قد جردت من اللحم تماماً، لكن هناك وجبة أخيرة تبقى محفوظة للإنسان الماهر. إنها نقي العظام، أحد أغنى الوجبات من حيث القيمة الغذائية، وهي بعيدة عن متناول الأسود والنسور وبقية المنافسين الذين يستعصي عليهم العظم، أما أدوات الإنسان الماهر فتمكنه من كسر العظم للوصول إلى النخاع الثمين.

استخدام الحجر

الإنسان الماهر عاصر أول الصناعات الحجرية على وجه الأرض، وتمكن من اتقانها، وهي قفزة تطورية كبرى، فالأدوات الحجرية توسع نطاق أنواع الطعام التي يمكنه تناولها، كما ساهم تناول البروتين والدهون الأساسية في تمكين دماغه من التطور. وفي الواقع فإن دماغ الإنسان الماهر أكبر مرة ونصف من دماغ پارانثروپوس بويزي الذي كان يعيش في نفس الحقبة.

باليوباثولوجيا (علم الأمراض القديمة) أظهرت دراسة بقايا الإنسان الماهر المؤرخة على نحو 1,8 مليون سنة خلت على أن هذا الإنسان كان يعاني من بعض الأمراض العظمية كالفصال والتهاب المفاصل الرثياني.

الثقافة

المجتمع

Typically, H. ergaster / H. erectus is considered to have been the first human to have lived in a monogamous society, and all preceding hominins were polygynous. However, it is highly difficult to speculate with any confidence the group dynamics of early hominins. The degree of sexual dimorphism and the size disparity between males and females is often used to correlate between polygyny with high disparity and monogamy with low disparity based on general trends (though not without exceptions) seen in modern primates. Rates of sexual dimorphism are difficult to determine as early hominin anatomy is poorly known, and are largely based on few specimens. In some cases, sex is arbitrarily determined in large part based on perceived size and apparent robustness in the absence of more reliable elements in sex identification (namely the pelvis). Mating systems are also based on dental anatomy, but early hominins possess a mosaic anatomy of different traits not seen together in modern primates; the enlarged cheek teeth would suggest marked size-related dimorphism and thus intense male–male conflict over mates and a polygynous society, but the small canines should indicate the opposite. Other selective pressures, including diet, can also dramatically impact dental anatomy.[26] The spatial distribution of tools and processed animal bones at the FLK Zinj and PTK sites in Olduvai Gorge indicate the inhabitants used this area as a communal butchering and eating grounds, as opposed to the nuclear family system of modern hunter gatherers where the group is subdivided into smaller units each with their own butchering and eating grounds.[27]

The behaviour of early Homo, including H. habilis, is sometimes modelled on that of savanna chimps and baboons. These communities consist of several males (as opposed to a harem society) in order to defend the group on the dangerous and exposed habitat, sometimes engaging in a group display of throwing sticks and stones against enemies and predators.[28] The left foot OH 8 seems to have been bitten off by a crocodile,[29] possibly Crocodylus anthropophagus,[30] and the leg OH 35, which either belongs to P. boisei or H. habilis, shows evidence of leopard predation.[29] H. habilis and contemporary hominins were likely predated upon by other large carnivores of the time, such as (in Olduvai Gorge) the hunting hyena Chasmaporthetes nitidula, and the saber-toothed cats Dinofelis and Megantereon.[31] In 1993, American palaeoanthropologist Leslie C. Aiello and British evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar estimated that H. habilis group size ranged from 70–85 members—on the upper end of chimp and baboon group size—based on trends seen in neocortex size and group size in modern non-human primates.[32]

H. habilis coexisted with H. rudolfensis, H. ergaster / H. erectus, and P. boisei. It is unclear how all of these species interacted.[3][33][34] To explain why P. boisei was associated with Olduwan tools despite not being the knapper (the one who made the tools), Leakey and colleagues, when describing H. habilis, suggested that one possibility was P. boisei was killed by H. habilis,[4] perhaps as food.[5] However, when describing P. boisei 5 years earlier, Louis Leakey said, "There is no reason whatever, in this case, to believe that the skull represents the victim of a cannibalistic feast by some hypothetical more advanced type of man."[35]

