جماجم دمانيسي

| Homo erectus georgicus | |

|---|---|

| |

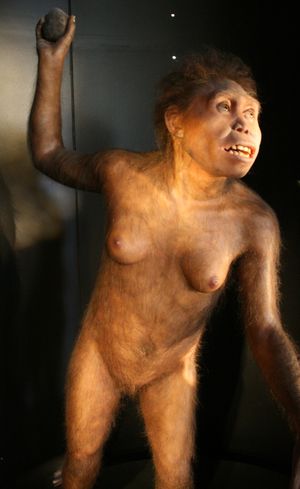

| إعادة تشكيل على D2700، قامت به إليزابث داينيس، متحف تطور الإنسان، بورگوس ، اسبانيا. | |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| أصنوفة غير معروفة (أصلحها): | الحياة |

| مملكة: | الحيوانية |

| Phylum: | حبليات |

| Class: | الثدييات |

| تحت رتبة: | جافة الأنف |

| فوق رتبة: | القرديات |

| الجنس: | هومو |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | H. e. georgicus

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Homo erectus georgicus | |

جماجم دمانيسي Dmanisi skulls هي فئة من أحفورات أشباه البشر (خمس جماجم وأربع فكوك سفلية) من الموقع الأثري بالقرب من دمانيسي، جورجيا. They were discovered in excavations at the site between 1991 and 2005.[1][2][3][4] Dated to approximately 1.85-1.75 Ma, these fossils may morphologically represent the populations of hominins that initially emigrated out of Africa.[1] Their small brain size, primitive skeletal architecture, and range of variation has been a point of debate for their taxonomic status. The fossil hominins have been described as exhibiting similarity to Homo ergaster,[1] Homo georgicus,[2] and are classified as either Homo georgicus, or as a subspecies of Homo erectus, Homo erectus georgicus.[5]

The large range of variation between the five individuals is striking due to their geographical and temporal proximity with one another. The large degree of variation present in these specimens calls into question whether or not the morphological differences between H. erectus, H. ergaster, and H. rudolfensis are due to in-species variation as well.[4] Regardless of their taxonomic position, the spatio-temporal proximity of these five individuals provide evidence for large variation in morphology within early Homo populations.

الاكتشاف

Dmanisi is a town in the Kvemo Kartli region of Georgia about 85km southwest of the capital, T’Bilisi. It is home to the 6th century cathedral Dmanisi Sioni, as well as the medieval Dmanisi Castle. Initial evidence of Plio-Pleistocene materials appeared during the 1984 excavation of medieval storage pits.[6] When the initial hominin mandible was discovered in 1991, it was incorrectly assumed to have been stored in these storage pits by medieval humans, however that claim was proven false after more thorough examination of the stratigraphy in subsequent studies.[1]

A plethora of extinct Pleistocene faunal specimens have been discovered at the site. To date, over 3000 animal fossils have been uncovered, with a majority (~70%) of the specimens being unbroken, and many being extremely well preserved (Weathering Stage 0 or 1).[2] Among these specimens include an extinct rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus etruscus etruscus), horse (Equus stenonis), deer (Cervus perrieri), and a saber toothed cat (Megantereon).[1][2]

تراتب الطبقات وتسنينها

The Dmanisi archaeological site has been extensively dated through multiple methods to approximately 1.8-1.7 Ma. The initial publication of the discovery of Skull 1 (2280) and Skull 2 (2282) provided five dating methods to support this date:[1]

- K-Ar and 40Ar/39Ar dating on the Masavera Basalt

- Paleomagnetic correlation with the Olduvai Geomagnetic Subchron

- Late-Plio-Pleistocene vertebrate fauna

- Hominin morphology similar to early African H. erectus (H. ergaster)

- Oldowan (Mode 1) stone tools

A majority of the faunal fossils are fairly well preserved due to rapid burial and relatively gentle post-mortem treatment. All fossils were buried in black/dark-brown tuffaceous sand just above the Masavera Basalt (1.85 Ma).[2]

التبويب التصنيفي

Results from a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) performed by Rightmire et al. support the position that the Dmanisi specimens represent a morphological middle ground between H. habilis and H. erectus.[5] When comparing morphological traits which are statistically supported to best represent the variation between all H. erectus (sensu lato) specimens (Mandibular fossa breadth, supraorbital torus thickness, and cranial shape), all five Dmanisi specimens are most closely associated with H. ergaster, with only Skull 5 being an outlier in cranial shape. This research showed that the seemingly large variation of craniofacial dimensions among the Dmanisi skulls is no greater than that of H. erectus, H. sapiens, and P. boisei. Although this does not conclusively indicate how the Dmanisi specimens should be classified taxinomically, it does demonstrate how the Dmanisi skulls provide evidence for the large range of morphological variation in early Homo.

