مبدأ فرما

Fermat's principle, also known as the principle of least time, is the link between ray optics and wave optics. In its original "strong" form,[1] Fermat's principle states that the path taken by a ray between two given points is the path that can be traversed in the least time. In order to be true in all cases, this statement must be weakened by replacing the "least" time with a time that is "stationary" with respect to variations of the path — so that a deviation in the path causes, at most, a second-order change in the traversal time. To put it loosely, a ray path is surrounded by close paths that can be traversed in very close times. It can be shown that this technical definition corresponds to more intuitive notions of a ray, such as a line of sight or the path of a narrow beam.

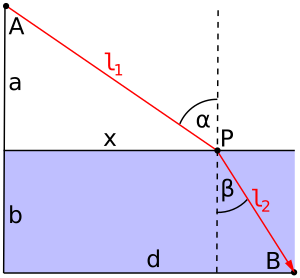

First proposed by the French mathematician Pierre de Fermat in 1662, as a means of explaining the ordinary law of refraction of light (Fig. 1), Fermat's principle was initially controversial because it seemed to ascribe knowledge and intent to nature. Not until the 19th century was it understood that nature's ability to test alternative paths is merely a fundamental property of waves.[2] If points A and B are given, a wavefront expanding from A sweeps all possible ray paths radiating from A, whether they pass through B or not. If the wavefront reaches point B, it sweeps not only the ray path(s) from A to B, but also an infinitude of nearby paths with the same endpoints. Fermat's principle describes any ray that happens to reach point B; there is no implication that the ray "knew" the shortest path or "intended" to take that path.

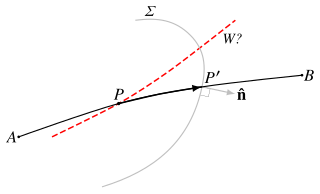

For the purpose of comparing traversal times, the time from one point to the next nominated point is taken as if the first point were a point-source.[3] Without this condition, the traversal time would be ambiguous; for example, if the propagation time from P to P′ were reckoned from an arbitrary wavefront W containing P (Fig. 2), that time could be made arbitrarily small by suitably angling the wavefront.

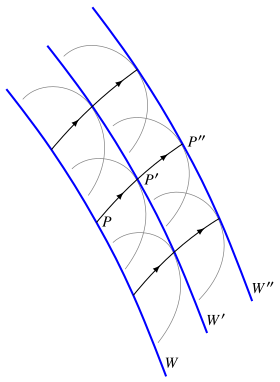

Treating a point on the path as a source is the minimum requirement of Huygens' principle, and is part of the explanation of Fermat's principle. But it can also be shown that the geometric construction by which Huygens tried to apply his own principle (as distinct from the principle itself) is simply an invocation of Fermat's principle.[4] Hence all the conclusions that Huygens drew from that construction — including, without limitation, the laws of rectilinear propagation of light, ordinary reflection, ordinary refraction, and the extraordinary refraction of "Iceland crystal" (calcite) — are also consequences of Fermat's principle.

الاستنتاج

Equivalence to Huygens' construction

In this article we distinguish between Huygens' principle, which states that every point crossed by a traveling wave becomes the source of a secondary wave, and Huygens' construction, which is described below.

النسخة الحديثة

الصياغة كدالة في معامل الانكسار

Let a path Γ extend from point A to point B. Let s be the arc length measured along the path from A, and let t be the time taken to traverse that arc length at the ray speed (that is, at the radial speed of the local secondary wavefront, for each location and direction on the path). Then the traversal time of the entire path Γ is

-

(1)

(where A and B simply denote the endpoints and are not to be construed as values of t or s). The condition for Γ to be a ray path is that the first-order change in T due to a change in Γ is zero; that is,

- .

العلاقة بمبدأ هاملتون

If x,y,z are Cartesian coordinates and an overdot denotes differentiation with respect to s , Fermat's principle (2) may be written[5]

In the case of an isotropic medium, we may replace nr with the normal refractive index n(x,y,z), which is simply a scalar field. If we then define the optical Lagrangian[6] as

Fermat's principle becomes[7]

- .