الغذاء

It is typically thought that the diets of H. habilis and other early Homo had a greater proportion of meat than Australopithecus, and that this led to brain growth. The main hypotheses regarding this are: meat is energy- and nutrient-rich and put evolutionary pressure on developing enhanced cognitive skills to facilitate strategic scavenging and monopolise fresh carcasses, or meat allowed the large and calorie-expensive ape gut to decrease in size allowing this energy to be diverted to brain growth. Alternatively, it is also suggested that early Homo, in a drying climate with scarcer food options, relied primarily on underground storage organs (such as tubers) and food sharing, which facilitated social bonding among both male and female group members. However, unlike what is presumed for H. ergaster and later Homo, short-statured early Homo are generally considered to have been incapable of endurance running and hunting, and the long and Australopithecus-like forearm of H. habilis could indicate early Homo were still arboreal to a degree. Also, organised hunting and gathering is thought to have emerged in H. ergaster. Nonetheless, the proposed food-gathering models to explain large brain growth necessitate increased daily travel distance.[36] It has also been argued that H. habilis instead had long, modern humanlike legs and was fully capable of effective long distance travel, while still remaining at least partially arboreal.[16]

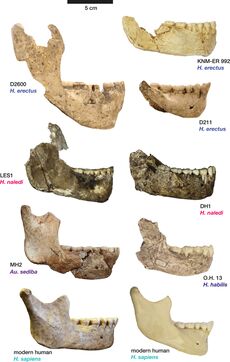

Large incisor size in H. habilis compared to Australopithecus predecessors implies this species relied on incisors more. The bodies of the mandibles of H. habilis and other early Homo are thicker than those of modern humans and all living apes, more comparable to Australopithecus. The mandibular body resists torsion from the bite force or chewing, meaning their jaws could produce unusually powerful stresses while eating. The greater molar cusp relief in H. habilis compared to Australopithecus suggests the former used tools to fracture tough foods (such as pliable plant parts or meat), otherwise the cusps would have been more worn down. Nonetheless, the jaw adaptations for processing mechanically challenging food indicates technological advancement did not greatly affect diet.[37]

It is thought H. habilis derived meat from scavenging rather than hunting (scavenger hypothesis), acting as a confrontational scavenger and stealing kills from smaller predators such as jackals or cheetahs.[38] Fruit was likely also an important dietary component, indicated by dental erosion consistent with repetitive exposure to acidity.[39] Based on dental microwear-texture analysis, H. habilis (like other early Homo) likely did not regularly consume tough foods. Microwear-texture complexity is, on average, somewhere between that of tough-food eaters and leaf eaters (folivores),[40] and points to an increasingly generalised and omnivorous diet.[41]

التكنولوجيا

H. habilis is associated with the Early Stone Age Oldowan stone tool industry. Individuals likely used these tools primarily to butcher and skin animals and crush bones, but also sometimes to saw and scrape wood and cut soft plants. Knappers appear to have carefully selected lithic cores and knew that certain rocks would break in a specific way when struck hard enough and on the right spot, and they produced several different types, including choppers, polyhedrons, and discoids. Nonetheless, specific shapes were likely not thought of in advance, and probably stem from a lack of standardisation in producing such tools as well as the types of raw materials at the knappers' disposal.[5][42] For example, spheroids are common at Olduvai which features an abundance of large and soft quartz and quartzite pieces, whereas Koobi Fora lacks spheroids and provides predominantly hard basalt lava rocks. Unlike the later Acheulean culture invented by H. ergaster / H. erectus, Oldowan technology does not require planning and foresight to manufacture, and thus does not indicate high cognition in Oldowan knappers, though it does require a degree of coordination and some knowledge of mechanics. Oldowan tools infrequently exhibit retouching and were probably discarded immediately after use most of the time.[42]

The Olduwan was first reported in 1934, but it was not until the 1960s that it become widely accepted as the earliest culture, dating to 1.8 mya, and as having been manufactured by H. habilis. Since then, more discoveries have placed the origins of material culture substantially backwards in time,[5] with the Oldowan being discovered in Ledi-Geraru and Gona in Ethiopia dating to 2.6 mya, perhaps associated with the evolution of the genus.[43][5] Australopithecines are also known to have manufactured tools, such as the 3.3 Ma Lomekwi stone tool industry,[44] and some evidence of butchering from about 3.4 mya.[45] Nonetheless, the comparatively sharp-edged Oldowan culture was a major innovation from australopithecine technology, and it would have allowed different feeding strategies and the ability to process a wider range of foods, which would have been advantageous in the changing climate of the time.[43] It is unclear if the Oldowan was independently invented or if it was the result of hominin experimentation with rocks over hundreds of thousands of years across multiple species.[5]

