محطم الأيقونات

National Portrait Gallery, London

محطم الأيقونات تعبير عند النصارى يعني الشخص الذي يهاجم المعتقدات القديمة الراسخة. وهذا التعبير جاء من كلمتين يونانيتين "أيكون" ومعناها الصورة و"كلاستس" ومعناها المحطم. وفي البدايات الأولى للكنيسة، كان الأشخاص الذين يعارضون فكرة تقديم الصور يسمون محطمي الأيقونات . وقد أدى نزاع طويل إلى تقسيم الكنيسة خاصة في الشرق ، بسبب وجود صور المسيح والقديسين في الكنائس. وفي عام 726م ، أصدر الإمبراطور ليو الثالث قرارا بتغطية أو تحطيم كل الصور والرسومات الموجودة في الكنائس. وأدى هذا القرار إلى تقسيم الكنيسة إلى مجموعتين متعارضتين. فمحطمو الأيقونات كانوا يفضلون إزالة الصور، بينما كان كثير من الكهنة والناس يحبذون بقاءها.

وبعد انعقاد المجمع المسكوني الثاني للكنيسة في عام 787م ، سمحت الإمبراطورة إيرين، إمبراطورة بيزنطة، بتداول الصور وتقديسها، طالما أن هذه القداسة لا تصل إلى قداسة الرب. وفي عام 843م ، توصلت الكنيسة الشرقية إلى تسوية وافقت بمقتضاها على وجود بعض الصور والتماثيل. وفي الكنائس الرومانية الكاثوليكية تقدس الصور على أنها رموز للأشخاص الذين تمثلهم.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التحطيم الإسلامي للصور

مصر

المقريزي, writing in the 15th century, attributes the missing nose on the Great Sphinx of Giza to iconoclasm by محمد صائم الدهر، a Sufi Muslim in the mid-1300s. He was reportedly outraged by local Muslims making offerings to the Great Sphinx in the hope of controlling the flood cycle, and he was later executed for vandalism. However, whether this was actually the cause of the missing nose has been debated by historians.[4] Mark Lehner, having performed an archaeological study, concluded that it was broken with instruments at an earlier unknown time between the 3rd and 10th centuries.[5]

تحطيم الأيقونات في الهند

أثناء الفتح الإسلامي للسند

Records from the campaign recorded in the Chach Nama record the destruction of temples during the early 8th century when the Umayyad governor of Damascus, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf,[6] mobilized an expedition of 6000 cavalry under Muhammad bin Qasim in 712.

Historian Upendra Thakur records the persecution of Hindus and Buddhists:

Muhammad triumphantly marched into the country, conquering Debal, Sehwan, Nerun, Brahmanadabad, Alor and Multan one after the other in quick succession, and in less than a year and a half, the far-flung Hindu kingdom was crushed ... There was a fearful outbreak of religious bigotry in several places and temples were wantonly desecrated. At Debal, the Nairun and Aror temples were demolished and converted into mosques.[7]

- Iconoclasm during the Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent

The Somnath Temple in Gujarat was repeatedly destroyed by Islamic armies and rebuilt by Hindus. It was destroyed by Delhi Sultanate's army in 1299 CE.[8] The present temple was reconstructed in Chaulukya style of Hindu temple architecture and completed in May 1951.[9][10]

The Kashi Vishwanath Temple was repeatedly destroyed by Islamic invaders such as Qutb al-Din Aibak.

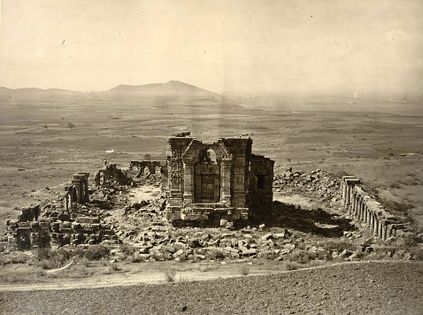

Ruins of the Martand Sun Temple. The temple was destroyed on the orders of Muslim Sultan Sikandar Butshikan in the early 15th century, with demolition lasting a year.

The armies of Delhi Sultanate led by Muslim Commander Malik Kafur plundered the Meenakshi Temple and looted it of its valuables.

Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins; one of the many temple complexes destroyed by the Delhi Sultanate.[11]

Rani ki vav is a stepwell, built by the Chaulukya dynasty, located in Patan; the city was sacked by Sultan of Delhi Qutb-ud-din Aybak between 1200 and 1210, and it was destroyed by the Allauddin Khilji in 1298.[11]

Artistic rendition of the Kirtistambh at Rudra Mahalaya Temple. The temple was destroyed by Alauddin Khalji.

