الطيور الوركية

| Ornithischians | |

|---|---|

| |

| مجموعة من هياكل أحفورات طيور وركية. مع عقارب الساعة من أعلى اليسار: Heterodontosaurus tucki (a heterodontosaurid), Stegosaurus stenops (ستگوصور مصفح)، Euoplocephalus tutus (ankylosaur مدرع)، Edmontosaurus annectens (هادروصور بطي المنقار)، Stegoceras validum (pachycephalosaur غليظ الرأس)، و Triceratops horridus (ceratopsian ذو قرون). | |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| أصنوفة غير معروفة (أصلحها): | Crocopoda |

| الفرع الحيوي: | الديناصورات |

| الرتبة: | †الطيور الوركية Seeley, 1888 |

| المجموعات الفرعية | |

| Synonyms | |

الطيور الوركية (Ornithischia ؛ /ɔːrnɪˈθɪskiə/) هي فرع منقرض من ديناصورات أغلبها عاشب تتميز ببنية حوضية مشابهة لتلك في الطيور.[2] الاسم الطيور الوركية Ornithischia، أو "طيرية الورك"، تعكس هذا التشابه ومشتقة من الجذع اليوناني ornith- (ὀρνιθ-)، ويعني "طيري" (صفة)، و ischion (ἴσχιον)، وجمعها ischia، تعني "مفصل المقعدة". إلا أن الطيور تتصل عن بعد بهذه المجموعة، إذ أن الطيور هي ديناصورات وحوش قدمية.[2]

الطيور الوركية ذات التحورات التشريحية المعروفة جيداً تضم ceratopsians أو الديناصورات "مقرَّنة الوجه" (مثل ترايسراتوپس)، الديناصورات المدرعة (حملة الدروع) مثل الستگوصورات و ankylosaurs, pachycephalosaurids and the ornithopods.[2] وهناك دليل قوي على أن بعض مجموعات الطيور الوركية عاشت في قطعان،[2][3] وكثيراً ما كانت منفصلة حسب المجموعة العمرية، فيشكل الأحداث أسرابهم منفصلين عن البالغين.[4] وبعضهم كان مغطى ولو جزئياً بأحزمة فتيلية (مثل الشعر أو الريش)، وثمة جدال كبير حول ما إذا كانت تلك الفتائل التي عُثِر عليها في عينات Tianyulong[5] وPsittacosaurus،[6] و Kulindadromeus قد كانت ريشاً بدائياً.[7]

وحالياً، فإن التحديد الدقيق لمكان الطيور الوركية ضمن شجرة الديناصورات هو أمر شائك.[8] فتقليدياً، تُعتبر المجموعة شقيقة لسحليات الورك (التي تضم الوحوش القدمية و أشباه سحليات الأقدام).[9] وفي فرضية تطورية بديلة للديناصورات، اقترحها بارون ونورمان وبارِت في دورية نيتشر في 2017، فإن الطيور الوركية وكذلك الوحوش القدمية جـُمـِّعا معاً في الفرع Ornithoscelida.[10][11] عمل بارون ورفاقه برز له تحدي من كونسورتيوم دولي لخبراء الديناصورات المبكرة بقيادة ماكس لانگر. إلا أن البيانات الداعمة للتموضع الأكثر تقليدية للطيور الوركية، كأصنوفة شقيقة لسحليات الورك، وُجـِد أنها غير ذات حيثيية إحصائية بالمقارنة بالأدلة الداعمة لفرضية Ornithoscelida، في كلٍ من دراسة لانگر ورفاقة وفي الرد على تلك الدراسة من بارون ورفاقه.[12][13] وثمة دراسة اضافية في 2017 لاقت بعض الدعم لنموذج Phytodinosauria المهجور سابقاً، الذي بوَّب الطيور الوركية مع أشباه سحليات الأقدام.[14]

الوصف

في 1887، قسَّم هاري سيلي شجرة الديناصورات إلى فرعين: طيور وركية وسحليات الأقدام. الطيور الوركية هي فرع مدعوم بقوة من أدلة وفيرة من السمات التشخيصية (السمات المشتركة).[2] السمتان الأبرز هما مفصل مقعدة "مثل الطيور" و بنية أسنان مثل المنقار، بالرغم من أنهما تشاركا في سمات أخرى كذلك.[2]

"وِرك"

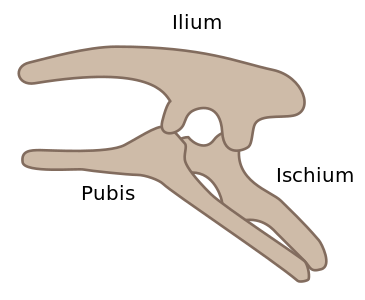

The ornithischian pelvis is "opisthopubic", meaning that the pubis points down and back (posterior) parallel with the ischium (Figure 1a).[2] Additionally, the pelvis has a forward-pointing process to support the abdomen.[2] This results in a four-pronged pelvic structure. In contrast to this, the saurischian pelvis is "propubic", meaning the pubis points toward the head (anterior), as in ancestral reptiles (Figure 1b).[2]

