الإسلام النفطي

Petro-Islam is a neologism used to refer to the international propagation of the extremist and fundamentalist interpretations of Sunni Islam[1] derived from the doctrines of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, a Sunni Muslim preacher, scholar, reformer and theologian from Uyaynah in the Najd region of the Arabian Peninsula,[2][3][4][5][6] eponym of the Islamic revivalist movement known as Wahhabism.[2][3][4][5][6] This movement has been favored by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia[2][7][8] and the other Arab states of the Persian Gulf.

Its name derives from source of the funding, petroleum exports, that spread it through the Muslim world after the Yom Kippur War.[2][9][10] The term is sometimes called "pejorative"[11] or a "nickname".[9] According to Sandra Mackey the term was coined by Fouad Ajami.[12][13] It has been used by French political scientist Gilles Kepel,[14] Bangladeshi scholar Imtiyaz Ahmed,[15] and Egyptian philosopher Fouad Zakariyya,[16] among others.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Usage and definitions

The use of the term to refer to "Wahhabism", the dominant interpretation of Islam in Saudi Arabia, is widespread but not universal. Variations on or different uses of the term include:

- Use of resources by Saudi Arabia "to project itself as a major player in the Muslim world": the distribution of large sums of money from public and private sources in Saudi Arabia to advance Wahhabi doctrines and pursue the Saudi Arabian foreign policy.[17]

- Attempts by the Saudi rulers to use both Islam and its wealth to win the loyalty of the Muslim world.[16][18]

- Diplomatic, political, economic, and religious policies promoted by Saudi Arabia.[19]

- The type of Islam favored by petroleum-exporting Muslim-majority countries, particularly the other Gulf monarchies (United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Qatar, etc.), not just Saudi Arabia.[20]

- A "hugely successful" enterprise made up of a "colossal ensemble" of media and other cultural organs that has broken the "secularist and nationalist" monopoly of the state on culture, media and, "to a lesser extent", education; and is supported by both Islamists and socially conservative business "elements", who opposed the Arab nationalist ideologies of Nasserism and Baathism.[21]

- More conservative Islamic cultural practices (separation of the sexes, wearing of the hijab or a more complete hijab) brought back (to other Muslim states, such as Egypt, Pakistan, Bangladesh, etc.) from Gulf oil states by migrant workers.[22]

- A term used by secularists, particularly in Egypt, to refer to efforts to require the enforcement of sharia (Islamic law).[23]

- An Islamic interpretation that is "anti-woman, anti-intellectual, anti-progress, and anti-science... largely funded by the Saudis and Kuwaitis."[24]

Background

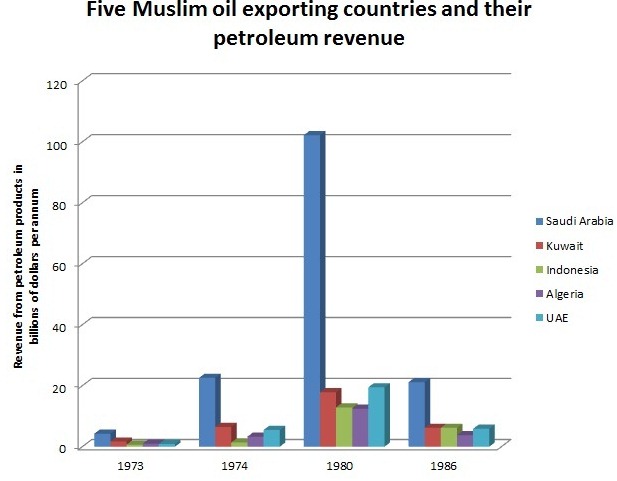

Years were chosen to shown revenue for before (1973) and after (1974) the October 1973 War, after the Iranian Revolution (1978-1979), and during the market turnaround in 1986.[27] Iran and Iraq are excluded because their revenue fluctuated due to the revolution and the war between them.[28]

