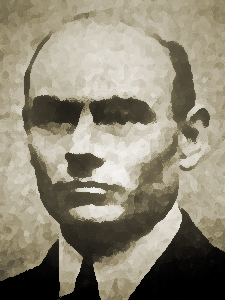

روبرت ماينور

روبرت بركلي "بوب" ماينور Robert Berkeley "Bob" Minor (1884 - 1952)، ويُعرف أيضاً بلقب "Fighting Bob," was a political cartoonist, a radical journalist, and, beginning in 1920, a leading member of the American Communist Party.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

السيرة

النشأة

Robert Minor, best known to those who knew him by the nickname "Bob," was born July 15, 1884, in San Antonio, Texas. Minor came from old and respected family lines. On his father's side, General John Minor had served as Thomas Jefferson's Presidential campaign manager; his mother was related to General Sam Houston, first President of the Republic of Texas.[1] His father was a school teacher and lawyer, later elected as a judge,[2] while his maternal grandfather was a doctor.[3]

Despite the notable family forefathers, Bob Minor was not brought up with a silver spoon in his mouth — rather he was the product of what one historian has called "the hard-up, run-down middle class," living in an "unpainted frontier cottage in San Antonio."[3] Minor was unable to begin school until age 10 due to his family's dire financial straits before leaving school at age 14 to take a job as a Western Union messenger boy to help support his family.[4] Minor left home two years later, going to work at a variety of different jobs, including time spent as a sign painter, a carpenter, a farm worker, and a railroad laborer.[5]

In 1904, at the age of twenty, Robert Minor was hired as an assistant stereotypist and handyman at the San Antonio Gazette, where he developed his artistic talent in his spare time. Minor emerged as an accomplished political cartoonist.

Minor moved to St. Louis to take a position as a cartoonist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Minor's work, initially very conventional in form using pen-and-ink, was transformed by his move to the use of grease crayon on paper. Minor gained recognition as the chief cartoonist at the Post-Dispatch and was considered by many to be among the best in the country.

In 1911, Robert Minor was hired by the New York World, where he became the highest paid cartoonist in the United States.[6] His father was on a parallel path of advancement, transformed by a 1910 election "from an unsuccessful lawyer to an influential district judge."[7]

العمل الصحفي

هذا الرسم كاد يجر صاحبه إلى السجن سنة 1916 خلال الحرب العالمية الأولى كانت الولايات المتحدة توسعت فى التجنيد بأعداد كبيرة وعارض الرسام روبرت مينور الحرب فصور طبيب الكشف على الجنود يهتمم بالقوة البدنية ويفضل من لاعقل له فهو المطلوب مطيعا للاوامر بلا تفكيرويقول أخيرا وجدت الجندى الكامل.

In 1907 Minor joined the Socialist Party of America but by the beginning of 1912 he had moved towards an anarchist orientation and support of revolutionary industrial unionism.[8]

Minor had saved several hundred dollars earned in St. Louis and decided that he wanted to go to Paris to attend art school to perfect his craft. In France he enrolled in a class at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, the French national art school, but he found the experience unsatisfying.[9] Minor spent the rest of his time in Paris studying art on his own and taking part in the left wing labor movement through the Socialist Party of France.[9] Minor returned to the United States in 1914, just prior to the outbreak of World War I.

The year 1914 saw Minor in the unusual position of being paid but unable to work, with an old contract he had signed with the New York World continuing to pay him a salary merely to keep him from drawing for other papers.[10] However, with the outbreak of hostilities in August Minor began to make a series of aggressive and provocative cartoons attacking both sides of the European conflict for their imperialism. While The World initially began to use these cartoons, it was not long before Minor came to the banks of the Rubicon, when his employer demanded that the artist begin to draw pro-war panels. Minor was unalterably opposed to the World War and was faced with a choice between his paycheck and his beliefs. His convictions won and Minor was successful in having his contract with The World annulled.[10]

On June 1, 1915, Minor moved to the New York Call, a Socialist Party-affiliated daily broadsheet.[11] Minor also began contributing aggressively anti-war cartoons to Max Eastman's radical New York monthly, The Masses. Minor's radical cartoons would later provide fodder for the United States government's prosecution of The Masses for alleged violation of the Espionage Act of 1917, a legal assault which would eventually lead to the demise of the magazine. Minor was sent as a war correspondent of The Call to Europe, where he wrote from France and Italy. Part of Minor's European expenses were being borne by a liberal newspaper syndicate in exchange for use of his drawings from the front. The syndicate found themselves unable to use the radical material which Minor was by this time producing and The Call was forced to recall him from Europe.[10]

