الليدي هستر ستانهوپ

الليدي هستر لوسي ستانهوپ Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope (و. 12 مارس 1776 - 23 يونيو 1839) عميلة بريطانية في جبل لبنان، هي أكبر أنجال تشارلز ستانهوپ، إرل ستانهوپ الثالث، من زوجته الأولى الليدي هستر پت، يذكرها التاريخ بمغامراتها وأسفارها في العالم العربي ودورها الرئيسي في إضرام ثورة الدروز على حكم محمد علي.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

النشأة

يقول علي الوردي عالم الاجتماع العراقي في كتابه «لمحات اجتماعية من تاريخ العراق الحديث»: «لعل من المناسب هنا أن نذكر شيئا عن امرأة بريطانية كان لها دور لا يستهان به في اثارة الشوام على الحكم المصري هي الليدي هستر ستانهوب، وسيرة هذه المرأة لا تخلو من طرافة وشذوذ، فهي من ذوات الحسب والنسب، إذ كان خالها وليام پت، الأصغر رئيس الوزراء البريطاني، وجدها هو اللورد جاثام، ولكنها سئمت الحياة في بريطانيا بعد موت خالها في عام 1810، وقيل أنها اصيبت بخيبة في الحب، فآثرت السفر إلى الشرق الاوسط.

الحياة في الخارج

وجاء بصحبتها شاب غني كان عاشقا لها اسمه ميشيل مريون، فوصلت الى اسطنبول ثم انتقلت منها الى القاهرة واستقبلها الاعراب هناك كأنها ملكة، وكانت هي تسرف في العطاء وفي إحاطة نفسها بمظاهر الأبهة والبذخ، كأنها تريد ان تعيد إلى الأذهان اسم زنوبيا ملكة تدمر.[1]

الرحلة إلى الشرق الأدنى والأوسط

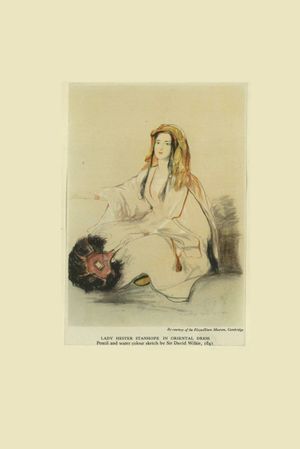

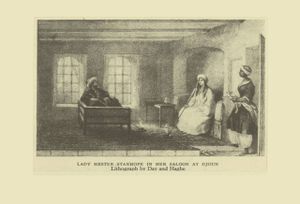

وفي عام 1813، بعد أن تركها عاشقها بروس وعاد الى بريطانيا، استقرت في لبنان حيث شيدت لنفسها قصراً يشبه القلعة فوق دير مهجور في قرية جون، ذات السبع روابي، على بعد ثمانية أميال من صيدا. وعـُرف قصرها بين الأهالي باسم "دار الست"[2]. واتخذت زي النساء المحلي فلبست عمامة ومداساً برأس منعكف، وصارت تدخن النارجيلة وتحمل السوط والخنجر، وشرعت تدرس اللغة العربية وولعت بعلم النجوم والخيمياء، وأحاطت نفسها بحرس من الألبان وحاشية من الزنوج وفرضت عليهم ان يسلكوا معها حسب قواعد التشريفات الملكية.

الواقع أنها استطاعت ان تكون ذات نفوذ وسلطة كبيرة جدا بين سكان المناطق المجاورة، ولا سيما الدروز منهم، فكانوا يحترمونها ويطيعون امرها الى درجة تبعث على الدهشة. في البداية رحب بها الأمير بشير شهاب الثاني، إلا تدخلها المستمر في شئون الدروز وإيوائها لمئات من اللاجئين من المناحرات بين القادة الدروز، جعله ينأى عنها. وعندما فتح ابراهيم باشا الشام أدرك ما لها من نفوذ وطلب منها أن تقف على الحياد، ولكن الحياد لم يكن من شيمتها فصارت من اشد الناس طعناً في الحكم المصري.

