الزراعة في العصور الوسطى

الزراعة في العصور الوسطى describes the farming practices, crops, technology, and agricultural society and economy of Europe from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 to approximately 1500. The Middle Ages are sometimes called the Medieval Age or Period. The Middle Ages are also divided into the Early, High, and Late Middle Ages. The early modern period followed the Middle Ages.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الثورة الزراعية

خلفية

بدَّل نمو الصناعة والتجارة، وانتشار الاقتصاد النقدي، وازدياد الطلب على العمال في المدن، بدل هذا كله نظام الزراعة تبديلاً كبيراً. ذلك أن البلديات لحرصها على أن تظفر بعمال جدد أعلنت أن أي شخص يقيم في مدينة 366 يوماً دون أن يطلبه سيد إقطاعي، ويتحقق من شخصيته، ويستولي عليه لأنه من أرقاء أرضه، أي شخص تنطبق من هذه الشروط يصبح من تلقاء نفسه حراً، يتمتع بحماية قوانين حكومة المدينة وسلطانها. وذهبت فلورنسا إلى أبعد من هذا فدعت في عام 1106 جميع الفلاحين المقيمين في القرى المجاورة لها للمجيء إليها والإقامة فيها أحراراً؛ ودفعت بولونيا Bologna وغيرها من المدن المال إلى سادة الإقطاع لكي يسمحوا لأرقاء أراضيهم بأن ينتقلوا إلى المدن. وفر عدد كبير من أرقاء الأرض أودعوا ليفلحوا أرضين جديدة في شرق نهر الإلب، وأصبحوا فيها أحراراً من تلقاء أنفسهم.

الإقطاع

أما الذين بقوا في ضياع سادة الإقطاع فقد أخذوا يعارضون في أداء الضرائب والرسوم الإقطاعية التي أضحت لطول العهد بأدائها مقررة واجبة الأداء؛ ونشأت من هذه المعارضة متاعب جمة. وحذا كثير من أرقاء الأرض حذو عمال المدن فأنشئوا لهم جمعيات ريفية، وأقسموا أن يعملوا مجتمعين للامتناع عن أداء الرسوم والضرائب الإقطاعية، ثم سرقوا أو أتلفوا ما عند سادتهم من وثائق تسجيل استرقاقهم أو التزاماتهم، وأحرقوا قصور المعاندين من أولئك السادة، وأنذرهم بأنهم سيغادرون أملاكهم إذا لم يجيبوا مطالبهم. وفي عام 1100 أعلن أرقاء الأرض في سانت ميشيل- ده- بوفيه أنهم سيتزوجون من تلك الساعة بأية امرأة يرغبون في زواجها، وسيتزوجون بناتهم من أي شخص يرغبون فيه. وفي عام 1202 رفض أرقاء الأرض في سانت أرنول-دى-كرپي St. Arnoul de Crepy أن يؤدوا إلى سيدهم رئيس الدير ضريبة الأموات التقليدية أو الغرامة التي تفرض عليهم إذا زوجوا بناتهم خارج أملاك سيدهم. وشبت فتن أخرى من هذا النوع في أكثر من عشر مدن منتشرة من فلاندرز إلى أسبانيا، حتى وجد سادة الإقطاع أن من العسير عليهم أن يحصلوا على ربح من استخدام أرقاء الأرض، وزادت هذه الصعوبة أمامهم على مر الأيام. ذلك أ ضروب المقاومة المتزايدة كانت تتطلب منهم إشرافاً مستمراً كثير النفقة في كل مرحلة من مراحل العمل؛ وكان عمل هؤلاء الأرقاء في حوانيت الضيعة أكثر نفقة وأقل جودة من العمل الحر الذي يخرج السلع نفسها في المدن.

