مملكة شرق أنگليا

مملكة الأنگل الشرقيين Ēast Engla Rīce Regnum Orientalium Anglorum | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| القرن السادس–918 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| المكانة | مملكة الأنگل (القرن السادس—869) مملكة الدان (869–918) تابعة لمرسيا (654–655, 794–796, 798–825) تابعة للدان (869–918) | ||||||||

| العاصمة | Rendlesham, Dommoc | ||||||||

| اللغات الشائعة | الإنگليزية القديمة، اللاتينية | ||||||||

| الدين | الوثنية الأنگلو-ساكسونية، المسيحية الأنگلو-ساكسونية | ||||||||

| الحكومة | ملكية | ||||||||

| قائمة ملوك شرق أنگليا | |||||||||

• ?–? | Wehha of East Anglia (الأول) | ||||||||

• 902–918 | Guthrum II (الأخير) | ||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||

• تأسست | القرن السادس | ||||||||

• انحلت | 918 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

مملكة الأنگل الشرقيين (Kingdom of the East Angles ؛ الإنگليزية القديمة: Ēast Engla Rīce؛ لاتينية: Regnum Orientalium Anglorum)، تُعرف اليوم بإسم مملكة شرق أنگليا Kingdom of East Anglia، كانت مملكة مستقلة صغيرة من الأنگل تضم ما هو اليوم المقاطعات الإنگليزية نورفوك وسفوك وربما الجزء الشرقي من الفِن.[1] تشكلت المملكة في القرن السادس عقب الاستيطان الأنگلو-ساكسوني لبريطانيا. وكان يحكمها Wuffingas في القرنين السابع والثامن، ولكنها سقطت في يد مرسيا في 794، ثم هزمها الدان في 869، لتشكل جزءاً من دينلو. ثم فتحها إدوارد الأكبر وضمها إلى مملكة إنگلترة في 918.

التاريخ

The Kingdom of East Anglia was organised in the first or second quarter of the 6th century, with Wehha listed as the first King of the East Angles, followed by Wuffa.[1]

الاستيطان

الحكم الوثني

The East Angles were initially ruled by the pagan Wuffingas dynasty, apparently named after an early king Wuffa, although his name may be a back-creation from the name of the dynasty, which means "descendants of the wolf".[2] An indispensable source on the early history of the kingdom and its rulers is Bede's Ecclesiastical History,[note 1] but he provided little on the chronology of the East Anglian kings or the length of their reigns.[kease 1] Nothing is known of the earliest kings, or how the kingdom was organised, although a possible centre of royal power is the concentration of ship-burials at Snape and Sutton Hoo in eastern Suffolk. The "North Folk" and "South Folk" may have existed before the arrival of the first East Anglian kings.[kease 2]

التنصر

Anglo-Saxon Christianity became established in the 7th century. The extent to which paganism was displaced is exemplified by a lack of any East Anglian settlemen named after the old gods.[rga 1]

هجمات الڤايكنگ واستيطانهم بآخر الأمر

في 865، تعرضت شرق أنگليا للغزو من الجيش الهمجي الكبير الدنماركي، الذي احتل المشاتي وحصل على خيلاً قبل المغادرة إلى نورثمبريا.[eek 1] The Danes returned in 869 to winter at Thetford, before being attacked by the forces of Edmund of East Anglia, who was defeated and killed at Hægelisdun (identified variously as Bradfield St Clare in 983, near to his final resting place at Bury St Edmunds, Hellesdon في نورفوك (documented as Hægelisdun c. 985) أو Hoxne في سفوك،[3] and now with Maldon in Essex).[2][rga 2][4] From then on East Anglia effectively ceased to be an independent kingdom. Having defeated the East Angles, the Danes installed puppet-kings to govern on their behalf, while they resumed their campaigns against Mercia and Wessex.[5] في 878 the last active portion of the Great Heathen Army was defeated by ألفرد الأكبر وانسحب من وسكس بعد أن أبرم سلاماً. In 880 the Vikings returned to East Anglia under Guthrum, who according to the medieval historian Pauline Stafford, "swiftly adapted to territorial kingship and its trappings, including the minting of coins."[6]

