قمل الرأس

| قمل الرأس Head louse | |

|---|---|

| |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| أصنوفة غير معروفة (أصلحها): | Pediculus |

| Subgenus: | |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | Template:Taxonomy/PediculusP. h. capitis

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Pediculus humanus capitis دو گير، 1767

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Pediculus capitis (De Geer, 1767) | |

قمل الرأس (Pediculus humanus capitis ) هو طفيلي خارجي مقتصر على الإنسان الذي يسبب إصابة قمل الرأس (التهابات بسبب القمل).[1]

قمل الرأس عبارة عن حشرة بلا جناحات يقضي حياته كلها على فروة رأس الإنسان ويتغذى حصريًا على الدم البشري.[1] البشر هم فقط المضيفون لهذا الطفيل المحدد ، في حين أن الشمبانزي يستضيف نوعًا وثيق الصلة ، "Pediculus schaeffi". الأنواع الأخرى من القمل تصيب معظم فصائل الثدييات وجميع فصائل الطيور,[1] وكذلك أجزاء أخرى من جسم الإنسان.

يختلف القمل عن الطفيليات الخارجية الدموية مثل البراغيث في قضاء دورة حياتها بأكملها على مضيف.[2] لا يمكن لقمل الرأس أن يطير ، وأرجلها القصيرة المتكتلة تجعلها غير قادرة على القفز ، أو حتى المشي بكفاءة على الأسطح المستوية.[2]

يختلف قمل الرأس غير الحامل للأمراض عن الحامل المرتبط بالمرض قمل الجسم ("Pediculus humanus humanus") في تفضيل ربط البيض بشعر فروة الرأس بدلاً من الملابس. كلا النوعين من الأنواع الفرعية متطابقان تقريبًا ، ولكنهما لا يتزاوجان عادةً ، على الرغم من أنهما سيفعلان ذلك في ظروف المختبر. من الدراسات الجينية ، يعتقد أنها اختلفت كأنواع فرعية منذ حوالي 30،000 - 110،000 سنة ، عندما بدأ العديد من البشر في ارتداء كمية كبيرة من الملابس.[3][4] وهناك أنواع أخرى بعيدة الصلة من قمل الشعر المتشبث ، العانة أو قمل السرطان ("Pthirus pubis")، و التي تصيب البشر أيضًا. وهو يختلف شكلياً عن النوعين الآخرين وهو أقرب كثيرًا في المظهر إلى القمل الذي يصيب الرئيسيات الأخرى.[5] يُعرف إصابة القمل في أي جزء من الجسم باسم التقمل.[6]

قمل الرأس (خاصة عند الأطفال) كان ولا يزال يخضع لحملات استئصال مختلفة. على عكس قمل الجسم ، فإن قمل الرأس ليس ناقلاً لأي أمراض معروفة. باستثناء حالات العدوى الثانوية النادرة التي تنتج عن خدش اللدغات ، فإن قمل الرأس غير ضار ، وقد اعتبرها البعض مشكلة تجميلية وليست مشكلة طبية. قد يكون تفشي قمل الرأس مفيدًا في المساعدة على تعزيز الاستجابة المناعية الطبيعية ضد القمل التي تساعد البشر في الحماية ضد القمل الجسدي الأكثر خطورة ، والذي يمكنه نقل الأمراض الخطيرة.[7]

الأعراض

قد لا تكون على دراية بعدوى القمل. ومع ذلك، قد تتضمن العلامات والأعراض الشائعة ما يلي:

- الحكة. تعتبر الحكة في فروة الرأس والرقبة والأذنين أكثر الأعراض شيوعًا. يعتبر ذلك رد فعل تحسسيًا للعاب القمل. عندما يصاب الشخص بالعدوى لأول مرة، قد لا تحدث الحكة لمدة من أسبوعين إلى ستة أسابيع بعد العدوى.

- القمل في فروة الرأس. قد يكون القمل واضحًا ولكن من الصعب التقاطه نظرًا لصغره وتجنبه للضوء وسرعة حركته.