In 1962, a 366 cm × 427 cm × 30 cm (12 ft × 14 ft × 1 ft) circle made with volcanic rocks was discovered in Olduvai Gorge. At 61–76 cm (2–2.5 ft) intervals, rocks were piled up to 15–23 cm (6–9 in) high. Mary Leakey suggested the rock piles were used to support poles stuck into the ground, possibly to support a windbreak or a rough hut. Some modern day nomadic tribes build similar low-lying rock walls to build temporary shelters upon, bending upright branches as poles and using grasses or animal hide as a screen.[46] Dating to 1.75 mya, it is attributed to some early Homo, and is the oldest claimed evidence of architecture.[47]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

أحفوراته

KNM ER 1813

OH 7

OH 24

KNM ER 1805

إثيوپيا 2015

في مارس 2015، أُكتشفت في إثيوپيا، عظمة للفك العلوي للإنسان الماهر، تعود إلى 2.8 مليون عام، وهي أقدم من الفترة التي رجح العلماء ظهور الإنسان فيها بحوالي 400 ألف عام. ويرجح الاكتشاف أن التغير المناخي كان هو الدافع وراء الانتقال من العيش على الأشجار إلى المشي بشكل مستقيم.[48]

وحسب رئيس الفريقي البحثي، فإن هذا الاكتشاف يوضح أهم المراحل الانتقالية في تطور البشر. وهو يوضح الصلة بحفرية شبيهة بالبشر، باسم لوسي، ترجع إلى 3.2 مليون عام، اكتشفت عام 1974 في نفس المنطقة.

والحفرية المكتشفة هي للجانب الأيسر من الفك السفلي، وبها خمسة أسنان. وتعتبر أقدم حفرية تنتمي للجنس البشري.

التفسيرات

انظر أيضاً

- قائمة مواقع الأحفورات (مع دليل وصلات)

- List of human evolution fossils (with images)

الهامش

- ^ Richard Leakey describes the discovery and naming of the first H. habilis in The Making of Mankind, pp 65-66 of the Dutton 1981 hardcover edition. It was found by جوناثان ليكي at Olduvai, and was called at first "Jonny's child." Leakey says that Louis named the species for its "ability to make tools " and that habilis means "skillful". By another account (طالع في الملاحظات لويس ليكي) طلب لويس إسماً من ريموند دارت، والذي ترجمه فلپ توبياس على أنه "إنسان ماهر handyman." Later it became OH 7 described under "Famous specimens" below.

- ^ "Toothy Tree-Swinger May Be Earliest Human"

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Tobias, P. V. (2006). "Homo habilis—A Premature Discovery: Remembered by One of Its Founding Fathers, 42 Years Later". The First Humans – Origin and Early Evolution of the Genus Homo. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology. Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 7–15. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9980-9_2. ISBN 978-1-4020-9980-9.

- ^ أ ب ت Leakey, L.; Tobias, P. V.; Napier, J. R. (1964). "A New Species of the Genus Homo from Olduvai Gorge" (PDF). Nature. 202 (4927): 7–9. Bibcode:1964Natur.202....7L. doi:10.1038/202007a0. PMID 14166722. S2CID 12836722.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح de la Torre, I. (2011). "The origins of stone tool technology in Africa: a historical perspective". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 366 (1567): 1028–1037. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0350. PMC 3049100. PMID 21357225.

- ^ أ ب Wood, B.; Richmond, B. G. (2000). "Human evolution: taxonomy and paleobiology". Journal of Anatomy. 197: 39–41. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19710019.x. PMC 1468107. PMID 10999270.

- ^ أ ب Tobias, P. V. (1983). "Hominid evolution in Africa" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Anthropology. 3 (2): 163–183.

- ^ أ ب Johanson, D. C.; Masao, F.; Eck, G. G.; White, T. D.; et al. (1987). "New partial skeleton of Homo habilis from Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania". Nature. 327 (6119): 205–209. doi:10.1038/327205a0. PMID 3106831. S2CID 4321698.

- ^ Wood, B. (1985). "Early Homo in Kenya, systematic relationships". In Delson, E. (ed.). Ancestors: The hard evidence. Alan R. Liss. ISBN 978-0-8451-0249-7.

- ^ Wood, B. (1999). "Homo rudolfensis Alexeev, 1986: Fact or phantom?". Journal of Human Evolution. 36 (1): 115–118. doi:10.1006/jhev.1998.0246. PMID 9924136.

- ^ Curnoe, D. (2010). "A review of early Homo in southern Africa focusing on cranial, mandibular and dental remains, with the description of a new species (Homo gautengensis sp. nov.)". HOMO - Journal of Comparative Human Biology. 61 (3): 151–177. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2010.04.002. PMID 20466364.

