شبه بلورة

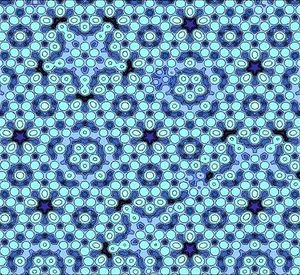

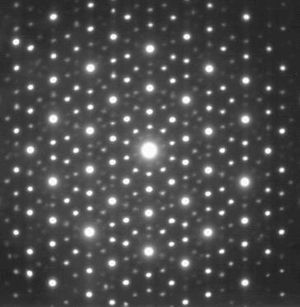

أشباه البلورات Quasicrystals هي أشكال بنيوية مرتبة ولكن غير دورية. ويشكلون أنماطاً تملأ كل الفراغ بالرغم من أنهم يفتقدون التناظر الانتقالي translational symmetry. بينما البلورات، حسب مبرهنة التقييد البلوري الكلاسيكية، يمكن أن يكون لها تماثل دوراني فقط ثنائي وثلاثي ورباعي وسداسي، فإن نمط حيود براگ لأشباه البلورات يُظهر قمماً حادة برتب تناظر أخرى، مثل 5-طيات.

التبليطات غير الدورية اكتشفها الرياضيون في مطلع عقد 1960، وبعد نحو عشرين عاماً وُجِد أنهم ينطبقون على دراسة أشباه البلورات. اكتشاف تلك الأشكال غير الدورية في الطبيعة انتج نقلة نوعية في مجالات علم البلورات. Quasicrystals had been investigated and observed earlier[1] ولكن حتى عقد 1980، كانوا يتم تجاهلهم لصالح وجهات النظر السائدة عن البنية الذرية للمادة.

فتقريباً، فالترتيب يكون غير دوري إذا افتقد النتاظر الانتقالي، ويعني ذلك أن نسخة منقولة لن تتطابق تماماً مع الأصل. التعريف الرياضي الأكثر دقة هو أنه يستحيل وجود تماثل انتقالي في أكثر من n – 1 اتجاه مستقل خطياً، حيث n هي بعد الفراغ المملوء؛ أي أن التبليط ثلاثي الأبعاد الظاهر في شبه البلورة قد يكون له تناظر انتقالي في بعدين. القدرة على الحيود تأتي من وجود عدد كبير، بشكل غير محدود، من العناصر ذات تباعد منتظم، وهي خاصية توصف بتساهل بأنها ترتيب طويل المدى. وتجريبياً، فإن اللادورية تظهر في التناظر غير المعتاد لنمط الحيود، أي التناظر من الرتب غير 2, 3, 4، أو 6. أول حالة مذاعة رسمياً لما صار يُعرَف لاحقاً بأشباه البلورات قام بها دان شكتمان من تخنيون - معهد إسرائيل للتكنولوجيا وزملاؤه في 1984[2]. وقد حصل شكتمان على جائزة نوبل في الكيمياء في 2011 على اكتشافاته.[3] وفي الأصل، فإن الشكل الجديد للمادة من أشباه البلورات سُمي "شكتمانيت Shechtmanite"[4] ولتكريم العالم من تخنيون على اكتشافه - وهو الاكتشاف الذي استغرق سنين ليحصل على الشرعية العلمية[5].

