البنغال الهولندية

Dutch Bengal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1627–1825 | |||||||||

Dutch Bengal (in green) within Dutch India | |||||||||

| الوضع | Factory | ||||||||

| العاصمة | Pipely (1627–1635) Hugli-Chuchura (1635–1825) | ||||||||

| اللغات المشتركة | Dutch | ||||||||

| Director | |||||||||

• 1655–1658 | Pieter Sterthemius | ||||||||

• 1724–1727 | Abraham Patras | ||||||||

• 1785–1792 | Isaac Titsingh | ||||||||

• 1792–1795 | Cornelis van Citters Aarnoutszoon | ||||||||

• 1817–1825 | Daniel Anthony Overbeek | ||||||||

| الحقبة التاريخية | Imperialism | ||||||||

• Establishment of a trading post at Pipely | 1627 | ||||||||

| 1825 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Bengal was a directorate of the Dutch East India Company in Mughal Bengal between 1610 until the company's liquidation in 1800. It then became a colony of the Kingdom of the Netherlands until 1825, when it was relinquished to the British according to the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824. Dutch presence in the region started by the establishment of a trading post at Pipili in the mouth of Subarnarekha River in Odisha. The former colony is part of what is today called Dutch India.[1] Bengal was the source of 50% of the textiles and 80% of the raw silk imported from Asia by the Dutch.[2]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

History

From 1615 onward, the Dutch East India Company traded in the eastern part of Mughal Province of Bengal, Bihar & Orissa.

In 1627, the first trading post with a factory was established in Pipely Port in the coast of Utkal Plains. The port of Pipely (Pipilipattan in Odia) was situated on the confluence of Subarnarekha river of modern day Balasore district of Odisha.

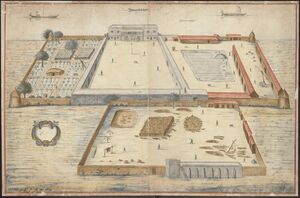

In 1635, a settlement was established in the proper Bengal at Chinsurah adjacent to Hooghly to trade in opium, salt, muslin, and spices.[3] In 1655, a separate organization, Directorate of Bengal, was created.[4] The factory was walled in 1687 to protect it against attacks and in 1740, during the directorship of Jan Albert Sichterman, rebuilt into a fort with four bastions. The fort was named Fort Gustavus in 1742, after governor-general Gustaaf Willem van Imhoff. Director Sichterman built a church tower in 1742, which was joined by a church building in 1765.[5] Dutch territorial property was confined to Chinsurah and Baranagore, which they received as a gift from the Nawab. It was for all purposes subordinate to the government at Batavia.[6]

Dutch factories were established not only at important centres like Patna, Fatuha, Dacca, and Malda but also at some interior villages like Kagaram, Motipur and Mowgrama.[7]

A famous Frenchman, General Perron who served as military advisor to the Mahrattas, settled in this Dutch colony, and built a large house here.

Trade thrived in Mughal Empire's most developed region Bengal Subah in the early eighteenth century, to such an extent that the administrators of the Dutch East India Company allowed Hooghly-Chinsura in 1734 to trade directly with the Dutch Republic, instead of first delivering their goods to Batavia. The only other Dutch East India Company settlement to have this right was Dutch Ceylon.

Dutch control over Bengal was waning in the face of Anglo-French rivalry in India in the middle of the eighteenth century, and their status in Bengal was reduced to that of a minor power with the British victory in the Battle of Plassey in 1757. In 1759, the Dutch tried in vain to curb British power in Bengal in the Battle of Chinsurah.

Dutch Bengal was occupied by British forces in 1795, owing to the Kew Letters written by Dutch stadtholder William V, Prince of Orange, to prevent the colony from being occupied by France. The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814 restored the colony to Dutch rule, but with the desire to divide the Indies into two separate spheres of influence, the Dutch ceded all their establishment on the Indian peninsula to the British with the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824.

Legacy

Fort Gustavus has since been obliterated from the face of Chinsurah, but much of the Dutch heritage remains. These include the Dutch cemetery, the old barracks (now Chinsurah Court), the Governor's residence, General Perron's house, now the Chinsurah College known as Hooghly Mohsin College and the old Factory Building, now the office of the Divisional Commissioner. Hugli-Chinsurah is now the district town of the Hooghly district in modern West Bengal.

Cossimbazar still has a Dutch cemetery. The Dutch cemetery in Karinga near Chhapra features a mausoleum for Jacob van Hoorn, who died in 1712.[8]

The Dutch church of Chinsurah was demolished in 1988 by the West Bengal Public Works Department.[9] The memorial tablets of deceased Dutch people, which used to be displayed in the church, were donated by the bishop of Calcutta to the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam in 1949.[10]

Trading posts

Dutch settlements in Bengal include:

- Dutch settlement in Rajshahi

- In Chhapra was a saltpeter factory (1666 -1781)(seized by British)

- Baleswar or Balasore (1675 -)

- Patna (1638)(1645-1651)(1651-1781)(seized by British)

- Cossimbazar or Kassamabazar

- Malda

- Mirzapur (in Bardhaman, West Bengal)

- Baliapal or Pipeli, the main port for the Dutch between 1627–1635

- Murshidabad (1710–1759)

- Rajmahal

- Dhaka (1665-)

- Sherpur

See also

References

- ^ De VOC site - Bengalen Archived 6 مايو 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Prakash, Om (2006). "Empire, Mughal". In McCusker, John J. (ed.). History of World Trade Since 1450. Vol. 1. Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 237–240. ISBN 0-02-866070-6. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ "The Dutch Cemetery in Chinsurah". www.dutchcemeterybengal.com (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 2017-04-21.

- ^ Datta, Kalikinkar (1948). The Dutch in Bengal and Bihar, 1740-1825 A.D. (in الإنجليزية). University of Patna. p. 2.

- ^ De Jong, Dick (14 March 2014). "Nearly fifteen years VOC service in Bengal: Jan Albert Sichterman" (PDF). Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ Datta, Kalikinkar (1948). The Dutch in Bengal and Bihar, 1740-1825 A.D. (in الإنجليزية). University of Patna. p. 4.

- ^ Datta, Kalikinkar (1948). The Dutch in Bengal and Bihar, 1740-1825 A.D. (in الإنجليزية). University of Patna. pp. 1–2.

- ^ Bauke van der Pol - Chhapra: Holland on the Ganges - The Lost Tomb

- ^ Majumdar, Diptosh (11 October 1988). "PWD vandals destroy historic church". Calcutta Times. Kolkata. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ The Dutch in India & Chinsurah by Dr Oeendrila Lahiri, p. 16

Further reading

- Lequin, Frank. (1982). Het personeel van de Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie in Azie in de achttiende eeuw, meer in het bijzonder in de vestiging Bengalen (The staff of the Dutch East India Company in Asia in the eighteenth century, in particular the establishment in Bengal). Thesis (Ph. D.), University of Leiden. ISBN 9789090000947; OCLC 13375077

External links

- Dutch in Chinsurah

- Dutch Cemetery Bengal, Chinsurah Archived 9 أبريل 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Short description matches Wikidata

- India articles missing geocoordinate data

- All articles needing coordinates

- Dutch Bengal

- European colonisation in Asia

- Former trading posts of the Dutch East India Company

- Former settlements and colonies of the Dutch East India Company

- 1627 establishments in Dutch India

- 1825 disestablishments

- 19th-century disestablishments in the Dutch Empire

- States and territories disestablished in 1825