- بيض القمل (الصئبان) على خصل الشعر. تلتصق الصئبان بخصل الشعر. قد يكون من الصعب رؤية الصئبان المفرِّخة نظرًا لصغر حجمها الشديد. من الأسهل ملاحظتها حول الأذنين وعلى طول خط الشعر عند الرقبة. قد يكون من الأسهل التقاط الصئبان الفارغة لأنها أفتح في اللون وأبعد عن فروة الرأس. ومع ذلك، لا يشير وجود الصئبان بالضرورة إلى العدوى النشطة.

الشك في العدوى

تشمل الأمور التي يتم الخلط بينها وبين الصئبان في كثير من الأحيان:

- الصئبان الفارغة أو الميتة من العدوى السابقة بقمل الرأس

القشرة

- بقايا منتجات الشعر

- جزءًا من نسيج الشعر الميت على خصل الشعر (أسطوانة الشعرة)

- الأنسجة القشرية أو الأتربة أو الفضلات الأخرى

- الحشرات الصغيرة الأخرى الموجودة في الشعر

شكل القملة

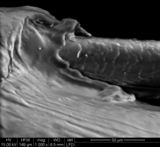

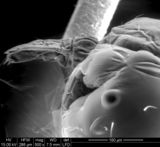

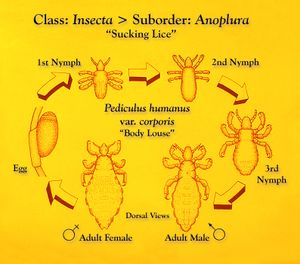

Like other insects of the suborder Anoplura, adult head lice are small (2.5–3 mm long), dorsoventrally flattened (see anatomical terms of location), and entirely wingless.[8] The thoracic segments are fused, but otherwise distinct from the head and abdomen, the latter being composed of seven visible segments.[9] Head lice are grey in general, but their precise color varies according to the environment in which they were raised.[9] After feeding, consumed blood causes the louse body to take on a reddish color.[9]

الرأس

One pair of antennae, each with five segments, protrudes from the insect's head. Head lice also have one pair of eyes. Eyes are present in all species within the Pediculidae (the family of which the head louse is a member), but are reduced or absent in most other members of the Anoplura suborder.[8] Like other members of the Anoplura, head lice mouth parts are highly adapted for piercing skin and sucking blood.[8] These mouth parts are retracted into the insect's head except during feeding.[9][10]

الجذع

Six legs project from the fused segments of the thorax.[9] As is typical in the Anoplura, these legs are short and terminate with a single claw and opposing "thumb".[9] Between its claw and thumb, the louse grasps the hair of its host.[9] With their short legs and large claws, lice are well adapted to clinging to the hair of their host. These adaptations leave them incapable of jumping, or even walking efficiently on flat surfaces. Lice can climb up strands of hair very quickly, allowing them to move quickly and reach another host.[2]

البطن

Seven segments of the louse abdomen are visible.[9] The first six segments each have a pair of spiracles through which the insect breathes.[9] The last segment contains the anus and (separately) the genitalia.[9]

الفروق بين الجنسين

In male lice, the front two legs are slightly larger than the other four. This specialized pair of legs is used for holding the female during copulation. Males are slightly smaller than females and are characterized by a pointed end of the abdomen and a well-developed genital apparatus visible inside the abdomen. Females are characterized by two gonopods in the shape of a W at the end of their abdomens.

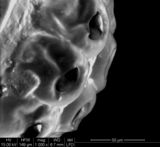

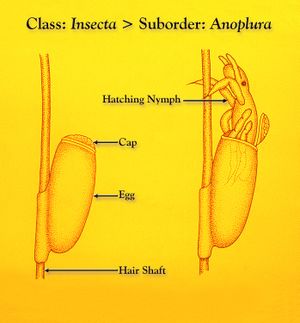

البويضات/الصئبان

Like most insects, head lice are oviparous. Females lay about three or four eggs per day. Louse eggs or nits, are attached near the base of a host hair shaft.[11][12] Egg-laying behavior is temperature dependent and likely seeks to place the egg in a location that will be conducive to proper embyro development (which is, in turn, temperature dependent). In cool climates, eggs are generally laid within 3–5 mm of the scalp surface.[11][12] In warm climates, and especially the tropics, eggs may be laid 6 بوصات (15 cm) or more down the hair shaft.[13]