- ^ Wood, B.; Collard, M. (1999). "The Human Genus". Science. 284 (5411): 65–71. doi:10.1126/science.284.5411.65. PMID 10102822.

- ^ Miller J. M. A. (2000). "Craniofacial variation in Homo habilis: an analysis of the evidence for multiple species". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 112 (1): 103–128. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(200005)112:1<103::AID-AJPA10>3.0.CO;2-6. PMID 10766947.

- ^ Tobias, P. V. (1991). "The species Homo habilis: example of a premature discovery". Annales Zoologici Fennici. 28 (3–4): 371–380. JSTOR 23735461.

- ^ Collard, Mark; Wood, Bernard (2015). "Defining the Genus Homo". Handbook of Paleoanthropology. pp. 2107–2144. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-39979-4_51. ISBN 978-3-642-39978-7.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHaeusler2004 - ^ Margvelashvili, A.; Zollikofer, C. P. E.; Lordkipanidze, D.; Peltomäki, T.; Ponce de León, M. S. (2013). "Tooth wear and dentoalveolar remodeling are key factors of morphological variation in the Dmanisi mandibles". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (in الإنجليزية). 110 (43): 17278–83. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11017278M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316052110. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3808665. PMID 24101504.

- ^ Lordkipanidze, D.; Ponce de León, M. S.; Margvelashvili, A.; Rak, Y.; Rightmire, G. P.; Vekua, A.; Zollikofer, C. P. E. (2013). "A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo". Science (in الإنجليزية). 342 (6156): 326–331. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..326L. doi:10.1126/science.1238484. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 24136960. S2CID 20435482.

- ^ Strait, D.; Grine, F.; Fleagle, J. G. (2015). "Analyzing Hominin Phylogeny: Cladistic Approach" (PDF). In Henke, W.; Tattersall, I. (eds.). Handbook of Paleoanthropology (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 2006. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-39979-4_58. ISBN 978-3-642-39979-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ Tattersall, I. (2019). "Classification and phylogeny in human evolution". Ludus Vitalis. 9 (15): 139–140.

- ^ Tattersall, I.; Schwartz, J. H. (2001). Extinct Humans. Basic Books. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-8133-3918-4.

- ^ Strait, D.; Grine, F. E.; Fleagle, J. G. (2014). "Analyzing Hominin Phylogeny: Cladistic Approach". Handbook of Paleoanthropology (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 2005–2006. ISBN 978-3-642-39979-4.

- ^ Villmoare, B.; Kimbel, W. H.; Seyoum, C.; et al. (2015). "Early Homo at 2.8 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Afar, Ethiopia". Science. 347 (6228): 1352–1355. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1343. PMID 25739410.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةSpoor2015 - ^ Zhu, Z.; Dennell, R.; Huang, W.; Wu, Y.; Qiu, S.; Yang, S.; Rao, Z.; Hou, Y.; Xie, J.; Han, J.; Ouyang, T. (2018). "Hominin occupation of the Chinese Loess Plateau since about 2.1 million years ago". Nature. 559 (7715): 608–612. Bibcode:2018Natur.559..608Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0299-4. PMID 29995848. S2CID 49670311.

- ^ Werner, J. J. (2012). "Mating Behavior in Australopithecus and Early Homo: A Review of the Diagnostic Potential of Dental Dimorphism". University of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology. 22 (1): 11–19.

- ^ Domínguez-Rodrigo, M.; Cobo-Sánchez, L. (2017). "A spatial analysis of stone tools and fossil bones at FLK Zinj 22 and PTK I (Bed I, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania) and its bearing on the social organization of early humans". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 488: 28–34. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.04.010.

- ^ Willems, Erik P.; van Schaik, Carel P. (2017). "The social organization of Homo ergaster: Inferences from anti-predator responses in extant primates". Journal of Human Evolution. 109: 17. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.05.003. PMID 28688456.

- ^ أ ب Njau, J. K.; Blumenschine, R. J. (2012). "Crocodylian and mammalian carnivore feeding traces on hominid fossils from FLK 22 and FLK NN 3, Plio-Pleistocene, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania". Journal of Human Evolution. 63 (2): 408–417. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.05.008. PMID 21937084.