كان لستانهوب جواسيس يعملون في المدن الشامية الكبيرة، وكانت مراسلاتها ومؤامراتها مع الشيوخ والباشوات متصلة، وكانت لها يد في اثارة الدروز على الحكم المصري.

الحملة الأثرية

وقد قامت بحملة للبحث عن الكنوز المدفونة في مدينة عسقلان وأرادت من الحكومة البريطانية دفع تكاليفها، إلا أن الحملة لم تعثر على شيء ولم تعوضها الحكومة البريطانية. فوجدت نفسها غارقة في الديون، وبأمر من اللورد پالمرستون، تم خصم تلك الديون من الراتب التي كانت تتلقاه من الحكومة البريطانية لدائنيها في سوريا. وقد اشتكت من ذلك دون جدوى إلى الملكة ڤيكتوريا.

According to Charles Meryon, she came into possession of a medieval Italian manuscript copied from the records of a monastery somewhere in Syria. According to this document, a great treasure was hidden under the ruins of a mosque at the port city of Tel Ashkelon which had been lying in ruins for 600 years.[3] In 1815, on the strength of this map, she travelled to the ruins of Ashkelon on the Mediterranean coast north of Gaza,[4] and persuaded the Ottoman authorities to allow her to excavate the site. The governor of Jaffa, Muhammad Abu Nabbut was ordered to accompany her. This resulted in the first archaeological excavation in Palestine.

[Lady Stanhope] and Meryon correctly analyzed the history of the structure in Ashkelon before methods of modern archaeological analyses were known or used.

— ArchyFantasies، Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope: The First Modern Excavator of the Holy Land

In what might be rightfully called the first stratigraphical analysis of an archaeological site, [Meryon] reported that "there was every reason to believe that, in the changes of masters which Ascalon had undergone, the place in which we were now digging had originally been a heathen temple, afterwards a church, and then a mosque". It must be remembered that at the same time in Greece, excavators blissfully ignorant of stratigraphy boasted only of the quantity and artistic quality of their finds.

— Silberman، Restoring the Reputation of Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope, Neil Asher Silberman, BAR 10:04, Jul-Aug 1984.

While she did not find the hoard of three million gold coins reportedly buried there, the excavators unearthed a seven-foot headless marble statue. In an action which might seem at odds with her meticulous excavations, Stanhope ordered the statue to be smashed into "a thousand pieces" and thrown into the sea.[3] She did this as a gesture of goodwill to the Ottoman government, in order to show that her excavation was intended to recover valuable treasures for them, and not to loot cultural relics for shipment back to Europe, as so many of her countrymen were doing at this time.[5]

The statue dug up by Lady Hester at Ashkelon was therefore a dangerously tempting prize. Though headless and fragmentary, it was the first Greco-Roman artifact ever excavated in the Holy Land, a distinction that even Dr. Meryon recognized. Meryon was overjoyed with this discovery, and he supposed it to be the statue of a "deified king", perhaps one of the successors of Alexander the Great or even Herod himself. But Lady Hester did not share her physician’s antiquarian enthusiasm, for she had a great deal personally at stake. She feared that if she paid too much attention to it, "malicious people might say I came to look for statues for my countrymen, and not for treasures for the [Sublime] Porte", the customary phrase to describe the palace of the Sultan himself.

— Neil Asher Silberman، Restoring the Reputation of Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope

Stanhope was not digging the ruins in Ashkelon for her own personal greed and gain. She appeared to be doing so in order to elevate the region of the world she had come to call home, looking to return the gold to the Ottoman Sultan. Also, the destruction of the statue was done in order to prove her devotion and disprove the idea that she was just trying to pillage Palestine for Britain. Likewise, her excavations were quite methodical, well recorded for the time, and the statue was documented before its destruction. All of these things were unusual techniques for the time, and thus makes Stanhope’s excavation unique and valuable to history. I quite agree with Silberman’s conclusion that Stanhope’s excavation "might be rightfully called the first modern excavation in the history of archaeological exploration of the Holy Land".

