كشوح

| كشوح Kušuḫ | |

|---|---|

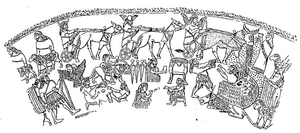

An ancient Anatolian depiction of the moon god Arma, displaying iconography patterned after Kušuḫ's.[1] متحف الحضارات الأناضولية، أنقرة. | |

| أسماء أخرى | أومبو[2] |

| مركز العبادة الرئيسي | Šuriniwe,[3] possibly Kuzina (Harran?)[4] |

| القرين | نيكال |

| الأنجال | |

| الآلهة المكافئة | |

| المكافئ Mesopotamian | سين |

| المكافئ Ugaritic | يرخ |

| المكافئ اللوڤي | أرما |

| المكافئ Hattian | كشكو |

كشوح Kušuḫ، ويُعرف أيضاً بالاسم أومبو Umbu،[2] was the god of the moon in Hurrian pantheon. He is attested in cuneiform texts from many sites, from Hattusa in modern Turkey, through Ugarit, Alalakh, Mari and other locations in Syria, to Nuzi, located near modern Kirkuk in Iraq, but known sources do not indicate that he was associated with a single city. His name might be derived from the toponym Kuzina, possibly the Hurrian name of Harran, a city in Upper Mesopotamia, but both this etymology and identification of this sparsely attested place name remain uncertain. He was a popular, commonly worshiped god, and many theophoric names invoking him are known. In addition to serving as a divine representation of the moon, he was also associated with oaths, oracles and pregnancy. Some aspects of his character were likely influenced by his Mesopotamian counterpart Sin, while he in turn was an influence on the Ugaritic god Yarikh and Luwian Arma.

In Hurrian mythology, Kušuḫ appears as one of the allies of the weather god Teššub in his struggle against Kumarbi, but known compositions do not provide much information about his individual characteristics. It has also been proposed that the Ugaritic composition Marriage of Nikkal and Yarikh was based on a Hurrian myth about Kušuḫ, well attested as the husband of this goddess.

الاسم

Kušuḫ, usually written dKu-uš-uḫ in cuneiform,[7] was the primary name of the Hurrian moon god.[2] There is no agreement if transcriptions of Hurrian words should reflect theories about the possible presence of voiced and unvoiced consonants in them; conventional spelling of Kušuḫ's name in modern publications reflects the view that leaving the disputed ones unvoiced is preferable.[8] The alternate spelling Kušaḫ is attested in Alalakh and uncommonly in texts from Hattusa.[9] According to Manfred Krebernik the form Ušu is also known, though he does not list the location where sources it occurs in were found.[10] Two separate writings of Kušuḫ's name in the Ugaritic alphabetic script are attested, kḏġ and kzġ,[11] vocalized as Kuḏuġ and Kuzuġ, respectively.[12]

In addition to these spellings, the name could be also represented by the logograms d30 (the numeral associated with the moon[13]) and dEN.ZU, like that of the Mesopotamian moon god Sin.[14] For example, according to Gary Beckman Kušuḫ might be among the deities designated by the former logogram in texts from Emar.[15] Forms combining logographic and phonetic versions, d30-uḫ and dEN.ZU-uḫ, are also known.[7]

It has been proposed that Kušuḫ's name is an adjective derived from the toponym Kuzina,[9][16] possibly the Hurrian name of Harran.[1] However, in the treaty between Šuppiluliuma I and Šattiwaza, Kušuḫ and the moon god of Harran appear as two separate deities.[9][17] It has also been noted that Kuzina is only known from a single attestation in the so-called Tale of Appu, whose Hurrian origin is disputed, and researchers such as Itamar Singer consider it to have Hittite roots instead, though this view is not universally accepted either.[18] This text does mention that a moon god was believed to reside in Kuzina,[19] though according to Volkert Haas Arma might be the deity meant.[20] At the same time, he does find the theory that Kuzina was the Hurrian name of Harran plausible.[4]

Umbu

In addition to Kušuḫ, a secondary name of the moon god in Hurrian sources was Umbu,[2] also spelled Umpu, Umpa and Umpi.[21] It might have been originally in use somewhere in Syria or southern Anatolia as a part of a distinct local tradition, which would mean it only came to be adopted by the Hurrians at some point in their history.[22][2] However, it is also possible that it has Hurrian origin, as a root umb- (meaning presently unknown), is attested in the Hurrian language.[23] It has been proposed that Umbu functioned as the name of a specific manifestation of Kušuḫ, perhaps representing the full moon, though this remains speculative.[2]

