مناظرات لينكون ودوغلاس

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

شخصي

Political

16th President of the United States

العهدة الأولى

العهدة الثانية

الانتخابات الرئاسية

الاغتيال والذكرى

|

||

قالب:Events leading to American Civil War

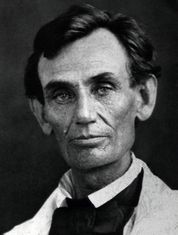

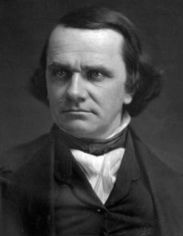

مناظرات لنكون-دگلس 1858 Lincoln–Douglas Debates كانت سلسلة من سبع مناظرات بين ابراهام لنكون، المرشح الجمهوري لمجلس الشيوخ عن إلينوي، والسناتور ستيفن دگلس، المرشح الديمقراطي. At the time, U.S. senators were elected by state legislatures; thus Lincoln and Douglas were trying for their respective parties to win control of the Illinois legislature. المناظرات كانت بمثابة عرض مسبق للقضايا التي سيواجهها لنكون لاحقاً في انتصاره في الانتخابات الرئاسية في 1860. القضية الرئيسية في كل المناظرات السبع كانت الرق.

كل منهما كان قد رشح عن حزبه لمجلس الشيوخ لنكولن عن الحزب الجمهوري، ودوجلاس يريد إعادة انتخابه عن الحزب الديمقراطي. وقد تحدى لنكولن خصمه في مناقشات تركزت على نظام الرق . قام لنكولن بمحاولة إحراج دوجلاس – الذي كان يؤمن منذ أوائل الخمسينيات بفكرة (السيادة الشعبية) في المناطق – بسؤاله فيما إذا كان السكان (في منطقة ما) يمكنهم منع وجود الرق في منطقتهم بعد قرار المحكمة العليا في قضية درد سكوت – ذلك أن رأي دوجلاس باطل ومتناقض وغير صالح . وقد رد دوجلاس بالقول بأن سكان المنطقة يمكنهم منع الرق من منطقتهم بإقرار قوانين للبوليس المحلي تمنع حماية هذا النظام في منطقتهم . كان دوجلاس قد كسب الإنتخاب من لنكولن، ولكن إجابة دوجلاس لم تعجب الديمقراطيين ، بل ساعدت على توسيع هوة الخلاف بين ديمقراطي الشمال والجنوب . وكانت المناقشة قد رفعت من شعبية لنكولن في الشمال وساعدته على النجاح في انتخابات الرئاسة عن الحزب الجمهوري عام 1861.

Never in American history had there been newspaper coverage of such intensity. Both candidates felt they were talking to the whole nation.[1] New technology was readily available: railroads, the telegraph, and Pitman shorthand, at the time called phonography. The state's largest newspapers, from Chicago, sent phonographers (stenographers) to report complete texts of each debate; thanks to the new railroads, the debates were not hard to reach from Chicago. Halfway through each debate, runners were handed the stenographers' notes. They raced for the next train to Chicago, handing them to riding stenographers who during the journey converted the shorthand back into words, producing a transcript ready for the Chicago typesetter and for the telegrapher, who sent it to the rest of the country (east of the Rockies) as soon as it arrived.[1] The next train brought the conclusion. The papers published the speeches in full, sometimes within hours of their delivery. Some newspapers helped their own candidate with minor corrections, reports on the audience's positive reaction, or tendentious headlines ("New and Powerful Argument by Mr. Lincoln—Douglas Tells the Same Old Story").[2] The newswire of the Associated Press sent messages simultaneously to multiple points, so newspapers all across the country (east of the Rocky Mountains) printed them, and the debates quickly became national events. They were republished as pamphlets.[3][4]

The debates took place between August and October 1858. Newspapers reported 12,000 in attendance at Ottawa,[5] 16,000 to 18,000 in Galesburg,[2] 15,000 in Freeport,[6] 12,000 in Quincy, and at the last one, in Alton, 5,000 to 10,000.[4] The debates near Illinois's borders (Freeport, Quincy, and Alton) drew large numbers of people from neighboring states.[7][استشهاد ناقص][8] A number travelled within Illinois to follow the debates.[5]

Douglas was re-elected by the Illinois General Assembly, 54–46.[9] But the publicity made Lincoln a national figure and laid the groundwork for his 1860 presidential campaign.

As part of that endeavor, Lincoln edited the texts of all the debates and had them published in a book.[10] It sold well and helped him receive the Republican Party's nomination for president at the 1860 Republican National Convention in Chicago.