To attach an egg, the adult female secretes a glue from her reproductive organ. This glue quickly hardens into a "nit sheath" that covers the hair shaft and large parts of the egg except for the operculum, a cap through which the embryo breathes.[12] The glue was previously thought to be chitin-based, but more recent studies have shown it to be made of proteins similar to hair keratin.[12]

Each egg is oval-shaped and about 0.8 mm in length.[12] They are bright, transparent, and tan to coffee-colored so long as they contain an embryo, but appear white after hatching.[12][13] Head lice hatch typically six to nine days after oviposition.[11][14]

After hatching, the louse nymph leaves behind its egg shell (usually known as a "nit", see below), still attached to the hair shaft. The empty egg shell remains in place until physically removed by abrasion or the host, or until it slowly disintegrates, which may take 6 or more months.[14]

The term nit refers to a louse egg or young louse.[15] With respect to eggs, this rather broad definition includes the following:[16] Accordingly, on the head of an infested individual, these eggs could be found:

- Viable eggs that will eventually hatch

- Remnants of already-hatched eggs (nits)

- Nonviable eggs (dead embryo) that will never hatch

This has produced some confusion in, for example, school policy (see The "no-nit" policy) because, of the three items listed above, only eggs containing viable embryos have the potential to infest or reinfest a host.[17] Some authors have reacted to this confusion by restricting the definition of nit to describe only a hatched or nonviable egg:

In many languages, the terms used for the hatched eggs, which were obvious for all to see, have subsequently become applied to the embryonated eggs that are difficult to detect. Thus, the term "nit" in English is often used for both. However, in recent years, my colleagues and I have felt the need for some simple means of distinguishing between the two without laborious qualification. We have, therefore, come to reserve the term "nit" for the hatched and empty egg shell and refer to the developing embryonated egg as an "egg".

— Ian F. Burgess (1995)[14]

The empty eggshell, termed a nit...

— J. W. Maunder (1983)[2]

...nits (dead eggs or empty egg cases)...

— Kosta Y. Mumcuoglu and others (2006)[18]

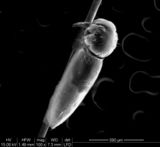

التطور واليرقات

التكاثر ودورة الحياة

تفقس بيضة القملة بعد ثمانية أو تسعة أيام. وما ينشأ هو شكل غير ناضج للقمل يُدعى باسم حوراء. تصبح الحوراء قملة بالغة ناضجة بعد تسعة إلى 12 يومًا وتعيش البالغة لمدة ثلاثة إلى أربعة أسابيع.[19]

Adult head lice reproduce sexually, and copulation is necessary for the female to produce fertile eggs. Parthenogenesis, the production of viable offspring by virgin females, does not occur in Pediculus humanus.[1] Pairing can begin within the first 10 hours of adult life.[1] After 24 hours, adult lice copulate frequently, with mating occurring during any period of the night or day.[1][20] Mating attachment frequently lasts more than an hour.[20] Young males can successfully pair with older females, and vice versa.[1]

Experiments with P. h. humanus (body lice) emphasize the attendant hazards of lice copulation. A single young female confined with six or more males will die in a few days, having laid very few eggs.[1] Similarly, death of a virgin female was reported after admitting a male to her confinement.[20] The female laid only one egg after mating, and her entire body was tinged with red—a condition attributed to rupture of the alimentary canal during the sexual act.[20] Old females frequently die following, if not during, intercourse.[20]

A single louse has a 30-day lifecycle beginning from the moment the nit is laid until the adult louse dies.[21]

Factors affecting infestation

The number of children per family, the sharing of beds and closets, hair washing habits, local customs and social contacts, healthcare in a particular area (e.g. school), and socioeconomic status were found to be significant factors in head louse infestation. Girls are two to four times more frequently infested than boys. Children between 4 and 14 years of age are the most frequently infested group.[21]

Behaviour

Feeding

All stages except eggs are blood-feeders and bite the skin four to five times daily to feed. They inject saliva which contains an anticoagulant and suck blood. The digested blood is excreted as dark red frass.[22]

