عرق قوقازي

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Effective_protection_level على السطر 63: attempt to index field 'TitleBlacklist' (a nil value).

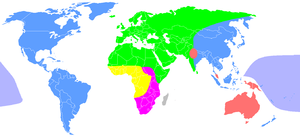

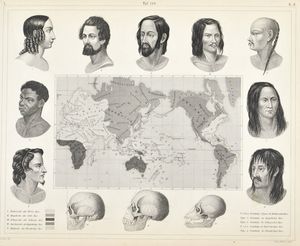

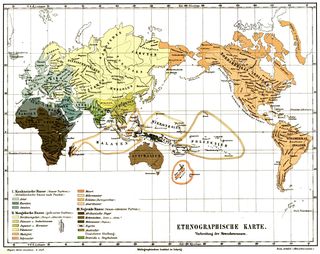

العرق القوقازي Caucasian race (أيضاً Caucasoid[1] أو Europid)[2] هي مجموعة من البشر كان ينظر إليهم تاريخياً على أنهم أصنوفة حيوية، التي، تبعاً للتصنيف العرقي التاريخي المستخدم، كانت تتضمن بعض أو جميع السكان القدماء والمعاصرين في أوروپا، غرب آسيا، آسيا الوسطى، جنوب آسيا، شمال أفريقيا، والقرن الأفريقي.[3]

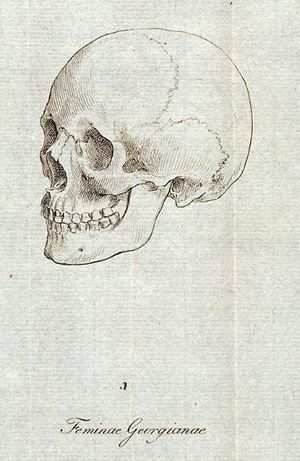

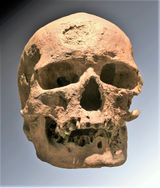

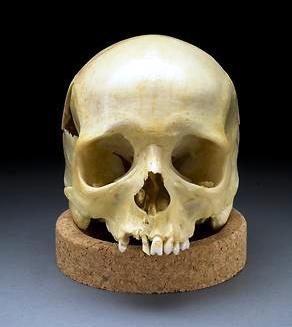

طُرح المصطلح لأول مرة في ثمانينيات القرن الثامن عشر بواسطة أعضاء مدرسة گوتينگن التاريخية،[4] ويشير المصطلح إلى واحد من ثلاثة أجناس رئيسية مزعومة للبشرية (القوقازي، المنغولي، الزنجي).[5] في علم الإنسان الحيوي، يستخدم مصطلح القوقازي كمصطلح عام للإشارة إلى الجماعات ذات النمط الظاهري المتشابه من هذه المناطق المختلفة، مع التركيز على تشريح الهيكل العظمي، وخاصة مورفولوجيا الجمجمة، ولون البشرة.[6] ومن ثم، فقد ثبت أن التجمعات "القوقازية" القديمة والحديثة تدرجت بشرتها بين اللون الأبيض والأسمر الداكن.[7] منذ النصف الثاني من القرن 20، انتقل علماء الأنثروپولوجيا الفيزيائية من الفهم النوعي للتنوع الحيوي البشري نحو منظور الجينوم والسكان، وإلى الميل نحو فهم "العرق" كتصنيف اجتماعي للبشر على أساس النمط الظاهري والنسب وكذلك العوامل الثقافية، كما يستخدم المفهوم في العلوم الاجتماعية.[8] على الرغم من أن مصطلح العرق القوقازي ونظيري الزننجي والمنغولي تستخدم بشكل أقل كتصنيف حيوي في علم إنسان الطب الشرعي (حيث تستخدم أحياناً كطريقة لتحديد النسب من رفات الإنسان بناء على تفسيرات القياسات العظمية)، لا تزال هذه المصطلحات المستخدمة من قبل بعض علماء الإنسان.[9]

في الولايات المتحدة، عادة ما يستخدم مصطلح القوقازي في سياق اجتماعي مختلف، كمرادف للأصل "الأبيض أو "الأوروپي".[10][11] استخدام هذا المصطلح في الإنگليزية الأمريكية منتقداً.[12]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

تاريخ المفهوم

ماينرز

لومنباخ

كون

| العرق القوقازي | |

| العرق الزنجي | |

| Capoid race | |

| العرق المنغولي | |

| Australoid race |

علم الإنسان العرقي

التصنيف

لوصف الأعراق البشرية

| القوقازي: الزنجي: غير مؤكد: | المنغولي: |

الأعراق الفرعية

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الأصول

الاستخدام في الولايات المتحدة

انظر أيضاً

- قياسات بشرية

- Dené–Caucasian languages – تشمل عائلات اللغات الصينية-التبتية، القوقازية الشمالية، النا-دني، الينسيانية، الڤاسكونية (تشمل الباسكية)، البوروشاسكية.

