المملكة الهندو-يونانية

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| قالب:Indo-Greeks | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| قالب:Indo-Greek articles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

الممالك الهندو-يونانية كانت ممالك هيلينية جزئياً تغطي أجزاء مختلفة من أفغانستان والمناطق الشمالية الغربية من شبه القارة الهندية (مناطق من پاكستان وشمال غرب الهند المعاصرة)،[1][2][3][4][5][6] أثناء القرنين الأخيرين قبل الميلاد وحكمها ما يزيد عن ثلاثين ملك. أوثيدموس الأول، حسب لپوليبيوس،[7] كان يونانياً ماگنتسياً. ابنه دمتريوس الأول، مؤسس المملكة الهندو-يونانية، كان بالتالي من عرقية يونانية على الأقل من جهة أبيه. كما عقدت معاهدة زواج لدمتريوس وابنة الحاكم السلوق أنطيوخس الثالث (الذي كان لديه بعض الأصول الفارسية).[8] عرقية الحكام الهندو-يونانيين اللاحقين كان أقل وضوحاً.[9] على سبيل المثال، أرتميدوروس (80 ق.م.) قد يكون من أصول هندية-سكثيونية.

تأسست المملكة عندما قام الملك البختيري-اليوناني دمتريوس بغزو شبه القارة الهندية في أوائل القرن الثاني ق.م. وفي النهاية انقسم اليونانييون في شبه القارة الهندية من البختيريين-اليونانيين المتمركزين في بختريا (على الحدود بين أفغانستان وأوزبكستان حالياً)، والهنود-اليونانيين في ما يعرف اليوم شمال غرب شبه القارة الهندية. من أشهر الحكام الهندو-يونانيين هو مناندر (ميليندا). كانت عاصمته في ساكالا في الپنجاب (سيالكوت حالياً).

يستخدم مصطلح "المملكة الهندو-يونانية" لوصف عدد من الأسر السياسية الحاكمة، والتي عادة ما ارتبطت بعدد من العواصم المحلية مثل تاكسيلا،[10] (الپنجاب (پاكستان) حالياً)، پوشكالاڤاتي وساگالا.[11]

في أعقاب وفاة مناندار، انقسمت معظم امبراطوريته وتراجع النفوذ الهندو-يوناني بشكل كبير. الكثير من الممالك الجديدة والجمهورية في شرق نهر راڤي بدأت في صك عملات معدنية جديدة تصور الانتصارات العسكرية.[12] من أشهر الكيانات السياسية التي تشكلت جمهورية يودهياس، أرجوناياناس، وأودومباراس. يقال أن يودهياس وأرجوناياناس حازتا "النصر عن طريق السيف".[13] سرعان ما تعاقبت اسرة داتا واسرة ميتا على حكم ماثورا. وفي نهاية المطاف اختفى الهنود-اليونانييين ككيان سياسي حوالي عام 10 م في أعقاب غزوات الهنود السكثيون، بالرغم من بقاء جيوب من السكان اليونانيين لعدة قرون تحت الحكم الهندو-پارثي والكوشاني اللاحقين.[14]

خلفية

التواجد اليوناني الأولي في شبه القارة الهندية

الحكم اليوناني في بختريا

صعود الشونگا (185 ق.م.)

تاريخ المملكة الهندو-يونانية

طبيعة وجودة الموارد

توسع دمتريوس إلى الهند

أول نظام نقدي ثنائي اللغة

حكم مناندر الأول

| |

| Menander I became the most important of the Indo-Greek rulers.[19] | Eucratides I toppled the Greco-Bactrian Euthydemid dynasty, and attacked the Indo-Greeks from the west. |

حكم ماثورا

الممالك الهندو-يونانية بعد مناندر

التفاعلات بين الثقافة والديانات الهندية

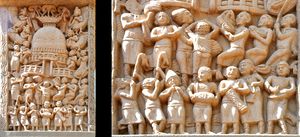

الهنود-اليونانييون في مناطق ڤيديشا وسانتشي (115 ق.م.)

| Early reliefs at Sanchi, Stupa No.2 (circa 115 BC) | |

Sanchi, Stupa No 2 Mason's marks in Kharoshti point to craftsmen from the north-west (region of Gandhara) for the earliest reliefs at Sanchi, circa 115 BC.[20][21][22] |

|

الهنود-اليونانيون وبارهوت (100-75 ق.م.)

سانتشي ياڤاناس (50-0 ق.م.)

الأفول

خسارة الأراضي الكوشية الهندية (70 ق.م.-)

خسارة الأراضي الوسطى (48/47 ق.م.)