Exterior wall reliefs at Hoysaleswara Temple. The temple was twice sacked and plundered by the Delhi Sultanate.[12]

تحطيم الأيقونات السياسي

Damnatio memoriae

Other examples

Other examples of political destruction of images include:

- There have been several cases of removing symbols of past rulers in Malta's history. Many Hospitaller coats of arms on buildings were defaced during the French occupation of Malta in 1798–1800; a few of these were subsequently replaced by British coats of arms in the early 19th century.[13] Some British symbols were also removed by the government after Malta became a republic in 1974. These include royal cyphers being ground off from post boxes,[14] and British coats of arms such as that on the Main Guard building being temporarily obscured (but not destroyed).[15]

- With the entry of the Ottoman Empire to the First World War, the Ottoman Army destroyed the Russian victory monument erected in San Stefano (the modern Yeşilköy quarter of Istanbul) to commemorate the Russian victory in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. The demolition was filmed by former army officer Fuat Uzkınay, producing Ayastefanos'taki Rus Abidesinin Yıkılışı—the oldest known Turkish-made film.

- In the late 18th century, the Brabant Revolutionaries sacked Brussels' Grand Place, destroying statues of nobility and symbols of Christianity.[16] In the 19th century, the place was renovated and many new statues added. In 1911, a marble commemoration for the Spanish freethinker and educator Francisco Ferrer, executed two years earlier and widely considered a martyr, was erected in the Grand Place. The statue depicted a nude man holding the Torch of Enlightenment. The Imperial German military, which occupied Belgium during the First World War, disliked the monument and destroyed it in 1915. It was restored in 1926 by the International Free Thought Movement.[17]

- In 1942 the pro-Nazi Vichy Government of France took down and melted Clothilde Roch's statue of the 16th-century dissident intellectual Michael Servetus, who had been burned at the stake in Geneva at the instigation of Calvin. The Vichy authorities disliked the statue, as it was a celebration of freedom of conscience. In 1960, having found the original molds, the municipality of Annemasse had it recast and returned the statue to its previous place.[18]

- The Battle of Baghdad and the regime of Saddam Hussein symbolically ended with the Firdos Square statue destruction, a U.S. military-staged event on April 9, 2003 where a prominent statue of Saddam Hussein was pulled down. Subsequently, statues and murals of Saddam Hussein all over Iraq were destroyed by US occupation forces as well as Iraqi citizens.[19]

- In 2016, paintings from the University of Cape Town were burned in student protests as symbols of colonialism.[20]

- In November 2019 the statue of Swedish footballer Zlatan Ibrahimović was vandalized by Malmö FF supporters after he announced he had become part-owner of Swedish rivals Hammarby. White paint was sprayed on it; threats and hateful messages towards Zlatan were written on the statue, and it was burned.[21][22] In a second attack the nose was sawed off and the statue was sprinkled with chrome paint.[23] On 5 January 2020 it was finally toppled.[24]

- On June 4, 2020, Virginia governor Ralph Northam ordered the monument to Robert E. Lee in Richmond to be removed in response to George Floyd protests. It was removed on September 8, 2021.[25]

انظر أيضاً

- Aniconism

- Censorship by religion

- Iconolatry

- List of destroyed heritage

- Lost artworks

- Natural theology

- Slighting

ملاحظات

الهامش

- ^ Aston, Margaret (1993), The King's Bedpost: Reformation and Iconography in a Tudor Group Portrait, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-48457-2.

- ^ Loach, Jennifer (1999), Bernard, George; Williams, Penry, eds., Edward VI, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, p. 187, ISBN 978-0-300-07992-0

- ^ Hearn, Karen (1995), Dynasties: Painting in Tudor and Jacobean England 1530–1630, New York: Rizzoli, pp. 75–76, ISBN 978-0-8478-1940-9, https://archive.org/details/dynastiespaintin00kare

- ^ "What happened to the Sphinx's nose?". Smithsonian Journeys. Smithsonian Institution. December 8, 2009.

- ^ Zivie-Coche, Christiane (2004). Sphinx : history of a monument. Ithaca : Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801489549 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg: The Chachnamah, An Ancient History of Sind, Giving the Hindu period down to the Arab Conquest. [1] Archived 2017-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sindhi Culture by U. T. Thakkur, Univ. of Bombay Publications, 1959.