- المفاهيم العرقية التاريخية

- Leucism

- أشخاص من القوقاز

- الأعراق والعرقية في الولايات المتحدة

- العرقية وعلم الوراثة

المصادر

الهوامش

- ^ The traditional anthropological term Caucasoid is a conflation of the demonym Caucasian and the Greek suffix eidos (meaning "form", "shape", "resemblance"), implying a resemblance to the native inhabitants of the Caucasus. It etymologically contrasts with the terms Negroid, Mongoloid and Australoid (Freedman, B. J. (1984). "For debate... Caucasian" (PDF). British Medical Journal. Routledge. 288 (6418): 696–98. doi:10.1136/bmj.288.6418.696. PMC 1444385. PMID 6421437. Retrieved 27 March 2017.) For a contrast with the "Mongolic" or Mongoloid race, see footnote #4 pp. 58–59 in Beckwith, Christopher. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2. OCLC 800915872.

- ^ Pearson, Roger (1985). Anthropological glossary. R.E. Krieger Pub. Co. p. 79. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ Coon, Carleton Stevens (1939). The Races of Europe. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 400–01.

This third racial zone stretches from Spain across the Straits of Gibraltar to Morocco, and thence along the southern Mediterranean shores into Arabia, East Africa, Mesopotamia, and the Persian highlands; and across Afghanistan into India [...] The Mediterranean racial zone stretches unbroken from Spain across the Straits of Gibraltar to Morocco, and thence eastward to India[...] A branch of it extends far southward on both sides of the Red Sea into southern Arabia, the Ethiopian highlands, and the Horn of Africa.

- ^

- Baum 2006, pp. 84–85: "Finally, Christoph Meiners (1747–1810), the University of Göttingen “popular philosopher” and historian, first gave the term Caucasian racial meaning in his Grundriss der Geschichte der Menschheit (Outline of the History of Humanity, 1785)… Meiners pursued this “Göttingen program” of inquiry in extensive historical-anthropological writings, which included two editions of his Outline of the History of Humanity and numerous articles in Göttingisches Historisches Magazin"

- William R. Woodward (9 June 2015). Hermann Lotze: An Intellectual Biography. Cambridge University Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-316-29785-8.

...the five human races identified by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach – Negroes, American Indians, Malaysians, Mongolians, and Caucasians. He chose to rely on Blumenbach, leader of the Göttingen school of comparative anatomy

; also at [1] - Nicolaas A. Rupke (2002). Göttingen and the Development of the Natural Sciences. Wallstein-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89244-611-8.

For it was at Gottingen in this period that the outlines of a system of classification were laid down in a manner that still shapes the way in which we attempt to comprehend the different varieties of humankind — including usage of such terms as "Caucasian".

- Charles Simon-Aaron (2008). The Atlantic Slave Trade: Empire, Enlightenment, and the Cult of the Unthinking Negro. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-5197-1.

Here, Blumenbach placed the white European at the apex of the human family; he even gave the European a new name — i.e., Caucasian. This relationship also inspired the academic labors of Karl Otfried Muller, C. Meiners and K.A. Heumann, the more important thinkers at Gottingen for our project. (This list is not intended to be exhaustive).

- RACAR, Revue D'art Canadienne: Canadian Art Review. Society for the Promotion of Art History Publications in Canada. 2004.

It is in the context of the shift to the human as both subject and object that Foucault has placed the "invention" of the human sciences, and it is also in this context that the various human histories as conceived and taught at Gottingen — from the theories of race proposed by Christoph Meiners and Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (who would coin the word "Caucasian" in the 1790s) to new theories of history as interpreted by Johann Christoph Gatterer and August Ludwig von Schlozer to a new art history as conceived by Fiorillo — can be considered.

- ^ Pickering, Robert (2009). The Use of Forensic Anthropology. CRC Press. p. 82. ISBN 1-4200-6877-6.

- ^ Pickering, Robert (2009). The Use of Forensic Anthropology. CRC Press. p. 109. ISBN 1-4200-6877-6.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBlumenbach - ^ Caspari, Rachel (2003). "From types to populations: A century of race, physical anthropology, and the American Anthropological Association" (PDF). American Anthropologist. 105 (1): 65–76. doi:10.1525/aa.2003.105.1.65.

- ^ See these sources:

- Ousley, S.; Jantz, R.; Freid, D. (2009). "Understanding race and human variation: why forensic anthropologists are good at identifying race". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 139 (1): 68–76. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21006.