وأراد سادة الإقطاع أن يستبقوا الفلاحين في أرضهم، ويجعلوا عملهم مربحاً لأولئك السادة، فاستبدلوا بالقروض الإقطاعية القديمة مقادير من المال تؤدي دفعة واحدة، وباعوا أرقاء الأرض حريتهم بأثمان يؤدونها من مدخراتهم، وأجروا مساحات متزايدة من أرضهم إلى الفلاحين الأحرار بأجر نقدي، واستأجروا عمالاً أحراراً يعملون في حوانيت ضياعهم. وحذت أوربا الغربية حذو بلاد الشرق الإسلامية والبيزنطية فشرعت من بداية القرن الحادي عشر تنتقل انتقالاً يزداد عاماً بعد عام من الدفع عيناً في أكثر الأحوال إلى الدفع نقداً في معظمها. واشتدت رغبة ملاك الأراضي الإقطاعيين في الحصول على السلع المصنوعة التي يعرضها التجار عليهم، فزادت في المال يبتاعون به هذه السلع؛ ولما ساروا إلى قتال المسلمين في الحروب الصليبية كانوا أحوج إلى المال منهم إلى الطعام والبضائع. كذلك كانت الحكومات تطالب بأداء الضرائب نقداً لا عيناً؛ فلم ير الملاك بداً من الخضوع إلى مقتضيات الظروف، فباعوا محصولاتهم بالنقود العاجلة بدل أن يستهلكوها بالهجرة الشاقة المتعبة من قصر ريفي إلى قصر آخر مثله. وكان هذا الانتقال إلى الاقتصاد النقدي كثير النفقة على الملاك الإقطاعيين. ذلك أن إيجار أرضهم والأموال التي كانوا يحصلون عليها من الزراع نظير الرسوم المفروضة عليهم قد أصبح لها من الثبات في العصور الوسطى ما للعادات المألوفة، ولم يكن في مقدورهم أن يزيدوها بنفس السرعة التي تنخفض بها قيمة النقد؛ ولذلك اضطر كثيرون من الأشراف إلى بيع أرضهم- وباعوها عادة إلى رجال الطبقة الوسطى الناشئة. وحسبنا دليلاً على هذا أن بعض النبلاء قد ماتوا من زمن بعيد أي منذ عام 1250 وهو لا يملكون أرضاً، ومنهم من مات فقيراً معدماً(115). وكان من نتيجة هذه الأحوال أن أعتق فليب الجميل ملك فرنسا جميع أرقاء الأراضي الملكية في أوائل القرن الرابع عشر، وأن أمر ابنه لويس العاشر في عام 1315 بتحرير جميع أرقاء الأرض "بشروط عادلة صالحة"(166). وأخذ نظام رقيق الأرض يتلاشى شيئاً فشيئاً في عدد من البلاد المختلفة الواقعة غرب نهر الإلب وذلك في أوقات مختلفة من بداية القرن الثاني عشر إلى نهاية القرن السادس عشر، وحلت محلها ملكية الفلاحين لأرضهم، وتقسمت ضياع الإقطاع الكبرى إلى مزارع صغيرة، وحصل الفلاحون في القرن الثالث عشر على درجة من الحرية والرخاء لم يستمتعوا بمثلها مدى ألف عام. وفقدت القرى المحاكم الإقطاعية ما كان لها من سلطان على الفلاحين، وأخذ سكان القرى يختارون حكامهم، ولم يكن هؤلاء يقسمون يمين الولاء لسيد الإقطاع المالك لأرضهم بل للملك نفسه. على أن تحرير رقيق الأرض في أوربا الغربية لم يتم كله قبل عام 1789، فقد ظل عدد كبير من سادة الإقطاع يطالبون بحقوقهم القديمة من الوجهة القانونية، ولقد حاولوا في القرن الرابع عشر أن يستعيدوها من الوجهة العملية؛ غير أن الحركة التي تهدف إلى العمل الحر المنتقل لم يكن يستطاع وقفها طالما كانت التجارة والصناعة آخذتين في النماء.