The opisthopubic pelvis independently evolved at least three times in dinosaurs (in ornithischians, birds and therizinosauroids).[15] Some argue that the opisthopubic pelvis evolved a fourth time in the clade Dromaeosauridae, but this is controversial, as other authors argue that dromeosaurids are mesopubic.[15]

Predentary

Ornithischians share a unique bone called the predentary (Figure 2).[2] This unpaired bone is found at the front of the lower jaws and presumably aided ornithischians in cropping vegetation. In 2017 Baron & Barrett suggested that Chilesaurus may represent an early diverging ornithischian that had not yet acquired the predentary of all other ornithischians.[16][17]

Figure 1a - Ornithischian propisthopubic pelvic structure (left side)

سمات أخرى

- Ornithischians had paired premaxillary bones that were toothless and roughened at the tip of the snout (presumably due to the attachment of a keratinous beak).[2]

- Ornithischians developed a narrow "eyebrow", or palpebral bone, across the outside of the eye socket.[2]

- Ornithischians had reduced, or even closed-off, antorbital fenestrae (the fenestra in front of the eye socket).[2]

- Ornithischian jaw joints were lowered below the level of the teeth, bringing the teeth into simultaneous occlusion.[2]

- Ornithischians had "leaf-shaped" cheek teeth.[2]

- Ornithischian backbones were stiffened near the pelvis by the ossification of tendons above the sacrum. Additionally, ornithischians had at least five sacral vertebrae attaching to the pelvis.[2]

التبويب

Ornithischia is a branch-based taxon defined as all dinosaurs more closely related to Triceratops horridus Marsh, 1889 than to either Passer domesticus (Linnaeus, 1758) or Saltasaurus loricatus Bonaparte & Powell, 1980.[18] Genasauria comprises the clades Thyreophora and Neornithischia. Thyreophora includes Stegosauria (like the armored Stegosaurus) and Ankylosauria (like Ankylosaurus). Neornithischia comprises several basal taxa, Marginocephalia (Ceratopsia and Pachycephalosauria), and Ornithopoda (including duck-bills (hadrosaurs), such as Edmontosaurus). Cerapoda is a relatively recent concept (Sereno, 1986).

The cladogram below follows a 2009 analysis by Zheng and colleagues. All tested members of Heterodontosauridae form a polytomy.[19]

| Ornithischia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cladogram after Butler et al., 2011. Ornithopoda includes Hypsilophodon, Jeholosaurus and others.[5]

| Ornithischia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

علم البيئة العتيق

Ornithischians shifted from bipedal to quadrupedal posture at least three times in their evolutionary history and it has been shown primitive members may have been capable of both forms of movement.[20]

Most ornithischians were herbivorous.[2] In fact, most of the unifying characters of Ornithischia are thought to be related to this herbivory.[2] For example, the shift to an opisthopubic pelvis is thought to be related to the development of a large stomach or stomachs and gut which would allow ornithischians to digest plant matter better.[2] The smallest known Ornithischians are Fruitadens haagarorum.[21] The largest Fruitadens individuals reached just 65–75 cm. Previously, only carnivorous, saurischian theropods were known to reach such small sizes.[21] At the other end of the spectrum, the largest known ornithischians reach about 15 meters (smaller than the largest saurischians).[22]

However, not all ornithischians were strictly herbivorous. Some groups, like the heterodontosaurids, were likely omnivores.[23] At least one species of ankylosaurian, Liaoningosaurus paradoxus, appears to have been at least partially carnivorous, with hooked claws, fork-like teeth, and stomach contents suggesting that it may have fed on fish.[24]

There is strong evidence that some ornithischians lived in herds.[2][3] This evidence consists of multiple bones beds with large numbers of the same species in different age classes who died simultaneously.[2][3]

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ Ferigolo, J.; Langer, M. C. (2007). "A Late Triassic dinosauriform from south Brazil and the origin of the ornithischian predentary bone". Historical Biology. 19: 23–33. doi:10.1080/08912960600845767.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف ق Fastovsky, David E.; Weishampel, David B. (2012). Dinosaurs: A Concise Natural History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1107276462.

- ^ أ ب ت Qi, Zhao; Barrett, Paul M.; Eberth, David A. (2007-09-01). "Social Behaviour and Mass Mortality in the Basal Ceratopsian Dinosaur Psittacosaurus (الطباشيري المبكر، الصين)". Palaeontology (in الإنجليزية). 50 (5): 1023–1029. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00709.x. ISSN 1475-4983.

- ^ Zhao, Q. (2013). "Juvenile-only clusters and behaviour of the Early Cretaceous dinosaur Psittacosaurus". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. doi:10.4202/app.2012.0128.

- ^ أ ب Richard J. Butler, Jin Liyong, Chen Jun, Pascal Godefroit (May 2011). "The postcranial osteology and phylogenetic position of the small ornithischian dinosaur Changchunsaurus parvus from the Quantou Formation (Cretaceous: Aptian–Cenomanian) of Jilin Province, north-eastern China". Palaeontology. 54 (3): 667–683. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01046.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mayr, Gerald; Peters, Stefan D.; Plodowski, Gerhard; Vogel, Olaf (2002-08-01). "Bristle-like integumentary structures at the tail of the horned dinosaur Psittacosaurus". Naturwissenschaften (in الإنجليزية). 89 (8): 361–365. doi:10.1007/s00114-002-0339-6. ISSN 0028-1042. PMID 12435037.