The skulls discovered at Dmanisi are the smallest brained specimens to be assigned to Homo erectus and they are among the smallest brained Homo fossils in general.[2] Because the five skulls are composed of males and females, as well as younger and older individuals, they provide an excellent glance into the range of variation present in early Homo around 1.75 Mya. Some researchers have claimed that the small brained, primitive nature of the skulls precludes them from the H. erectus species, instead opting to designate them as a separate species H. georgicus.[2][6] Others argue that the unique mix of H. habilis-like traits and H. erectus-like traits demonstrate how this branch of early Homo was a single, gradually evolving lineage.[7] Rightmire et al. have remarked that attempting to establish arbitrary boundaries between H. habilis and H. erectus is difficult when the Dmanisi skulls represent a step along the gradual evolution of the lineage, stating, "The assemblage seems clearly to be Homo but cannot unequivocally be grouped with either H. habilis or H. erectus."[5]

The marked morphological variation present among these five individuals carries broader implications for the range of variation that should be expected in early Homo as a whole. Some researchers have argued that the wide range of simultaneously occurring variation in these skulls represents the range of variation that can be expected for other early Homo species.[4] In this view, H. ergaster, H. rudolfensis, and the Dmanisi skulls would be considered geographic variants of a single, broad and diverse H. erectus species. Morphological changes would occur at the population level within the species, possibly due to geographic separation. In this view, African H. ergaster is designated H. erectus ergaster and the Dmanisi specimens would be designated H. erectus ergaster georgicus, a geographic subpopulation.[5] Others have argued the contrary, stating that the evolution of early Homo was "bushy" and that the diversity we see in morphology better represents how multiple separate Homo species coexisted during the Pleistocene.[8] This perspective separates the early to mid Pleistocene Homo species into H. habilis, H. rudolfensis, H. ergaster, and H. erectus.

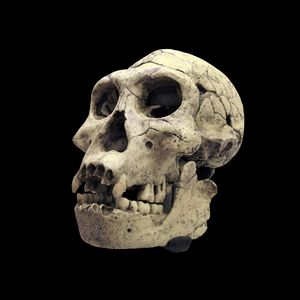

الجمجمة 1

Skull 1 (D2280) was discovered at Dmanisi in 1999, during the same field season in which Skull 2 (D2282) was discovered.[1] Skull 1, Skull 2, and the mandible for Skull 5 (D2600) were all found within the same 2m2 block on the site.

الشكل

Skull 1 (D2280) is well preserved hominin calvaria. Portions of the cranial base and occipital bone are damaged, and the zygomatic arches are missing entirely. Additionally, portions of the sphenoid and left mandibular fossa are missing. The overall shape and structure of the brain case is well preserved, allowing researchers to accurately assess the cranial capacity at 775 cc. Skull 1 has the largest brain of all of the Dmanisi specimens by an approximately ~100cc margin. Age and sex were not able to be conclusively verified due to the lack of teeth and missing facial architecture.[1]

التصنيف

Skull 1 was initially assigned to Homo ex gr. ergaster, a newly proposed Georgian regional variant of Homo ergaster.[1] This assumption was made due to the following morphological traits:

Similarities with Homo ergaster[1]

- Sharply angled cranial vault

- Moderately sized nuchal tori

- Thin, tall cranial vault

- Small calvaria breadth

- Smaller cranial capacity

Similarities with Asian Homo erectus[1]

- Well developed, angular brow ridges

- Wide eye orbits

- Occipital relief

- Single-root maxillary premolars

- Similar positions of cranial base foramina

Similarities with other hominin species[1]

- Small cranial capacity of 775cc - Most closely resembles H. habilis or H. rudolfensis specimens

The mosaic of ancestral and derived traits in Skull 1 lead to difficulty in precisely assessing whether it should be classified as H. ergaster or H. erectus sensu stricto. As such, it is sometimes considered a regional variant of H. erectus sensu lato.[1][5]

الجمجمة 2

Skull 2, a cranium (D2282) and its associated mandible (D211), was discovered in the same 1999 field season as skull 1 (D2280).[1]

الشكل

Skull 2 includes a fairly complete cranium (D2282) and a well preserved mandible (D211). The most significant damage to the cranium is its lack of facial architecture, such as the nasal bones, maxillary frontal processes, and part of the brow ridges. A majority of the cranial base is missing. The cranial vault was subject to minor lateral deformation. The cranium was still preserved well enough to make assessments about its cranial capacity, age, and sex.[1]

The cranial capacity of Skull 2 is approximately 650cc. Due to the gracile architecture of the muscle attachments, it is possible the individual was a female. Many of the mandibular teeth are still present and in great condition. The third molar was only partially erupted upon death, which indicates that the individual was likely a young adult.[1]

التصنيف

Like Skull 1, Skull 2 represents a mosaic of primitive and derived traits that may indicate it belonged to a H. ergaster population that had undergone morphological changes due to geographic separation.

Similarities with Homo ergaster:[1]

- Thin, tall cranial vault

- Narrow post-orbital region

- Occipital relief

- Narrow alveolar arch

- Moderately sized brow ridges

- Similar tooth morphology

- Similar eye orbits breadth

Differences from Homo ergaster:[1]

- Anteriorly short maxilla and mandible

- Narrow pyriform aperture

- Narrow cranial vault

- Developed mandibular symphysis

- Small premolars

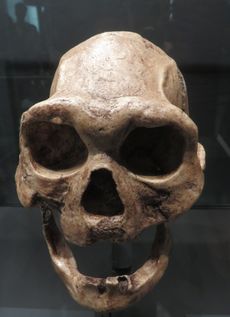

الجمجمة 3

The Skull 3 cranium (D2700) and its associated mandible (D2735) were discovered in the 2002 field season in the same strata that Skulls 1 and 2 were found in.[2]

الشكل

Skull 3 was remarkably well preserved. Other than minor cracks to the braincase, abrasion on the mastoid processes, and broken zygomatic arches, the overall structure of the cranium and mandible remained intact. Four of the maxillary teeth and eight of the mandibular teeth remained articulated in their sockets. Additionally, six disarticulated teeth were found adjacent to the skull which fit into their respective sockets well. Due to the partial eruption of the third molars, it is likely that the individual was a young teenager. The gracile structure of the facial architecture and muscle attachments indicate the individual may have been a female. Its cranial capacity is only 600 cc, smaller than Skulls 1 and 2, but still larger than the H. habilis type specimen (KNM-ER 1813).[2]

التصنيف

Skull 3 is smaller than most other H. ergaster specimens, but retains specific morphological similarities that more closely approximate it with H. ergaster than H. habilis. It is likely that due to the suite of primitive traits which Skull 3 displays, the population may have been fairly closely related to H. habilis. A cranial capacity of 600 cc is far below the lower threshold for H. erectus, falling closer to H. habilis average. However, its derived facial architecture is taken into account, researchers have stated it looks "more like a small H. erectus than H. habilis."[2]

Similarities with Homo habilis[2]

- Small cranium

- Large postglenoid process

- High distance ratio of lambda-inion to inion-opisthion

- Small facial form

- Wide nasal aperture

- Degree of postorbital constriction

Similarities with Homo ergaster[2]

- Reduction of the chin

- Low, sloping cranial walls

- Forward sloping occipital

- Curvature of the temporomandibular joint

- Angle of the petrous pyramid

- Sagittal keeling

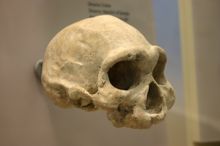

الجمجمة 4

| |

| رقم القائمة | D3444 |

|---|---|

| الاسم الشائع | Dmanisi skull 4 |

| الأنواع | Homo erectus |

| العمر | 1.8 million years |

| مكان الاكتشاف | Dmanisi, Georgia |

| تاريخ الاكتشاف | 2002-2003 |

| المكتشف | David Lordkipanidze |

Skull 4 (D3444) and its associated mandible (D3900) were discovered during the 2002-2004 field season.[3] The individual had lived for several years with only a single left canine before dying. This evidence of masticatory impairment is older than, and more extreme than previous fossils with masticatory impairment such as the La Chapelle-aux-Saints fossil and the Bau de l'Aubésier fossil. As such, its potential diet is a point of interest to researchers.[7][9] It has been suggested that the individual may have subsisted on soft matter such as soft plant tissues and bone marrow.[3][7] It is also possible that the individual was receiving assistance in mashing food before consumption, which brings an important insight into the potential social relationships between early Homo populations and the elderly.

The cranial capacity is between 625 cubic centimetres (38.1 in3) and 650 cubic centimetres (40 in3) (the imprecision is due to a missing part at the cranial base). This elderly specimen was probably a male and all but one tooth was lost before death. A lot of bone tissue around the mouth was lost due to resorption.[7]

الشكل

Skull 4 was likely an older adult male upon death. This conclusion was reached in part due to the thickness of its cranial vault and sinus development, though the complete resorption of tooth sockets years after losing teeth also could shed light on its age.[3] It is considered a male due to its projecting brow ridges, broad nasal cavity, large cheeks, and developed mastoid crests. The cranial capacity, and overall size of the skull, is fairly small for H. erectus specimens (625 cc). This provides interesting implications in the large range of sizes between same sexed individuals in this population, as Skull 5 is significantly larger.[4]

All mandibular tooth sockets had been completely resorbed upon death, except for the canines. The extensive remodeling of mandibular and maxillary architecture implies that the individual had lived mostly toothless for several years before death. It is currently unclear if the tooth loss was due to old age, pathology, or both.

التصنيف

Skull 4, like the other Dmanisi specimens, has been interpreted as a regional variant of H. erectus sensu lato.[7] The skull displays a number of morphological landmarks which identify it as H. erectus or H. ergaster, namely the projecting bar-like brow ridges, sagittal keeling, and flattened parietals. However, it also shares a number of traits unique to the Dmanisi paleodeme, such as its relatively small cranial capacity which most closely approximates values for H. habilis, its degree of midfacial projection and frontal constriction, its small third molars, and delicate tympanic plate.[7] The suite of primitive traits it shares with earlier Homo and Australopithecus species may indicated that the species represents the transition between H. habilis and H. erectus, however its similarities with Asian H. erectus provide an alternative explanation that it better represents geographic isolation of an already established H. erectus species.

Similarities with Homo erectus sensu lato[7]

- Projecting, angular brow ridges

- Elevated nasal saddle

- Flattened mastoid tip

- Sagittal keeling

- Restricted foramen lacerum

Similarities with Asian Homo erectus[7]

- Relatively flattened parietals

- Presence of occipitomastoid crests

- Presence of paramastoid crests

Similarities with other Dmanisi skulls[7]

- Small cranial capacity

- Small third molar

- Midfacial projection

- Delicate tympanic plate

- Frontal constriction

- Absence of supratubarius process

- Double sagittal keel

- Little to no chin

الجمجمة 5

Skull 5 cranium (D4500) was discovered during the 2005 field season.[4] The associated mandible (D2600) was found over a decade earlier in 1991.[10] The excellent preservation of both the cranium and mandible lead Skull 5 to be one of the most complete Pleistocene hominid skulls ever discovered.

الشكل

Skull 5 displays the smallest cranial capacity of all of the Dmanisi skulls (~545 cc). The range between the brain sizes of Skull 5 and Skull 1 (the Dmanisi skull with the largest cranial capacity) is roughly 230cc. The well preserved articulation points between the cranium and mandible also allowed researchers to finally accurately assess how the H. erectus (sensu lato) mandible oriented with the cranium.[4] The face of Skull 5 is fairly primitive, with significant prognathism, large brow ridges, and highly robust muscle attachments. Compared to the fairly gracile Skull 2 and Skull 4 (potentially a female and male respectively), Skull 5 is significantly more robust. The size of the skull indicates that the body proportions of the individual would have been largely similar to modern humans.

قحف Skull 5 is low, wide, and bell shaped, with minor sagittal keeling and a slightly sloping frontal squama. It has fairly primitive skeletal architecture, with large masticatory muscles, large zygomatic arches, and a projecting occipital protuberance. There is evidence that the individual damaged its right zygomatic arch in life, as indications of in vivo healing are present. Its highly robust architecture, namely its marked prognathism, flaring zygomatic arches, and tall and wide facial shape strongly indicate the individual was male.[4]

التصنيف

The apparent differences between Skull 5 and typical H. erectus have lead some research to classify it as a separate species, Homo georgicus,[4][7] while others insist it is evidence of the wide range of variation among the broader H. erectus population.[5]

Similarities with Homo habilis[4]

- Small cranial capacity

- Similar maxillary structure

- Similar dento-alveolar structures.

