تزاوج البشر القدماء مع البشر المعاصرين

تزاوج البشر القدماء مع البشر المعاصرين يُعتقد أنه حدث بين modern humans and Neanderthals, Denisovans, as well as other archaic humans over the course of the Middle Paleolithic.

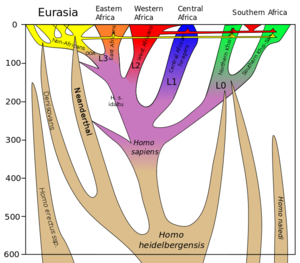

Neanderthal-derived DNA accounts for an estimated 1–4% of the genome of modern Eurasian populations, but it is significantly absent or uncommon in the genome of most groups in Sub-Saharan Africa. Some researchers have suggested that the observed data might alternatively be explained by ancient subpopulation structure. In modern Oceanian and Southeast Asian populations, there is a relative increase of Denisovan-derived DNA (an estimated 4–6% of the Melanesian genome is derived from Denisovans). In certain modern populations in Africa, there is also evidence for archaic admixture with as yet unidentified hominins.

نياندرتال

الوراثة

−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||

نسب الاختلاط

Through whole-genome sequencing of three Vindija Neanderthals, a draft sequence of the Neanderthal genome was published by a team of researchers led by Richard Green on 7 May 2010 in the journal Science and revealed that Neanderthals shared more alleles with Eurasian populations (e.g. French, Han Chinese, and Papua New Guinean) than with Sub-Saharan African populations (e.g. Yoruba and San).[2] According to Green et al. (2010), the observed excess of genetic similarity is best explained by recent gene flow from Neanderthals to modern humans after the migration out of Africa.[2] Green et al. (2010) estimated the proportion of Neanderthal-derived ancestry to be 1–4% of the Eurasian genome.[2] The proportion was estimated to be 1.5–2.1% in Prüfer et al. (2013),[3] but it was later revised to a higher 1.8–2.6% and it was noted that East Asians carry more Neandertal DNA (2.3–2.6%) than Western Eurasians (1.8–2.4%) in Prüfer et al. (2017).[4] Lohse and Frantz (2014) infer an even higher rate of 3.4–7.3%.[5]

Distance to lineages

Changes in modern humans

Population substructure theory

Morphology

Denisovans

Archaic African hominins

Rapid decay of fossils in Sub-Saharan African environments makes it currently unfeasible to compare modern human admixture with reference samples of archaic Sub-Saharan African hominins.[8]

Indirect evidence

Human papillomavirus type 58 causes cervical cancer in 10–20% of cases in East Asia. It is rarely found elsewhere. An estimate of the date of evolution of the most recent common ancestor places it at 478,600 years ago (95% HPD 391,000–569,600).[9] As this date is before the generally accepted date of the evolution of modern humans, this suggests that this virus was transmitted to humans from a now extinct hominin. As this virus is usually transmitted sexually this furthermore suggests that mating occurred in this area between modern humans and a now extinct hominin species.[9]

See also

== المراجع ==

- ^ based on Schlebusch et al., "Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago" Science, 28 Sep 2017, DOI: 10.1126/science.aao6266, Fig. 3 (H. sapiens divergence times) and Stringer, C. (2012). "What makes a modern human". Nature. 485 (7396): 33–35. Bibcode:2012Natur.485...33S. doi:10.1038/485033a. PMID 22552077. (archaic admixture).

- ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةgreends - ^ Prüfer, K.; Racimo, F.; Patterson, N.; Jay, F.; Sankararaman, S.; Sawyer, S.; et al. (2014) [Online 2013]. "The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains". Nature. 505 (7481): 43–49. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...43P. doi:10.1038/nature12886. PMC 4031459. PMID 24352235.

- ^ Prüfer, K.; de Filippo, C.; Grote, S.; Mafessoni, F.; Korlević, P.; Hajdinjak, M.; et al. (2017). "A high-coverage Neandertal genome from Vindija Cave in Croatia". Science. 358: 655–658. doi:10.1126/science.aao1887.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةlohfra14 - ^ "Oase 2". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةmeyer12highcov - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةlac12adaafr - ^ أ ب Chen, Z.; Ho, W.C.S.; Boon, S.S.; Law, P.T.Y.; Chan, M.C.W.; DeSalle, R; et al. (2017). "Ancient Evolution and Dispersion of Human Papillomavirus Type 58 Variants". Journal of Virology. 91: JVI.01285-17. doi:10.1128/JVI.01285-17.