مجموعة الخليلي للحج

| The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage | |

|---|---|

| |

| القيمون | Nasser D. Khalili (founder) Nahla Nassar (curator and registrar)[1] Qaisra Khan (curator)[2] |

| الحجم (عدد العناصر) | 5,000[2] |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

The Khalili Collection of the Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage is a private collection of around 5,000 items[2] relating to the Hajj, the pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca which is a religious duty in Islam. It is one of eight collections assembled, conserved, published and exhibited by the British-Iranian scholar, collector and philanthropist Nasser Khalili; each collection is considered among the most important in its field.[3] The collection's 300 textiles include embroidered curtains from the Kaaba, the Station of Abraham, the Mosque of the Prophet Muhammad and other holy sites, as well as textiles that would have formed part of pilgrimage caravans from Egypt or Syria. It also has illuminated manuscripts depicting the practice and folklore of the Hajj as well as photographs, art pieces, and commemorative objects relating to the Hajj and the holy sites of Mecca and Medina.

Part of the collection was exhibited at the British Museum in 2012 and it has lent objects for exhibition in other countries. It is documented in a ten-volume catalogue due to be published in 2022. Alongside the Topkapı Palace museum, it has been described as "the largest and most significant group of objects relating to the cultural history of the Hajj".

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Background: the Hajj

The Hajj (العربية: حَجّ) is an annual Islamic pilgrimage to the sacred city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia,[5] the holiest city for Muslims. Hajj is a mandatory religious duty for Muslims that must be carried out at least once in their lifetime by all adult Muslims who are physically and financially capable of undertaking the journey, and can support their family during their absence.[6][7][8]

Hajj is one of the Five Pillars of Islam, alongside Shahadah (confession of faith), Salat (prayer), Zakat (charity), and Sawm (fasting). The Hajj is a demonstration of the solidarity of the Muslim people, and their submission to God (Allah).[7][9] The word Hajj means "to attend a journey", which connotes both the outward act of a journey and the inward act of intentions.[10] In the centre of the Masjid al-Haram mosque in Mecca is the Kaaba, a cubic building known in Islam as the House of God.[11][6] The cloth covering of the Kaaba is known as the kiswah and is changed each year.[12] A Hajj consists of several distinct rituals including the tawaf (procession seven times counterclockwise round the Kaaba), wuquf (a vigil at Mount Arafat where Mohammed is said to have preached his last sermon), and ramy al-jamarāt (stoning of the Devil).[6][13]

The collection

The British-Iranian collector Nasser Khalili has assembled, conserved, published and exhibited eight art collections, including the largest private collection of Islamic art.[14][3] Patricia Scotland, Secretary-General of the Commonwealth of Nations, has described Khalili's collection as, alongside the Topkapı Palace museum in Istanbul, "the largest and most significant group of objects relating to the cultural history of the Hajj".[15] Baroness Amos, Director of the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, has described it as "the greatest collection of objects related to Makkah [Mecca] and the Hajj."[16] Its objects range from the 8th to the 20th century and from Morocco in the West to China in the East.[17]

In 2022 the publisher Assoulyne has released a 408-page volume documenting the collection's 5,000 objects, authored by one of the curators, Qaisra M. Khan.[18][19] The Hajj collection has been documented in a series of ten volumes which are due for publication in 2022.[2][20]

Objects in the collection

Textiles

The collection includes more than 300 textiles made for holy sites.[2] As well as the textiles themselves, the collection has archival material including ledgers and photographs from the Cairo workshops where the textiles are produced for Mecca and Medina.[2]

A mahmal is a passenger-less litter usually carried on a camel among a caravan of pilgrims. These would bear the name of the Ottoman ruler, symbolising their protection of the holy places.[21] The collection has seven mahmal coverings from caravans that would have set out from Egypt or Syria; the earliest was made in 17th century Istanbul at the request of Mehmed IV. Standing 355 centimetres (140 in) high, its silk is embroidered in silver and silver-gilt wire.[22][23] The most recent mahmal covering, from the end of the 19th century, bears the name of Abdul Hamid II.[22]

Other textiles include coverings used on the Kaaba, on the Prophet's Mosque in Medina, or in the Prophet's tomb.[2] Some served as bags for the key to the Kaaba.[2] The covering of the Kaaba, replaced annually, is known as the kiswah and the ornate curtain that covers its door is a sitarah, also known as a burdah or burqu'.[24] A sitarah for the Kaaba, 499 centimetres (196 in) high, dates from 1606. Made in Cairo, it was commissioned by Ahmed I.[25][26] Others, similarly embroidered with multiple verses from the Quran, were commissioned by Abdülmejid I[27][24] and Mahmud II.[28] The internal door of the Kaaba, the bab al-tawbah, has its own textile covering which was similarly made in Cairo and replaced annually. The collection has examples from the 19th and early 20th centuries.[29][30]

The Prophet's Mosque includes the tomb of Muhammad and, between the tomb and the minbar (pulpit), the Rawḍah ash-Sharifah (Noble Garden), carpeted in green. Sitarahs cover the minbar and some internal doors of the mosque, the metal grille around his tomb, and the doors of the Rawdah. The collection includes several of these sitarahs from the 18th century onwards.[2] A red silk sitarah 280 centimetres (110 in) high was made in Istanbul in the early 19th century. It bears the cartouche of Mahmud II who commissioned it for the Rawdah.[31][32] A section of curtain for the tomb, made in Istanbul in the 18th century, has calligraphed inscriptions in silver-wrapped silk thread on a deep red background.[33][34] This is one of eight surviving pieces of a single textile; another is in the collection of the Topkapı Palace in Istanbul.[35][33]

The Maqam Ibrahim (Station of Abraham) is a small square stone in the Masjid al-Haram mosque which, according to Islamic tradition, bears the footprint of Abraham.[36] It used to be housed in a structure that had its own kiswah (textile covering) made in Cairo and replaced every year, as happens now for the Kaaba. The collection includes a section from one such late-19th-century kiswah, 200 centimetres (79 in) high, of black silk with silver and gold wire embroidery.[37]

Talismanic cotton shirts are inked with prayers, quotes from the Quran, and schematic illustrations of the holy sanctuaries at Mecca and Medina, similar to what would appear on a pilgrimage certificate or illuminated manuscript.[38][39] One in the collection dates from the 16th or early 17th century[38] and another from the 18th or late 17th.[39] Others, from the 16th century and 17th century Ottoman Empire, are calligraphed with many names of Allah in bright colours as a kind of protection for the wearer.[40][41]

Talismanic shirt inscribed with Quranic verses, the Asma’ al-Husna, and prayers along with depictions of the two holy sanctuaries. Turkey, 18th century

Manuscripts and miniature paintings

The collection includes a folio from a 16th-century manuscript of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh (Book of Kings), depicting Alexander the Great kneeling in prayer at the Kaaba among other pilgrims.[42][43] He is often portrayed in Islam as having performed a Hajj.[42][43]

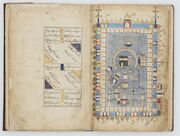

Anis Al-Hujjaj (Pilgrim's Companion) is a seventeenth century account of a Hajj undertaken in 1677 by Safi ibn Vali, an official of the Mughal court. The document gives advice to pilgrims about the journey. As well as showing diagrams of the routes and places of the Hajj, the illustrations colourfully depict the pilgrims travelling, living together in camps, and taking part in the Hajj rites.[44] The Khalili collection includes an exemplar, thought to originate from Gujarat, which consists of 23 folios including nine half-page and eleven full-page illustrations.[45] Another illuminated guide for pilgrims is the Futuh al-Haramayn of Muhi Al-Din Lari; the collection has exemplars from 16th century Mecca and late 18th or 19th century India.[46][47]