وكان الحافز الجديد للحرية، مضافاً إلى اتساع الأسواق الزراعية، من أسباب تحسن أساليب الزراعة، وأدواتها، ومحصولاتها، كما كان تكاثر سكان المدن، وازدياد الثراء، وأساليب الجديدة التي يسرت الأعمال التجارية والمالية÷ كل هذا كان سبباً في اتساع نطاق الاقتصاد الريفي وزيادة غناه. وتطلبت الصناعات الجديدة محصولات صناعية غير التي كانت موجودة من قبل- قصب السكر، وبذر اليانسون، والكمون، والكتان، والعنب الهندي، والزيوت النباتية والأصباغ. وكان قرب المدن المزدحمة بالسكان مشجعاً على تربية الماشية، وصناعة منتجات الألبان، وغرس حدائق الخضر. وجرت السفن بالخمور في الأنهار وفي البر والبحر من آلاف الكروم المنتشرة في أودية التيبر، والآرنو، والبو، والوادي الكبير، والتاجه، والإبرة، والرون، والجروند، والجارون، واللوار، والسين، والموزل، والموز، والرين، والدانوب، وجرت السفن بهذه الخمور لتفرج كرب العمال الكادحين في حقول أوربا، حوانيتها، وغرف الحاسبين فيها؛ وحتى إنجلترا نفسها كانت تعصر الخمر في الفترة الممتدة من القرن الحادي عشر إلى القرن السادس عشر. وخرجت الأساطيل الضخمة في البحر البلطي، وبحر الشمال لتصيد منهما الرنكة وغيرها من أنواع السمك لتطعم المدن الجائعة التي تكثر فيها أيام الصوم، ويرتفع فيها ثمن اللحم؛ فكانت يارموث Yarmouth مدينة بحياتها إلى تجارة الرنكة، وأقر تجار لوبك بفضلها عليهم بأن نقشوا الرنكة على مقاعدهم في الكنيسة(117)، واعترف الهولنديون الشرفاء بأنهم "شادوا على الرنكة" مدينة أمستردام الشامخة(118).

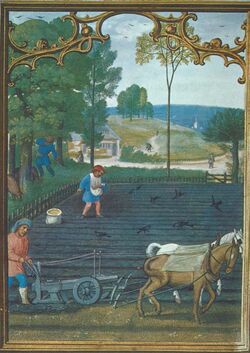

الحقول

وتحسنت أساليب الزراعة الفنية على مهل، فلقد تعلم المسيحيون من العرب في أسبانيا، وصقلية، وبلاد الشرق، وأدخل الرهبان البندكتيون والسسترسيون Cistercians الأساليب الرومانية القديمة والإيطالية الحديثة الخاصة بالزراعة، وتربية الماشية، والاحتفاظ بخصب التربة في الأقطار الواقعة شمال جبال الألب؛ وترك الزراع في الضياع الجديدة يبتكرون ويغامرون كما يشاءون ولم يفرض عليهم تقسيم أراضيهم بين المزروعات المختلفة. وكان الزراع الذين يفلحون في القرن الثالث عشر حقول فلاندرز المستحصلة من المستنقعات يتبعون الدورة الزراعية الثلاثية، فكانت الأرض تزرع كل عام ولكن خصبها كان يجدد مرة كل ثلاث سنين بزرع الكلأ الذي يتخذ غذاء للحيوان أو البقول. وكان زوجان من الثيران القوية يجران المحاريث ذات السهام الحديدية تتعمق الأرض أكثر من ذي قبل. غير أن الكثرة الغالبة من المحاريث ظلت مع ذلك تصنع من الخشب (1300). ولم يكن يعرف التسميد إلا أصقاع قليلة، وقلما كانت عجلات العربات تطوق بإطار من حديد. وكانت تربية الماشية من الأعمال الشاقة لطول فترات الجفاف؛ ولكن القرن الثالث عشر شهد التجارب الأولى في تهجين السلالات وأقلمتها. ولم تتقدم صناعة مستخرجات الألبان، فلم تكن البقرة العادية في القرن الثالث عشر تدر إلا قليلاً من اللبن، وقلما كان يصل إلى رطل واحد في الأسبوع (مع أن البقرة الحسنة التربية تنتج الآن ما بين عشرة أرطال وثلاثين رطلاً من الزبد في الأسبوع الواحد).