التاريخ

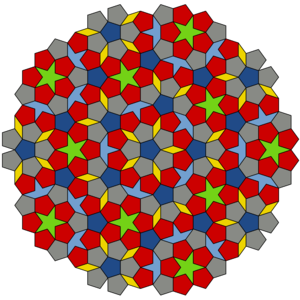

البنى شبه الدورية معروقة قبل القرن العشرين بكثير. فعلى سبيل المثال، البلاطات في مسجد من العصور الوسطى في إصفهان، إيران، مرتبون في نمط شبه بلوري.[6] وفي 1961، سأل هاو وانگ سؤالاً عما إذا كان تحديد أن فئة من البلاطات تسمح بتبليط المستوى هو مشكلة غير قابلة للحل خوارزمياً أم قابلة. He conjectured that it is solvable, relying on the hypothesis that any set of tiles which can tile the plane can do it periodically (hence it would suffice to try to tile bigger and bigger patterns until obtaining one that tiles periodically). ولكن تلميذه، روبرت برگر، بنى بعد عامين فئة من نحو 20,000 بلاطة مربعة (تسمى الآن بلاطات وانگ) which can tile the plane but not in a periodic fashion. As the number of known aperiodic sets of tiles grew, each set seemed to contain even fewer tiles than the previous one. In particular, Roger Penrose proposed in 1976 a set of just two tiles, up to rotation, (referred to as بلاطات پنروز) that produced only non-periodic tilings of the plane. These tilings displayed instances of fivefold symmetry. In hindsight, similar patterns were observed in some decorative tilings devised by medieval Islamic architects.[7][8] Alan Mackay showed in 1982 experimentally that the diffraction pattern from the Penrose tiling had a two-dimensional Fourier transform consisting of sharp 'delta' peaks arranged in a fivefold symmetric pattern.[9] Around the same time, Robert Ammann had created a set of aperiodic tiles that produced eightfold symmetry. These two examples of mathematical quasicrystals have been shown to be derivable from a more general method which treats them as projections of a higher-dimensional lattice. Just as the simple curves in the plane can be obtained as sections from a three-dimensional double cone, various (aperiodic or periodic) arrangements in 2 and 3 dimensions can be obtained from postulated hyperlattices with 4 or more dimensions. Icosahedral quasicrystals in 3 dimensions as found by Dan Shechtman were projected from a 6 dimensional hypercubic lattice by Peter Kramer and Roberto Neri in 1984.[10] The tiling is formed by two tiles with rhombohedral shape.

وقد بدأ تاريخ أشباه البلورات بورقة بحثية في عام 1984 بعنوان "Metallic Phase with Long-Range Orientational Order and No Translational Symmetry" حيث عرض د. شكتمان ورفاقه نمط حيود واضح بتناظر خماسي الطيات. The pattern was recorded from an Al-Mn alloy which has been rapidly cooled after melting.[2] Next year, Ishimasa et al. reported twelvefold symmetry in Ni-Cr particles.[11] Soon, eightfold diffraction pattern has been recorded in V-Ni-Si and Cr-Ni-Si alloys.[12] Over the years, hundreds of quasicrystals with various compositions and different symmetries have been discovered. The first quasicrystalline materials were thermodynamically unstable – when heated, they formed regular crystals. However in 1987, the first of many stable quasicrystals were discovered, making it possible to produce large samples for study and opening the door to potential applications. In 2009, a mineralogical finding offered evidence that quasicrystals might form naturally under suitable geological conditions.[13] A sample from a Russian holotype specimen was found to be an agglomerate of grains up to 0.1 millimeter in size of various phases, mostly khatyrkite, cupalite (zinc or iron containing), some yet unidentified Al-Cu-Fe minerals and the Al63Cu24Fe13 quasicrystal phase. The quasicrystal grains were of high crystalline quality equal to that of the best laboratory specimens.[14]

In 1972, de Wolf and van Aalst[15] reported that the diffraction pattern produced by a crystal of sodium carbonate cannot be labeled with three indexes but needed one more, which implied that the underlying structure had four dimensions in reciprocal space. Other puzzling cases have been reported, but until the concept of quasicrystal came to be established they were explained away or denied. However, at the end of the 1980s, the idea became acceptable and in 1991 the International Union of Crystallography amended its definition of crystal, reducing it to the ability to produce a clear-cut diffraction pattern and acknowledging the possibility of the ordering to be either periodic or aperiodic.[16] Now the symmetries compatible with translations are defined as "crystallographic", leaving room for other "non-crystallographic" symmetries. Thus aperiodic or quasiperiodic structures can be divided into two main classes: those with crystallographic point-group symmetry, to which the incommensurately modulated structures and composite structures belong, and those with non-crystallographic point-group symmetry, to which quasicrystal structures belong.

