معركة غوغميلا

| معركة گوگميلا Battle of Gaugamela | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جزء من جزء من حروب الإسكندر الأكبر | |||||||||

Alexander the Great, victorious over Darius at the Battle of Gaugamela by Jacques Courtois | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||||

|

حلفاء مقدونيا، جنوب اليونان |

الامبراطورية الأخمينية، مرتزقة يونانيون | ||||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||||

|

الإسكندر الأكبر هفستيون، كراتروس، پارمنیون، بطليموس الأول، پردیکاس، أنتيگونوس، كليتوس، نيرخوس، سلوقس |

داريوش الثالث بسوس، مزايوس، أورونتس الثاني | ||||||||

| القوى | |||||||||

|

47,000 [1][2] (See Size of Macedonian army) | 50,000-100,000[3] (تقديرات حديثة) (انظرحجم الجيش الفارسي) | ||||||||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||||||||

|

100 مشاة و1,000 سلاح الفرسان (حسب أريان)؛ 300 مشاة (حسب كورتوس روفوس); 500 مشاة (حسب ديودروس سيكولوس) |

40,000 (حسب كورتوس روفوس) 47,000 (حسب ڤلهام)[4] 90,000 (حسب ديودروس سيكولوس) 300,000+ أسير (حسب أريان)[5] | ||||||||

الموقع داخل العراق | |||||||||

معركة گوگميلا ( Battle of Gaugamela ؛ ![]() /ˌɡɔːɡəˈmiːlə/؛ باليونانية قديمة: Γαυγάμηλα, Gaugámēla, بيت الجمل)، وتسمى أيضاً معركة أربيلا (باليونانية قديمة: Ἄρβηλα, Árbēla)، وقعت في 331 ق.م. بين الإسكندر الأكبر وداريوش الثالث من فارس. المعركة، أسفرت عن النصر الحاسم للمقدونيين وأدت إلى سقوط الامبراطورية الفارسية.[6]

/ˌɡɔːɡəˈmiːlə/؛ باليونانية قديمة: Γαυγάμηλα, Gaugámēla, بيت الجمل)، وتسمى أيضاً معركة أربيلا (باليونانية قديمة: Ἄρβηλα, Árbēla)، وقعت في 331 ق.م. بين الإسكندر الأكبر وداريوش الثالث من فارس. المعركة، أسفرت عن النصر الحاسم للمقدونيين وأدت إلى سقوط الامبراطورية الفارسية.[6]

The fighting took place in Gaugamela, a village on the banks of the river Bumodus. The area today would be considered modern-day Erbil, Iraq, according to Urbano Monti's world map.[7] Alexander's army was heavily outnumbered and modern historians say that "the odds were enough to give the most experienced veteran pause".[8] Despite the overwhelming odds, Alexander's army emerged victorious due to the employment of superior tactics and the clever usage of light infantry forces. It was a decisive victory for the League of Corinth, and it led to the fall of the Achaemenid Empire and of Darius III.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

خلفية

In November 333 BC, King Darius III had lost the Battle of Issus to Alexander the Great, which resulted in the subsequent capture of his wife, his mother and his two daughters, Stateira II and Drypetis. Alexander's victory at Issus had also given him complete control of southern Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). After the battle, King Darius retreated to Babylon where he regrouped with his remaining army that was there, on-site from a previous battle.

Alexander fought at the Siege of Tyre (332 BC), which lasted from January to July, and the victory resulted in his control of the Levant. Alexander then again fought at the Siege of Gaza, which resulted in Persian troop counts becoming very low. Due to this, the Persian satrap of Egypt, Mazaeus, peacefully surrendered to Alexander.[9][مطلوب توضيح]

المفاوضات بين داريوس والإسكندر

Darius tried to dissuade Alexander from further attacks on his empire by diplomacy. Ancient historians provide different accounts of his negotiations with Alexander, which can be separated into three negotiation attempts.[10]

Historians Justin, Arrian and Curtius Rufus, writing in the 1st and 2nd centuries, say that Darius had sent a letter to Alexander after the Battle of Issus. The letter demanded that Alexander withdraw from Asia as well as release all of his prisoners. According to Curtius and Justin, Darius offered a ransom for his prisoners, although Arrian does not mention a ransom. Curtius describes the tone of the letter as offensive,[11] and Alexander refused his demands.