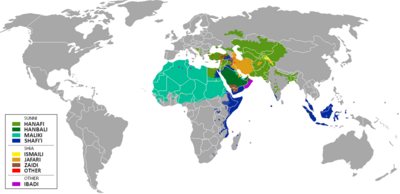

One scholar who spelled out the idea of petro-Islam in some detail is Gilles Kepel.[29][30] According to Kepel, prior to the 1973 oil embargo, religion throughout the Muslim world was "dominated by national or local traditions rooted in the piety of the common people." Clerics looked to their different schools of fiqh (the four Sunni Madhhabs: Hanafi in the Turkish zones of South Asia, Maliki in Africa, Shafi'i in Southeast Asia, plus Shi'a Ja'fari, and "held Saudi inspired puritanism" (using another school of fiqh, Hanbali) in "great suspicion on account of its sectarian character," according to Gilles Kepel.[31]

While the 1973 War (also called the Yom Kippur War) was started by Egypt and Syria to take back land won by Israel in 1967, the "real victors" of the war were the Arab "oil-exporting countries", (according to Gilles Kepel), whose embargo against Israel's western allies stopped Israel's counter offensive.[32]

The embargo's political success enhanced the prestige of those who embargoed and the reduction in the global supply of oil sent oil prices soaring (from $3 per barrel to nearly $12[33]) and with them, oil exporter revenues. That put Muslim oil exporting states in a "clear position of dominance within the Muslim world." The most dominant was Saudi Arabia, the largest exporter by far (see bar chart).[34][32]

Saudi Arabians viewed their oil wealth not as an accident of geology or history but connected to religion, a blessing by God of them, to "be solemnly acknowledged and lived up to" with pious behavior.[11][35][36]

With its new wealth the rulers of Saudi Arabia sought to replace nationalist movements in the Muslim world with Islam, to bring Islam "to the forefront of the international scene," and to unify Islam worldwide under the "single creed" of Wahhabism, paying particular attention to Muslims who had immigrated to the West (a "special target").[31]

Influence of "Petro-dollars"

According to scholar Gilles Kepel, (who devoted a chapter of his book Jihad to the subject -- "Building Petro-Islam on the Ruins of Arab Nationalism"),[14] in the years immediately after the 1973 War, 'petro-Islam' was a "sort of nickname" for a "constituency" of Wahhabi preachers and Muslim intellectuals who promoted "strict implementation of the sharia [Islamic law] in the political, moral and cultural spheres."[9]

In the coming decades, Saudi Arabia's interpretation of Islam became influential (according to Kepel) through

- the spread of Wahhabi religious doctrines via Saudi charities; an

- increased migration of Muslims to work in Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf states; and

- a shift in the balance of power among Muslim states toward the oil-producing countries.[14]

Author Sandra Mackey describes the use of petrodollars on facilities for the hajj such as by leveling hill peaks to make room for tents, providing electricity for tents and cooling pilgrims with ice and air conditioning, as part of "Petro-Islam", which she describes as a way of building the Muslim faithful's loyalty toward the Saudi government.[18][37]

Religious funding

The Saudi ministry for religious affairs printed and distributed millions of Qurans free of charge, along with doctrinal texts that followed the Wahhabi interpretation. In mosques throughout the world "from the African plains to the rice paddies of Indonesia and the Muslim immigrant high-rise housing projects of European cities, the same books could be found," paid for by Saudi Arabian government.[38]

Imtiyaz Ahmed, a religious scholar and professor of International Relations at University of Dhaka sees changes in religious practices in Bangladesh as linked to Saudi Arabia's efforts to promote Wahhabism through the financial help it provides countries like Bangladesh.[15] The Mawlid, the celebration of the Prophet Muhammad's birthday and formerly "an integral part of Bangladeshi culture" is no longer popular, while black burqas for women are much more so.[39] The discount on the price of oil imports Bangladesh receives does not "come free", according to Ahmed. "Saudi Arabia is giving oil, Saudi Arabia would definitely want that some of their ideas to come with oil."