The term 'quasicrystal' was first used in print shortly after the announcement of Shechtman's discovery, in a paper by Steinhardt and Levine.[17] However, the adjective 'quasicrystalline' has been loosely applied to any pattern with unusual symmetry.[8][18]

وقد فاز شكتمان بجائزة نوبل في الكيمياء في 2011 لعمله في أشباه البلورات.[19]

الوصف الرياضي

There are several ways to mathematically define quasicrystalline patterns. One definition, the "cut and project" construction, is based on the work of Harald Bohr.[20] Bohr showed that quasiperiodic functions arise as restrictions of high-dimensional periodic functions to an irrational slice (an intersection with one or more hyperplanes), and discussed their Fourier point spectrum. In order that the quasicrystal itself be aperiodic, this slice must avoid any lattice plane of the higher-dimensional lattice. De Bruijn showed that Penrose tilings can be viewed as two-dimensional slices of five-dimensional hypercubic structures.[21] Equivalently, the Fourier transform of such a quasicrystal is nonzero only at a dense set of points spanned by integer multiples of a finite set of basis vectors (the projections of the primitive reciprocal lattice vectors of the higher-dimensional lattice).[22]

The intuitive considerations obtained from simple model aperiodic tilings are formally expressed in the concepts of Meyer and Delone sets. The mathematical counterpart of physical diffraction is the Fourier transform and the qualitative description of a diffraction picture as 'clear cut' or 'sharp' means that singularities are present in the Fourier spectrum.There are different methods to construct model quasicrystals. These are the same methods that produce aperiodic tilings with the additional constraint for the diffractive property. Thus for a substitution tiling the eigenvalues of the substitution matrix should be Pisot numbers. The aperiodic structures obtained by the cut-and-project method are made diffractive by choosing a suitable orientation for the construction. This is indeed a geometric approach which has also a great appeal for physicists.

Classical theory of crystals reduces crystals to point lattices where each point is the center of mass of one of the identical units of the crystal. The structure of crystals can be analyzed by defining an associated group. Quasicrystals, on the other hand, are composed of more than one type of unit, so instead of lattices, quasilattices must be used. Instead of groups, groupoids, the mathematical generalization of groups in category theory, is the appropriate tool for studying quasicrystals.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Using mathematics for construction and analysis of quasicrystal structures is a difficult task for most experimentalists. Computer modeling, based on the existing theories of quasicrystals, however greatly facilitated this task. Advanced programs have been developed[23] allowing one to construct, visualize and analyze quasicrystal structures and their diffraction patterns.

علم مواد أشباه البلورات

Since the original discovery of Shechtman, hundreds of quasicrystals have been reported and confirmed. Undoubtedly, the quasicrystals are no longer a unique form of solid; they exist universally in many metallic alloys and some polymers. Quasicrystals are found most often in aluminium alloys (Al-Li-Cu, Al-Mn-Si, Al-Ni-Co, Al-Pd-Mn, Al-Cu-Fe, Al-Cu-V, etc.), but numerous other compositions are also known (Cd-Yb, Ti-Zr-Ni, Zn-Mg-Ho, Zn-Mg-Sc, In-Ag-Yb, Pd-U-Si, etc.).[24]

نظرياً، يوجد نوعان من أشباه البلورات.[23] النوع الأول، polygonal (dihedral) quasicrystals, have an axis of 8, 10, or 12-fold local symmetry (octagonal, decagonal, or dodecagonal quasicrystals, respectively). They are periodic along this axis and quasiperiodic in planes normal to it. The second type, icosahedral quasicrystals, are aperiodic in all directions.

Regarding thermal stability, three types of quasicrystals are distinguished:[25]

- stable quasicrystals grown by slow cooling or casting with subsequent annealing,

- metastable quasicrystals prepared by melt-spinning, and

- metastable quasicrystals formed by the crystallization of the amorphous phase.

Except for the Al–Li–Cu system, all the stable quasicrystals are almost free of defects and disorder, as evidenced by x-ray and electron diffraction revealing peak widths as sharp as those of perfect crystals such as Si. Diffraction patterns exhibit fivefold, threefold, and twofold symmetries, and reflections are arranged quasiperiodically in three dimensions.

أصل آلية الاستقرار يختلف لأشباه البلورات المستقرة عن تلك فوق المستقرة. Nevertheless, there is a common feature observed in most quasicrystal-forming liquid alloys or their undercooled liquids: a local icosahedral order. The icosahedral order is in equilibrium in the liquid state for the stable quasicrystals, whereas the icosahedral order prevails in the undercooled liquid state for the metastable quasicrystals.

للاستزادة

انظر أيضاً

الكتب المرجعية

- V.I. Arnold, Huygens and Barrow, Newton and Hooke: Pioneers in mathematical analysis and catastrophe theory from evolvents to quasicrystals, Eric J.F. Primrose translator, Birkhäuser Verlag (1990) ISBN 3-7643-2383-3 .

- Christian Janot, Quasicrystals – a primer, 2nd ed. Oxford UP 1997.

- Hans-Rainer Trebin (editor), Quasicrystals, Wiley-VCH. Weinheim 2003.

- Marjorie Senechal, Quasicrystals and geometry, Cambridge UP 1995.

- Jean-Marie Dubois, Useful quasicrystals, World Scientific, Singapore 2005.

- Walter Steurer, Sofia Deloudi, Crystallography of quasicrystals, Springer, Heidelberg 2009.

- Ron Lifshitz, Dan Shechtman, Shelomo I. Ben-Abraham (editors), Quasicrystals: The Silver Jubilee, Philosophical Magazine Special Issue 88/13-15 (2008).

- Peter Kramer and Zorka Papadopolos (editors), Coverings of discrete quasiperiodic sets: theory and applications to quasicrystals, Springer. Berlin 2003.

- Barber, Enrique Macia (2010). Aperiodic Structures in Condensed Matter: Fundamentals and Applications. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-142-006-827-6.

وصلات مكثفة

- A Partial Bibliography of Literature on Quasicrystals (1996–2008).

- BBC webpage showing pictures of Quasicrystals

- What is... a Quasicrystal?, Notices of the AMS 2006, Volume 53, Number 8

- Gateways towards quasicrystals: a short history by P. Kramer

- Quasicrystals: an introduction by R. Lifshitz

- Quasicrystals: an introduction by S. Weber

- Steinhardt's proposal

الهامش

- ^ Steurer W., Z. Kristallogr. 219 (2004) 391–446

- ^ أ ب Shechtman, D.; Blech, I.; Gratias, D.; Cahn, J. (1984). "Metallic Phase with Long-Range Orientational Order and No Translational Symmetry". Physical Review Letters. 53 (20): 1951. Bibcode:1984PhRvL..53.1951S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.53.1951.

- ^ http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/2011/

- ^ 'Impossible' Form of Matter Takes Spotlight In Study of Solids (New York Times) http://www.nytimes.com/1989/09/05/science/impossible-form-of-matter-takes-spotlight-in-study-of-solids.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm

- ^ Technion’s Shechtman Wins Chemistry Nobel for Discovery of Quasicrystals http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-10-05/technion-s-shechtman-wins-chemistry-nobel-for-discovery-of-quasicrystals.html

- ^ Lu, P. J.; Steinhardt, P. J. (2007). "Decagonal and Quasi-Crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture". Science. 315 (5815): 1106–1110. Bibcode:2007Sci...315.1106L. doi:10.1126/science.1135491. PMID 17322056.

- ^ E. Makovicky (1992), 800-year-old pentagonal tiling from Maragha, Iran, and the new varieties of aperiodic tiling it inspired. In: I. Hargittai, editor: Fivefold Symmetry, pp. 67–86. World Scientific, Singapore-London

- ^ أ ب Peter J. Lu and Paul J. Steinhardt (2007). "Decagonal and Quasi-crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture" (PDF). Science. 315 (5815): 1106–1110. Bibcode:2007Sci...315.1106L. doi:10.1126/science.1135491. PMID 17322056.