Although it is rare for Qurans to include depictions of the holy sites of Mecca and Medina, the collection includes examples from the late 18th century that do so.[48][49][50] The Dala'il al-Khayrat by Muhammad al-Jazuli is a very popular prayer book. The collection includes multiple exemplars, illuminated with diagrams of holy sites.[51][52][53][54][55] A late 18th or early 19th century exemplar is presumably the source of a pair of detached pages depicting the holy sanctuaries of Mecca and Medina.[56][57]

Another illuminated manuscript, consisting of 35 folios, sets out the family tree of the Prophet Mohammed with additional text about his life and companions. It dates from the 14th century Middle East, possibly Syria.[58] A 16th century pilgrimage scroll from the Hejaz region records the rites an unnamed pilgrim conducted, combined with diagrams of the Prophet's tomb and other locations visited.[59]

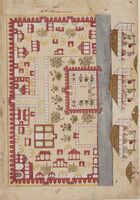

Folio from Anis Al-Hujjaj showing a plan of the port of Surat. Possibly Gujarat, circa 1677–80

The Great Mosque depicted in the Futuh al-Haramayn, 1582

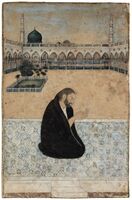

The Sufi saint Mian Mir praying at Medina. India, 18th century

Illustrations

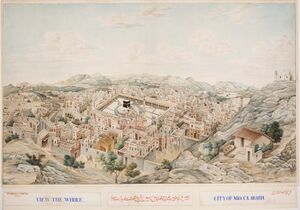

A panoramic view of Mecca dating from around 1845 is the earliest known accurate depiction of the area around the Masjid al-Haram.[60] The painter, Muhammad ‘Abdallah of Delhi, was the grandson of Mazar ‘Ali Khan, court artist for Bahadur Shah II, the last Mughal Emperor.[4][60] An earlier, largely inaccurate, representation of Mecca and Medina is given in a 1727 album of architectural drawings by the Austrian architect Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach.[61] A detached plate, carefully hand-coloured, from an 1825 edition of George Sale's English translation of the Quran, gives a plan and view of the Holy Sanctuary in Mecca.[62]

Photographs

The collection includes a set of the earliest known photographs of Mecca and the Hajj, taken by Muhammad Sadiq, an Egypt-born photographer who was also treasurer of the Egyptian Hajj caravan. In 1880 and 1881, Muhammad Sadiq used glass plate photography to capture the Kaaba and other holy sites in Mecca, Medina, Mount Arafat, and Mina.[63][64][4] Other photographers in the collection include Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje, the first European to photograph Mecca[65] and Abd al-Ghaffar, a Meccan doctor who was the first local person to photograph the Great Mosque.[66][67] Safouh Izzat Naamani (1926–2015) was the first to photograph Mecca from the air and the collection includes an aerial photograph from 1966, showing the then-new covering of the Safa and Marwa hills that pilgrims process between.[68][69]

Art inspired by the Hajj has continued into the 21st century. One such work is the series of photogravure etchings by the artist Ahmad Mater titled Magnetism I–IV. Using iron filings and magnets, Mater created a scene centered on a black cube which visually evokes the pilgrims walking around the Kaaba.[70][71]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Coins and medals

The coins in the collection range from the Abbasid period of the 7th century to modern times.[72] Many were struck in Mecca or elsewhere in Saudi Arabia.[2] The oldest is a gold dinar from 105 AH (723-4 AD) struck in "the mine of the Commander of the Faithful in the Hijaz".[73]