- ^ Godefroit, P.; Sinitsa, S.M.; Dhouailly, D.; Bolotsky, Y.L.; Sizov, A.V.; McNamara, M.E.; Benton, M.J.; Spagna, P. (2014). "A Jurassic ornithischian dinosaur from Siberia with both feathers and scales" (PDF). Science. 345 (6195): 451–455. doi:10.1126/science.1253351.

- ^ Matthew G. Baron (2018). "Pisanosaurus mertii and the Triassic ornithischian crisis: could phylogeny offer a solution?". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. in press. doi:10.1080/08912963.2017.1410705.

- ^ Seeley, H.G. (1888). "On the classification of the fossil animals commonly named Dinosauria". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 43: 165–171. doi:10.1098/rspl.1887.0117.

- ^ Baron, M.G.; Norman, D.B.; Barrett, P.M. (2017). "A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution". Nature. 543: 501–506. doi:10.1038/nature21700.

- ^ https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/new-study-shakes-the-roots-of-the-dinosaur-family-tree

- ^ Max C. Langer; Martín D. Ezcurra; Oliver W. M. Rauhut; Michael J. Benton; Fabien Knoll; Blair W. McPhee; Fernando E. Novas; Diego Pol; Stephen L. Brusatte (2017). "Untangling the dinosaur family tree". Nature. 551 (7678): E1–E3. doi:10.1038/nature24011.

- ^ Matthew G. Baron; David B. Norman; Paul M. Barrett (2017). "Baron et al. reply". Nature. 551 (7678): E4–E5. doi:10.1038/nature24012.

- ^ Luke A. Parry; Matthew G. Baron; Jakob Vinther (2017). "Multiple optimality criteria support Ornithoscelida". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (10): 170833. doi:10.1098/rsos.170833.

- ^ أ ب Currie, Philip J.; Padian, Kevin (1997-10-06). Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs (in الإنجليزية). Academic Press. pp. 537–538. ISBN 9780080494746.

- ^ Baron, Matthew G.; Barrett, Paul M. (2017). "A dinosaur missing-link? Chilesaurus and the early evolution of ornithischian dinosaurs". Biology Letters. The Royal Society. 13 (8). doi:10.1098/rsbl.2017.0220.

- ^ http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/study-identifies-dinosaur-missing-link

- ^ Butler, Richard; Upchurch, Paul; Norman, David (2008). "The phylogeny of ornithischian dinosaurs". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (1): 1–40. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002271.

- ^ Zheng, Xiao-Ting; You, Hai-Lu; Xu, Xing; Dong, Zhi-Ming (19 March 2009). "An Early Cretaceous heterodontosaurid dinosaur with filamentous integumentary structures". Nature. 458 (7236): 333–336. doi:10.1038/nature07856. PMID 19295609.

- ^ Jeffrey A. Wilson; Claudia A. Marsicano; Roger M. H. Smith (6 October 2009). "Dynamic Locomotor Capabilities Revealed by Early Dinosaur Trackmakers from Southern Africa". PLoS ONE. PLOS ONE. 4: e7331. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007331.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ أ ب Butler, Richard J.; Galton, Peter M.; Porro, Laura B.; Chiappe, Luis M.; Henderson, Donald M.; Erickson, Gregory M. (2010-02-07). "Lower limits of ornithischian dinosaur body size inferred from a new Upper Jurassic heterodontosaurid from North America". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences (in الإنجليزية). 277 (1680): 375–381. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1494. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2842649. PMID 19846460.

- ^ Yannan, Ji; Xuri, Wang; Yongqing, Liu; Qiang, Ji (2011-02-01). "Systematics, Behavior and Living Environment of Shantungosaurus Giganteus (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae)". Acta Geologica Sinica - English Edition (in الإنجليزية). 85 (1): 58–65. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2011.00378.x. ISSN 1755-6724.

- ^ Barrett, P. M.; Rayfield, E. J. (2006). "Ecological and evolutionary implications of dinosaur feeding behaviour". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 21 (4): 217–224. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.01.002.

- ^ Ji, Q.; Wu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Ten, F.; Wang, X.; Ji, Y. (2016). "Fish-hunting ankylosaurs (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the Cretaceous of China". Journal of Geology. 40: 2.

- Butler, R.J. (2005). "The 'fabrosaurid' ornithischian dinosaurs of the Upper Elliot Formation (Lower Jurassic) of South Africa and Lesotho". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 145 (2): 175–218. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2005.00182.x.

- Sereno, P.C. (1986). "Phylogeny of the bird-hipped dinosaurs (order Ornithischia)". National Geographic Research. 2 (2): 234–256.

وصلات خارجية

- Ornithischia, from Palæos. (cladogram, characteristics)