A second negotiation attempt took place after the capture of Tyre. Darius offered Alexander marriage with his daughter Stateira II, as well as all the territory west of the Halys River. Justin is less specific, and does not mention a specific daughter, and only speaks of a portion of Darius' kingdom.[12] Diodorus Siculus (1st century Greek historian) likewise mentions the offer of all territory west of the Halys River, a treaty of friendship and a large ransom for Darius' captives. Diodorus is the only ancient historian who mentions the fact that Alexander concealed this letter and presented his friends with a forged one that was favorable to his own interests. Again, Alexander refused Darius' offers.[13]

King Darius started to prepare for another battle with Alexander after the failure of the second negotiation attempt. Nevertheless, Darius made a third and final effort to negotiate with Alexander the Great after Alexander had departed from Egypt. Darius' third offer was much more generous. He praised Alexander for the treatment of his mother Sisygambis, offered him all territory west of the Euphrates, co-rulership of the Achaemenid Empire, the hand of one of his daughters and 30,000 talents of silver. In the account of Diodorus, Alexander explicitly deliberated this offer with his friends. Parmenion was the only one who spoke up, saying, "If I were Alexander, I should accept what was offered and make a treaty." Alexander reportedly replied, "So should I, if I were Parmenion." Alexander, in the end, refused the offer of Darius, and insisted that there could be only one king of Asia. He called on Darius to surrender to him or to meet him in battle in order to decide who would be the sole king of Asia.[14]

The descriptions given by other historians of the third negotiation attempt are similar to the account of Diodorus, but differ in details. Diodorus, Curtius and Arrian write that an embassy[15] was sent instead of a letter, which is also claimed by Justin and Plutarch (1st century).[16] Plutarch and Arrian mention the ransom offered for the prisoners was 10,000 talents, but Diodorus, Curtius and Justin had given the figure of 30,000. Arrian writes that Darius' third attempt took place during the Siege of Tyre, but the other historians place the second negotiation attempt at that time.[17] In spite of everything, with the failure of his negotiation attempts, Darius had now decided to prepare for another battle with Alexander.

تمهيد

After settling affairs in Egypt, Alexander returned to Tyre during the spring of 331 BC.[18] He reached Thapsacus in July or August.[19] Arrian relates that Darius had ordered Mazaeus to guard the crossing of the Euphrates near Thapsacus with a force of 3,000 cavalry. He fled when Alexander's army approached to cross the river.[20]

زحف الإسكندر في بلاد الرافدين

After crossing the Euphrates, Alexander followed a northern route instead of a direct southeastern route to Babylon. While doing so he had the Euphrates and the mountains of Armenia on his left. The northern route made it easier to forage for supplies and his troops would not suffer the extreme heat of the direct route. Captured Persian scouts reported to the Macedonians that Darius had encamped past the Tigris River and wanted to prevent Alexander from crossing. Alexander found the Tigris undefended and succeeded in crossing it with great difficulty.[20]

In contrast, Diodorus mentions that Mazaeus was only supposed to prevent Alexander from crossing the Tigris. He would not have bothered to defend it because he considered it impassable due to the strong current and depth of the river. Furthermore, Diodorus and Curtius Rufus mention that Mazaeus employed scorched-earth tactics in the countryside through which Alexander's army had to pass.[21]

After the Macedonian army had crossed the Tigris a lunar eclipse occurred.[20] Following the calculations, the date must have been October 1 in 331 BC.[22] Alexander then marched southward along the eastern bank of the Tigris. On the fourth day after the crossing of the Tigris his scouts reported that Persian cavalry had been spotted, numbering no more than 1000 men. When Alexander attacked them with his cavalry force ahead of the rest of his army, the Persian cavalry fled. Most of them escaped, but some were killed or taken prisoner. The prisoners told the Macedonians that Darius was not far away, with his encampment near Gaugamela.[23]

تحليل استراتيجي

Several researchers have criticized the Persians for their failure to harass Alexander's army and disrupt its long supply lines when it advanced through Mesopotamia.[24] Classical scholar Peter Green thinks that Alexander's choice for the northern route caught the Persians off guard. Darius would have expected him to take the faster southern route directly to Babylon, just as Cyrus the Younger had done in 401 BC before his defeat in the Battle of Cunaxa. The use of the scorched-earth tactic and scythed chariots by Darius suggests that he wanted to repeat that battle. Alexander would have been unable to adequately supply his army if he had taken the southern route, even if the scorched-earth tactic had failed. The Macedonian army, underfed and exhausted from the heat, would then be defeated at the plain of Cunaxa by Darius. When Alexander took the northern route, Mazaeus must have returned to Babylon to bring the news. Darius most likely decided to prevent Alexander from crossing the Tigris. This plan failed because Alexander probably took a river crossing that was closer to Thapsacus than Babylon. He would have improvised and chosen Gaugamela as his most favourable site for a battle.[25] Historian Jona Lendering argues the opposite and commends Mazaeus and Darius for their strategy. Darius would have deliberately allowed Alexander to cross the rivers unopposed in order to guide him to the battlefield of his own choice.[26]