Position on host

Although any part of the scalp may be colonized, lice favor the nape of the neck and the area behind the ears, where the eggs are usually laid. Head lice are repelled by light and move towards shadows or dark-coloured objects in their vicinity.[20][23]

Transmission

Lice have no wings or powerful legs for jumping, so they move using their claw-like legs to transfer from hair to hair.[22] Normally, head lice infest a new host only by close contact between individuals, making social contacts among children and parent-child interactions more likely routes of infestation than shared combs, hats, brushes, towels, clothing, beds, or closets. Head-to-head contact is by far the most common route of lice transmission.[24]

Distribution

About 6–12 million people, mainly children, are treated annually for head lice in the United States alone. In the UK, it is estimated that two thirds of children will experience at least one case of head lice before leaving primary school.[25] High levels of louse infestations have also been reported from all over the world, including Australia, Denmark, France, Ireland, Israel, and Sweden.[17][26] Head lice can survive off the head, for example on soft furnishings such as pillow cases, on hairbrushes, or on coat hoods for up to 48 hours.

Archaeogenetics

Analysis of the DNA of lice found on Peruvian mummies may indicate that some diseases (such as typhus) may have passed from the New World to the Old World, instead of the other way around.[27]

Genome

The sequencing of the genome of the body louse was first proposed in the mid-2000s[28] and the annotated genome was published in 2010.[29] An analysis of the body and head louse transcriptomes revealed these two organisms are extremely similar genetically.[30]

Mitochondrial clades

Human lice are divided into three deeply divergent mitochondrial clades known as A, B, and C.[31][32] Two subclades have been identified, D (a sister clade of A) and E (a sister clade of C).[33][34]

Clade A

- head and body: worldwide

- found in ancient Roman Judea

Clade D (sister of clade A)

- head and body: Central Africa, Ethiopia, United States

Clade B

- head only: worldwide

- found in ancient Roman Judea and 4,000-year-old Chilean mummy

Clade C

- head only: Ethiopia, Nepal, Thailand

Clade E (sister of clade C)

- head only: West Africa

الانتقال

يزحف قمل الرأس ولكنه لا يستطيع القفز أو الطيران. وغالبًا ما يحدث انتقال قملة رأس من شخص إلى آخر عن طريق التلامس المباشر. ولذلك يحدث الانتقال في كثير من الأحيان داخل أفراد العائلة أو بين الأطفال الذين يتلامسون عن قرب في المدرسة أو في أثناء اللعب.

لا يرجَّح حدوث الانتقال غير المباشر، ولكن قد ينتقل القمل من شخص إلى آخر عن طريق العناصر مثل التالي:

- القبعات والأوشحة

- الفرش والأمشاط

- إكسسوارات الشعر

- السماعات

- الوسائد

- المفروشات

- المناشف

يمكن أيضًا أن يحدث الانتقال غير المباشر ضمن الملابس التي يتم تخزينها معًا. على سبيل المثال، يمكن أن تعمل القبعات أو الأوشحة المعلقين على نفس الخطاف أو مخزنين في نفس خزانة المدرسة كوسائل انتقال القمل.

لا تلعب الحيوانات الأليفة المنزلية مثل الكلاب والقطط دورًا في انتشار قمل الرأس.

عوامل الخطر

ولأن قمل الرأس ينتشر بشكل أساسي عن طريق احتكاك الرأس بالرأس، فيكون خطر الانتقال أكبر بين صغار السن الذين يلعبون أو يذهبون إلى المدرسة معًا. في الولايات المتحدة، تحدث حالات قمل الرأس في معظم الأحيان في الأطفال في مرحلة ما قبل المدرسة حتى المدارس المتوسطة.

المضاعفات

إذا كان الطفل يقوم بحك جزء من فروة الرأس مصاب بالقمل، فمن المحتمل أن تقع خدوش بالجلد وتتطور إلى التهاب.

الوقاية

من الصعب منع انتشار قمل الرأس بين الأطفال في مرافق رعاية الأطفال والمدارس حيث يوجد الكثير من الاتصالات القريبة. وتُعد فرصة الانتقال غير المباشر من الأغراض الشخصية طفيفة.