- ^ Mackay, A.L. (1982). "Crystallography and the Penrose Pattern". Physica A. 114: 609. Bibcode:1982PhyA..114..609M. doi:10.1016/0378-4371(82)90359-4.

- ^ Kramer, P.; Neri, R. (1984). "On periodic and non-periodic space fillings of E(m) obtained by projection". Acta Crystallographica. A40 (5): 580. doi:10.1107/S0108767384001203.

- ^ Ishimasa, T.; Nissen, H.-U.; Fukano, Y. (1985). "New ordered state between crystalline and amorphous in Ni-Cr particles". Physical Review Letters. 55 (5): 511–513. Bibcode:1985PhRvL..55..511I. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.55.511. PMID 10032372.

- ^ Wang, N.; Chen, H.; Kuo, K. (1987). "Two-dimensional quasicrystal with eightfold rotational symmetry". Physical Review Letters. 59 (9): 1010–1013. Bibcode:1987PhRvL..59.1010W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.1010. PMID 10035936.

- ^ Bindi, L.; Steinhardt, P. J.; Yao, N.; Lu, P. J. (2009). "Natural Quasicrystals". Science. 324 (5932): 1306–9. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1306B. doi:10.1126/science.1170827. PMID 19498165.

- ^ Steinhardt, Paul; Bindi, Luca (2010). "Once upon a time in Kamchatka: the search for natural quasicrystals". Philosophical Magazine: 1. doi:10.1080/14786435.2010.510457.

- ^ de Wolf, R.M. and van Aalst, W. The four dimensional group of γ-Na2CO3, Acta. Cryst. A 28 (1972) S111

- ^ The concept of 'aperiodic crystal' was coined by Erwin Schrödinger in another context with a somewhat different meaning. In his popular book What is life? in 1944 Schrödinger sought to explain how hereditary information is stored: molecules were deemed too small, amorphous solids were plainly chaotic so it had to be a kind of crystal; as a periodic structure could not encode information it had to be aperiodic. DNA was later discovered and, although not crystalline, it possesses properties predicted by Schrödinger: it is a regular but aperiodic molecule.

- ^ Levine, Dov; Steinhardt, Paul (1984). "Quasicrystals: A New Class of Ordered Structures". Physical Review Letters. 53 (26): 2477. Bibcode:1984PhRvL..53.2477L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.53.2477.

- ^ Edwards, W.; Fauve, S. (1993). "Parametrically excited quasicrystalline surface waves". Physical Review E. 47 (2): R788. Bibcode:1993PhRvE..47..788E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.47.R788.

- ^ "Nobel win for crystal discovery". BBC News. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- ^ Bohr, H. (1925). "Zur Theorie fastperiodischer Funktionen I". Acta Mathematicae. 45: 580. doi:10.1007/BF02395468.

- ^ de Bruijn, N. (1981). "Algebraic theory of Penrose's non-periodic tilings of the plane". Nederl. Akad. Wetensch. Proc. A84: 39.

- ^ J. B. Suck, M. Schreiber, and P. Häussler, Quasicrystals: An Introduction to Structure, Physical Properties, and Applications (Springer: Berlin, 2004)

- ^ أ ب Yamamoto, Akiji (2008). "Software package for structure analysis of quasicrystals". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials (free-download review). 9: 013001. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9a3001Y. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/3/013001.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ MacIá, Enrique (2006). "The role of aperiodic order in science and technology". Reports on Progress in Physics. 69 (2): 397. Bibcode:2006RPPh...69..397M. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/69/2/R03.

- ^ Tsai, An Pang (2008). "Icosahedral clusters, icosaheral order and stability of quasicrystals—a view of metallurgy". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials (free-download review). 9: 013008. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9a3008T. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/1/013008.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help)