Mosques

More than 1,500 mosques were built around the world from 1975 to 2000 paid for by Saudi public funds. The Saudi-headquartered and financed Muslim World League played a pioneering role in supporting Islamic associations, mosques, and investment plans for the future. It opened offices in "every area of the world where Muslims lived."[38] The process of financing mosques usually involved presenting a local office of the Muslim World League with evidence of the need for a mosque/Islamic center to obtain the offices 'recommendation' (tazkiya) to "a generous donor within the kingdom or one of the emirates."[41]

Saudi-financed mosques were generally built using marble 'international style' design and green neon lighting, in a break with most local Islamic architectural traditions, but following Wahhabi ones.[42]

Islamic banking

One mechanism for the redistribution of (some) oil revenues from Saudi Arabia and other Muslim oil-exporters, to the poorer Muslim nations of African and Asia, was the Islamic Development Bank. Headquartered in Saudi Arabia, it opened for business in 1975. Its lenders and borrowers were member states of Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC) and it strengthened "Islamic cohesion" between them.[43]

Saudi Arabians also helped establish Islamic banks with private investors and depositors. DMI (Dar al-Mal al-Islami: the House of Islamic Finance), founded in 1981 by Prince Mohammed bin Faisal Al Saud,[44] and the Al Baraka group, established in 1982 by Sheik Saleh Abdullah Kamel (a Saudi billionaire), were both transnational holding companies.[45]

Migration

By 1975, over one million workers, from unskilled country people to experienced professors – from Sudan, Pakistan, India, Southeast Asia, Egypt, Palestine, Lebanon and Syria – had moved to Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf states to work and returned after a few years with savings. Most of the workers were Arab and most were Muslim. Ten years later the number had increased to 5.15 million and Arabs were no longer in the majority. 43% (mostly Muslims) came from the Indian subcontinent. In one country, Pakistan, in a single year, (1983),[46]

the money sent home by Gulf emigrants amounted to $3 billion, compared with a total of $735 million given to the nation in foreign aid.... The underpaid petty functionary of yore could now drive back to his hometown at the wheel of a foreign car, build himself a house in a residential suburb, and settle down to invest his savings or engage in trade... he owed nothing to his home state, where he could never have earned enough to afford such luxuries.[46]

Muslims who had moved to Saudi Arabia, or other "oil-rich monarchies of the peninsula" to work, often returned to their poor home country following religious practice more intensely, particularly practices of Wahhabi Muslims. Having "grown rich in this Wahhabi milieu", it was not surprising that the returning Muslims believed that there was a connection between that milieu and "their material prosperity" and that when they returned, they followed religious practices more intensely, which followed Wahhabi tenants.[47] Kepel gives examples of migrant workers returning home with new affluence, asking to be addressed by servants as "hajja" rather than "Madame" (the old bourgeois custom).[42] Another imitation of Saudi Arabia adopted by affluent migrant workers was increased segregation of the sexes, including shopping areas.[42][48]

State leadership

In the 1950s and 1960s Gamal Abdul-Nasser, the leading exponent of Arab nationalism and the president of the Arab world's largest country had great prestige and popularity.

However, in 1967 Nasser led the Six-Day War against Israel which ended not in the elimination of Israel but in the decisive defeat of the Arab forces[49] and loss of a substantial chunk of Egyptian territory. This defeat, combined with the economic stagnation from which Egypt suffered, were contrasted with the perceived victory of the October 1973 war whose pious battle cry of Allahu Akbar replaced "Land! Sea! Air!" slogan of the 1967 war,[49][50] and with the enormous wealth of the resolutely non-nationalist Saudi Arabia.

This changed "the balance of power among Muslim states" toward Saudi Arabia and other oil-exporting countries. gaining as Egypt lost influence. The oil-exporters emphasized "religious commonality" among Arabs, Turks, Africans, and Asians, and downplayed "differences of language, ethnicity, and nationality."[51] The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, whose permanent Secretariat is located in Jeddah in Western Saudi Arabia, was founded after the 1967 war.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Criticism

At least one observer, The New Yorker magazine's investigative journalist Seymour Hersh, has suggested that petro-Islam is being spread by those whose motivations are less than earnest or pious.[52] Petro-Islam funding following the Gulf War, according to Hersh, "amounts to protection money" from the Saudi regime "to fundamentalist groups that wish to overthrow it."[53]

Egyptian existentialist Fouad Zakariyya has accused purveyors of Petro-Islam as having as their objective the protection of the oil wealth and "social relations" of the "tribal societies that possess the lion's share of this wealth," at the expense of the long-term development of the region and the majority of its people.[54] He further states that it is a "brand of Islam" that bills itself as "pure" but rather than being the Islam of the early Muslims has "never" been "seen before in history".[16]