وبينما كان السادة في أوربا يقاتل بعضهم بعضاً، كان فلاحوها يخوضون معارك أعظم شأناً، وتتطلب من الشجاعة والبطولة ما يسمو على المعارك الحربية، ولا يتغنى بمديحهم إنسان؛ تلك هي معارك الإنسان مع الطبيعة. فقد طغى البحر بين القرنين الحادي عشر والثالث عشر خمساً وثلاثين مرة على الجسور، وأغرق الأراضي الوطيئة، وشق خلجاناً وأجواناً جديدة في البقاع التي كانت من قبل أرضاً صلبة، وأهلك مائة ألف من السكان في مائة عام. ونقل الفلاحون أهل هذه الأقاليم في خلال الفترة الممتدة من القرن الحادي عشر إلى القرن الرابع عشر بإشراف أمرائهم ورؤساء أديرتهم جلاميد الصخر من اسكنديناوة وألمانيا وشادوا بها "السور الذهبي" الذي أنشأ البلجيكيون والهولنديون وراءه دولتين من أعظم دول التاريخ كله حضارة، وانتزعت بذلك آلاف الأفدنة من البحر، ولم يستهل القرن الثالث عشر حتى كانت شبكة من القنوات تشق الأراضي الوطيئة. واحتفر الإيطاليون بين عامي 1179و1257 القناة العظمى Naviglio Grande بين بحيرة مجيوري ونهر البو فأخصبوا بها 86.485 فداناً، وأحال المهاجرون القادمون من فلاندرز، وفريزيا Frisia، وسكسونيا، وأرض الرين مستنقعات مورن Mooren الواقعة بين نهر الإلب والأودر حقولاً غنية. وقطعت غابات فرنسا الزائدة على الحاجة شيئاً فشيئاً وحلت مكانها الضياع التي ظلت تطعم فرنسا خلال الاضطراب السياسي الذي دام قروناً طوالاً. ولعل هذه البطولة الجماعية التي بذلت في تقطيع الغابات، وتجفيف المستنقعات، وإرواء الأرض وزراعتها، لا الانتصارات الحربية أو التجارية، هي العامل الأساسي الذي أدى آخر الأمر إلى انتصار الحضارة الأوربية في الأعوام السبعمائة الأخيرة.

أملاك المزارعين

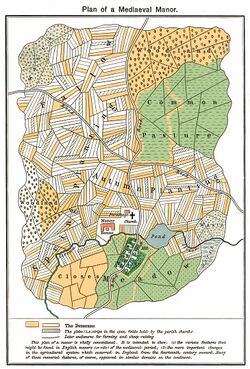

Farmers were not equal in the amount of land they farmed. In a survey of seven English counties in 1279, perhaps typical of Europe as a whole, 46 percent of farmers held less than 10 acres (4.0 ha), which was insufficient land to support a family. Some were completely landless, or possessed only a small garden adjacent to their house. These poor farmers were often employed by richer farmers, or practiced a trade in addition to farming.[1]

Thirty-three percent of farmers held about one-half virgate of land (12 acres (4.9 ha) to 16 acres (6.5 ha)), sufficient in most years to support a family. Twenty percent of farmers held about a full virgate, sufficient not only to support a family but to produce a surplus. A few farmers accumulated more than a virgate of land and thus were relatively wealthy, although not belonging to the nobility. These rich farmers might have tenants of their own and would hire labor to work their lands.[1]

Thirty-two percent of arable land was held by the lord of the manor. The farmers of the manor were required to work for a specified number of days per year on the lord's land or to pay rent to the lord on the land they farmed.[2]

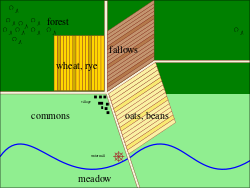

المحاصيل

In the late Roman Empire in Europe the most important crops were bread wheat in Italy and barley in northern Europe and the Balkans. Near the Mediterranean Sea viticulture and olives were important. Rye and oats were only slowly becoming major crops.[3] The Romans introduced viticulture to more northerly areas such as Paris and the valleys of the Moselle and Rhine rivers.[3] Cultivation of olives in medieval France was traditional on the southeastern coast bordering on Italy, but apparently the cultivation of olives in Languedoc on a large scale began in areas only in the 15th century.[4][5][6]

In Roman times, spelt, a kind of wheat, was the most common grain grown on the upper Danube River in Swabia, Germany, and spelt continued to be an important crop in many areas of Europe throughout medieval times. Emmer wheat was of much less importance in Swabia and most of Europe. Bread wheat was relatively unimportant in Swabia.[7]

In the eighth through 11th century, in northern France, the most important crops were (in approximate order) rye (Secale cereale), bread wheat, barley, and, oats (Avena sativa). Barley and oats were the most important crops in Normandy and Brittany.[8] Rye is more winter-hardy and tolerant of poor soils than wheat, and thus became the dominant crop on many marginal and northernmost European sites.[9] Another hardy crop, bere, a kind of barley, was grown in Scandinavia and England and especially in marginal agricultural areas in Scotland.[10]

In the lowlands of the Netherlands and adjacent France, soil influenced the crops planted. On sandy soils, in a three-field system, wheat was nearly absent as a crop with rye planted as a winter crop and oats and barley being the principle spring-planted crops. On more fertile loess and loamy soils, wheat, including spelt, became much more important replacing rye in many areas. Other crops included pulses (beans and peas) and fruits and vegetables. Farmers of loess and loamy soils planted a wider variety of crops than those on sandy soils.[11]