In 1916, Minor was dispatched by The Call to Mexico to cover the American intervention there.[10] When the "Mexican War" came to a sudden conclusion, Minor went to California for a rest. There he became deeply involved in the defense campaign of radical trade unionists Tom Mooney and Warren Billings in their highly publicized legal case accusing them of bombing of the 1916 San Francisco "Preparedness Day" parade. Minor worked full-time for a year and a half as the publicity director for the International Workers Defense League, an organization established to provide legal support and build public sympathy for Mooney and Billings and their co-defendants. Minor authored several pamphlets in 1917 and 1918 and spoke to a wide range of audiences about the alleged "frame-up" being perpetrated on the radical trade unionists.[12]

The Call, dispatched Minor to Europe as a war correspondent in 1918, with Minor continuing to contribute material on the European revolutionary movement to the successor to The Masses, The Liberator. In May 1918 Minor arrived in Soviet Russia, where he remained until November. While there, he met Lenin and wrote anti-war propaganda for distribution to English-speaking troops involved in the invasion of Soviet Russia.[13] The experience proved to be a watershed for Minor, winning him over to the cause of communism. Minor later traveled to Germany, where he saw the German Revolution firsthand, and thereafter to France.

While in Paris in 1919, Minor was arrested and charged with treason for advising French railway workers to strike against the shipment of munitions to interventionist forces in Soviet Russia.[12] Minor was shipped out to Germany, where he was confined in the American military prison at Coblenz, Germany for several weeks,[12] eventually gaining his release due in large measure to political pressure exerted by his well-connected family in America.[14]

السيرة السياسية

Upon his return to the America in 1920, Minor immediately joined the underground American Communist Party.[13] Minor was a supporter of the United Communist Party in the convoluted factional struggle of the day, joining the newly unified Communist Party of America (CPA) along with the rest of his organization when the UCP merged with the old CPA in the spring of 1921.[15]

الوفاة والذكرى

Bob Minor suffered a heart attack in 1948 and was bedridden during the time of McCarthyism when his fellow leaders of the American Communist Party were arrested and imprisoned. Owing to his frail health, the United States government chose not to proceed against him. He died in 1952, survived by his wife, the artist Lydia Gibson. The couple had no children.

Minor is remembered by some as the inspiration for the fictional character "Don Stevens" in John Dos Passos' trilogy USA.[16]

The historian Theodore Draper opined:

"Minor is a study in extremes. A truly gifted and powerful cartoonist, he renounced art for politics. He made this gesture of total subservience to politics after years as an anarchist despising and denouncing politics. But he could not transfer his genius from art to politics. The stirring drawings were replaced by boring and banal speeches. He had none of the gifts of the natural politician, his stock in trade was limited to platitudes and slogans. The wild man, tamed, became a political hack. If as an anarchist he had believed that politics was a filthy business, as a Communist he still seemed to believe it was — only now it was his business."[17]

Robert Minor's papers are housed in the Rare Book & Manuscript section on the 6th floor of Butler Library at Columbia University. Approximately 15,000 items are included in the collection, which is housed in some 65 archival boxes.[18]

الهامش

- ^ Theodore Draper, The Roots of American Communism. New York: Viking Press, 1957; pg. 121.

- ^ Solon DeLeon (ed.), The American Labor Who's Who. New York: Hanford Press, 1925; pg. 162.

- ^ أ ب Draper, The Roots of American Communism, pg. 121.

- ^ "Philip Sterling, "Robert Minor: The Life Story of New York's Communist Candidate for Mayor," The Daily Worker, vol. 10, no. 218 (September 11, 1933), pg. 5.

- ^ DeLeon, The American Labor Who's Who, pg. 162.

- ^ Draper, The Roots of American Communism, pg. 122, citing Minor's "official biographer."

- ^ Draper, The Roots of American Communism, pg. 122.

- ^ Branko Lazitch and Milorad M. Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern: New, Revised, and Expanded Edition. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1986; pg. 318.