ومع ذلك، يُعد تعليق الأطفال لملابسهم على شماعة منفصلة عن ملابس الأطفال الآخرين، وعدم مشاركة الأمشاط، والفرش، والقبعات والأوشحة ممارسة جيدة عامةً. لا يُعد القلق من انتقال قمل الرأس سببًا جيدًا لتجنب مشاركة أغطية الرأس الواقية للرياضة والدراجات عندما تكون المشاركة ضرورية.

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Buxton, Patrick A. (1947). "The biology of Pediculus humanus". The Louse; an account of the lice which infest man, their medical importance and control (2nd ed.). London: Edward Arnold. pp. 24–72.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Maunder, JW (1983). "The Appreciation of Lice". Proceedings of the Royal Institution of Great Britain. 55: 1–31.

- ^ Kittler R, Kayser M, Stoneking M (August 2003). "Molecular evolution of Pediculus humanus and the origin of clothing". Current Biology. 13 (16): 1414–7. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00507-4. PMID 12932325.

- ^ Stoneking, Mark (29 December 2004). "Erratum: Molecular Evolution of Pediculus humanus and the Origin of Clothing". Current Biology. 14 (24): 2309. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.024.

- ^ Buxton, Patrick A. (1947). "The crab louse Phthirus pubis". The Louse; an account of the lice which infest man, their medical importance and control (2nd ed.). London: Edward Arnold. pp. 136–141.

- ^ "pediculosis – Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ Rozsa, L; Apari, P. (2012). "Why infest the loved ones – inherent human behaviour indicates former mutualism with head lice" (PDF). Parasitology. 139 (6): 696–700. doi:10.1017/s0031182012000017. PMID 22309598.

- ^ أ ب ت Buxton, Patrick A. (1947). "The Anoplura or Sucking Lice". The Louse; an account of the lice which infest man, their medical importance and control (2nd ed.). London: Edward Arnold. pp. 1–4.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر Buxton, Patrick A. (1947). "The Anatomy of Pediculus humanus". The Louse; an account of the lice which infest man, their medical importance and control (2nd ed.). London: Edward Arnold. pp. 5–23.

- ^ "Lice (Pediculosis)". The Merck Veterinary Manual. Whitehouse Station, NJ USA: Merck & Co. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ أ ب ت Williams LK, Reichert A, MacKenzie WR, Hightower AW, Blake PA (May 2001). "Lice, nits, and school policy". Pediatrics. 107 (5): 1011–5. doi:10.1542/peds.107.5.1011. PMID 11331679.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG (July 2005). "Head lice: scientific assessment of the nit sheath with clinical ramifications and therapeutic options". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 53 (1): 129–33. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.01.134. PMID 15965432.

- ^ أ ب Meinking, Terri Lynn (May–June 1999). "Infestations". Current Problems in Dermatology. 11 (3): 75–118. doi:10.1016/S1040-0486(99)90005-4.

- ^ أ ب ت Burgess, IF (1995). "Human lice and their management". Advances in Parasitology Volume 36. Advances in Parasitology. Vol. 36. pp. 271–342. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(08)60493-5. ISBN 978-0-12-031736-3. PMID 7484466.

- ^ "nit – Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". Retrieved 2018-12-28.

- ^ Pollack RJ, Kiszewski AE, Spielman A (August 2000). "Overdiagnosis and consequent mismanagement of head louse infestations in North America". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 19 (8): 689–93, discussion 694. doi:10.1097/00006454-200008000-00003. PMID 10959734.

- ^ أ ب Burgess, IF (2004). "Human lice and their control". Annu. Rev. Entomol. 49: 457–81. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123253. PMID 14651472.

- ^ Mumcuoglu KY, Meinking TA, Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG (August 2006). "Head louse infestations: the 'no nit' policy and its consequences". International Journal of Dermatology. 45 (8): 891–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02827.x. PMID 16911370.

- ^ "قمل الرأس". مايو كلينيك. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Bacot A (1917). "Contributions to the bionomics of Pediculus humanus (vestimenti) and Pediculus capitis". Parasitology. 9 (2): 228–258. doi:10.1017/S0031182000006065.