In Wiltshire England in the 13th and 14th centuries, wheat, barley, and oats were the three most common crops, with varying percentages of each on different manors. Legumes were planted on up to 8 percent of the common fields.[12] In addition to the grain crops in the common fields of the open-field system, farmer's houses usually had a small garden (croft) near their house in which they grew vegetables such as cabbages, onions, peas and beans; an apple, cherry or pear tree; and raised a pig or two and a flock of geese.[13]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

المواشي

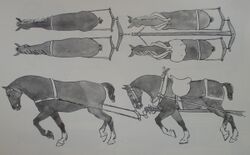

Livestock was more important in northern Europe than in the Mediterranean area where dry weather in summer reduced the fodder available for animals. Near the Mediterranean, sheep and goats were the most important farm animals and transhumance (seasonal movement of livestock) was common. In northern Europe cattle, pigs, and horses were also important.[3] Mediterranean soils were lighter than those commonly found in northern Europe, thus reducing the need of Mediterranean farmers for oxen and horses as draft animals.[14] Cattle, especially oxen, were vital in northern Europe as draft animals. Plow teams, ideally comprising eight oxen, were necessary to plow the heavy soils. Few farmers were wealthy enough to own a full team and thus plowing required cooperation and sharing of draft animals among farmers. Horses in Roman times were owned mostly by the wealthy but they were increasingly used as draft animals to replace oxen after about 1000. Oxen were cheaper to own and maintain, but horses were faster.[15] Pigs were the most important animals raised for meat in medieval England and other parts of northern Europe. Pigs were prolific and required little care. Sheep produced wool, skin (for parchment), meat, and milk, though less valuable in the marketplace than pigs.[16]

الانتاجية

Crop yields in the Middle Ages were extremely low compared to those of the 21st century, although probably not inferior to those in much of the Roman Empire preceding the Middle Ages and the early modern period following the Middle Ages.[17] The most common means of calculating yield was the number of seeds harvested compared to the number of seeds planted. On several manors in Sussex England, for example, the average yield for the years 1350–1399 was 4.34 seeds produced for each seed sown for wheat, 4.01 for barley, and 2.87 for oats.[18] (By contrast, wheat production in the 21st century can total 30 to 40 seeds harvested for each seed sown.) Average yields of grain crops in England from 1250 to 1450 were 7 to 15 bushels per acre (470 to 1000 kg per ha).[19] Poor years, however, might see yields drop to less than 4 bushels per acre.[12] Yields in the 21st century, by contrast, can range upwards to 60 bushels per acre.[20] The yields in England were probably typical for Europe in the Middle Ages.

Scholars have often criticized medieval agriculture for its inefficiency and low productivity. The inertia of an established system was blamed. "Everyone was forced to conform to village norms of cropping, harvesting, and building."[21] Two reputed inefficiencies of the predominant open-field system were the communal management of land which resulted in less than optimal allocation of resources and the fact that farmers had small, scattered strips of land to cultivate which was wasting of time in traveling from one strip to another. Despite the reputed inefficiencies, the open-field system existed for roughly one thousand years over large parts of Europe and only disappeared slowly from 1500 to 1800.[22] Moreover, the replacement of the open-field system by privately owned property was fiercely resisted by many elements of society. The "brave new world" of a harsher, more competitive and capitalistic society from the 16th century onward destroyed the securities and certainties of land tenure in the open-field system.[23]

The "Postan Thesis" is also cited as a factor in the low productivity of medieval agriculture. Productivity suffered because of inadequate fertilization to keep the land productive. This was due to a shortage of pasture for farm animals and, thus, a shortage of nitrogen-rich manure to fertilize the arable land. Moreover, because of population growth after 1000, marginal lands, pasture, and woodlands were converted into arable lands which further reduced the number of farm animals and the quantity of manure.[24]

The earliest evidence of progress in increasing productivity comes in the 14th and 15th centuries from the Low Countries of the Netherlands and Belgium, and Flanders in northern France. The agricultural practices there involved the near elimination of fallow land by planting cover crops such as vetch, beans, turnips, spurry, and broom and high-value crops such as rapeseed, madder and hops. As opposed to the extensive agriculture of medieval times, this new technique involved intensive cultivation of small plots of land. Techniques of intensive cultivation quickly spread to Norfolk in England, agriculturally-speaking the most advanced area of England.[25] These advancements aside, it was the 17th century before England saw widespread increases in agricultural productivity in what was called the British Agricultural Revolution.[26]

