خاكوبو آربنز

- هذا اسم إسباني; لا يتضمن اسم العائلة.

Jacobo Árbenz | |

|---|---|

| |

| 25 رئيس گواتيمالا | |

| في المنصب 15 مارس 1951 – 27 يونيو 1954 | |

| سبقه | خوان خوسيه أريڤالو |

| خلـَفه | كارلوس إنريكى دياز دى ليون |

| وزير الدفاع الوطني الأول | |

| في المنصب 15 مارس 1945 – 15 مارس 1951 | |

| الرئيس | خوان خوسيه أريڤالو |

| سبقه | منصب مستحدث |

| خلـَفه | كارلوس إنريكى دياز دى ليون |

| رأس دولة وحكومة گواتيمالا | |

| في المنصب 20 أكتوبر 1944 – 15 مارس 1945 يخدم with Francisco Javier Arana و Jorge Toriello | |

| سبقه | Federico Ponce Vaides |

| خلـَفه | خوان خوسيه أريڤالو |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán سبتمبر 14, 1913 كوِتزالتنانگو، گواتيمالا |

| توفي | يناير 27, 1971 (aged 57) مدينة المكسيك، المكسيك |

| الحزب | Revolutionary Action Party |

| الزوج | |

| الأنجال | 3، منهم أرابلا |

| المدرسة الأم | مدرسة البوليتكنيك |

| المهنة | جندي |

| التوقيع |  |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | الموقع الرسمي (لذكراه) |

| الخدمة العسكرية | |

| الولاء | |

| الفرع/الخدمة | الجيش الگواتيمالي |

| سنوات الخدمة | 1932–1954 |

| الرتبة | عقيد |

| الوحدة | حرس الشرف |

| المعارك/الحروب | الثورة الگواتيمالية محاولة الانتفاضة العسكرية 1949 انقلاب گواتيمالا 1954 |

العقيد خاكوبو آربنز گوزمان (Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán ؛ النطق الإسپاني: [xaˈkoβo ˈarβenz ɣuzˈman]؛ 14 سبتمبر 1913 – 27 يناير 1971)، كنيته الأشقر الكبير (إسپانية: El Chelón) أو السويسري (إسپانية: El Suizo) لأصوله السويسرية، كان ضابطاً گواتيمالياً وثاني رئيس لگواتيمالا منتخب ديمقراطياً، وشغل المنصب من 1951 حتى 1954. كما كان وزير الدفاع من 1944 حتى 1951. وقد كان شخصية بارزة في الثورة الگواتيمالية التي استمرت عشر سنوات، والتي مثلت بعض السنوات القليلة من الديمقراطية التمثيلية في تاريخ گواتيمالا. برنامج الإصلاح الزراعي ذائع الصيت، الذي شرّعه آربنز كرئيس كان له تأثير هائل في أرجاء أمريكا اللاتينية.[1]

وُلِد آربنز في 1913 في أسرة من الطبقة المتوسطة، أبوه ألماني سويسري وأمه گواتيمالية. وقد تخرج with high honors from a military academy in 1935, and served in the army until 1944, quickly rising through the ranks. During this period, he witnessed the violent repression of agrarian laborers by the الولايات المتحدة-backed dictator Jorge Ubico, and was personally required to escort chain-gangs of prisoners, an experience that radicalized him. In 1938 he met and married his wife María Villanova, who was a great ideological influence on him, as was José Manuel Fortuny, a Guatemalan communist. In October 1944 several civilian groups and progressive military factions led by Árbenz and Francisco Arana rebelled against Ubico's repressive policies. In the elections that followed, Juan José Arévalo was elected president, and began a highly popular program of social reform. Árbenz was appointed Minister of Defense, and played a crucial role in putting down a military coup in 1949.[2][3][4][5]

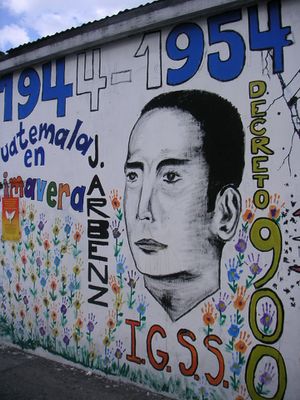

After the death of Arana, Árbenz contested the presidential elections that were held in 1950 and without significant opposition defeated Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, his nearest challenger, by a margin of over 50%. He took office on March 15, 1951, and continued the social reform policies of his predecessor. These reforms included an expanded right to vote, the ability of workers to organize, legitimizing political parties, and allowing public debate.[6] The centerpiece of his policy was an agrarian reform law under which uncultivated portions of large land-holdings were expropriated in return for compensation and redistributed to poverty-stricken agricultural laborers. Approximately 500,000 people benefited from the decree. The majority of them were indigenous people, whose forebears had been dispossessed after the Spanish invasion.