خسارة الأراضي الشرقية (10 م)

الإسهامات اللاحقة

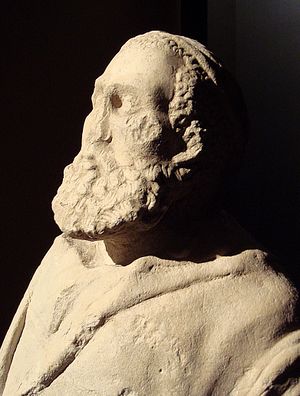

| The "Yavana cave", Cave No.17 of Pandavleni caves, near Nashik (2nd century AD) | |

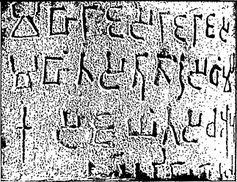

The "Yavana" inscription on the back wall of the veranda, Cave No.17, Nashik. Cave No.17 has one inscription, mentioning the gift of the cave by Indragnidatta the son of the Yavana (i.e. Greek or Indo-Greek) Dharmadeva:

| |

الأيديولوجيا

الدين

التفاعل مع البوذية

"أتباع دارما"

علامات الرحمة

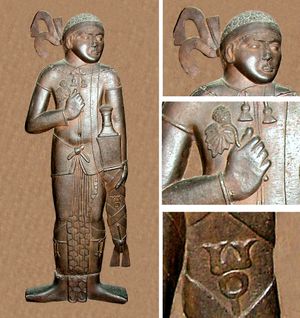

Philoxenus (c. 100 BC), unarmed, making a blessing gesture.

Nicias making a blessing gesture.

Strato I in combat gear, making a blessing gesture, circa 100 BCE.

عبادة باگاڤاتا

الفن

الاقتصاد

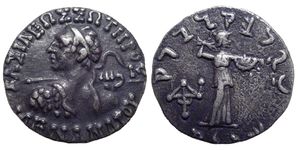

صك العملة

دفع الجزية

التجارة مع الصين

تجارة المحيط الهندي

القوات المسلحة

التكنولوجيا العسكرية

خجم الجيوش الهندو-يونانية

الذكرى الهندو-يونانية

قائمة الملوك الهندو-يونانيين

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

الهوامش

- ^ Jackson J. Spielvogel (14 September 2016). Western Civilization: Volume A: To 1500. Cengage Learning. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-305-95281-2.

The invasion of India by a Greco-Bactrian army in ... led to the creation of an Indo-Greek kingdom in northwestern India (present-day India and Pakistan).

- ^ Erik Zürcher (1962). Buddhism: its origin and spread in words, maps, and pictures. St Martin's Press. p. 45.

Three phases must be distinguished, (a) The Greek rulers of Bactria (the Oxus region) expand their power to the south, conquer Afghanistan and considerable parts of north-western India, and establish an Indo-Greek kingdom in the Panjab where they rule as 'kings of India'; i

- ^ Heidi Roupp (4 March 2015). Teaching World History: A Resource Book. Routledge. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-317-45893-7.

There were later Indo-Greek kingdoms in northwest India. ...

- ^ Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Psychology Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.

They are referred to as 'Indo-Greeks' and there were about forty such kings and rulers who controlled large areas of northwestern India and Afghanistan. Their history ...

- ^ Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Pratapaditya Pal (1986). Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 B.C.-A.D. 700. University of California Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-520-05991-7.

Since parts of their territories comprised northwestern India, these later rulers of Greek origin are generally referred to as Indo-Greeks.

- ^ Joan Aruz; Elisabetta Valtz Fino (2012). Afghanistan: Forging Civilizations Along the Silk Road. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-58839-452-1.

The existence of Greek kingdoms in Central Asia and northwestern India after Alexander's conquests had been known for a long time from a few fragmentary texts from Greek and Latin classical sources and from allusions in contemporary Chinese chronicles and later Indian texts.

- ^ 11.34

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةPolybius 11.34 - ^ ("Notes on Hellenism in Bactria and India". W. W. Tarn. Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 22 (1902), pp. 268–293).

- ^ Mortimer Wheeler Flames over Persepolis (London, 1968). Pp. 112 ff. It is unclear whether the Hellenistic street plan found by Sir John Marshall's excavations dates from the Indo-Greeks or from the Kushans, who would have encountered it in Bactria; Tarn (1951, pp. 137, 179) ascribes the initial move of Taxila to the hill of Sirkap to Demetrius I, but sees this as "not a Greek city but an Indian one"; not a polis or with a Hippodamian plan.

- ^ "Menander had his capital in Sagala" Bopearachchi, "Monnaies", p.83. McEvilley supports Tarn on both points, citing Woodcock: "Menander was a Bactrian Greek king of the Euthydemid dynasty. His capital (was) at Sagala (Sialkot) in the Punjab, "in the country of the Yonakas (Greeks)"." McEvilley, p.377. However, "Even if Sagala proves to be Sialkot, it does not seem to be Menander's capital for the Milindapanha states that Menander came down to Sagala to meet Nagasena, just as the Ganges flows to the sea."