Mauro Giorgieri notes that attestations of Umbu as a fully independent deity are uncommon, and that he almost always appears alongside Nikkal.[21] In early scholarship it was assumed that Umbu was an appellative referring to Nikkal, analogous to the second element in the full Ugaritic form of her name, Nikkal-wa-Ib, but according to Giorgieri this is not plausible in the light of more recent research.[23] The latter epithet is most likely a cognate of either Akkadian inbu, "fruit," or ebbu, "bright" or "pure," rather than Umbu's name.[23]

Character and iconography

Kušuḫ was functioned as the good of the moon in the Hurrian pantheon.[24] It is possible that his character was at least in part influenced by that of his Mesopotamian counterpart, Sin.[25] Like him, he was associated with pregnancy, and could be invoked in birth incantations.[2] However, a well attested role of Kušuḫ which according to Gernot Wilhelm sets him apart from his Mesopotamian counterpart was that of a protector of oaths, otherwise commonly associated with underworld deities in Hurrian culture.[9] Ugaritic texts refer to him as the "king of the (oracular) decisions" as well, marking him as a deity associated with oracles.[11]

A depiction of Kušuḫ is known from the reliefs showing a procession of deities in the Yazılıkaya sanctuary, with the figure representing him being assigned the number 35 in scholarly treatments of this site.[26] He is depicted as winged, and his pointed cap is adorned with a lunar crescent.[27] A possible artistic portrayal of Kušuḫ has also been identified on the golden bowl of Hasanlu, sometimes assumed to be a late example of art inspired by motifs from Hurrian mythology, on which a moon god is shown traveling in a chariot drawn by mules.[13][24]

Associations with other deities

Family and court

Kušuḫ 's wife was Nikkal, derived from the Mesopotamian goddess Ningal.[9] Umbu, either an alternate name of Kušuḫ or a separate deity assimilated with him, appears alongside Nikkal in Hurrian texts too.[2] In Ugarit, she was recognized as the wife of both Kušuḫ and the local god Yarikh,[22] but since she is best attested in texts written in Hurrian rather than in Ugaritic, Gabriele Theuer concludes that she was most likely only introduced to the city by the Hurrians.[28] She also reached the Hittite pantheon through Hurrian mediation.[2] Kušuḫ was also associated with Ishara due to their shared role as divine protectors of oaths.[4] Piotr Taracha points out that it might be significant that she was already linked with another lunar god, Saggar, in the third millennium BCE in Ma-NEki, as attested in texts from Ebla.[29]

A passage labeling Teššub as a son of Kušuḫ is known,[30] but as it is entirely isolated and no further known documents refer to such a connection between these two gods, Daniel Schwmer remarks that it is difficult to evaluate its significance.[6] In a tradition most likely influenced by Mesopotamian views on divine genealogy, Šauška, usually the sister of Teššub, was regarded as the daughter of the moon god too.[5]

It has been proposed by Meindert Dijkstra that the god Tapšuwari was regarded as the sukkal (attendant deity) of Kušuḫ,[31] though he has also been interpreted as one of the members of the circle of Kumarbi.[32] Attestations of Tapšuwari are limited to a single fragment of the Hurrian version of the myth Song of Ullikummi, and a single other literary passage, both of which also mention Kušuḫ.[32]

Other lunar gods

Kušuḫ was regarded as the Hurrian counterpart of Mesopotamian Sin.[30] In Ugarit, he was additionally regarded as analogous to Yarikh.[33] However, in the ritual KTU3 1.111 the two moon gods, accompanied by Nikkal, appear together and receive separate offerings, with instructions pertaining to Kušuḫ (and Nikkal) written in Hurrian, and these instead referring to Yarikh - in Ugaritic, possibly reflecting the bilingualism of the scribe.[34]

Especially in Kizzuwatna, the character of the Luwian moon god Arma were heavily influenced by Kušuḫ's.[1] He also came to be portrayed identically to his Hurrian counterpart, in a pointed cap with a crescent symbol and with wings on his shoulders.[1]