Other objects

Other kinds of object in the collection were used during a pilgrimage, depict the holy sites, or otherwise celebrate the Hajj. There are water flasks carried by pilgrims, and Hajj certificates.[2] There are scientific instruments including qibla compasses (for finding the direction of Mecca) decorated with diagrams of the Kaaba.[74][4] There are hilyes (calligraphic artworks relating the attributes of the Prophet Mohammed) from Ottoman Turkey.[75][76][77] After independence in 1947, the State Bank of Pakistan issued Hajj banknotes. These made currency conversion easier for pilgrims and gave the banks more control over their currency. The collection has examples from Pakistan and India.[78][79]

Qibla compass, Istanbul, 18th – early 19th century

Chamfron (for a horse's face) with cheek-pieces. Ottoman Turkey or Egypt, 18th century

Publications

A single-volume summary of the collection by Qasira Khan, with 300 illustrations, was published in 2022 by Assouline Publishing.[80][81] An eleven-volume catalogue is scheduled for publication in 2023.[82]

Exhibitions

The collection is not on permanent public display, but was the largest lender of objects to a 2012 exhibition about the Hajj at the British Museum.[83] Objects have subsequently been lent to exhibitions in other countries.[2]

- January – April 2012: Hajj: Journey to the Heart of Islam, British Museum, London, UK[84]

- March – June 2012: Gifts of the Sultan. The Arts of Giving at the Islamic Courts, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar

- September 2013 – March 2014: Longing for Mecca: The Pilgrim’s Journey, Rijksmuseum Volkenkunde, Leiden, the Netherlands[1] (more than 80 items from the collection)[72]

- April – August 2014: Hajj: le pèlerinage à La Mecque, Arab World Institute , Paris, France (40 items from the collection)[72]

- September 2017 – March 2018: Hajj: Memories of a Journey, Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque, Abu Dhabi, UAE

- February 2019 – January 2020: Longing for Mecca, Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, the Netherlands[1][3]

Digitisation

In 2021, a dozen objects in the collection were digitised by Google Arts & Culture, creating gigapixel images. These were combined with the collection's own digital images to produce an online exhibit in which readers can zoom in on very fine details.[85]

References

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0 The Khalili Collections, Khalili Foundation,

To learn how to add open-license text to Wikipedia articles, please see Wikipedia:Adding open license text to Wikipedia.

For information on reusing text from Wikipedia, please see the terms of use.

- ^ أ ب ت "The Eight Collections". Nasser D. Khalili. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س "Hajj and The Arts of Pilgrimage". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2021-02-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ أ ب ت "The Khalili Collections major contributor to "Longing for Mecca" exhibition at the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam". UNESCO. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 16 April 2019. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Khalili, Nasser (2017). "A History of the Hajj in Ten Objects". Holy Makkah: a Celebration of Unity. London: FIRST. ISBN 9780995728141.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)[dead link] - ^ Mohammad Taqi al-Modarresi (26 March 2016). The Laws of Islam (PDF). Enlight Press. p. 471. ISBN 978-0-9942409-8-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت Long, Matthew (2011). Islamic Beliefs, Practices, and Cultures. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-7614-7926-0. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ أ ب Nigosian, S. A. (2004). Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 110–111. ISBN 0-253-21627-3.

- ^ Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs - Islam Archived 2 أكتوبر 2011 at the Wayback Machine See drop-down essay on "Islamic Practices"

- ^ Hooker, M. B. (2008). Indonesian Syariah: Defining a National School of Islamic Law. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 228. ISBN 978-981-230-802-3. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Adelowo, E. Dada, ed. (2014). Perspectives in Religious Studies: Volume III. Ibadan: HEBN Publishers Plc. p. 395. ISBN 978-978-081-447-2.