- ^ "Most of the people east of the Ravi already noticed as within Menander's empire -Audumbaras, Trigartas, Kunindas, Yaudheyas, Arjunayanas- began to coins in the first century BC, which means that they had become independent kingdoms or republics.", Tarn, The Greeks in Bactria and India

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=-HeJS3nE9cAC&pg=PA324#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ "When the Greeks of Bactria and India lost their kingdom they were not all killed, nor did they return to Greece. They merged with the people of the area and worked for the new masters; contributing considerably to the culture and civilization in southern and central Asia." Narain, "The Indo-Greeks" 2003, p.278

- ^ "A minor rock edict, recently discovered at Kandahar, was inscribed in two scripts, Greek and Aramaic", India, the Ancient Past, Burjor Avari, p. 112

- ^ Jairazbhoy, Rafique Ali (1995). Foreign influence in ancient Indo-Pakistan. Sind Book House. p. 100. ISBN 969-8281-00-2.

Apollodotus, founder of the Graeco- Indian kingdom (c. 160 BC).

- ^ Senior, Indo-Scythian coins, p.xii

- ^ Reh Inscription Of Menander And The Indo-Greek Invasion Of The Ganga Valley, Sharma, G.R., 1980 p.ix-x, 10-11, Quote: "The archaeological evidence of unprecedented devastation of cities and towns from Delhi Hastinapur to Patna neatly corroborates (...)"

- ^ "Numismats and historians all consider that Menander was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, and the most illustrious of the Indo-Greek kings", Bopearachchi, "Monnaies", p.76

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةAG - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةShaw 90 - ^ Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, C. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD, Julia Shaw, Left Coast Press, 2013 p.88ff

- ^ An Indian Statuette From Pompeii, Mirella Levi D'Ancona, in Artibus Asiae, Vol. 13, No. 3 (1950) p.171

- ^ Faces of Power: Alexander's Image and Hellenistic Politics, Andrew Stewart, University of California Press, 1993 p.180

- ^ Popular Controversies in World History: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions [4 volumes]: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions, Steven L. Danver, ABC-CLIO, 2010 p.91

- ^ Buddhist Art & Antiquities of Himachal Pradesh, Up to 8th Century A.D., Omacanda Hāṇḍā, Indus Publishing, 1994 p.48

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBoardman 115 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةAC - ^ Epigraphia Indica Vol.18 p.328 Inscription No10

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةEI 90 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRT - ^ The coins of the Greek and Scythic kings of Bactria and India in the British Museum, p.50 and Pl. XII-7 [1]

- ^ Benjamin Rowland JR, foreword to "The Dyasntic art of the Kushan", John Rosenfield, 1967

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةNeedham 237 - ^ Tarn, p. 494.

- ^ O. Bopearachchi, "Monnaies gréco-bactriennes et indo-grecques, Catalogue raisonné", Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, 1991, p.453

- ^ History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE – 100 CE, Sonya Rhie Quintanilla, BRILL, 2007, p.9 [2]

أعمال مرجعية

- Avari, Burjor (2007). India: The ancient past. A history of the Indian sub-continent from c. 7000 BC to AD 1200. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-35616-4.

- Banerjee, Gauranga Nath (1961). Hellenism in ancient India. Delhi: Munshi Ram Manohar Lal. OCLC 1837954 ISBN 0-8364-2910-9.

- Bernard, Paul (1994). "The Greek Kingdoms of Central Asia." In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250, pp. 99–129. Harmatta, János, ed., 1994. Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 92-3-102846-4.

- Boardman, John (1994). The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03680-2.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (1991). Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné (in French). Bibliothèque Nationale de France. ISBN 2-7177-1825-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (1998). SNG 9. New York: American Numismatic Society. ISBN 0-89722-273-3.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (2003). De l'Indus à l'Oxus, Archéologie de l'Asie Centrale (in French). Lattes: Association imago-musée de Lattes. ISBN 2-9516679-2-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Bopearachchi, Osmund (1993). Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian coins in the Smithsonian Institution. Washington: National Numismatic Collection, Smithsonian Institution. OCLC 36240864.

- Bussagli, Mario; Francine Tissot; Béatrice Arnal (1996). L'art du Gandhara (in French). Paris: Librairie générale française. ISBN 2-253-13055-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Cambon, Pierre (2007). Afghanistan, les trésors retrouvés (in French). Musée Guimet. ISBN 978-2-7118-5218-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Errington, Elizabeth; Joe Cribb; Maggie Claringbull; Ancient India and Iran Trust; Fitzwilliam Museum (1992). The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Cambridge: Ancient India and Iran Trust. ISBN 0-9518399-1-8.