The low level of medieval yields persisted in Russia and some other areas until the 19th century. In 1850, the average yield for grain in Russia was 600 kilograms per hectare (about 9 bushels per acre), less than one half the yield in England and the Low Countries at that time.[27]

المجاعات

Famines caused by crop failures and poor crop years were an ever present danger in medieval Europe. It was often not possible to relieve a famine in one area by importing grain from another area as the difficulty of overland transportation caused the price of grain to double for each 50 miles it was transported.[28]

One study concluded that famines in Europe occurred on an average every 20 years between the years 750 and 950. The principal causes were extreme weather and climatic anomalies which reduced agriculture production. Warfare was not found to be a major cause of famine.[29] A study of crop failures in Winchester, England from 1232 to 1349 found that harvest failure occurred an average of every 12 years for wheat and every 8 years for barley and oats. Localized famine may have occurred in years in which one or more crops failed. Weather was again identified as the chief cause. Climatic change may have played a part as the Little Ice Age may have begun between 1275 and 1300 with a consequent shortening of the growing season.[30]

Warfare was apparently responsible for a major famine in Hungary from 1243 to 1245. These were the years in the aftermath of the Mongol invasion and widespread destruction. Twenty to fifty percent of the population of Hungary is estimated to have died of hunger and war.[31]

The best known and most extensive famine of the Middle Ages was the Great Famine of 1315–1317 (which actually persisted to 1322) that affected 30 million people in northern Europe, of whom five to ten percent died. The famine came near the end of three centuries of growth in population and prosperity. The causes were "severe winters and rainy springs, summers and falls." Yields of crops fell by one-third or one-fourth and draft animals died in large numbers. The Black Death of 1347–1352 was more lethal, but the Great Famine was the worst natural catastrophe of the later Middle Ages.[32]

Technological innovation

The most important technical innovation for agriculture in the Middle Ages was the widespread adoption around 1000 of the mouldboard plow and its close relative, the heavy plow. These two plows enabled medieval farmers to exploit the fertile but heavy clay soils of northern Europe. In the Roman era and on light soils, the ard or scratch plow had sufficed. The mouldboard and heavy plows turned the soil over which facilitated the control of weeds and their incorporation into the soil, increasing fertility. Mouldboard plowing also produced the familiar ridge and furrow pattern of medieval fields which facilitated drainage of excess moisture. "By allowing for better field drainage, access [to] the most fertile soils, and saving of peasant labor time, the heavy plow stimulated food production and, as a consequence 'population growth, specialization of function, urbanization, and the growth of leisure.'"[33]

Two additional advances coming into general use in Europe around 1000 were the horse collar and the horseshoe. The horse collar increased the pulling capacity of a horse. The horseshoe protected a horse's hooves. These advances resulted in the horse becoming an alternative to slow-moving oxen as a draft animal and for transportation.[34][35]

These technological innovations and the additional agricultural production they stimulated resulted in Europe experiencing a large increase in population from 1000 (or earlier) to 1300, an increase that was reversed by the Great Famine and the Black Death of the 14th century.[36]

المراجع

- ^ أ ب Gies, p. 72

- ^ Gies, pp. 72-80

- ^ أ ب ت Pounds, p. 63

- ^ Ruas, Marie-Pierre (2005). "Aspects of early medieval farming from sites in Mediterranean France". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 14 (4): 400–415. doi:10.1007/s00334-005-0069-8. JSTOR 23419296. S2CID 128473218.

- ^ "The olive industry in France". ResearchGate.

- ^ Le Roy Ladurie, Emmanuel (1976), The Peasants of languedoc, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, p. 57

- ^ Rösch, Manfred; Jacomet, Stefanie; Karg, Sabine (1992). "The history of cereals in the region of the former Duchy of Swabia (Herzogtum Schwaben) from the Roman to the Post-medieval period: results of archaeobotanical research". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 1 (4): 193–231. doi:10.1007/BF00189499. JSTOR 23417098. S2CID 129589058.

- ^ Ruas, pp. 406-407

- ^ "Gramene Secale", http://archive.gramene.org/species/secale/rye_intro.html, accessed 2 Aug 2018

- ^ "Bere (barley)," https://beerandbrewing.com/dictionary/izxSEht6Z2/bere-barl, accessed 2 Aug 2018

- ^ Bakels, Corrie C. (21 June 2005). "Crops produced in the southern Netherlands and northern France during the early medieval period: a comparison". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 14 (4): 394–399. doi:10.1007/s00334-005-0067-x. S2CID 129060427.

- ^ أ ب "Field Systems and Demesne Farming on the Wiltshire Estates of Saint Swithun's Priory, Winchester, 1248-1340". The Agricultural History Review. 43 (1): 1–18. 1995. JSTOR 40275378.

- ^ Bennett, pp. 231-232

- ^ "Medieval Technology Pages - the Heavy Plow". Archived from the original on 2005-11-10. Retrieved 8 Aug 2018.قالب:SemiBareRefNeedsTitle

- ^ Moore, John H. (1961). "The Ox in the Middle Ages". Agricultural History. 35 (2): 90–93. JSTOR 3740550.

- ^ Gies, pp. 147-148

- ^ Erdkamp, Paul (2005), The Grain Market in the Roman Empire, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 35-54. Erdkamp accepts 8 to l as an average yield on the best wheat lands on the best farms in Sicily and higher still in Egypt during the Roman Empire. Climatic conditions for growing grain in northern Europe were more difficult for medieval farmers.

- ^ Brandon, P. F. (1972). "Cereal Yields on the Sussex Estates of Battle Abbey during the Later Middle Ages". The Economic History Review. 25 (3): 403–420. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1972.tb02184.x. JSTOR 2593429.

- ^ Broadberry, Stephen (2008). 'English Agricultural Output 1250–1450: Some Preliminary Estimates'.

- ^ Food and Agricultural Organization.http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/y5146e/y5146e07.htm, accessed 11 Aug 2018

- ^ Hopcroft, p. 48

- ^ Dahlman, Carl J. (1980), The Open Field System and Beyond, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 94-97

- ^ Campbell, Bruce M.S., "The land" in A Social History of England, 1200–1500, ed. by Rosemary Horrox and W. Mark Ormrod. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 237

- ^ Clark, Gregory (1992). "The Economics of Exhaustion, the Postan Thesis, and the Agricultural Revolution". The Journal of Economic History. 52 (1): 61–84. doi:10.1017/S0022050700010263. JSTOR 2123345. S2CID 154101916.

- ^ Campbell, Bruce M. S. (1983). "Agricultural Progress in Medieval England: Some Evidence from Eastern Norfolk". The Economic History Review. 36 (1): 26–46. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1983.tb01222.x. JSTOR 2598896.

- ^ Clark, p. 80

- ^ Blum, Jerome (1960). "Russian Agriculture in the Last 150 Years of Serfdom". Agricultural History. 34 (1): 3–12. JSTOR 3740859.

- ^ Heather, pp. 110-111

- ^ Newfield, Timothy P. (2013), "The Contours, Frequency and Causation of Subsistence Crises in Carolingian Europe (750-950 CE)" in Crisis Alimentarian en la Edad Media, Lleida, Spain: Universidad de Lleida, pp 118, 169

- ^ Dury, G. H. (1984). "Crop Failures on the Winchester Manors, 1232-1349". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 9 (4): 401–418. doi:10.2307/621777. JSTOR 621777.

- ^ Fara, Andrea (2017). "Production of and Trade in Food Between the Kingdom of Hungary and Europe in the Late Middle Ages and Early Modern Era (Thirteenth to Sixteenth Centuries): The Roles of Markets in Crises and Famines". The Hungarian Historical Review. 6 (1): 138–179. JSTOR 26370717.

- ^ Jordan, William Chester in Ecologies and Economies in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, edited by Scott G. Bruce, Leiden: Brill, pp. 45-51

- ^ Andersen, Thomas Barnebeck; Jensen, Peter Sandholt; Skovsgaard, Christian Volmar (January 2016). "The heavy plow and the agricultural revolution in Medieval Europe". Journal of Development Economics. 118: 133–149. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.08.006.

- ^ "Horse collar", https://www.britannica.com/technology/horse-collar, accessed 16 Aug 2018

- ^ "Horses in the Middle Ages," http://horsehints.org/MiddleAgesHorse.htm, accessed 16 Aug 2018

- ^ Pounds, pp. 119-123

للاستزادة

- Decker, Michael (2019). "Syriac Agriculture 350–1250". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 567–580. ISBN 9781138899018.