— ArchyFantasies، Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope: The First Modern Excavator of the Holy Land

Her expedition paved the way for future excavations and tourism to the site.[6]

الحياة بين اللبنانيين

Lady Hester settled near Sidon, a town on the Mediterranean coast in what is now Lebanon, about halfway between Tyre and Beirut. She lived first in the disused Mar Elias monastery at the village of Abra, and then in another monastery, Deir Mashmousheh, southwest of the Casa of Jezzine.[بحاجة لمصدر] Her companion, Miss Williams, and medical attendant, Dr Charles Meryon, remained with her for some time; but Miss Williams died in 1828, and Meryon left in 1831, only returning for a final visit from July 1837 to August 1838.[7] When Meryon left for England, Lady Hester moved to a remote abandoned monastery at Joun, a village eight miles from Sidon, where she lived until her death. Her residence, known by the villagers as Dahr El Sitt, was at the top of a hill.[8] Meryon implied that she liked the house because of its strategic location, "the house on the summit of a conical hill, whence comers and goers might be seen on every side."

At first she was greeted by emir Bashir Shihab II, but over the years she gave sanctuary to hundreds of refugees of Druze inter-clan and inter-religious squabbles and earned his enmity.[بحاجة لمصدر] In her new setting, she wielded almost absolute authority over the surrounding districts and became the de facto ruler of the region.[9] Her control over the local population was enough to cause Ibrahim Pasha, when about to invade Syria in 1832, to seek her neutrality. Her supremacy was maintained by her commanding character, and by the belief that she possessed the gift of divination.[7] She kept up a correspondence with important people and received curious visitors who went out of their way to visit her.

Finding herself deeply in debt, she used her pension from England in order to pay off her creditors in Syria. From the mid-1830s she withdrew ever more from the world, and her servants began to steal her possessions, because she was less and less able to manage her household in her reclusive state. Stanhope may have suffered from severe depression; it has been suggested that, alternatively, she had become prematurely senile. At any rate, in her last years she would not receive visitors until dark, and even then, she would let them see only her hands and face. She wore a turban over her shaven head.

Lady Hester died in her sleep in 1839. She died destitute; Andrew Bonar and Robert Murray M'Cheyne, who visited the region a few weeks' later, reported that after her death, "not a para of money was found in the house."[10]

وفاتها

لم يسترح منها ابراهيم باشا إلا بعد ان ماتت في عام 1839م، فدفنت في مكانها، وكان عمرها لا يتجاوز الثالثة والستين، وقيل انها كانت عند موتها وحيدة مفلسة.

أعمالها

- C L Meryon - Memoirs of the Lady Hester Stanhope (1845), Travels of Lady Hester Stanhope (1846)

في الإعلام

- 1837: Letitia Elizabeth Landon's poetical illustration

"Djouni: the Residence of Lady Hester Stanhope". to an engraving of a painting by William Henry Bartlett was published in Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1838.[11]

- 1844: In Eothen by Alexander Kinglake, chapter VIII is devoted to Lady Hester Stanhope

- 1866: John Greenleaf Whittier's best-known poem, Snow-Bound, includes a description of a visit to Stanhope by the American preacher Harriet Livermore, "startling on her desert throne | The crazy Queen of Lebanon."[12]

- 1876: George Eliot's novel Daniel Deronda mentions Lady Hester Stanhope, book one, chapter seven, speaking of her as "Queen of the East".[13]

- 1876: Louisa May Alcott's novel Rose in Bloom mentions Lady Hester Stanhope, chapter 2.

- 1882: William Henry Davenport Adams's non-fiction book 'Celebrated Women Travellers of the Nineteenth Century' devotes a chapter to Lady Hester Stanhope.

- 1922: Hester Stanhope's travels are recalled by Molly Bloom in Ulysses by James Joyce.