- ^ Eaton, Richard M. (5 January 2001). "Temple desecration and Indo-Muslim states" (PDF). Frontline. Vol. 17, no. 26. The Hindu Group. p. 73 – via Columbia University, item 16 of the Table

{{cite magazine}}: External link in|issue= - ^ Gopal, Ram (1994). Hindu culture during and after Muslim rule: survival and subsequent challenges. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 148. ISBN 81-85880-26-3.

- ^ Jaffrelot, Christophe (1996). The Hindu nationalist movement and Indian politics: 1925 to the 1990s. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 84. ISBN 1-85065-170-1.

- ^ أ ب Eaton, Richard M. (1 September 2000). "Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States". Journal of Islamic Studies. Oxford University Press. 11 (3): 283–319. doi:10.1093/jis/11.3.283. ISSN 0955-2340.

- ^ Bradnock, Robert; Bradnock, Roma (2000). India Handbook. McGraw-Hill. p. 959. ISBN 978-0-658-01151-1.

- ^ Ellul, Michael (1982). "Art and Architecture in Malta in the Early Nineteenth Century" (PDF). Melitensia Historica. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2016.

- ^ Westcott, Kathryn (18 January 2013). "Letter boxes: The red heart of the British streetscape". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 November 2016.

- ^ Bonello, Giovanni (14 January 2018). "Mysteries of the Main Guard inscription". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018.

- ^ "La Grande-Place de Bruxelles" (in الفرنسية). bruNET. May 17, 2007. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ Avrich, Paul (1980). "The Martyrdom of Ferrer". The Modern School Movement: Anarchism and Education in the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 3–33. ISBN 978-0-691-04669-3. OCLC 489692159, p. 33.

- ^ Goldstone, Nancy Bazelon; Goldstone, Lawrence (2003). Out of the Flames: The Remarkable Story of a Fearless Scholar, a Fatal Heresy, and One of the Rarest Books in the World. New York: Broadway. pp. 313–316. ISBN 978-0-7679-0837-5.

- ^ Göttke, Florian. Toppled. Rotterdam: Post Editions, 2010.

- ^ Meintjies, Ilze-Marie (16 February 2016). "Protesting UCT Students Burn Historic Paintings, Refuse To Leave". Eyewitness News.

- ^ "Zlatan Ibrahimovic statue: Vandals try to saw through feet". BBC Sport. 12 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019 – via BBC News.

- ^ Daniels, Tim. "Zlatan Ibrahimovic's Malmo Statue Set on Fire After Becoming Hammarby Part Owner". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ Erberth, Nellie (December 22, 2019). "Zlatans staty vandaliserad igen – näsan avsågad". SVT Nyheter – via www.svt.se.

- ^ Wikén, Johan; Erberth, Nellie (January 5, 2020). "Zlatanstatyn vandaliserad igen – avsågad vid fötterna". SVT Nyheter – via www.svt.se.

- ^ Schneider, Gregory S.; Vozzella, Laura (2021-09-08). "Robert E. Lee statue is removed in Richmond, ex-capital of Confederacy, after months of protests and legal resistance". Washington Post. Retrieved 2021-09-08.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

وصلات خارجية

- Iconclasm in England, Holy Cross College (UK)

- Design as Social Agent at the ICA by Kerry Skemp, April 5, 2009

- Hindu temples destroyed by Muslim rulers in India

![The Somnath Temple in Gujarat was repeatedly destroyed by Islamic armies and rebuilt by Hindus. It was destroyed by Delhi Sultanate's army in 1299 CE.[8] The present temple was reconstructed in Chaulukya style of Hindu temple architecture and completed in May 1951.[9][10]](/w/images/thumb/f/f2/Somnath_temple_ruins_%281869%29.jpg/420px-Somnath_temple_ruins_%281869%29.jpg)

![Kakatiya Kala Thoranam (Warangal Gate) built by the Kakatiya dynasty in ruins; one of the many temple complexes destroyed by the Delhi Sultanate.[11]](/w/images/thumb/3/31/Warangal_fort.jpg/196px-Warangal_fort.jpg)

![Rani ki vav is a stepwell, built by the Chaulukya dynasty, located in Patan; the city was sacked by Sultan of Delhi Qutb-ud-din Aybak between 1200 and 1210, and it was destroyed by the Allauddin Khilji in 1298.[11]](/w/images/thumb/1/14/Rani_ki_vav1.jpg/402px-Rani_ki_vav1.jpg)

![Exterior wall reliefs at Hoysaleswara Temple. The temple was twice sacked and plundered by the Delhi Sultanate.[12]](/w/images/thumb/0/0e/Exteriors_Carvings_of_Shantaleshwara_Shrine_02.jpg/562px-Exteriors_Carvings_of_Shantaleshwara_Shrine_02.jpg)