- ^ Brochu, C. A.; Njau, J.; Blumenschine, R. J.; Densmore, L. D. (2010). "A New Horned Crocodile from the Plio-Pleistocene Hominid Sites at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania". PLOS ONE. 5 (2): e9333. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9333B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009333. PMC 2827537. PMID 20195356.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Lee-Thorp, J.; Thackeray, J. F.; der Merwe, N. V. (2000). "The hunters and the hunted revisited". Journal of Human Evolution. 39 (6): 565–576. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0436. PMID 11102267.

- ^ Aiello, Leslie C.; Dunbar, R. I. M. (1993). "Neocortex Size, Group Size, and the Evolution of Language". Current Anthropology. 34 (2): 188. doi:10.1086/204160. S2CID 144347664.

- ^ Leakey, M. G.; Spoor, F.; Dean, M. C.; et al. (2012). "New fossils from Koobi Fora in northern Kenya confirm taxonomic diversity in early Homo". Nature. 488 (7410): 201–204. Bibcode:2012Natur.488..201L. doi:10.1038/nature11322. PMID 22874966. S2CID 4431262.

- ^ Spoor, F.; Leakey, M. G. (2007). "Implications of new early Homo fossils from Ileret, east of Lake Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 448 (7154): 688–691. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..688S. doi:10.1038/nature05986. PMID 17687323. S2CID 35845.

- ^ Leakey, L. S. B. (1959). "A new fossil skull from Olduvai". Nature. 185 (4685): 491. doi:10.1038/184491a0. S2CID 4217460.

- ^ Pontzer, H. (2012). "Ecological Energetics in Early Homo". Current Anthropology. 56 (6): 346–358. doi:10.1086/667402.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةUngar2006 - ^ Cavallo, J. A.; Blumenschine, R. J. (1989). "Tree-stored leopard kills: expanding the hominid scavenging niche". Journal of Human Evolution. 18 (4): 393–399. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(89)90038-9.

- ^ Peuch, P.-F. (1984). "Acidic-Food Choice in Homo habilis at Olduvai". Current Anthropology. 25 (3): 349–350. doi:10.1086/203146.

- ^ Ungar, Peter (9 February 2012). "Dental Evidence for the Reconstruction of Diet in African Early Homo". Current Anthropology. 53: S318–S329. doi:10.1086/666700.

- ^ Ungar, Peter; Grine, Frederick; Teaford, Mark; Zaatari, Sireen (1 January 2006). "Dental Microwear and Diets of African Early Homo". Journal of Human Evolution. 50 (1): 78–95. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.08.007. PMID 16226788.

- ^ أ ب Toth, N. (1985). "The oldowan reassessed: A close look at early stone artifacts". Journal of Archaeological Science. 12 (2): 101–120. doi:10.1016/0305-4403(85)90056-1.

- ^ أ ب Braun, D. R.; Aldeias, V.; Archer, W.; et al. (2019). "Earliest known Oldowan artifacts at >2.58 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Ethiopia, highlight early technological diversity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (24): 11712–11717. doi:10.1073/pnas.1820177116. PMC 6575601. PMID 31160451.

- ^ Harmand, S.; Lewis, J. E.; Feibel, C. S.; et al. (2015). "3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 521 (7552): 310–315. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..310H. doi:10.1038/nature14464. PMID 25993961. S2CID 1207285.

- ^ McPherron, Shannon P.; Zeresenay Alemseged; Curtis W. Marean; Jonathan G. Wynn; Denne Reed; Denis Geraads; Rene Bobe; Hamdallah A. Bearat (2010). "Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia". Nature. 466 (7308): 857–860. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..857M. doi:10.1038/nature09248. PMID 20703305. S2CID 4356816.

- ^ Leakey, M. D. (1971). Olduvai Gorge: Volume 3, Excavations in Beds I and II, 1960-1963. Cambridge University Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780521077231.

- ^ Ingold, T. (2000). "Building, dwelling, living: how animals and people make themselves at home in the world". The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. Psychology Press. p. 184. ISBN 9780415228329.

- ^ "اكتشاف حفرية في أثيوبيا لما يعتقد أنه من "أوائل البشر"". بي بي سي. 2015-03-06. Retrieved 2015-03-06.

المصادر

- Early Humans (Roy A. Gallant)/Copyright 2000 ISBN 0-7614-0960-2

- The Making of Mankind, Richard E. Leakey, Elsevier-Dutton Publishing Company, Inc., Copyright 1981, ISBN 0-525-150552, LC Catalog Number 81-664544.

- A New Species of Genus Homo from Olduvai Gorge (PDF), L.S.B. Leakey; P.V. Tobias; J.R. Napier, Current Anthropology, Vol.6, No.4, (Oct 1965)

وصلات خارجية

| Homo habilis

]].