Although a shift in terminology has been underway in forensic anthropology, with ancestry used more often in place of race, in many case reports the classic physical anthropology terms such as Caucasoid, Mongoloid, or Negroid are still seen

- Sue Black; Eilidh Ferguson (19 April 2016). Forensic Anthropology: 2000 to 2010. CRC Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-1-4398-4589-9.

Semantically speaking, the term race appears to pertain to the individual and has largely been succeeded in physical anthropology by the more impersonal term ancestry. The distinction between these terms is considered to be important. Race may be regarded as a "socially constructed mechanism for self identification and group membership" and so biologically meaningless, whereas ancestry is a "scientifically derived descriptor of the biological component of population variation" (Konigsberg et al. 2009: 77–78). So, why do the rather politically sensitive terms Caucasoid, Mongoloid, or Negroid still appear in published literature (Ousley et al. 2009)? There are considered to be four basic ancestry groups into which an individual can be placed by physical appearance, not accounting for admixture: the sub-Saharan African group ("Negroid"), the European group ("Caucasoid"), the Central Asian group ("Mongoloid"), and the Australasian group ("Australoid"). The rather outdated names of all but one of these groups were originally derived from geography: The Caucasoid group traversed the Caucasus Mountains as they spread into Europe and eastern Asia. Since the majority of native peoples from the Indian subcontinent, northern and northeastern Africa and the Near East fall into this group, to say that the group is of "European" ancestry does not really suffice. Plus, the terms Caucasoid or Caucasian do not have the same oppressive, persecutory connotations as the other terms and so are less likely to cause offense.

- Robert B. Pickering; David Bachman (22 January 2009). The Use of Forensic Anthropology. CRC Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-1-4200-6878-8.

Race is both a cultural and a biological term. For more than a century, scientists and philosophers have tried to define race and describe races. Some scientists define only three races: caucasoid, mongoloid, and negroid, while other scientists have defined more than 10. In our current climate of multicultural sensitivity, some scholars, not forensic anthropologists, suggest that race does not exist, or at least it should not be talked about....From the forensic perspective, using the "three-race" model still has some value in describing broad genetic and morphological characteristics. This model is used by many people to describe themselves and others. Therefore, it falls to the forensic investigator to use the term defined by the model in trying to identify the dead. The model is not perfect, but it does help us understand some of the variation in shape and form on some parts of the skeleton, particularly the skull.

- Pekka Saukko; Bernard Knight (4 November 2015). Knight's Forensic Pathology Fourth Edition. CRC Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-4441-6508-1.

There is no consensus as to whether forensic anthropologists or osteologists should include assesments of 'race' or ancestry in skeletal reports as according to Iscan and Steyn it seems to remain tentative at best.111 As of the osteological range present little difficulty, as Brothwell usual, those at the extreme ends remarks ... usual warnings about dogmatic opinions are even more important in this field.... There are three main racial groups: Caucasian, Mongoloid and Negroid.

- Ousley, S.; Jantz, R.; Freid, D. (2009). "Understanding race and human variation: why forensic anthropologists are good at identifying race". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 139 (1): 68–76. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21006.

- ^ Bhopal, R.; Donaldson, L. (1998). "White, European, Western, Caucasian, or what? Inappropriate labeling in research on race, ethnicity, and health". American Journal of Public Health. 88 (9): 1303–1307. doi:10.2105/ajph.88.9.1303. PMC 1509085.

- ^ Baum 2006, p. 3,18.

- ^ See for example:

- Herbst, Philip (15 June 1997). The color of words: an encyclopaedic dictionary of ethnic bias in the United States. Intercultural Press. ISBN 978-1-877864-97-1.

Though discredited as an anthropological term and not recommended in most editorial guidelines, it is still heard and used, for example, as a category on forms asking for ethnic identification. It is also still used for police blotters (the abbreviated Cauc may be heard among police) and appears elsewhere as a euphemism. Its synonym, Caucasoid, also once used in anthropology but now dated and considered pejorative, is disappearing.

- Mukhopadhyay, Carol C. (30 June 2008). "Getting Rid of the Word "Caucasian"". In Mica Pollock (ed.). Everyday Antiracism: Getting Real About Race in School. New Press. pp. 14–. ISBN 978-1-59558-567-7.

Yet there is one striking exception in our modem racial vocabulary: the term "Caucasian." Despite being a remnant of a discredited theory of racial classification, the term has persisted into the twenty-first century, within as well as outside of the educational community. It is high time we got rid of the word Caucasian. Some might protest that it is "only a label." But language is one of the most systematic, subtle, and significant vehicles for transmitting racial ideology. Terms that describe imagined groups, such as Caucasian, encapsulate those beliefs. Every time we use them and uncritically expose students to them, we are reinforcing rather than dismantling the old racialized worldview. Using the word Caucasian invokes scientific racism, the false idea that races are naturally occurring, biologically ranked subdivisions of the human species and that Caucasians are the superior race. Beyond this, the label Caucasian can even convey messages about which groups have culture and are entitled to recognition as Americans.