- ^ أ ب Mumcuoglu KY, Miller J, Gofin R, et al. (September 1990). "Epidemiological studies on head lice infestation in Israel. I. Parasitological examination of children". International Journal of Dermatology. 29 (7): 502–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1990.tb04845.x. PMID 2228380.

- ^ أ ب Weems, Jr., H. V.; Fasulo, T. R. (June 2007). "Human Lice: Body Louse, Pediculus humanus humanus Linnaeus and Head Louse, Pediculus humanus capitis De Geer (Insecta: Phthiraptera (=Anoplura): Pediculidae)". University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ^ Nuttall, George H. F. (1919). "The biology of Pediculus humanus, Supplementary notes". Parasitology. 11 (2): 201–221. doi:10.1017/s0031182000004194.

- ^ "NJ Head Lice | Philadelphia and South New Jersey Hair Lice". Lice Lifters New Jersey. Archived from the original on 2013-01-12. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- ^ "Two thirds of British children will catch head lice during school years, study finds". instituteofmums.com (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). 2017-04-20. Retrieved 2017-09-28.

- ^ Mumcuoglu KY, Barker SC, Burgess IE, et al. (April 2007). "International guidelines for effective control of head louse infestations". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 6 (4): 409–14. PMID 17668538.

- ^ Anderson, Andrea (February 8, 2008). "DNA from Peruvian Mummy Lice Reveals History". GenomeWeb Daily News. GenomeWeb LLC. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- ^ Pittendrigh BR, Clark JM, Johnston JS, Lee SH, Romero-Severson J, Dasch GA (November 2006). "Sequencing of a new target genome: the Pediculus humanus humanus (Phthiraptera: Pediculidae) genome project". Journal of Medical Entomology. 43 (6): 1103–11. doi:10.1603/0022-2585(2006)43[1103:SOANTG]2.0.CO;2. PMID 17162941.

- ^ Kirkness EF, Haas BJ, Sun W, et al. (July 2010). "Genome sequences of the human body louse and its primary endosymbiont provide insights into the permanent parasitic lifestyle". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (27): 12168–73. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10712168K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003379107. PMC 2901460. PMID 20566863.

- ^ Olds BP, Coates BS, Steele LD, et al. (April 2012). "Comparison of the transcriptional profiles of head and body lice". Insect Molecular Biology. 21 (2): 257–68. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2583.2012.01132.x. PMID 22404397.

- ^ Morand, Serge; Krasnov, Boris R.; Littlewood, D. Timothy J. (26 February 2015). Parasite Diversity and Diversification: Evolutionary Ecology Meets Phylogenetics. Cambridge University Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-316-23993-3. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Knapp, Michael; Boutellis, Amina; Drali, Rezak; Rivera, Mario A.; Mumcuoglu, Kosta Y.; Raoult, Didier (2013). "Evidence of Sympatry of Clade A and Clade B Head Lice in a Pre-Columbian Chilean Mummy from Camarones". PLoS ONE. 8 (10): e76818. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...876818B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076818. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3813697. PMID 24204678.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Gao, Feng; Amanzougaghene, Nadia; Mumcuoglu, Kosta Y.; Fenollar, Florence; Alfi, Shir; Yesilyurt, Gonca; Raoult, Didier; Mediannikov, Oleg (2016). "High Ancient Genetic Diversity of Human Lice, Pediculus humanus, from Israel Reveals New Insights into the Origin of Clade B Lice". PLOS ONE. 11 (10): e0164659. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1164659A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164659. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5065229. PMID 27741281.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Liao, Chien-Wei; Cheng, Po-Ching; Chuang, Ting-Wu; Chiu, Kuan-Chih; Chiang, I-Chen; Kuo, Juo-Han; Tu, Yun-Hung; Fan, Yu-Min; Jiang, Hai-Tao; Fan, Chia-Kwung (2017). "Prevalence of Pediculus capitis in schoolchildren in Battambang, Cambodia". Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 52 (4): 585–591. doi:10.1016/j.jmii.2017.09.003. ISSN 1684-1182. PMID 29150362.