الموقع

Darius chose a flat, open plain where he could deploy his larger forces, not wanting to be caught in a narrow battlefield as he had been at Issus two years earlier, where he could not deploy his huge army properly. Darius had his soldiers flatten the terrain before the battle, to give his 200 war chariots the best conditions. However, this did not matter. On the ground were a few hills and no bodies of water that Alexander could use for protection, and in the autumn the weather was dry and mild.[27] The most commonly accepted opinion about the location is (36°22′N 43°15′E / 36.36°N 43.25°E), east of Mosul in modern-day northern Iraq – suggested by archeologist Sir Aurel Stein in 1938.[28]

حجم الجيش الفارسي

تقديرات معاصرة

| الوحدات | أقل التقديرات | أعلى التقديرات[مطلوب توضيح] |

|---|---|---|

| Peltasts | 10,000[29] | 30,000[30] |

| سلاح الفرسان | 12,000[29] | 40,000[4] |

| الخالدون الفرس | 10,000[31] | 10,000 |

| سلاح الفرسان الباكتري | 1,000[5] | 2,000 |

| الرماة | 1,500 | 1,500 |

| Scythed chariots | 200 | 200 |

| فيلة الحرب | 15 | 15 |

| الاجمالي | 52,930[29] | 87,000[2] |

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

حجم الجيش المقدوني

التقديرات الحديثة

| الوحدات | العديد |

|---|---|

| مشاة ثقيلة | 31,000[1] |

| Peltasts | 9,000[1] |

| سلاح الفرسان | 7,000 |

| Total | 47,000[1] |

المعركة

عاد الإسكندر بجيشه إلى آسيا والتقى عند گاوگميلا قرب أربيل بجيش دارا المؤلف من خليط من الأمم، وارتاع لكثرة عدده، وكان يعرف أن هزيمة واحدة كفيلة بأن تذهب بجميع ما سبقها من انتصارات. لكن جنوده هدّأوا روعه وقالوا له: "طب نفساً أيها السيد المعظم، ولا ترهبك كثرة عدد الأعداء، لأنهم لن يستطيعوا الوقوف أمام رائحة الماعز التي تصحب جيوشنا". وقضى الليلة يستكشف الأرض التي ستدور فيها المعركة، ويقرب القرابين للآلهة. وكان نصره مؤزراً حاسماً، فلم تستطع جيوش دارا المختلة النظام أن تصمد أمام فيالق الإسكندر المتراصة، ولم تعرف كيف تدافع عن نفسها أمام هجمات الفرسان المقدونيين السريعة المتكررة، فتبدد شملها وولت الأدبار، ولم يكن دارا آخر الفارين. وقتله قواده جزاءً له على جبنه، في الوقت الذي كان الإسكندر يتقبل فيه خضوع بابل، ونصيباً من ثروتها، ويوزع بعضها على جنده، ويأسر قلوب أهل المدينة بتعظيم آلهتها وإصدار أوامر بإعادة أضرحتها المقدسة.[32]

Initial dispositions

The battle began with the Persians already present at the battlefield. Darius had recruited the finest cavalry from his Eastern satrapies and from allied Scythian tribes[مطلوب توضيح] and deployed scythed chariots, for which he had ordered bushes and vegetation removed from the battlefield to maximize their effectiveness. He also had 15 Indian elephants supported by Indian chariots.[33] However, the absence of any mention of those elephants during the battle and their later capture in the Persian camp indicate they were withdrawn. The reason might have been fatigue.[34]

Darius placed himself in the center with his best infantry, as was the tradition among Persian kings. He was surrounded by, on his right, the Carian cavalry, Greek mercenaries and Persian horse guards. In the right-center he placed Persian foot guards (Apple Bearers/Immortals to the Greeks), the Indian cavalry and his Mardian archers.