- Dewanjuly, Shaila (2013-07-06). "Has 'Caucasian' Lost Its Meaning?". New York Times. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

AS a racial classification, the term Caucasian has many flaws, dating as it does from a time when the study of race was based on skull measurements and travel diaries… Its equivalents from that era are obsolete — nobody refers to Asians as "Mongolian" or blacks as "Negroid."… There is no legal reason to use it. It rarely appears in federal statutes, and the Census Bureau has never put a checkbox by the word Caucasian. (White is an option.)… The Supreme Court, which can be more colloquial, has used the term in only 64 cases, including a pair from the 1920s that reveal its limitations… In 1889, the editors of the original Oxford English Dictionary noted that the term Caucasian had been "practically discarded." But they spoke too soon. Blumenbach's authority had given the word a pseudoscientific sheen that preserved its appeal. Even now, the word gives discussions of race a weird technocratic gravitas, as when the police insist that you step out of your "vehicle" instead of your car…. Susan Glisson, who as the executive director of the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation in Oxford, Miss., regularly witnesses Southerners sorting through their racial vocabulary, said she rarely hears "Caucasian." "Most of the folks who work in this field know that it's a completely ridiculous term to assign to whites," she said. "I think it's a term of last resort for people who are really uncomfortable talking about race. They use the term that's going to make them be as distant from it as possible."

- Herbst, Philip (15 June 1997). The color of words: an encyclopaedic dictionary of ethnic bias in the United States. Intercultural Press. ISBN 978-1-877864-97-1.

المراجع

- Camberg, Kim (December 13, 2005). "Long-term tensions behind Sydney riots". BBC News. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Leroi, Armand Marie (March 14, 2005). "A Family Tree in Every Gene". The New York Times. p. A23.

- Lewontin, Richard (2005). "Confusions About Human Races". Race and Genomics, Social Sciences Research Council. Retrieved December 28, 2006.

- Painter, Nell Irvin (2003). "Collective Degradation: Slavery and the Construction of Race. Why White People are Called Caucasian" (PDF). Yale University. Archived from the original (PDF) on أكتوبر 20, 2013. Retrieved أكتوبر 9, 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Risch N, Burchard E, Ziv E, & Tang H (July 2002). "Categorization of humans in biomedical research: genes, race and disease". Genome Biol. 3 (7): comment2007.2001–12. doi:10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-comment2007. PMC 139378. PMID 12184798.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Rosenberg NA; Pritchard JK; Weber JL; et al. (December 2002). "Genetic structure of human populations". Science. 298 (5602): 2381–85. Bibcode:2002Sci...298.2381R. doi:10.1126/science.1078311. PMID 12493913.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Rosenberg NA, Mahajan S, Ramachandran S, Zhao C, Pritchard JK, & Feldman MW (December 2005). "Clines, Clusters, and the Effect of Study Design on the Inference of Human Population Structure". PLoS Genet. 1 (6): e70. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0010070. PMC 1310579. PMID 16355252.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Templeton, Alan R. (September 1998). "Human races: A genetic and evolutionary perspective". American Anthropologist. 100 (3): 632–50. doi:10.1525/aa.1998.100.3.632. JSTOR 682042.

- أعمال أدبية

- Augstein, HF (1999). "From the Land of the Bible to the Caucasus and Beyond". In Harris, Bernard; Ernst, Waltraud (eds.). Race, Science and Medicine, 1700–1960. New York: Routledge. pp. 58–79. ISBN 0-415-18152-6.

- Baum, Bruce (2006). The rise and fall of the Caucasian race: a political history of racial identity. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-9892-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blumenbach, Johann Friedrich (1775) On the Natural Varieties of Mankind – the book that introduced the concept

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca (2000). Genes, Peoples and Languages. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9486-X.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1981). The Mismeasure of Man. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-01489-4. – a history of the pseudoscience of race, skull measurements, and IQ inheritabilit

- Guthrie, Paul (1999). The Making of the Whiteman: From the Original Man to the Whiteman. Chicago: Research Associates School Times. ISBN 0-948390-49-2.

- Piazza, Alberto; Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca; Menozzi, Paolo (1996). The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02905-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) – a major reference of modern population genetics - Stoddard, Theodore Lothrop (1924). Racial Realities in Europe. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Wolf, Eric R.; Cole, John N. (1999). The Hidden Frontier: Ecology and Ethnicity in an Alpine Valley. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21681-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)