His policies ran afoul of the شركة يونايتد فروتس, which lobbied the الولايات المتحدة government to have him overthrown. The US was also concerned by the presence of communists in the Guatemalan government, and Árbenz was ousted in the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état engineered by the US Department of State and the Central Intelligence Agency. Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas replaced him as president. Árbenz went into exile through several countries, where his family gradually fell apart. His daughter committed suicide, and he descended further into alcoholism, eventually dying in Mexico in 1971. In October 2011, the Guatemalan government issued an official apology for Árbenz's overthrow.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

النشأة

وُلِد آربنز في كتسالتنانگو، گواتيمالا، ثاني أكبر مدن البلد، في 1913. وكان أبوه صيدلياً ألماني سويسري، واسمه أيضاً خاكوبو آربنز،[7] هاجر إلى گواتيمالا في 1901. وكانت أمه من عرق اللادينو من الطقبقة الوسطى. عائلته كانت نسبياً ميسورة الحال من الطبقة العليا؛ وطفولته وُصِفت بأنها كانت "مرتاحة".[8] وفي وقت ما أثناء طفولته، أدمن أبوه المورفين وبدأ في إهمال شئون العائلة. He eventually went bankrupt, forcing the family to move to a rural estate that a wealthy friend had set aside for them "out of charity". Jacobo had originally desired to be an economist or an engineer, but since the family was now impoverished, he could not afford to go to a university. He initially did not want to join the military, but there was a scholarship available through the Escuela Politécnica for military cadets. He applied, passed all of the entrance exams, and entered as a cadet in 1932. His father committed suicide two years after Árbenz entered the academy.[8]

ثورة أكتوبر ووزارة الدفاع

ثورة أكتوبر

الرئاسة

الاصلاح الزراعي

The biggest component of Árbenz's project of modernization was his agrarian reform bill.[9] Árbenz drafted the bill himself with the help of advisers that included some leaders of the communist party as well as non-communist economists.[10] He also sought advice from numerous economists from across Latin America.[9] The bill was passed by the National Assembly on June 17, 1952, and the program went into effect immediately. The focus of the program was on transferring uncultivated land from large landowners to their poverty-stricken laborers, who would then be able to begin a viable farm of their own.[9] Árbenz was also motivated to pass the bill because he needed to generate capital for his public infrastructure projects within the country. At the behest of the United States, the World Bank had refused to grant Guatemala a loan in 1951, which made the shortage of capital more acute.[11]

العلاقة مع شركة يونايتد فروتس

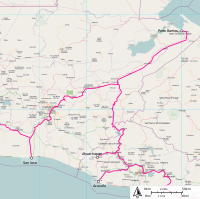

الانقلاب

حياته اللاحقة

بداية المنفى

انتحار ابنته ووفاته

After the Cuban Revolution of 1959, a representative of the Fidel Castro government asked Árbenz to come to Cuba, to which he readily agreed, sensing an opportunity to live with fewer restrictions on himself. He flew to Havana in July 1960, and, caught up in the spirit of the recent revolution, began to participate in public events.[12] His presence so close to Guatemala once again increased the negative coverage he received in the Guatemalan press. He was offered the leadership of some revolutionary movements in Guatemala but refused, as he was pessimistic about the outcome.[12]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

اعتذار الحكومة الگواتيمالية

In May 2011 the Guatemalan government signed an agreement with Árbenz's surviving family to restore his legacy and publicly apologize for the government's role in ousting him. This included a financial settlement to the family. The formal apology was made at the National Palace by Guatemalan President Alvaro Colom on October 20, 2011, to Jacobo Árbenz Villanova, the son of the former president, and a Guatemalan politician.[13] Colom stated, "It was a crime to Guatemalan society and it was an act of aggression to a government starting its democratic spring."[13] The agreement established several forms of reparation for the next of kin of Árbenz Guzmán. Among other measures, the state:[13][14]

- held a public ceremony recognizing its responsibility

- sent a letter of apology to the next of kin

- named a hall of the National Museum of History and the highway to the Atlantic after the former president

- revised the basic national school curriculum (Currículo Nacional Base)

- established a degree program in Human Rights, Pluriculturalism, and Reconciliation of Indigenous Peoples

- held a photographic exhibition on Árbenz Guzmán and his legacy at the National Museum of History

- recovered the wealth of photographs of the Árbenz Guzmán family

- published a book of photos

- reissued the book Mi esposo, el presidente Árbenz (My Husband President Árbenz)

- prepared and published a biography of the former President, and

- issued a series of postage stamps in his honor.

The official statement issued by the government recognized its responsibility for "failing to comply with its obligation to guarantee, respect, and protect the human rights of the victims to a fair trial, to property, to equal protection before the law, and to judicial protection, which are protected in the American Convention on Human Rights and which were violated against former President Juan Jacobo Árbenz Guzman, his wife, María Cristina Villanova, and his children, Juan Jacobo, María Leonora, and Arabella, all surnamed Árbenz Villanova."[14]

الذكرى

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

الهامش

- ^ Gleijeses 1992, p. 3.

- ^ Martínez Peláez 1990, p. 842.

- ^ LaFeber 1993, p. 77–79.

- ^ Forster 2001, p. 81–82.

- ^ Friedman 2003, p. 82–83.

- ^ Hunt 2004, p. 255.

- ^ Garcia Ferreira 2008, p. 60.

- ^ أ ب Gleijeses 1992, p. 134–137.

- ^ أ ب ت Immerman 1982, pp. 64–67.

- ^ Gleijeses 1992, pp. 144–146.

- ^ Gleijeses 1992, pp. 149–164.

- ^ أ ب Garcia Ferreira 2008, p. 72–73.

- ^ أ ب ت Malkin 2011.

- ^ أ ب IACHR 2011.

المصادر

- Borrayo Pérez, Gloria Catalina (2011). Análisis de contenido de la película "El Silencio de Neto" con base a los niveles histórico, contextual, terminológico, de presentación y el análisis de textos narrativos (PDF). Tesis (in الإسبانية). Guatemala: Escuela de Ciencias de la Comunicación de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chomsky, Noam (1985). Turning the Tide. Boston, Massachusetts: South End Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cullather, Nicholas (2006). Secret History: The CIA's Classified Account of its Operations in Guatemala 1952–54 (2nd ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5468-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Forster, Cindy (2001). The time of freedom: campesino workers in Guatemala's October Revolution. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-4162-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fried, Jonathan L. (1983). Guatemala in rebellion: unfinished history. Grove Press. p. 52.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Friedman, Max Paul (2003). Nazis and good neighbors: the United States campaign against the Germans of Latin America in World War II. Cambridge University Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0-521-82246-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gaddis, John Lewis (1997). We Now Know, rethinking Cold War history. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-878070-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Garcia Ferreira, Roberto (2008). "The CIA and Jacobo Arbenz: The story of a disinformation campaign". Journal of Third World Studies. United States. XXV (2): 59.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gleijeses, Piero (1992). Shattered hope: the Guatemalan revolution and the United States, 1944–1954. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02556-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grandin, Greg (2000). The blood of Guatemala: a history of race and nation. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2495-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Handy, Jim (1994). Revolution in the countryside: rural conflict and agrarian reform in Guatemala, 1944–1954. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4438-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hunt, Michael (2004). The World Transformed. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-937234-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "IACHR Satisfied with Friendly Settlement Agreement in Arbenz Case Involving Guatemala". Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- Ibarra, Carlos Figueroa (June 2006). "The culture of terror and Cold War in Guatemala". Journal of Genocide Research. 8 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1080/14623520600703081.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Immerman, Richard H. (1982). The CIA in Guatemala: The Foreign Policy of Intervention. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71083-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Koeppel, Dan (2008). Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World. New York: Hudson Street Press. p. 153.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kornbluh, Peter; Doyle, Kate, eds. (May 23, 1997), "CIA and Assassinations: The Guatemala 1954 Documents", National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 4 (Washington, D.C.: National Security Archive), http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB4/index.html

- LaFeber, Walter (1993). Inevitable revolutions: the United States in Central America. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 77–79. ISBN 978-0-393-30964-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Loveman, Brian; Davies, Thomas M. (1997). The Politics of antipolitics: the military in Latin America (3rd, revised ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8420-2611-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Malkin, Elizabeth (October 20, 2011). "An Apology for a Guatemalan Coup, 57 Years Later". The New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Martínez Peláez, Severo (1990). La Patria del Criollo (in Spanish). México: Ediciones En Marcha. p. 858.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - McCreery, David (1994). Rural Guatemala, 1760–1940. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2318-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Paterson, Thomas G. (2009). American Foreign Relations: A History, Volume 2: Since 1895. Cengage Learning. ISBN 0-547-22569-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - prneswire.com (October 11, 2011). "Guatemalan government issues official apology to deposed former president Jacobo Arbenz's family for Human Rights Violtions, 57 years later". Retrieved September 19, 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|author= - Rabe, Stephen G. (1988). Eisenhower and Latin America: The Foreign Policy of Anticommunism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4204-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sabino, Carlos (2007). Guatemala, la historia silenciada (1944–1989) (in Spanish). Vol. Tomo 1: Revolución y Liberación. Guatemala: Fondo Nacional para la Cultura Económica.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Schlesinger, Stephen; Kinzer, Stephen (1999). Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala. David Rockefeller Center series on Latin American studies, Harvard University. ISBN 978-0-674-01930-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schlesinger, Stephen (June 3, 2011). "Ghosts of Guatemala's Past". The New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Smith, Peter H. (2000). Talons of the Eagle: Dynamics of U.S.-Latin American Relations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512997-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Streeter, Stephen M. (2000). Managing the counterrevolution: the United States and Guatemala, 1954–1961. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-89680-215-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

للاستزادة

الكتب

- Arévalo Martinez, Rafael (1945). ¡Ecce Pericles! (in الإسبانية). Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional.

- Chapman, Peter (2009). Bananas: How the United Fruit Company Shaped the World. Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84767-194-3.

- Cullather, Nicholas (May 23, 1997). "CIA and Assassinations: The Guatemala 1954 Documents". National Security Archive Electronic. Briefing Book No. 4. National Security Archive.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Dosal, Paul J. (1993). Doing Business With the Dictators: A Political History of United Fruit in Guatemala, 1899–1944. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8420-2590-4.

- Handy, Jim (1984). Gift of the devil: a history of Guatemala. South End Press. ISBN 978-0-89608-248-9.

- Holland, Max (2004). "Operation PBHistory: The Aftermath of SUCCESS". International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence. 17: 300–332.

- Jonas, Susanne (1991). The battle for Guatemala: rebels, death squads, and U.S. power (5th ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-0614-8.

تقارير حكومية وغير حكومية

Works related to CIA and Guatemala Assassination Proposals: CIA History Staff Analysis at Wikisource

Works related to CIA and Guatemala Assassination Proposals: CIA History Staff Analysis at Wikisource- CIA file about Operations against Jacob Árbenz

الأخبار

- From Árbenz to Zelaya: Chiquita in Latin America, Democracy Now!, July 21, 2009

- Guatemala to Restore Legacy of a President the US Helped Depose, by Elisabeth Malkin, Published: May 23, 2011

وصلات خارجية

Media related to Jacobo Arbenz Guzman at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jacobo Arbenz Guzman at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to خاكوبو آربنز at Wikiquote

Quotations related to خاكوبو آربنز at Wikiquote- International Jose Guillermo Carrillo Foundation

- Jacobo Árbenz Biography brought to you by the United Fruit Company's "United Fruit Historical Society"

| مناصب سياسية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه خوان خوسيه أريڤالو |

رئيس گواتيمالا 1951–1954 |

تبعه كارلوس إنريكى دياز دى ليون |

خطأ لوا في package.lua على السطر 80: module 'Module:Authority control/auxiliary' not found.

- Articles containing إسپانية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- CS1 الإسبانية-language sources (es)

- CS1 maint: ref duplicates default

- رؤساء گواتيمالا

- عسكريون گواتيماليون

- مواليد 1913

- وفيات 1971

- أشخاص من كتسالتنانگو

- زعماء أطاحت بهم انقلابات

- اشتراكيون گواتيماليون

- الثورة الگواتيمالية

- Revolutionary Action Party politicians

- گواتيماليون من أصل سويسري

- گواتيماليون من أصل ألماني

- گواتيماليون

- گواتيماليو القرن العشرين