On both flanks were the cavalry. Bessus commanded the left flank with the Bactrians, Dahae cavalry, Arachosian cavalry, Persian cavalry, Susian cavalry, Cadusian cavalry and Scythians. Chariots were placed in front with a small group of Bactrians. Mazaeus commanded the right flank with the Syrian, Median, Mesopotamian, Parthian, Sacian, Tapurian, Hyrcanian, Caucasian Albanian, Sacesinian, Cappadocian and Armenian cavalry. The Cappadocians and Armenians were stationed in front of the other cavalry units and led the attack. The Albanian cavalry were sent around to flank the Greek left. According to Curtius, the archers were all Amardi.[35]

The Macedonians were divided into two, with the right side under the direct command of Alexander and the left of Parmenion.[36] Alexander fought with his Companion cavalry. With it was the Paionian and Greek light cavalry. The mercenary cavalry was divided into two groups, veterans on the flank of the right and the rest in front of the Agrians and Greek archers, who were stationed next to the phalanx. Parmenion was stationed on the left with the Thessalians, Greek mercenaries and Thracian cavalry. There they were to conduct a holding action while Alexander launched the decisive blow from the right.

On the right-center were Cretan mercenaries. Behind them were Thessalian cavalry under Phillip, and Achaean mercenaries. To their right was another part of the allied Greek cavalry. From there came the phalanx, in a double line. Outnumbered over 5:1 in cavalry, with their line surpassed by over a mile, it seemed inevitable that the Greeks would be flanked by the Persians. The second line was given orders to deal with any flanking units should the situation arise. This second line consisted mostly of mercenaries.

Beginning of the battle

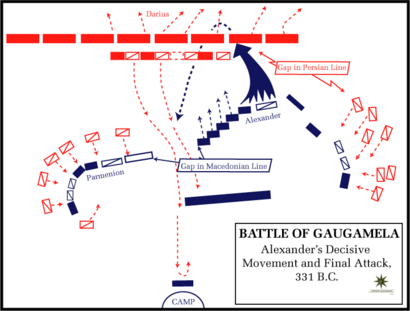

Alexander began by ordering his infantry to march in phalanx formation towards the center of the enemy line. The Macedonians advanced with the wings echeloned back at 45 degrees to lure the Persian cavalry to attack. While the phalanxes battled the Persian infantry, Darius sent a large part of his cavalry and some of his regular infantry to attack Parmenion's forces on the left.

During the battle Alexander employed an unusual strategy which has been duplicated only a few times. While the infantry battled the Persian troops in the centre, Alexander began to ride all the way to the edge of the right flank, accompanied by his Companion Cavalry. His plan was to draw as much of the Persian cavalry as possible to the flanks, to create a gap within the enemy line where a decisive blow could then be struck at Darius in the centre. This required almost perfect timing and maneuvering and Alexander himself to act first. He would force Darius to attack (as they would soon move off the prepared ground), though Darius did not want to be the first to attack after seeing what happened at Issus against a similar formation. In the end, Darius' hand was forced, and he attacked.

The cavalry battle in the Hellenic right wing

The Scythian cavalry from the Persian left wing opened the battle by attempting to flank Alexander's extreme right. What followed was a long and fierce cavalry battle between the Persian left and the Macedonian right, in which the latter, being greatly outnumbered, was often hard-pressed. However, by careful use of reserves and disciplined charges, the Greek troops were able to contain their Persian counterparts, which would be vital for the success of Alexander's decisive attack.

As told by Arrian:

Then the Scythian cavalry rode along the line, and came into conflict with the front men of Alexander's array, but he nevertheless still continued to march towards the right, and almost entirely got beyond the ground which had been cleared and levelled by the Persians. Then Darius, fearing that his chariots would become useless, if the Macedonians advanced into the uneven ground, ordered the front ranks of his left wing to ride round the right wing of the Macedonians, where Alexander was commanding, to prevent him from marching his wing any further. This being done, Alexander ordered the cavalry of the Grecian mercenaries under the command of Menidas to attack them. But the Scythian cavalry and the Bactrians, who had been drawn up with them, sallied forth against them and being much more numerous they put the small body of Greeks to rout. Alexander then ordered Aristo at the head of the Paeonians and Grecian auxiliaries to attack the Scythians, and the barbarians gave way. But the rest of the Bactrians, drawing near to the Paeonians and Grecian auxiliaries, caused their own comrades who were already in flight to turn and renew the battle; and thus they brought about a general cavalry engagement, in which more of Alexander's men fell, not only being overwhelmed by the multitude of the barbarians, but also because the Scythians themselves and their horses were much more completely protected with armour for guarding their bodies. Notwithstanding this, the Macedonians sustained their assaults, and assailing them violently squadron by squadron, they succeeded in pushing them out of rank.[37]

The tide finally turned in the Greek favor after the attack of Aretes' Prodromoi, likely their last reserve in this sector of the battlefield. By then, however, the battle had been decided in the center by Alexander himself.