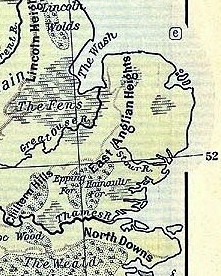

جغرافيا

The kingdom of the East Angles bordered the North Sea to the north and the east, with the River Stour historically dividing it from the East Saxons to the south. The North Sea provided a "thriving maritime link to Scandinavia and the northern reaches of Germany", according to the historian Richard Hoggett. The kingdom's western boundary varied from the rivers Ouse, Lark and Kennett to further westwards, as far as the Cam in what is now Cambridgeshire. At its greatest extent, the kingdom comprised the modern-day counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and parts of eastern Cambridgeshire.[aeac 2]

Erosion on the eastern border and deposition on the north coast altered the East Anglian coastline in Roman and Anglo-Saxon times (and continues to do so). In the latter, the sea flooded the low-lying Fens. As sea levels fell alluvium was deposited near major river estuaries and the "Great Estuary" near Burgh Castle became closed off by a large spit of land.[aeac 3]

المصادر

No East Anglian charters (and few other documents) have survived, while the medieval chronicles that refer to the East Angles are treated with great caution by scholars. So few records from the Kingdom of the East Angles have survived because of a complete destruction of the kingdom's monasteries and disappearance of the two East Anglian sees as a result of Viking raids and settlement.[kease 3] The main documentary source for the early period is Bede's 8th-century Ecclesiastical History of the English People. East Anglia is first mentioned as a distinct political unit in the Tribal Hidage, thought to have been compiled somewhere in England during the 7th century.[shoo 1]

Anglo-Saxon sources that include information about the East Angles or events relating to the kingdom:[shoo 2]

- Ecclesiastical History of the English People

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

- The Tribal Hidage, where the East Angles are assessed at 30,000 hides, evidently superior in resources to lesser kingdoms such as Sussex and Lindsey.[eek 2]

- Historia Brittonum

- Life of Foillan, written in the 7th century

Post-Norman sources (of variable historical validity):

- The 12th century Liber Eliensis

- Florence of Worcester's Chronicle, written in the 12th century

- Henry of Huntingdon's Historia Anglorum, written in the 12th century

- Roger of Wendover's Flores Historiarum, written in the 13th century

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

المراجع

- ^ أ ب One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBlackwell_154 - ^ "Hidden East Anglia – Part 5 – The Last Mystery: Where Did Edmund Die?". Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ Keith Briggs, Was Hægelisdun in Essex? A new site for the martyrdom of Edmund. Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History, Vol. XLII (2011), pp. 277–291

- ^ Forte, Angelo; Oram, Richard D.; Pedersen, Frederik (2005). Viking Empires. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- ^ Stafford, A Companion to the early Middle Ages, p. 205.

- Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (2001). Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe. London, New York: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-8264-7765-1.

- Carver, M. O. H., ed. (1992). The Age of Sutton Hoo: the Seventh Century in North-Western Europe. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-361-2.

- Fisiak, Old East Anglian

- Hoggett, Richard (2010). The Archaeology of the East Anglian Conversion. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-595-0.

- Hoops, Johannes (1986) [1911–1919]. Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde (in English and German). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co. ISBN 978-3-11-010468-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|authormask=(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-24211-0.

- Stenton, Sir Frank (1988). Anglo-Saxon England. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821716-9.

- Yorke, Barbara (2002). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16639-3.

- Warner, Peter (1996). The Origins of Suffolk. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-3817-4.

ببليوگرافيا

| Kingdom of the East Angles

]].- Hadley, Dawn (2009). "Viking Raids and Conquest". In Stafford, Pauline (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c. 500–c. 1100. Chichester: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-0628-3.

- Williams, Gareth (2001). "Mercian Coinage and Authority". In Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (eds.). Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Leicester: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-8264-7765-1.

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Wikipedia articles incorporating text from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles containing إنگليزية القديمة (ح. 450-1100)-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- مملكة شرق أنگليا

- شعوب إنگلترة الأنگلو-ساكسونية

- دول وأقاليم تأسست في القرن السادس

- تأسيسات القرن السادس في إنگلترة

- انحلالات 918

- انحلالات القرن العاشر في إنگلترة