Kušuḫ s name is sometimes linked by researchers with that of the Hattian moon god, conventionally assumed to bear the name Kašku, which might point at early contact between speakers of Hurrian and Hattic.[9] However, Daniel Schwemer notes that it is possible the Hattian god was instead named Kab, as suggested in a recent alternate reading of the same passage on which the older assumption about his name relies.[2]

Worship

Kušuḫ was a high-ranking, commonly worshiped god,[35] and he is regarded by researchers as one of the "pan-Hurrian" deities, present in the pantheons of all areas where the Hurrian language was in use, from Kizzuwatna in modern Turkey to the Zagros Mountains, similar to Teššub, Šauška, Kumarbi or Nabarbi.[9][36][37] He appears in theophoric names from both eastern and western Hurrian cities.[38] Examples include Eḫlip-Kušuḫ ("Kušuḫ saves"), attested in Mari (Tell Hariri) and Tigunani,[39] Arip-Kušuḫ ("Kušuḫ gave"), known from the former of these sites,[40] and Ḫazip-Kušuḫ ("Kušuḫ heard"), with a wide distribution, including attestations from Mari, Chagar Bazar, Shekhna/Shubat-Enlil (Tell Leilan), and Tigunani.[41] Names with Umbu as a theophoric element are known too, examples include Mut-Umpi from Mari and Arip-Umpi from Nuzi.[21]

According to Gernot Wilhelm, there is no indication that Kušuḫ was particularly strongly associated with any specific city.[9] A double temple dedicated to him and Teššub existed in Šuriniwe in the eastern Hurrian kingdom of Arrapha.[3] He was one of the principal deities in the state pantheon of Mitanni as well,[42] and in the treaty between Šuppiluliuma I and Šattiwaza appears right behind Teššub, the head of the pantheon.[24] In offering lists from western Hurrian centers, he appears as a member of the circle of deities (kaluti) of the same god.[43]

Ugaritic reception

The worship of Kušuḫ is well attested in Hurrian documents from Ugarit.[4] In offering lists, he appears between Kumarbi and Iya (Hayya).[33] Once he instead occurs between the latter deity and Dadmiš.[44] A single ritual text indicates that he could be worshiped side by side with local moon god Yarikh, which is one of the examples of the well attested phenomenon involving combining Ugaritic and Hurrian elements in the religious practice of this city.[34] Kušuḫ is also attested in theophoric names from Ugarit, with a total of six individuals bearing them presently known, though one of them was apparently not an inhabitant of the city.[45] The name Eḫli-Kušuḫ occurs the most commonly.[46]

Hittite reception

Kušuḫ was incorporated into the Hittite pantheon alongside other Hurrian deities.[4] He is among the members of the Hurrian pantheon depicted in the Yazılıkaya sanctuary, where he is placed between Šauška's handmaidens Ninatta and Kulitta and the sun god Šimige in the procession of deities following Teššub.[47] Hurrian deities, such as Kušuḫ, commonly appear in theophoric names of rulers in areas under Hittite influence.[48] For example, Hittite prince Piyaššili after being appointed the king of Carchemish by his father Šuppiluliuma I took the regnal name Šarri-Kušuḫ,[49] "Kušuḫ is (my) king."[46]

The name Umbu is attested in Hurro-Hittite context too: examples include oath formulas, where he paired with Šarruma, and texts pertaining the išuwa festival.[21] As a pair, Umbu and Nikkal appear in the entourage of Ḫepat in offering lists.[21]

Mythology

While Kušuḫ does appear in Hurrian myths, according to Gernot Wilhelm they do not provide much information about his individual character.[9] In a cycle of myths focused on the conflict between Kumarbi and Teššub, the so-called Kumarbi Cycle, he belongs to the group of allies of the weather god.[50] He is mentioned in the Song of Silver,[51] presumed to be a part of the aforementioned cycle.[52] The eponymous antagonist, Silver, a son of Kumarbi and a mortal woman,[53] who seemingly temporarily becomes the ruler of the god, at one point brings Kušuḫ and the sun god Šimige down from heaven, and apparently intends to kill them.[54] They bow down to him and ask to be released, arguing that otherwise Silver will have to rule in complete darkness.[54] The conclusion of the composition is not preserved.[54] Kušuḫ is also mentioned briefly in another myth dealing with the same conflict, the Song of Ullikummi, where Kumarbi states that he has to hide the eponymous stone monster somewhere where the allies of, including the moon god, will not be able to find him while he continues to grow.[55] Additionally, he plays a role in the tale of Kešši (CTH 361).[56]