The Persians also who were riding round the wing were seized with alarm when Aretes made a vigorous attack upon them. In this quarter indeed the Persians took to speedy flight; and the Macedonians followed up the fugitives and slaughtered them.[38]

Attack of the Persian scythed chariots

Darius now launched his chariots at those troops under Alexander's personal command; many of the chariots were intercepted by the Agrianians and other javelin-throwers posted in front of the Companion cavalry. Those chariots who made it through the barrage of javelins charged the Macedonian lines, which responded by opening up their ranks, creating alleys through which the chariots passed harmlessly. The Hypaspists and the armed grooms of the cavalry then attacked and eliminated these survivors.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

هجوم الإسكندر الحاسم

As the Persians advanced farther and farther to the Greek flanks in their attack, Alexander slowly filtered in his rear guard. He disengaged his Companions and prepared for the decisive attack. Behind them were the guard's brigade along with any phalanx battalions he could withdraw from the battle. He formed his units into a giant wedge, with him leading the charge. The Persian infantry at the center was still fighting the phalanxes, hindering any attempts to counter Alexander's charge. This large wedge then smashed into the weakened Persian center, taking out Darius' royal guard and the Greek mercenaries. Darius was in danger of being cut off, and the widely held modern view is that he now broke and ran, with the rest of his army following him. This is based on Arrian's account:

For a short time there ensued a hand-to-hand fight; but when the Macedonian cavalry, commanded by Alexander himself, pressed on vigorously, thrusting themselves against the Persians and striking their faces with their spears, and when the Macedonian phalanx in dense array and bristling with long pikes had also made an attack upon them, all things together appeared full of terror to Darius, who had already long been in a state of fear, so that he was the first to turn and flee.[38]

الميسرة

Alexander could have pursued Darius at this point. However, he received desperate messages from Parmenion (an event that would later be used by Callisthenes and others to discredit Parmenion) on the left. Parmenion's wing was apparently encircled by the cavalry of the Persian right wing; being attacked from all sides, it was in a state of confusion. Alexander was faced with the choice of pursuing Darius and having the chance of killing him, ending the war in one stroke but at the risk of losing his army, or going back to the left flank to aid Parmenion and preserve his forces, thus letting Darius escape to the surrounding mountains. He decided to help Parmenion, and followed Darius later.[39][مطلوب مصدر أفضل]

While holding on the left, a gap had opened up between the left and center of the Macedonian phalanx, due to Simmias' brigade of pezhetairoi being unable to follow Alexander in his decisive attack, as they were being hard-pressed. The Persian and Indian cavalry in the center with Darius broke through. Instead of taking the phalanx or Parmenion in the rear, however, they continued towards the camp to loot. They also tried to rescue the Queen Mother, Sisygambis, but she refused to go with them. These raiders were in turn attacked and dispersed by the rear reserve phalanx as they were looting.

What happened next was described by Arrian as the fiercest engagement of the battle, as Alexander and his companions encountered the cavalry of the Persian right, composed of Indians, Parthians and "the bravest and most numerous division of the Persians", desperately trying to get through to escape. Sixty Companions were killed in the engagement, and Hephaestion, Coenus and Menidas were all injured. Alexander prevailed, however, and Mazaeus also began to pull his forces back as Bessus had. However, unlike on the left with Bessus, the Persians soon fell into disorder as the Thessalians and other cavalry units charged forward at their fleeing enemy.

الأعقاب

After the battle, Parmenion rounded up the Persian baggage train while Alexander and his bodyguard pursued Darius. As at Issus, substantial loot was gained, with 4,000 talents captured, the King's personal chariot and bow and the war elephants. It was a disastrous defeat for the Persians and one of Alexander's finest victories.

Darius managed to escape by horseback [40] with a small corps of his forces remaining intact. The Bactrian cavalry and Bessus caught up with him, as did some of the survivors of the Royal Guard and 2,000 Greek mercenaries. At this point the Persian Empire was divided into two halves—East and West. On his escape, Darius gave a speech to what remained of his army. He planned to head further east and raise another army to face Alexander, assuming that the Greeks would head towards Babylon. At the same time he dispatched letters to his eastern satraps asking them to remain loyal.