If the direction of propagation is always such that we can use z instead of s as the parameter of the path (and the overdot to denote differentiation w.r.t. z instead of s), the optical Lagrangian can instead be written[8]

so that Fermat's principle becomes

- .

This has the form of Hamilton's principle in classical mechanics, except that the time dimension is missing: the third spatial coordinate in optics takes the role of time in mechanics.[9] The optical Lagrangian is the function which, when integrated w.r.t. the parameter of the path, yields the OPL; it is the foundation of Lagrangian and Hamiltonian optics.[10]

التاريخ

فرما مقابل الكارتيزيين

If a ray follows a straight line, it obviously takes the path of least length. هيرون السكندري، في كتابه Catoptrics (1st century CE), showed that the ordinary law of reflection off a plane surface follows from the premise that the total length of the ray path is a minimum.[12] In 1657, Pierre de Fermat received from Marin Cureau de la Chambre a copy of newly published treatise, in which La Chambre noted Hero's principle and complained that it did not work for refraction.[13]

غفلة هويگنز

لاپلاس و ينگ و فرنل و لورنتس

پيير-سيمون لاپلاس (1749–1827)

توماس ينگ (1773–1829)

أوگوستان-جان فرنل (1788–1827)

هندريك لورنتس (1928–1853)

انظر أيضاً

Notes

References

- ^ Cf. Born & Wolf, 1970, p. 740.

- ^ Cf. Young, 1809, p. 342; Fresnel, 1827, tr. Hobson, pp. 294–6, 310–11; De Witte, 1959, p. 293n.

- ^ De Witte (1959) invokes the point-source condition at the outset (p. 294, col. 1).

- ^ De Witte (1959) gives a proof based on calculus of variations. The present article offers a simpler explanation.

- ^ Cf. Chaves, 2016, pp. 568–9.

- ^ Chaves, 2016, p. 581.

- ^ Chaves, 2016, p. 569.

- ^ Cf. Chaves, 2016, p. 577.

- ^ Cf. Born & Wolf, 1970, pp. 734–5,741; Chaves, 2016, p. 669.

- ^ Chaves, 2016, ch. 14.

- ^ F. Katscher (May 2016), When Was Pierre de Fermat Born?, https://www.maa.org/press/periodicals/convergence/when-was-pierre-de-fermat-born, retrieved on 22 August 2019.

- ^ Sabra, 1981, pp. 69–71. As the author notes, the law of reflection itself is found in Proposition XIX of Euclid's Optics.

- ^ Sabra, 1981, pp. 137–9; Darrigol, 2012, p. 48.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "vanHouten-beenakker-1995-272" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "clerselier-1662" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "fermat-1662-clerselier" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "feynman-1988-51" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "laplace-1809" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "lipsons" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "lorentz-1907" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "ogborn-taylor-2005" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "schuster-2000-261" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "smith-1959-651n" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

خطأ استشهاد: الوسم <ref> ذو الاسم "veselago-2002-1099" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.

<ref> ذو الاسم "zyga-2013" المُعرّف في <references> غير مستخدم في النص السابق.ببليوگرافيا

- M. Born and E. Wolf, 1970, Principles of Optics, 4th Ed., Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- J. Chaves, 2016, Introduction to Nonimaging Optics, 2nd Ed., Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-4822-0674-6.

- O. Darrigol, 2012, A History of Optics: From Greek Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century, Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-964437-7.

- A.J. de Witte, 1959, "Equivalence of Huygens' principle and Fermat's principle in ray geometry", American Journal of Physics, vol. 27, no. 5 (May 1959), pp. 293–301, DOI:10.1119/1.1934839. Erratum: In Fig. 7(b), each instance of "ray" should be "normal" (noted in vol. 27, no. 6, p. 387).