- ^ Wensinck, Arent Jan (1978). "Kaʿba". In van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch.; Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IV: Iran–Kha. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 317–322. ISBN 90-04-05745-5.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Ghazal, Rym (28 August 2014). "Woven with devotion: the sacred Islamic textiles of the Kaaba". The National. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ^ Zaki, Yousra (7 August 2019). "What is Hajj? A simple guide to Islams annual pilgrimage". gulfnews.com. GN Media. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The Khalili Family Trust | Collections Online | British Museum". www.britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 2020-06-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Scotland, Patricia (2017). "Foreword". Holy Makkah: a Celebration of Unity. London: FIRST. ISBN 9780995728141. Archived from the original on 2021-03-16. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- ^ Bokova, Irina (2017). "The Preservation of Heritage". Holy Makkah: A Celebration of Unity. London: FIRST. p. 71. ISBN 9780995728141. Archived from the original on 2020-10-08. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

- ^ "Khalili Family Trust – Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage Collection". Discover Islamic Art. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Harris, Gareth (2022-05-03). "May Book Bag: from the Hirshhorn Museum's collection catalogue to Tom of Finland's sketches of bulging, er, muscles". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ LeFevre, Camille (2022-06-02). "New Titles from Assouline Take a Global Perspective". Midwest Home. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ "Hajj and The Arts of Pilgrimage Volume X". Khalili Collections. Archived from the original on 2021-01-16. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ "Mahmal". Textile Research Centre, Leiden. 3 October 2016. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ أ ب "A Complete Cover for a Damascus Mahmal". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Nassar, Nahla. "A complete cover for a Damascus mahmal, with the name of Sultan Mehmed IV". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ أ ب Nassar, Nahla (2020). "Curtain for the door of the Ka'ba, with the name of Sultan Abdülmecid ['Abd al-Majid] I". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Nassar, Nahla (2020). "Curtain for the door of the Ka'ba, with the name of Sultan Ahmed I". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Curtain for Door of the Ka'bah". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Curtain for the Door of the Ka'bah". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Sitarah for the Door of the Ka'aba". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Curtain for the Internal Door of the Ka'bah (the Bab al-Tawbah)". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Curtain for the Internal Door of the Ka'bah (the Bab al-Tawbah)". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Sitarah for the Rawdah of the Prophet's Mosque in Medina". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Nassar, Nahla (2020). "Sitara for the rawda of the Prophet's mosque in Medina". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ أ ب "Section from the kiswa of the Prophet's tomb". Explore Islamic Art Collections. 2020. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Section from a Kiswah of the Prophet's tomb". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ İpek, Seli̇n (2006). "Ottoman Ravza-I Mutahhara Covers Sent from Istanbul to Medina with the Surre Processions". Muqarnas. 23: 305. doi:10.1163/22118993_02301013. ISSN 0732-2992. JSTOR 25482446.

- ^ Peters, F. E. (1994). "Another Stone: The Maqam Ibrahim". The Hajj. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9780691026190.

- ^ "Section from the Kiswah of Maqam Ibrahim". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ أ ب "Talismanic Shirt with Depictions of the Two Holy Sanctuaries". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ أ ب Nassar, Nahla (2020). "Talismanic shirt". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Munroe, Nazanin Hedayat (2019-01-02). "Wrapped Up: Talismanic Garments in Early Modern Islamic Culture". Journal of Textile Design Research and Practice. 7 (1): 4–24. doi:10.1080/20511787.2019.1586316. ISSN 2051-1787. S2CID 218837104.

- ^ "Talismanic shirt". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ أ ب Webb, Peter (2013). "The Hajj before Muhammad: Journeys to Mecca in Muslim Narratives of Pre-Islamic History". In Porter, Venetia; Saif, Liana (eds.). The Hajj: collected essays. London: The British Museum. p. 12. ISBN 9780861591930.

- ^ أ ب "'Alexander Visits the Ka'bah', Folio from a Copy of Firdawsi's Shahnamah". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Agius, Dionisius A. (2013). "Ships that Sailed the Red Sea in Medieval and Early Modern Islam: Perception and Reception". In Porter, Venetia; Saif, Liana (eds.). The Hajj: collected essays. London: The British Museum. p. 93. ISBN 9780861591930.