The satraps, however, had other intentions. Bessus murdered Darius before fleeing eastwards. When Alexander discovered Darius murdered, he was saddened to see an enemy he respected killed in such a fashion, and gave Darius a full burial ceremony at Persepolis, the former ceremonial capital of the Persian Empire, before angrily pursuing Bessus, capturing and executing him the following year. The majority of the remaining satraps gave their loyalty to Alexander and were allowed to keep their positions. The Achaemenid Persian Empire is traditionally considered to have ended with the death of Darius.

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت ث Moerbeek (1997) estimates 31,000 phalangites and 9,000 light infantry.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةestimate - ^ Alexander Defeats the Persians, 331 BC, History.com website

- ^ أ ب Welman

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةAnabasis - ^ Lendering, Jona (August 10, 2020). "Gaugamela (331 BCE)". Livius – via Livius.org.

- ^ "Composite: Tavola 1-60. (Map of the World) (Re-projected in Plate Carree or Geographic, Marinus of Tyre, Ptolemy) - David Rumsey Historical Map Collection". www.davidrumsey.com. Retrieved 2022-02-19.

- ^ Niderost, Eric (Spring 2021). "Alexander's Triumph at Gaugamela". Military Heritage. p. 9 – via Warfare History Network.

- ^ Arrian 1893, 3.1.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus 1963, footnote 79.

- ^ Justin 1853, 11.12.1–2; Arrian 1893, 2.14; Quintus Curtius Rufus 1880, 4.1.7–14.

- ^ Justin 1853, 11.12.1–2; Quintus Curtius Rufus 1880, 4.5.1–8.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus 1963, 17.39.1–2.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus 1963, 17.54.1–6.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus 1963, 17.54.1–6; Quintus Curtius Rufus 1880, 4.11; Arrian 1893, 2.25.

- ^ Justin 1853, 11.12; Plutarch 1919, 4.29.7–9.

- ^ Arrian 1893, 2.25.

- ^ Arrian 1893, 3.6.

- ^ Arrian 1893, 3.7; Diodorus Siculus 1963, footnote 62.

- ^ أ ب ت Arrian 1893, 3.7.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus 1963, 17.55; Quintus Curtius Rufus 1880, 4.9.14.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus 1963, footnote 77.

- ^ Arrian 1893, 3.7–8.

- ^ Ward 2014, p. 24; Cummings 2004, p. 216.

- ^ Green 2013, p. 282–285.

- ^ Lendering 2004.

- ^ Hanson 2007, p. 69–72.

- ^ Stein, Auriel; Gregory, Shelagh; Kennedy, David Leslie (1985). Limes Report: His Aerial & Ground Reconnaissances in Iraq & Transjordan in 1938-39. Oxford BAR, International series. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-86054-349-7.

- ^ أ ب ت Hans Delbrück

- ^ Moerbeek (1997).

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةCurtius - ^ ديورانت, ول; ديورانت, أرييل. قصة الحضارة. ترجمة بقيادة زكي نجيب محمود.

- ^ Hanson 2007, p. 70–71.

- ^ John M. Kistler (2007). War Elephants. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6004-7.

- ^ Quintus Curtius Rufus 1880, 3.2.7: The Hyrcani had mustered 6,000 as excellent horsemen as those nations could furnish, as well as 1,000 Tapurian cavalry. The Derbices had armed 40,000 foot-soldiers ; most of these carried spears tipped with bronze or iron, but some had hardened the wooden shaft by fire.

- ^ Hanson 2007, p. 61.

- ^ Arrian 1893, 3.13.

- ^ أ ب Arrian 1893, 3.14.

- ^ Arrian 1893, 3.15.

- ^ Dave Roos (9 September 2019). "How Alexander the Great Conquered the Persian Empire". History.

وصلات خارجية

- Battle of Gaugamela animated battle map by Jonathan Webb

- Livius.org tells the story of Alexander and quotes original sources. Favors a reconstruction of the battle which heavily privileges the Babylonian astronomical diaries.

- Video : Animated reconstruction of Battle of Gaugamela History Channel

- Livius.org provides a new scholarly edition of the Babylonian Astronomical Diary concerning the battle of Gaugamela and Alexander's entry into Babylon by R.J. van der Spek.

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from May 2021

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from July 2010

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from July 2019

- كل المقالات بدون مراجع موثوقة

- كل المقالات بدون مراجع موثوقة from May 2020

- معارك الإسكندر الأكبر

- معارك الأخمينيين

- 331 ق.م.

- التاريخ العسكري للعراق

- أربيل