It is sometimes assumed that the Ugaritic myth about the marriage of the local moon god Yarikh and Nikkal (KTU 1.24) had Hurrian origin,[57][58] and according to Nicolas Wyatt it is possible that in a hitherto unknown earlier version the protagonist was Kušuḫ instead.[59] Researchers do not agree if the Ugaritic text was a direct translation, as assumed for example by Aicha Rahmouni,[60] an adaptation of motifs from Hurrian mythology,[61] and also if the proposed Hurrian version was in turn based on an unknown Mesopotamian myth, or if the Ugaritic text was additionally independently influenced by Mesopotamian tradition.[62]

References

- ^ أ ب ت ث Taracha 2009, p. 110.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر Schwemer 2022, p. 374.

- ^ أ ب Haas 2015, p. 545.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Haas 2015, p. 374.

- ^ أ ب Trémouille 2011, p. 102.

- ^ أ ب Schwemer 2008, p. 6.

- ^ أ ب Otten 1983, p. 382.

- ^ Wilhelm 1989, p. VI.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Wilhelm 1989, p. 53.

- ^ Krebernik 1997, p. 364.

- ^ أ ب Válek 2021, pp. 52-53.

- ^ Pardee 2002, p. 281.

- ^ أ ب Trémouille 2000, p. 124.

- ^ Archi 2013, p. 10.

- ^ Beckman 2002, p. 49.

- ^ Trémouille 2000, p. 126.

- ^ Archi 2013, pp. 8-9.

- ^ van den Hout 2021, pp. 115-116.

- ^ Haas 2015, p. 542.

- ^ Haas 2006, p. 198.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Giorgieri 2014, p. 332.

- ^ أ ب Archi 2013, p. 12.

- ^ أ ب ت Giorgieri 2014, p. 333.

- ^ أ ب ت Archi 2013, p. 8.

- ^ Archi 2013, p. 11.

- ^ Taracha 2009, p. 95.

- ^ Haas 2015, p. 635.

- ^ Theuer 2000, p. 19.

- ^ Taracha 2009, p. 124.

- ^ أ ب Wegner 1980, pp. 43-44.

- ^ Dijkstra 2014, p. 76.

- ^ أ ب Haas 2006, p. 208.

- ^ أ ب Schwemer 2001, p. 547.

- ^ أ ب Válek 2021, p. 52.

- ^ Theuer 2000, p. 90.

- ^ Taracha 2009, p. 119.

- ^ Archi 2013, pp. 7-8.

- ^ Trémouille 2000, p. 129.

- ^ Richter 2010, p. 509.

- ^ Richter 2010, p. 510.

- ^ Richter 2010, p. 511.

- ^ Schwemer 2001, p. 461.

- ^ Taracha 2009, p. 118.

- ^ Wegner 1980, p. 193.

- ^ van Soldt 2016, p. 99.

- ^ أ ب Theuer 2000, p. 262.

- ^ Taracha 2009, pp. 94-95.

- ^ Válek 2021, p. 50.

- ^ Wilhelm 1989, p. 36.

- ^ Hoffner 1998, p. 41.

- ^ Haas 2006, p. 150.

- ^ Hoffner 1998, p. 40.

- ^ Hoffner 1998, pp. 48-49.

- ^ أ ب ت Hoffner 1998, p. 50.

- ^ Hoffner 1998, p. 58.

- ^ Bachvarova 2016, p. 184.

- ^ Wiggins 1998, p. 765.

- ^ Rahmouni 2008, p. 335.

- ^ Wyatt 2007, p. 114.

- ^ Rahmouni 2008, p. 341.

- ^ Wiggins 1998, pp. 766-767.

- ^ Wyatt 2007, pp. 114-115.

Bibliography

- Archi, Alfonso (2013). "The West Hurrian Pantheon and Its Background". In Collins, B. J.; Michalowski, P. (eds.). Beyond Hatti: a tribute to Gary Beckman. Atlanta: Lockwood Press. ISBN 978-1-937040-11-6. OCLC 882106763.

- Bachvarova, Mary R. (2016). From Hittite to Homer: the Anatolian background of ancient Greek epic. Cambridge. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139048736. ISBN 978-1-316-39847-0. OCLC 958455749.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Beckman, Gary (2002). "The Pantheon of Emar". Silva Anatolica: Anatolian studies presented to Maciej Popko on the occasion of his 65th birthday. Warsaw: Agade. hdl:2027.42/77414. ISBN 83-87111-12-0. OCLC 51004996.