- Faccenna, Domenico (1980). Butkara I (Swāt, Pakistan) 1956–1962, Volume III 1. Rome: IsMEO (Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente).

- Foltz, Richard (2010). Religions of the Silk Road: premodern patterns of globalization. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1.

- Keown, Damien (2003). A Dictionary of Buddhism. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860560-9.

- Lowenstein, Tom (2002). The vision of the Buddha: Buddhism, the path to spiritual enlightenment. London: Duncan Baird. ISBN 1-903296-91-9.

- Marshall, Sir John Hubert (2000). The Buddhist art of Gandhara: the story of the early school, its birth, growth, and decline. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 81-215-0967-X.

- Marshall, John (1956). Taxila. An illustrated account of archaeological excavations carried out at Taxila (3 volumes). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

- McEvilley, Thomas (2002). The Shape of Ancient Thought. Comparative studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies. Allworth Press and the School of Visual Arts. ISBN 1-58115-203-5.

- Mitchiner, John E.; Garga (1986). The Yuga Purana: critically edited, with an English translation and a detailed introduction. Calcutta, India: Asiatic Society. OCLC 15211914 ISBN 81-7236-124-6.

- Narain, A.K. (1957). The Indo-Greeks. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- reprinted by Oxford, 1962, 1967, 1980; reissued (2003), "revised and supplemented", by B. R. Publishing Corporation, New Delhi.

- Narain, A.K. (1976). The coin types of the Indo-Greeks kings. Chicago, USA: Ares Publishing. ISBN 0-89005-109-7.

- Puri, Baij Nath (2000). Buddhism in Central Asia. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0372-8.

- Rosenfield, John M. (1967). The Dynastic Arts of the Kushans. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 81-215-0579-8.

- Salomon, Richard. "The "Avaca" Inscription and the Origin of the Vikrama Era". 102.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|quotes=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Seldeslachts, E. (2003). The end of the road for the Indo-Greeks?. (Also available online): Iranica Antica, Vol XXXIX, 2004.

{{cite book}}: External link in|location= - Senior, R. C. (2006). Indo-Scythian coins and history. Volume IV. Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. ISBN 0-9709268-6-3.

- Tarn, W. W. (1938). The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)- Second edition, with addenda and corrigenda, (1951). Reissued, with updating preface by Frank Lee Holt (1985), Ares Press, Chicago ISBN 0-89005-524-6

- Afghanistan, ancien carrefour entre l'est et l'ouest (in French and English). Belgium: Brepols. 2005. ISBN 2-503-51681-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - 東京国立博物館 (Tokyo Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan); 兵庫県立美術館 (Hyogo Kenritsu Bijutsukan) (2003). Alexander the Great: East-West cultural contacts from Greece to Japan. Tokyo: 東京国立博物館 (Tokyo Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan). OCLC 53886263.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Vassiliades, Demetrios (2000). The Greeks in India – A Survey in Philosophical Understanding. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt Limited. ISBN 81-215-0921-1.

وصلات خارجية

- Indo-Greek history and coins

- Ancient coinage of the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms

- Text of Prof. Nicholas Sims-Williams (University of London) mentioning the arrival of the Kushans and the replacement of Greek Language.

- Wargame reconstitution of Indo-Greek armies

- Files dealing with Indo-Greeks & a genealogy of the Bactrian kings

- The impact of Greco-Indian Culture on Western Civilisation

- Some new hypotheses on the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms by Antoine Simonin

- Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek Kingdoms in Ancient Texts

| أظهرالممالك الوسطى في الهند |

|---|

- Pages using infobox country with unknown parameters

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages with empty portal template

- CS1 maint: location

- هنود-يونانيون

- تاريخ آسيا الوسطى

- تاريخ الهند

- دويلات هيلينية

- جماعات عرقية في الهند

- شعوب قديمة في پاكستان

- تأسيسات عقد 180 ق.م.

- انحلالات عقد 10

- دول وأراضي تأسست في القرن الثاني ق.م.

- دول وأراضي انحلت في القرن الأول

- انحلالات القرن الأول

![Foreigner on a horse. The medallions are dated circa 115 BC.[21]](/w/images/thumb/e/e5/Sanchi_Stupa_2_man_on_horse.jpg/166px-Sanchi_Stupa_2_man_on_horse.jpg)

![Lakshmi with lotus and two child attendants, probably derived from similar images of Venus[23]](/w/images/thumb/6/66/Lakshmi_Sanchi_Stupa_2.jpg/180px-Lakshmi_Sanchi_Stupa_2.jpg)