- ^ Nassar, Nahla (2020). "The Anis al-Hujjaj ('Pilgrims' Companion') of Safi ibn Vali". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Futuh al-Haramayn (a Handbook for Pilgrims to Mecca and Medina) of Muhyi Lari". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Futuh al-Haramayn (a Handbook for Pilgrims to Mecca and Medina) of Muhyi al-Din Lari". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Single-Volume Qur'an with Depictions of the Two Holy Sanctuaries". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "A single-volume Qur'an with depictions of Mecca and Medina". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Single-volume Qur'an with a Depiction of the Holy Sanctuary at Mecca". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Nassar, Nahla (2020). "The Dala'il al-khayrat of al-Jazuli". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "An Exceptional Copy of al-Jazuli's Dala'il al-Khayrat". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The Dala'il al-Khayrat of al-Jazuli and Other Prayers". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "A Lavishly Illuminated Copy of al-Jazuli's Dala'il al-Khayrat". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Dala'il al-Khayrat of al-Jazuli". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Nassar, Nahla (2020). "The Holy Sanctuaries at Mecca and Medina". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The Masjid al-Haram at Mecca and the Prophet's Mosque at Medina". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "A Genealogy of the Prophet Muhammad". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Section from a Pilgrimage Scroll". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ أ ب "Panoramic view of the city of Mecca, painted by Muhammad 'Abdallah, the Delhi cartographer". Explore Islamic Art Collections. 2020. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Khan, Qaisra (2020). "An illustrated album of architecture, including views of Mecca and Medina". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Khan, Qaisra (2020). "Plan and view of the Holy Sanctuary at Mecca, published by Thomas Tegg, London 1825". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Bell, Jennifer (2019-05-03). "How an Arab took Makkah's first photos". Arab News. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Khan, Qaisra (2020). "Photographic views of Hajj, by Muhammad Sadiq Bey". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Photographic View of Mecca". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Khan, Qaisra (2020). "Photographic view entitled Prayers around the Ka'ba". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Photographic View of the Masjid al-Haram". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The Masjid al-Haram". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Khan, Qaisra (2020). "Photographic view of Mecca". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Magnetism I – IV". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Khan, Qaisra (2020). "Magnetism I - IV (Photogravure), 2012". Explore Islamic Art Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ أ ب ت "Hajj and The Arts of Pilgrimage (700-2000)". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Umayyad Gold Dinar". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Qiblah Compass". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Hilyah (Hilye-i Sherife)". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Hilyah of the Prophet Muhammad". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Hilyah, Combined with the Relics of the Prophet". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "10 Rupee Hajj Banknote". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "100 Rupee Hajj banknote". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-12-16.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Maisey, Sarah (2022-07-11). "New book shows 300 illustrations of the Hajj pilgrimage over the centuries". The National. Retrieved 2022-12-06.

- ^ "Book illustrating 300 photos of Hajj pilgrimage over the centuries published". irandaily.ir. 12 July 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-06.

- ^ "Hajj and The Arts of Pilgrimage". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2022-12-06.

- ^ Akbar, Arifa (30 January 2012). "Pilgrim's progress: Journey to the Heart of Islam". The Independent. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Arab, Pooyan Tamimi (2020-05-26). "Longing for Mecca (Verlangen naar Mekka): Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam (february 2019 – january 2020)". Material Religion. 16 (3): 394–396. doi:10.1080/17432200.2020.1775420. ISSN 1743-2200.

- ^ "High-Res Hajj". BBC Click. 21 July 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

External links

- Official website

- Hajj: a Cultural History – online exhibition

- A Visual History of the Hajj: exhibit at Google Arts & Culture

- Short video about the collection

- CS1 maint: url-status

- Articles with dead external links from May 2023

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing explicitly cited عربية-language text

- Free-content attribution

- Hajj

- Islamic pilgrimages

- Culture in Mecca

- Medina

- Islamic art

- Khalili Collections