- Dijkstra, Meindert (2014). "The Hurritic Myth about Sausga of Nineveh and Hasarri (CTH 776.2)". Ugarit-Forschungen. Band 45. Münster: Ugarit Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86835-086-9. OCLC 1101929531.

- Giorgieri, Mauro (2014) (in de)

- Haas, Volkert (2006). Die hethitische Literatur. Walter de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110193794. ISBN 978-3-11-018877-6.

- Haas, Volkert (2015) [1994]. Geschichte der hethitischen Religion. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 1: The Near and Middle East (in الألمانية). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-29394-6. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- Hoffner, Harry (1998). Hittite myths. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press. ISBN 0-7885-0488-6. OCLC 39455874.

- Krebernik, Manfred (1997) (in de)

- Otten, Heinrich (1983) (in de)

- Pardee, Dennis (2002). Ritual and cult at Ugarit. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-90-04-12657-2. OCLC 558437302.

- Rahmouni, Aicha (2008). Divine epithets in the Ugaritic alphabetic texts. Leiden Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-474-2300-3. OCLC 304341764.

- Richter, Thomas (2010). "Ein Hurriter wird geboren... und benannt". In Becker, Jörg; Hempelmann, Ralph; Rehm, Ellen (eds.). Kulturlandschaft Syrien: Zentrum und Peripherie. Festschrift für Jan-Waalke Meyer (in الألمانية). Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86835-034-0. OCLC 587015618.

- Schwemer, Daniel (2001). Die Wettergottgestalten Mesopotamiens und Nordsyriens im Zeitalter der Keilschriftkulturen: Materialien und Studien nach den schriftlichen Quellen (in الألمانية). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-04456-1. OCLC 48145544.

- Schwemer, Daniel (2008). "The Storm-Gods of the Ancient Near East: Summary, Synthesis, Recent Studies: Part II". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. Brill. 8 (1): 1–44. doi:10.1163/156921208786182428. ISSN 1569-2116.

- Schwemer, Daniel (2022). "Religion and Power". Handbook of Hittite Empire. De Gruyter. pp. 355–418. doi:10.1515/9783110661781-009. ISBN 9783110661781.

- Taracha, Piotr (2009). Religions of Second Millennium Anatolia. Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3447058858.

- Theuer, Gabriele (2000). "Der Mondgott in den Religionen Syrien-Palästinas: Unter besonderer Berücksichtigung von KTU 1.24". Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. 173. doi:10.5167/uzh-150559. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- Trémouille, Marie-Claude (2000). "La religione dei Hurriti". La parola del passato: Rivista di studi antichi (in الإيطالية). Napoli: Gaetano Macchiaroli editore. 55. ISSN 2610-8739.

- Trémouille, Marie-Claude (2011) (in fr)

- Válek, František (2021). "Foreigners and Religion at Ugarit". Studia Orientalia Electronica. 9 (2): 47–66. doi:10.23993/store.88230. ISSN 2323-5209.

- van den Hout, Theo (2021). A History of Hittite Literacy: Writing and Reading in Late Bronze-Age Anatolia (1650–1200 BC). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-49488-5. Retrieved 2022-07-30.

- van Soldt, Wilfred H. (2016). "Divinities in Personal Names at Ugarit, Ras Shamra". Etudes ougaritiques IV. Paris Leuven Walpole MA: Editions recherche sur les civilisations, Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-3439-9. OCLC 51010262.

- Wegner, Ilse (1980). Gestalt und Kult der Ištar-Šawuška in Kleinasien (in الألمانية). Kevelaer Neukirchen-Vluyn: Butzon und Bercker Neukirchener Verlag. ISBN 3-7666-9106-6. OCLC 7807272.

- Wiggins, Steve A. (1998). "What's in a name? Yarih at Ugarit". Ugarit-Forschungen (30): 761–780. ISSN 0342-2356. Retrieved 2022-07-29.

- Wilhelm, Gernot (1989). The Hurrians. Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips. ISBN 978-0-85668-442-5. OCLC 21036268.

- Wyatt, Nick (2007). Word of tree and whisper of stone: and other papers on Ugaritian thought. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-716-2. OCLC 171554196.