- ^ أ ب Philip Sterling, "Robert Minor: The Life Story of New York's Communist Candidate for Mayor, Part 3," The Daily Worker, vol. 10, no. 221 (September 14, 1933), pg. 5.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Philip Sterling, "Robert Minor: The Life Story of New York's Communist Candidate for Mayor, Part 4," The Daily Worker, vol. 10, no. 222 (September 15, 1933), pg. 5.

- ^ "'Bob' Minor," New York Call, vol. 8, no. 152 (June 1, 1915), pg. 1.

- ^ أ ب ت DeLeon (ed.), The American Labor Who's Who, pg. 162.

- ^ أ ب Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 318.

- ^ Minor's father, Robert B. Minor, was by then a judge of the 57th Texas State Judicial Circuit Court.

- ^ For information on the factional divisions of the American Communist movement, see Early American Marxism website, "The Communist Party of America (1919-1946): Party History" at http://www.marxisthistory.org/subject/usa/eam/communistparty.html

- ^ Dee Garrison, Mary Heaton Vorse: The Life of an American Insurgent. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989. Page 186.

- ^ Draper, The Roots of American Communism, pg. 126.

- ^ "Rober Minor papers, 1907-1952," Butler Library, Columbia University, collection no. Ms Coll\Minor.

ببليوگرافيا

كتب وملازم

- War Pictures. New York: The New York Call, c.1916.

- The Frame-Up System: Story of So-Called Bomb Trials in San Francisco. San Francisco: International Worker's Defense League, 1917.

- Fickert has Ravished Justice: Story of So-Called Bomb Trials in San Francisco. San Francisco: International Worker's Defense League, 1917.

- Shall Mooney Hang?: Justice Raped in California. San Francisco: International Worker's Defense League, c.1918.

- Stedman's Red Raid. Cleveland: Toiler Publishing Association, 1920. Also available at the Marxist Internet Archive.

- "Resolved: That the Terms of the Third International are Inacceptable to the Revolutionary Socialists of the World": Being the Report of a Debate, Held in Star Casino, New York City, Sunday, January Sixteenth, 1921: Affirmative James Oneal vs. Negative Robert Minor. New York: Academy Press, 1921.

- The Struggle Against War: And the Peace Policy of the Soviet Union. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1936.

- The Fight Against Hitlerism. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1941. (With William Z. Foster.)

- One War to Defeat Hitler. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1941.

- Free Earl Browder!. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1941.

- The Year of Great Decision, 1942. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1942.

- Our Ally: The Soviet Union. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1942.

- Invitation to Join the Communist Party. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1943.

- The Heritage of the Communist Political Association. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1944.

- Lynching and Frame-up in Tennessee. New York: Workers Library Publishers, 1946.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

أعمال أسهم فيها

- Red Cartoons of 1926: From The Daily Worker and the Workers Monthly. New York: The Daily Worker Publishing Company, 1926. Also available from Marxist Internet Archive.

- Red Cartoons of 1927: From The Daily Worker and the Workers Monthly. New York: The Daily Worker Publishing Company, 1927. Also available from Marxist Internet Archive.

- Red Cartoons of 1928: From The Daily Worker and the Workers Monthly. New York: The Daily Worker Publishing Company, 1928. Also available from Marxist Internet Archive.

مقالات

- "Have You A Country?". Revolt, Vol. 1, No. 2 (January 15, 1916), pp. 6–7.

- "Our 'C.E.': In Memory of C.E. Ruthenberg, July 9, 1882–March 2, 1927". The Communist, Vol. 14, No. 3 (March 1935), pp. 217–226. OCLC 35811669 Full issue available at Marxist Internet Archive.

مقالات من كتاب آخرين

- North, Joseph. “‘Fighting Bob’ Minor” (Eulogy). Masses and Mainstream (1953), pp. 15–28.

وصلات خارجية

- مواليد 1884

- وفيات 1952

- American editorial cartoonists

- American Comintern people

- اشتراكيون أمريكان

- American communists

- American Marxists

- أعضاء الحزب الاشتراكي الأمريكي

- Members of the Communist Party USA

- American male journalists

- Marxist journalists

- أمريكان في الحرب الأهلية الاسبانية

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- People from San Antonio

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch people