حادثة منجم كوپياپو 2010

| أحداث هذه المقالة هي أحداث جارية. المعلومات المذكورة قد تتغير بسرعة مع تغير الحدث. |

جهود الانقاذ في سان خوسيه ده كوپياپو 10 أغسطس 2010 | |||||||||||||||||||

| التاريخ | 5 أغسطس 2010–الآن(5258 days) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الوقت | 18:05 UTC | ||||||||||||||||||

| الموقع | كوپياپو، شيلي | ||||||||||||||||||

| الخسائر | |||||||||||||||||||

| 33 عالقون | |||||||||||||||||||

تقدم عملية الانقاذ

| |||||||||||||||||||

حادث منجم كوپياپو 2010 هو حادث تعدين حدث في 5 أغسطس 2010, عند انهيار منجم نحاس-ذهب, بالقرب من كوپياپو, شيلي, وعلق 33 عامل تحت الأرض.[1][2] وقد ظل العمال العالقون تحت الأرض على قيد الحياة لأطول فترة عن أي حادث آخر مشابه.[3]

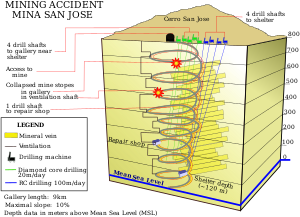

ويقع منجم سان خوسيه على بعد 45 كم شمال كوپياپو، في أقصى شمال شيلي. وعلق العمال على عمق 700 متر تحت الأرض، بعد حدوث مجموعة انعطافات وتحولات في المدخل الرئيسي للمنجم. وقد وقعت عدة حوادث سابقة في المنجم، أدت إلى وفاة شخص واحد.[4] وأفاد تقرير حكومي في يوليو 2010 عن فشل أصحاب المنجم "في تدعيم السقف ...", حيث أدى عدم وجود تدعيمات إلى انهيار مبكر للمنجم. وكان هناك جدل حول السماح باستمرارية العمل في المنجم مع عدم معالجة الشركة المالك القضايا السابقة المتعلقة بالسلامة والأمان واستقالة موظف واحد على الأقل من موظفي الأمان.[بحاجة لمصدر]

بعد انقاذ عمال المناجم في 12 اكتوبر 2010 19:00 بالتوقيت المحلي (23:00 UTC). وكان من المتوقع أن تستغرق العملية 16 ساعة على الأقل.[5]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

خلفية

الحادث

حدث الانهيار في 5 أغسطس 2010, في الساعة 14:00 (بالتوقيت المحلي) كما أفاد مالكو المنجم, the Empresa Minera San Esteban mining company, to national authorities. The rescue efforts started on 6 August supervised by the Chilean Minister of Labour and Social Welfare, the Chilean Undersecretary of Mining, and the director of the SERNAGEOMIN (the National Mining and Geology Service).[6] The Oficina Nacional de Emergencias del Ministerio del Interior (ONEMI – National Emergencies Office of the Interior Ministry) reported that day the names of the 33 miners trapped in the mine,[2] including Franklin Lobos Ramírez, a retired Chilean footballer.[1] One of the miners is Bolivian while the others are Chilean nationality.[1][7] Chilean Minister of Mining, Laurence Golborne, was in Ecuador at the time of the disaster and arrived at the disaster site on 7 August.[6]

When the collapse occurred, there were two groups of miners.[بحاجة لمصدر] The main group of 33 miners was deep inside the mine and included several workers, some subcontracted employees of a different company, who would not normally have been with them.[بحاجة لمصدر] A second group of miners was near or at the entrance of the mine and escaped immediately without incident. A dust cloud occurred during the collapse, blinding many miners for six hours and causing lingering eye irritation and burning.[8] The trapped group of miners tried to escape through a ventilation shaft system, but the ladders required by mining safety codes were missing and the shaft later became unusable during subsequent geological movements.[9] The company had previously been ordered by supervisory authorities to install ladders after an earlier accident had caused authorities to close the historically accident plagued mine as a condition of restarting operations.[10]

The shift supervisor of the trapped miners, Luis Urzua, recognizing the gravity of the situation and the difficulty of any rescue attempt, if a rescue was even possible, gathered his men in a secure room called a "refuge" and organized the men and meager resources for a long term survival situation. Experienced miners were sent out to assess the situation, men with important skills were tasked with key roles and numerous other measures were taken to ensure the survival of the men during a long-term entrapment.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Search and rescue attempts

Ventilation shaft

Rescuers attempted to bypass the rockfall on the main entryway through alternative passages but each route was blocked by fallen rock or threatened by ongoing rock movement. A second collapse occurred at the stricken mine on August 7 when rescuers were trying to gain access via a ventilation shaft and they were forced to use heavy machinery.[بحاجة لمصدر] Out of concern that additional attempts pursuing this route would cause further geological movement within the mine, attempts to reach the trapped miners through previously existing shafts were halted and other means to find them were sought.[11] Due to the worsening situation and rising concern by the Chilean population deeply sympathetic to the plight of both the miners and their families, especially following closely on the heels of sharp criticism of the government's handling of the latest Chilean earthquake and tsunami, President Piñera returned to Chile from a presidential inauguration in Colombia to take direct charge of the emergency response and the search for the lost miners.[12]

Exploratory bore holes

Percussion drills (rotary hammer drills) were used to make numerous[بحاجة لمصدر] boreholes about 5.5 inches (15 centimeters) wide to find the miners.[13] The rescue effort was complicated by out-of-date maps and several boreholes drifting off-target because of[14] notoriously hard rock that exacerbated the drill's tendency to drift.[15] On 19 August one of the probes reached the area where the miners were believed to be trapped but found no signs of life.[16]

Discovery

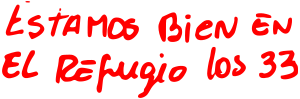

On 22 August at 07:15 (local time), another probe reached a ramp, at 688 meters (2,257 ft) underground, about 20 metres from a shelter where the miners were expected to have taken refuge.[17] The miners had listened to the drills approaching for days and had prepared pre-written notes to their rescuers on the surface as well as making sure they had adhesive tape to secure the prepared notes to the drill once its tip poked into their space. The notes surprised the rescuers when they pulled the drill bit out and discovered the letters; the miners having survived longer then anyone had expected.[18] At 15:17 (local time) President Sebastián Piñera showed the media the note after it had been placed in a document protector, sent from the miners' shelter far below, written on a piece of paper with a red marker, that confirmed the miners were alive.

The note read: "Estamos bien en el refugio los 33" (English: "The 33 of us are fine in the shelter").[19]

Hours later, cameras sent down the bore hole made contact with the miners, taking the first images of the trapped workers.[20] The miners had a 50 square meter shelter with two long benches,[21] but ventilation problems had led them to move out to a tunnel.[22] In addition to the shelter, they had some 2 km of galleries in which to move around.[8] The miners used backhoes to dig for trapped water.[23] Some water was obtained from the radiators of vehicles inside the mineshaft.[8] Health officials are running tests on the water.[8] Food supplies were limited, and the men may have lost 8 to 9 kg (17–20 pounds) each.[22] Although the emergency supplies were intended for only two or three days, the miners rationed them to last for 17 days until contact with the surface.[24] They consumed "two little spoonfuls of tuna, a sip of milk and a biscuit every 48 hours" and a morsel of peach.[8][23] They used the batteries of a truck to power their helmet lamps.[22]

Health of miners

On 23 August voice contact was made with the miners. They reported having few medical problems. The doctor in charge of the rescue operation reported to the media that "they have considerably less discomfort than we might have expected after spending 18 days inside the mine, at 700 metres deep and under high temperatures and high humidity". The doctors also reported that they already have been provided with a 5% glucose solution and a drug to prevent stomach ulcers resulting from food deprivation.[25] Material is sent down in 5-foot-long (1.5 m) blue plastic capsules nicknamed palomas ("doves"), taking an hour to reach the miners.[21][26] Engineers coated the boreholes with a gel in order to ensure the integrity of the shafts and ease the passage of the capsules.[27] In addition to high-energy glucose gels, rehydration tablets, and medicine, rescuers also sent down oxygen after the miners reported there was not enough air.[26] Delivery of solid food began a few days later.[26][28] Two other boreholes were completed—one for enriched oxygen, the second for video conferences to allow daily chats with family members.[28] Relatives may also write letters, but were asked to keep them optimistic.[21]

Out of concern for the miners' mental health, rescuers hesitated to tell the miners that according to the conservative rescue plan, the rescue may take months, with an eventual extraction date close to Christmas. The miners who had been trapped since August would miss many holidays, including the Chilean Bicentennial Celebration and crucial soccer games in addition to their personal anniversaries. The miners were fully informed however, on 25 August the exact prognosis for their rescue and the complexity of the plans to get them out. The mining minister reported that the men took the news well.[29]

Rescue workers and consultants described the miners as a very disciplined group.[15] Psychiatrists and doctors are working with the rescue effort to ensure the miners keep busy and mentally focused.[26] Fluorescent lights with timers have been sent down to keep the men on a normal schedule by imitating day and night.[28] The miners affirmed their capability to participate in rescue efforts, saying "There are a large number of professionals who are going to help in the rescue efforts from down here."[30] Psychologists believe the miners having a role in their own destiny is important for maintaining motivation and optimism.[30] They divided themselves into three groups, one being responsible for the palomas, a second in charge of security and preventing further rock falls, and a third focusing on health.[30] Luis Urzúa became the overall leader and the oldest miner, Mario Gómez, was chosen for spiritual guidance.[30] Psychiatrists have supported that this hierarchical structure that preserves order and routine within the group of trapped miners is crucial to their mental health.[31]

It was determined that Johny Barrios was the most qualified of the miners to administer medicine and communicate on health issues due to his previous medical training.[32] Barrios vaccinated the group against tetanus and diphtheria.[15] Many of the miners developed severe skin problems due to the hot and wet conditions.[15] They were sent quick-drying clothing and small mats so they do not have to sleep directly on the ground.[15] In September, they received medical survival kits, including tourniquets, IV kits, and splints, as well as first aid training by videoconferencing.[33]

Health Minister Jaime Mañalich stated, "The situation is very similar to the one experienced by astronauts who spend months on end in the space station."[34] On 31 August, a team from NASA in the United States arrived in Chile to provide assistance. The team includes two physicians, one psychologist, and an engineer.[35]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Rescue plans

The Strata 950 raise borer drilling rig was the first to be used to drill the escape borehole.[36] First, a small pilot hole is drilled, then a larger drill bit widens the hole. The fine rock debris, known as cuttings, will fall down the pilot hole. An estimated 500 kg of rocks will fall down every hour.[32] Working in shifts 24 hours a day, the miners will have to keep the passage clear with industrial-sized battery-powered sweepers and wheel barrows at their disposal.[15] The miners will have to remove by themselves a total mass of drilling cuttings estimated between 700 and 1500 metric tonnes, considering a borehole diameter of 70 cm or 100 cm respectively, with a depth of 688 m and a rock density of 2.7 tonnes per cubic metre.

The diameter of the rescue borehole will be 66 cm (26 inches), meaning each miner will have to have a waistline of no more than 90 cm (35 inches) to escape.[8] In order to ensure they are the correct size an exercise regimen is being developed to keep them in shape.[29] The men will be extracted in a steel rescue capsule 54 cm in diameter (21 inches).[37] The capsule will have an oxygen supply, lighting, video link, reinforced roof to protect against rock falls, and an escape hatch with safety device to allow the miner to lower himself back down if the capsule becomes stuck.[37] Chilean Mining Minister Laurence Golborne told reporters at the mine that the rescuers estimated it would take about an hour to bring each miner to the surface and thus he expected the lifting phase of the rescue operation to take up to 48 hours.[38]

As of 18 September, while Chile was celebrating its Bicentennial, there were three plans in operation—the Strata 950 ("Plan A", 702 metre target depth at 90°), the Schramm T130XD ("Plan B", 638 metre target depth at 82°), and a RIG-422 drill ("Plan C", 597 meter target depth at 85°).[39][40] The installation of the RIG-422 was not complete at the time that the Schramm T130XD broke through.

The widened shaft being drilled by the Schramm T130XD reached the trapped miners at 8:05 a.m. early on 9 October,[41] after a 10 hour stoppage to change the drill-bit. As of 8 October the Strata 950 had reached 598 metres deep (قالب:%, still drilling its pilot hole). The RIG-422, the only machine which drills a shaft wide enough immediately, reached 372 metres (قالب:%).[42]

Several custom-built rescue pods, designed by NASA engineers and constructed by the Chilean Navy, were delivered to the site of the accident.[43] One was unveiled to the media, and some of the trapped miners' relatives were allowed to get inside the pod.

Jaime Mañalich, Minister of Health of the Republic of Chile, announced the miner rescue operation would begin on 12 October. Mañalich also indicated he expected only the first 100–200 metres of the shaft to be encased, a task that could be performed in only 10 hours.[44] On 9 October it was decided that only the top 96 metres of the shaft would be encased with steel pipes, but eventually only the first 56 metres were deemed to require encasing. This stage of the operation will likely be completed in 36 hours. Then a system with a winch and pulleys needs to be assembled, which will take another 48 hours. If everything goes as planned, the evacuation will proceed on 13 October.[45]

الانقاذ

| أحداث هذه المقالة هي أحداث جارية. المعلومات المذكورة قد تتغير بسرعة مع تغير الحدث. |

| العامل | Age[46] | وقت الانقاذ (CLDT)[47][48] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Florencio Ávalos | 31 | 13 اكتوبر 00:10 |

| 2. | Mario Sepúlveda | 40 | 13 اكتوبر 01:10 |

| 3. | Juan Illanes | 52 | 13 اكتوبر 02:07 |

| 4. | كارلوس ماماني | 23 | 13 اكتوبر 03:11 |

| 5. | Jimmy Sánchez | 19 | 13 اكتوبر 04:11 |

| 6. | Osmán Araya | 30 | 13 اكتوبر 05:35 |

| 7. | خوسيه اوجيدا | 46 | 13 اكتوبر 06:22 |

| 8. | Claudio Yáñez | 34 | 13 اكتوبر 07:04 |

| 9. | ماريو گوميس | 63 | 13 اكتوبر 08:00 |

| 10. | ألكس ڤيگا | 31 | 13 اكتوبر 08:53 |

| 11. | Jorge Galleguillos | 56 | 13 اكتوبر 09:31 |

| 12. | Edison Peña | 34 | 13 اكتوبر 10:13 |

| 13. | Carlos Barrios | 27 | 13 اكتوبر 10:55 |

| 14. | Víctor Zamora | 33 | 13 اكتوبر 11:32 |

| 15. | Víctor Segovia | 48 | 13 اكتوبر 12:08 |

| 16. | ادنيال هيرارا | 27 | 13 اكتوبر 12:50 |

| 17. | Omar Reygadas | 56 | 13 اكتوبر 13:39 |

| 18. | Esteban Rojas | 44 | 13 اكتوبر 14:49 |

| 19. | Pablo Rojas | 45 | 13 October 15:28 |

| 20. | Darío Segovia | 48 | 13 اكتوبر 15:59 |

| 21. | Yonni Barrios | 52 | 13 اكتوبر 16:31 |

| 22. | Samuel Ávalos | 43 | 13 اكتوبر 17:04 |

| 23. | Carlos Bugueño | 27 | 13 اكتوبر 17:33 |

| 24. | José Henríquez | 54 | 13 اكتوبر 17:59 |

| 25. | Renán Ávalos | 29 | 13 اكتوبر 18:24 |

| 26. | Claudio Acuña | 44 | |

| 27. | Franklin Lobos | 53 | |

| 28. | Richard Villarroel | 27 | |

| 29. | Juan Carlos Aguilar | 49 | |

| 30. | Raúl Bustos | 40 | |

| 31. | Pedro Cortéz | 24 | |

| 32. | Ariel Ticona | 29 | |

| 33. | Luis Urzúa | 54 |

| عمال تم انقاذهم | السن | وقت الانقاذ (CLDT) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Manuel González[49] | 32 | |

| 2. | Roberto Ríos[50] | 37 | |

| 3. | Patricio Robledo[50] | 39 | |

| 4. | Jorge Bustamante[50] | ||

| 5. | Patricio Sepúlveda[50] |

ردود الفعل

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت Navarrete, Camila (6 August 2010). "Se confirman las identidades de mineros atrapados en mina San José en Región de Atacama" (in Spanish). Radio Bío Bío. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ أ ب "Onemi confirma a 33 mineros atrapados en yacimiento en Atacama" (in Spanish). La Tercera. 6 August 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Illiano, Cesar (9 October 2010). "Rescue near for Chile miners trapped for 2 months". Reuters AlertNet. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Haroon Siddique (23 August 2010). "Chilean miners found alive – but rescue will take four months". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ "Chile Miners Rescue: Live". Telegraph. 12 October 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ أ ب Vila, Narayan (7 August 2010). "Amplio despliegue para rescatar a mineros atrapados". La Nación (Chile). Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ Estos son los mineros chilenos atrapados El Espectador, 24 August 2010

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Franklin, Jonathan (25 August 2010). "Chilean miners' families pitch up at Camp Hope". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Soto, Alonso (24 August 2010). "Chile sets sight on escape shaft for trapped miners". Reuters. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةfamiliessue - ^ "Ministro Golborne: El acceso por la chimenea ya no es una opción" (in Spanish). Radio Cooperativa (Chile). 7 August 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Piñera vuelve a Chile y viajará a zona del accidente en la mina San José" (in Spanish). La Tercera. 7 August 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Soto, Alonso (23 August 2010). "Chile secures lifeline to trapped miners, sends aid". Reuters. Yahoo News. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Sherwell, Philip (28 August 2010). "Camp Hope families wait in Chile's Atacama Desert for trapped miners". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Prengaman, Peter (29 August 2010). "Chile miners must move tons of rocks in own rescue". The Associated Press. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ "Timeline: Trapped Chilean miners". Reuters. 22 August 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ "Chile: Sonda llega cerca de mineros atrapados" (in Spanish). La Voz. 22 August 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ McMurtrie, Craig (24 August 2010). "Aussie drill expert called to Chile mine rescue". ABC News (Australia). Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ "Trapped Chile miners alive but long rescue ahead". NewsDaily. 23 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Miners trapped in Chile mine for 17 days 'are alive'". BBC News. 22 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت "Trapped Chile miners receive food and water". BBC News. 23 August 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت Soto, Alonso (24 August 2010). "Chile secures lifeline to trapped miners, sends aid". Reuters. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ أ ب "2nd bore hole reaches 33 trapped in Chile mine". Associated Press. 24 August 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: Text "Quilodran, Federico" ignored (help) - ^ "Trapped Chile miners give video tour of confinement". BBC News. 27 August 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "CMineros confirman que están en perfecto estado de salud tras contacto por citófono" (in Spanish). Radio BioBio. 23 August 2010. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث "Chile miners face four-month wait for rescue". MSNBC. Associated Press. 23 August 2010. Archived from the original on 24 August 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Hough, Andrew and Damien McElroy (24 August 2010). "Trapped Chile miners survived 18 days underground on pieces of tuna and milk". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت Franklin, Jonathan (27 August 2010). "NASA helping in historic rescue of trapped Chilean miners". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ أ ب "Chile's trapped miners told rescue could take months". BBC News. 25 August 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Laing, Aislinn and Nick Allen (27 August 2010). "Chile miners give video tour of cave". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Fritschy, Margot «Il est primordial que les mineurs gardent un espoir de sortie» Le Temps (Switzerland), 24 August 2010; Retrieved 24 August 2010

- ^ أ ب Franklin, Jonathan (26 August 2010). "Trapped Chilean miners face long shifts to keep their refuge clear of debris". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Hough, Andrew (9 September 2010). "Chilean miners' new medical 'survival kits' used by British troops". The Telegraph. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- ^ "Get us out of underground 'hell,' Chile miners plead". Associated Free Press. 25 August 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ "NASA Provides Assistance to Trapped Chilean Miners". NASA. 1 September 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ Brown, Adrian (26 August 2010). "Rescuers face tough challenge to save Chile miners". BBC News. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ أ ب Govan, Fiona (14 September 2010). "Chile miners: engineers unveil 21ins wide rescue capsule". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Chile awaits start of mine rescue". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 12 October 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ Page 5, San José Mine Rescue Operation presentation, Ministry of Mining, Republic of Chile

- ^ The Schramm T130XD air core drill was operated by a crew from Center Rock Drilling, Inc., of Berlin, Pennsylvania, under personal supervision of company president Brandon Fisher. Center Rock built the drills used on the TX130. While the Schramm rig, built by privately held Schramm, Inc. of West Chester, Pennsylvania, was already on the ground in Chile at the time of the mine collapse, additional drilling equipment was flown at no cost from the United States to Chile by United Parcel Service aboard an air freighter

- ^ La perforadora llegó al refugio donde se encuentran los mineros, La Nación On-Line, 9 October 2010

- ^ "Estado del operativo de rescate (Daily press release)". Ministry of Mining, Republic of Chile. 8 October 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Parker, Laura. "To Design Miners' Escape Pod, NASA Thought Small". AOL News. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "El histórico rescate de los mineros arrancará el martes próximo". La Nación On-Line. 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Evacuation of Chile miners 'likely to start Wednesday'". BBC News. 10 October 2010. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Profiles of Chile's trapped miners BBC News, 7 اكتوبر 2010.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةCNNBreaking - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةTelegraphLive - ^ Rescuer reaches trapped men in Chile mine Yahoo! News, 12 October 2010.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Minuto a minuto: Mineros arriban al hospital de Copiapó y "Fénix II" reinicia labores Emol Chile, 13 October 2010.

وصلات خارجية

- List of trapped miners, El Mercurio

- Help Site for the 33 Chilean Miners Facebook

- قالب:Pdflink Equipment used for rescue

- Miners in Chile trapped underground in the San Jose gold and copper mine in Copiapo Telegraph

- Rescue capsule diagrams: side view, opened; top view, cross-section; side view, occupied