- Significant prognathism

Similarities with Homo ergaster[4]

- Similar midfacial architecture

- Wide naso-alveolar clivus

- Body size and stature (Estimated)

- Large, bar-like brow ridges

- Sloping frontal squama

الأدوات الحجرية

Over 1000 Pleistocene stone tools have been uncovered, including Oldowan (Mode 1) choppers, scrapers, and flakes.[1] These tools were manufactured from locally sourced, fine grained stone such as basalt and quartzite. Dating to about 1.7 Ma, the Dmanisi stone tool assemblage predates the earliest evidence of Acheulean bifacial handaxes, which first appear in the archaeological record around 1.6 MA. At the time of their discovery, they were some of the oldest stone tools to be found outside of Africa. Since then, 2.1 million year old Oldowan tools have been uncovered in Shangchen, China which predate the Dmanisi stone tools, providing evidence for even earlier migrations outside of Africa.[11]

Eight faunal bones with stone tool cut marks were discovered in the same stratum as Skull 4 (D3444/D3900).[3] This provides strong evidence for meat-eating at the site, which has been correlated to large home range size and more extensive logistical mobility.[12] It has been suggested that the introduction of meat to the hominin diet allowed for the support of the large energy costs involved in increased brain and body size, as well as allowing early Homo populations to survive through the winter.[12]

المراجع

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ Gabunia, Leo (2000). "Earliest Pleistocene Hominid Cranial Remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: Taxonomy, Geological Setting, and Age". Science. 288: 1019–1025. doi:10.1126/science.288.5468.1019. PMID 10807567.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س Vekua, Abesalom (2002). "A New Skull of Early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia". Science. 297: 85–89. doi:10.1126/science.1072953. PMID 12098694.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Lordkipanidze, David (2005). "The earliest toothless hominin skull". Nature. 434: 717–718. doi:10.1038/434717b. PMID 15815618.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر Lordkipanidze, David (2013). "A Complete Skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the Evolutionary Biology of Early Homo". Science. 342: 326–331. doi:10.1126/science.1238484. PMID 24136960.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Rightmire, G. Philip (2017). "Skull 5 from Dmanisi: Descriptive anatomy, comparative studies, and evolutionary significance". Journal of Human Evolution. 104: 50–79. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.01.005.

- ^ أ ب Gabunia, Leo (1995). "A Plio-Pleistocene hominid from Dmanisi, East Georgia, Caucasus". Nature. 373: 509–512. doi:10.1038/373509a0.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر David Lordkipanidze; Abesalom Vekua; Reid Ferring; G. Philip Rightmire; Christoph P.E. Zollikofer; Marcia S. Ponce de León; Jordi Agusti; Gocha Kiladze; Alexander Mouskhelishvili; Medea Nioradze; Martha Tappen (9 October 2006). "A Fourth Hominin Skull From Dmanisi, Georgia". The Anatomical Record Part A: Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology. 288: 1146–57. doi:10.1002/ar.a.20379. PMID 17031841.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Leakey, Mary (2012). "New fossils from Koobi Fora in northern Kenya confirm taxonomic diversity in early Homo". Nature. 488: 201–204. doi:10.1038/nature11322. PMID 22874966.

- ^ Margvelashvili, Ann (2013). "Tooth wear and dentoalveolar remodeling are key factors of morphological variation in the Dmanisi mandibles". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110: 17278–17283. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316052110. PMC 3808665. PMID 24101504.

- ^ Skinner, Matthew (2006). "Mandibular size and shape variation in the hominins at Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia". Journal of Human Evolution. 51: 36–49. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.01.006.

- ^ Kappelman, John (2018). "An early hominin arrival in Asia". Nature. 559: 480–481. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-05293-9.

- ^ أ ب Domínguez-Rodrigo, Manuel (2005). "Cutmarked bones from Pliocene archaeological sites at Gona, Afar, Ethiopia: implications for the function of the world's oldest stone tools". Human Evolution. 41: 109–121.