Background

Douglas had first been elected to the United States Senate in 1846, and he was seeking re-election for a third term in 1858. The issue of slavery was raised several times during his tenure in the Senate, particularly with respect to the Compromise of 1850. As chairman of the committee on U.S. territories, he argued for an approach to slavery called popular sovereignty: electorates in the territories would vote whether to adopt or reject slavery. Decisions previously had been made at the federal level concerning slavery in the territories. Douglas was successful with passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act in 1854.[بحاجة لمصدر] The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History's Mr. Lincoln and Friends Society notes that prominent Bloomington, Illinois resident Jesse W. Fell, a local real estate developer who founded the Bloomington Pantagraph and who befriended Lincoln in 1834, had suggested the debates in 1854.[11]

Lincoln had also been elected to Congress in 1846, and he served a two-year term in the House of Representatives. During his time in the House, he disagreed with Douglas and supported the Wilmot Proviso, which sought to ban slavery in any new territory. He returned to politics in the 1850s to oppose the Kansas–Nebraska Act and to help develop the new Republican Party.[12]

Before the debates, Lincoln charged that Douglas was encouraging fears of amalgamation of the races, with enough success to drive thousands of people away from the Republican Party.[13] Douglas replied that Lincoln was an abolitionist for saying that the American Declaration of Independence applied to blacks as well as whites.[14]

Lincoln argued in his House Divided Speech that Douglas was part of a conspiracy to nationalize slavery. Lincoln said that ending the Missouri Compromise ban on slavery in Kansas and Nebraska was the first step in this nationalizing and that the Dred Scott decision was another step in the direction of spreading slavery into Northern territories. He expressed the fear that any similar Supreme Court decision would turn Illinois into a slave state.[15]

Much has been written of Lincoln's rhetorical style but, going into the debates, Douglas's reputation was a daunting one. As James G. Blaine later wrote:

He [Douglas] was everywhere known as a debater of singular skill. His mind was fertile in resources. He was master of logic. No man perceived more quickly than he the strength or the weakness of an argument, and no one excelled him in the use of sophistry and fallacy. Where he could not elucidate a point to his own advantage, he would fatally becloud it for his opponent. In that peculiar style of debate, which, in its intensity, resembles a physical contest, he had no equal. He spoke with extraordinary readiness. There was no halting in his phrase. He used good English, terse, vigorous, pointed. He disregarded the adornments of rhetoric,—rarely used a simile. He was utterly destitute of humor, and had slight appreciation of wit. He never cited historical precedents except from the domain of American politics. Inside that field his knowledge was comprehensive, minute, critical. Beyond it his learning was limited. He was not a reader. His recreations were not in literature. In the whole range of his voluminous speaking it would be difficult to find either a line of poetry or a classical allusion. But he was by nature an orator; and by long practice a debater. He could lead a crowd almost irresistibly to his own conclusions. He could, if he wished, incite a mob to desperate deeds. He was, in short, an able, audacious, almost unconquerable opponent in public discussion.[16]

المناظرات

قالب:Lincoln-Douglas debates (map) When Lincoln made the debates into a book, in 1860, he included the following material as preliminaries:

- Speech at Springfield by Lincoln, June 16, the "Lincoln's House Divided Speech" speech (in the volume, the erroneous date June 17 is given)

- Speech at Chicago by Douglas, July 9

- Speech at Chicago by Lincoln, July 10

- Speech at Bloomington by Douglas, July 16

- Speech at Springfield by Douglas, July 17 (Lincoln was not present)

- Speech at Springfield by Lincoln, July 17 (Douglas was not present)

- Preliminary correspondence of Lincoln and Douglas, July 24–31[10]

The debates were held in seven towns in the state of Illinois:

- Ottawa on August 21

- Freeport on August 27

- Jonesboro on September 15

- Charleston on September 18

- Galesburg on October 7

- Quincy on October 13

- Alton on October 15

Slavery was the main theme of the Lincoln–Douglas debates, particularly the issue of slavery's expansion into the territories. Douglas's Kansas–Nebraska Act repealed the Missouri Compromise's ban on slavery in the territories of Kansas and Nebraska and replaced it with the doctrine of popular sovereignty, which meant that the people of a territory would vote as to whether to allow slavery. During the debates, both Lincoln and Douglas appealed to the "Fathers" (Founding Fathers) to bolster their cases.[17][18][19]

النتائج

The October surprise of the election was the endorsement of the Democrat Douglas by former Whig John J. Crittenden. Former Whigs comprised the biggest block of swing voters, and Crittenden's endorsement of Douglas rather than Lincoln, also a former Whig, reduced Lincoln's chances of winning. [20]

التخليد

The debate locations in Illinois feature plaques and statuary of Douglas and Lincoln.[21]

There is a Lincoln–Douglas Debate Museum in Charleston.