- 1924: Hester Stanhope's story is told by Pierre Benoit in "Lebanon's Lady of the Manor"

- 1958: Lady Hester Stanhope is referred to in the English author Georgette Heyer's historical romance novel of the Regency period entitled Venetia, Chapter 4.

- 1961: In the novel Herzog by Saul Bellow, Herzog compares his wife's writing style to that of Lady Hester Stanhope.

- 1962: In the film Lawrence of Arabia, Prince Faisal suggests Lawrence is "another of these desert-loving Englishmen" and mentions Stanhope as an example.[14]

- 1967: Lady Hester Stanhope was the basis for the character of Great-Aunt Harriet in Mary Stewart's novel The Gabriel Hounds.

- 1986: In the 1986 TV movie Harem, the character Lady Ashley was very loosely based on Lady Hester Stanhope. See Harem (1986 TV Movie)

- 1995: Queen of the East, television movie about Stanhope, starring Jennifer Saunders[15] ISBN 0-7733-2303-1

- 2014: Brett Josef Grubisic's comic novel, This Location of Unknown Possibilities, describes an abandoned Canada-set attempt to produce a television biopic about Lady Hester Stanhope's travels.

- 2024: The Diamond of London by Andrea Penrose is a biographical novel based on the life of Lady Hester Stanhope as she fights convention in pursuit of freedom and adventure.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ببليوجرافيا

- Kirsten Ellis - Star of the Morning, The Extraordinary Life of Lady Hester Stanhope (2008)

- Lorna Gibb - Lady Hester: Queen of the East (2005)

- Virginia Childs - Lady Hester Stanhope (1990)

- Doris Leslie - The Desert Queen (1972)

- Joan Haslip - Lady Hester Stanhope (1934)

المصادر

- ^ حمزة عليان (2009-07-05). "صورة الليدي الإنكليزية حرّضت الدروز على الحكم المصري". جريدة القبس الكويتية. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ Memoirs of the Lady Hester Stanhope

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةSilberman - ^ The Leon Levy expedition to Ashkelon Archived 12 يونيو 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope: The First Modern Excavator of the Holy Land by ArchyFantasies

- ^ The Eccentric English Lady Who Introduced Archaeology to the Holy Land

- ^ أ ب Chisholm 1911, p. 775.

- ^ Stanhope, Hester Lucy, Lady; Meryon, Charles Lewis (1845). Memoirs of the Lady Hester Stanhope, as related by herself in conversations with her physician. London: Henry Colburn. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl Stanhope | British politician and scientist". Encyclopedia Britannica (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- ^ Harman, Allan, ed. (1996). Mission of Diiscovery: The Beginnings of Modern Jewish Evangelism. Christian Focus Publications. p. 203.

- ^ Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1837). "picture". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1838. Fisher, Son & Co.Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1837). "poetical illustration". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1838. Fisher, Son & Co.

- ^ "Representative Poetry Online".

- ^ Rignall, John, 1942- (2011). George Eliot, European novelist. Farnham, Surrey, England: Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-4094-2235-8. OCLC 732959021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Bolt, Robert. "Lawrence of Arabia" (PDF). DailyScript.com. Daily Script. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ DVD BFS Video

وصلات خارجية

- Archival material relating to الليدي هستر ستانهوپ listed at the UK National Register of Archives

- Works by or about الليدي هستر ستانهوپ in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2016

- مواليد 1776

- وفيات 1839

- رحالة

- People claiming to have paranormal abilities

- ثورة الدروز

- صانعو المشرق العربي المعاصر

- تاريخ لبنان

- 18th-century English people

- 18th-century English women

- 19th-century English memoirists

- 19th-century English women writers

- 19th-century British archaeologists

- 19th-century British women scientists

- 19th-century antiquarians

- 19th-century letter writers

- 19th-century travelers

- Daughters of British earls

- English political hostesses

- Archaeology of Israel

- Archaeologists of the Near East

- Stanhope family

- Female travelers

- British women archaeologists

- Women of the Regency era

- British expatriates in the Ottoman Empire

- People from Chevening, Kent

- عسقلان

- Shipwreck survivors