- E. Frankel, 1974, "The search for a corpuscular theory of double refraction: Malus, Laplace and the price [ك] competition of 1808", Centaurus, vol. 18, no. 3 (September 1974), pp. 223–245, DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0498.1974.tb00298.x.

- A. Fresnel, 1827, "Mémoire sur la double réfraction", Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences de l'Institut de France, vol. VII (for 1824, printed 1827), pp. 45–176; reprinted as "Second mémoire…" in Oeuvres complètes d'Augustin Fresnel, vol. 2 (Paris: Imprimerie Impériale, 1868), pp. 479–596; translated by A.W. Hobson as "Memoir on double refraction", in R. Taylor (ed.), Scientific Memoirs, vol. V (London: Taylor & Francis, 1852), pp. 238–333. (Cited page numbers are from the translation.)

- C. Huygens, 1690, Traité de la Lumière (Leiden: Van der Aa), translated by S.P. Thompson as Treatise on Light, University of Chicago Press, 1912; Project Gutenberg, 2005. (Cited page numbers match the 1912 edition and the Gutenberg HTML edition.)

- P. Mihas, 2006, "Developing ideas of refraction, lenses and rainbow through the use of historical resources", Science & Education, vol. 17, no. 7 (August 2008 [ك]), pp. 751–777 (online 6 September 2006), DOI:10.1007/s11191-006-9044-8.

- I. Newton, 1730, Opticks: or, a Treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections, and Colours of Light, 4th Ed. (London: William Innys, 1730; Project Gutenberg, 2010); republished with Foreword by A. Einstein and Introduction by E.T. Whittaker (London: George Bell & Sons, 1931); reprinted with additional Preface by I.B. Cohen and Analytical Table of Contents by D.H.D. Roller, Mineola, NY: Dover, 1952, 1979 (with revised preface), 2012. (Cited page numbers match the Gutenberg HTML edition and the Dover editions.)

- A.I. Sabra, 1981, Theories of Light: From Descartes to Newton (London: Oldbourne Book Co., 1967), reprinted Cambridge University Press, 1981, ISBN 0-521-28436-8.

- A.E. Shapiro, 1973, "Kinematic optics: A study of the wave theory of light in the seventeenth century", Archive for History of Exact Sciences, vol. 11, no. 2/3 (June 1973), pp. 134–266, DOI:10.1007/BF00343533.

- T. Young, 1809, Article X in the Quarterly Review, vol. 2, no. 4 (November 1809), pp. 337–48.

- A. Ziggelaar, 1980, "The sine law of refraction derived from the principle of Fermat — prior to Fermat? The theses of Wilhelm Boelmans S.J. in 1634", Centaurus, vol. 24, no. 1 (September 1980), pp. 246–62, DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0498.1980.tb00377.x.

للاستزادة

- A. Bhatia (26 March 2014), To save drowning people, ask yourself 'What would light do?', http://nautil.us/blog/to-save-drowning-people-ask-yourself-what-would-light-do, retrieved on 7 August 2019.

- J.Z. Buchwald, 1989, The Rise of the Wave Theory of Light: Optical Theory and Experiment in the Early Nineteenth Century, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-07886-8, especially pp. 36–40.

- M.G. Katz; D.M. Schaps; S. Shnider (2013), "Almost Equal: the method of adequality from Diophantus to Fermat and beyond", Perspectives on Science 21 (3): 283–324, Bibcode: 2012arXiv1210.7750K.

- M.S. Mahoney (1994), The Mathematical Career of Pierre de Fermat, 1601–1665, 2nd Ed., Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-03666-7.

- R. Marqués; F. Martín; M. Sorolla, 2008 (reprinted 2013), Metamaterials with Negative Parameters: Theory, Design, and Microwave Applications, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, ISBN 978-0-471-74582-2.

- J.B. Pendry and D.R. Smith (2004), "Reversing Light With Negative Refraction", Physics Today, 57 (6): 37–43, DOI:10.1063/1.1784272.