In 1994, C-SPAN aired a series of re-enactments of the debates filmed on location.[22]

In 2008, BBC Audiobooks America recorded David Strathairn (Lincoln) and Richard Dreyfuss (Douglas) reenacting the debates.[23]

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ أ ب Bordewich, Fergus M. (September 2008). "How Lincoln Bested Douglas in Their Famous Debates". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ أ ب "Great Debate Between Douglas and Lincoln at Galesburg. Sixteen to Eighteen Thousand Persons Present. Largest Procession of the Campaign for Old Abe. New and Powerful Argument by Mr. Lincoln. Douglas Tells the Same Old Story. Verbatim Report of the Speeches". Chicago Tribune. October 9, 1858. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Lincoln, Abraham; Douglas, Stephen A. (1858). Speeches of Douglas and Lincoln : delivered at Charleston, Ill., Sept. 18th, 1858.

- ^ أ ب Lincoln, Abraham; Douglas, Stephen A. (1858). The campaign in Illinois. Last joint debate. Douglas and Lincoln at Alton, Illinois. [From the Chicago Daily Times. This edition published by partisons of Douglas]. Washington, D.C.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ أ ب "Great Debate between Lincoln and Douglas at Ottawa.—Twelve Thousand Persons Present.—The Dred Scott Champion Pulverized". New-York Tribune. August 26, 1858. p. 5 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Great Debate Between Lincoln and Douglas at Freeport. Fifteen Thousand Persons Present. The Dred Scott Champion "Trotted Out" and "Brought to his Milk." It Proves To Be Stump-tailed. Great Caving-In on the Ottawa Forgery. He Was Conscientious About It. Wily Chase's Amendment was Voted Down. Lincoln Tumbles Him All Over Stephenson County. Verbatim Report of Lincoln's Speech—Douglas' [sic] Repiy and Lincoln's Rejoinder". Chicago Tribune. August 30, 1858. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Nevins, Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1847–1852, p. 163.

- ^ "Abraham Lincoln, Speech at New Haven, Conn., March 6, 1860". Quod.lib.umich.edu. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- ^ Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Lincoln-Douglas debates". Encyclopedia Britannica, 2 Apr. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/event/Lincoln-Douglas-debates. Accessed May 24, 2021.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةFollett - ^ "Jesse W. Fell (1808-1887)".

- ^ Donald, David Herbert, Lincoln, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995, pp. 170-171.

- ^ Abraham Lincoln, Notes for Speech at Chicago, February 28, 1857.

- ^ Speech in Reply to Senator Stephen Douglas in the Lincoln-Douglas debates of the 1858 campaign for the U.S. Senate, at Chicago, Illinois (July 10, 1858).

- ^ Donald, David Herbert, Lincoln, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995, pp. 206-210.

- ^ "Blaine, James Gillespie, "Twenty Years of Congress" Vol. 1, Ch. VII". Gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Bordewich, Fergus M. "How Lincoln Bested Douglas in Their Famous Debates". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Jeffrey J. Malanson. "The Founding Fathers and the Election of 1864". Quod.lib.umich.edu. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- ^ Tracey Gutierres. "Abraham Lincoln: From Pioneer to President". Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- ^ Guelzo, Allen C. (2008). Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America. Pages 273–277, 282.

- ^ "The Lincoln-Douglas Debates". www.lookingforlincoln.com. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- ^ "C-Span, Illinois re-enact Lincoln-Douglas debates History in the Re-making". tribunedigital-baltimoresun (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- ^ "THE LINCOLN-DOUGLAS DEBATES by Abraham Lincoln Stephen Douglas Read by David Strathairn Richard Dreyfuss Michael McConnohie Allen C Guelzo | Audiobook Review".

وصلات خارجية

- Website of the Stephen A. Douglas Association

- Original Manuscripts and Primary Sources: Lincoln-Douglas Debates, First Edition 1860 Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- Illinois Civil War: Debates

- Digital History

- Bartleby Etext: Political Debates Between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas

- The Lincoln–Douglas Debates of 1858

- Mr. Lincoln and Freedom: Lincoln–Douglas Debates

- Abraham Lincoln: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Audio book of actors portraying Lincoln and Douglas debating

- Booknotes interview with Harold Holzer on The Lincoln-Douglas Debates, August 22, 1993.

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with incomplete citations from March 2021

- All articles with incomplete citations

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2020

- تاريخ إلينوي

- 1858 في الولايات المتحدة

- 1858 elections in the United States

- Speeches by Abraham Lincoln

- مناظرات

- الرق في الولايات المتحدة

- United States Senate elections

- Alton, Illinois

- Coles County, Illinois

- Freeport, Illinois

- Galesburg, Illinois

- Ottawa, Illinois

- Quincy, Illinois

- Union County, Illinois