Authors who criticize the "thesis" of Petro-Islam itself (that petrodollars have had a significant effect on Muslim beliefs and practices) include Joel Beinin and Joe Stork. They argue that in Egypt, Sudan and Jordan, "Islamic movements have demonstrated a high level of autonomy from their original patrons." The strength and growth of Muslim Brotherhood and other forces of conservative political Islam in Egypt can be explained, according to Beinin and Stork, by internal forces: the historical strength of the Muslim Brotherhood, sympathy for the "martyred" Sayyid Qutb, anger with the "autocratic tendencies" and the failed promises of prosperity of the Sadat government.[55]

See also

- Arab Cold War

- Islam in Saudi Arabia

- Islamic extremism

- Islamism

- List of Islamist terrorist attacks

- Political aspects of Islam

- Salafi movement

References

- ^ Musa, Mohd Faizal (2018). "The Riyal and Ringgit of Petro-Islam: Investing Salafism in Education". In Saat, Norshahril (ed.). Islam in Southeast Asia: Negotiating Modernity. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing. pp. 63–88. doi:10.1355/9789814818001-006. ISBN 9789814818001. S2CID 159438333.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Wagemakers, Joas (2021). "Part 3: Fundamentalisms and Extremists – The Citadel of Salafism". In Cusack, Carole M.; Upal, M. Afzal (eds.). Handbook of Islamic Sects and Movements. Brill Handbooks on Contemporary Religion. Vol. 21. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 333–347. doi:10.1163/9789004435544_019. ISBN 978-90-04-43554-4. ISSN 1874-6691.

- ^ أ ب Laoust, H. (2012) [1993]. "Ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhāb". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. J.; Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_3033. ISBN 978-90-04-16121-4.

- ^ أ ب Haykel, Bernard (2013). "Ibn ‛Abd al-Wahhab, Muhammad (1703-92)". In Böwering, Gerhard; Crone, Patricia; Kadi, Wadad; Mirza, Mahan; Stewart, Devin J.; Zaman, Muhammad Qasim (eds.). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 231–232. ISBN 978-0-691-13484-0. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ أ ب Esposito, John L., ed. (2004). "Ibn Abd al-Wahhab, Muhammad (d. 1791)". The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 123. ISBN 0-19-512559-2. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ أ ب "Ibn Abd al-Wahhab, Muhammad - Oxford Islamic Studies Online". www.oxfordislamicstudies.com. Oxford University Press. 2020. Archived from the original on July 12, 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Hasan, Noorhaidi (2010). "The Failure of the Wahhabi Campaign: Transnational Islam and the Salafi madrasa in post-9/11 Indonesia". South East Asia Research. Taylor & Francis on behalf of the SOAS University of London. 18 (4): 675–705. doi:10.5367/sear.2010.0015. ISSN 2043-6874. JSTOR 23750964. S2CID 147114018.

- ^ "6 common misconceptions about Salafi Muslims in the West". OUPblog (in الإنجليزية). 2016-10-05. Retrieved 2021-08-20.

- ^ أ ب ت Kepel, Gilles (2006). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. p. 51. ISBN 9781845112578.

Well before the full emergence of Islamism in the 1970s, a growing constituency nicknamed `petro-Islam` included Wahhabi ulemas and Islamist intellectuals and promoted strict implementation of the sharia in the political, moral and cultural spheres; this proto-movement had few social concerns and even fewer revolutionary ones.

- ^ JASSER, ZUHDI. "STATEMENT OF ZUHDI JASSER, M.D., PRESIDENT, AMERICAN ISLAMIC FORUM FOR DEMOCRACY. 2013 ANTI–SEMITISM: A GROWING THREAT TO ALL FAITHS. HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES" (PDF). FEBRUARY 27, 2013. U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. p. 27. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

Lastly, the Saudis spent tens of billions of dollars throughout the world to pump Wahhabism or petro-Islam, a particularly virulent and militant version of supremacist Islamism.

- ^ أ ب Ayubi, Nazih N. (1995). Over-stating the Arab State: Politics and Society in the Middle East. I.B.Tauris. p. 232. ISBN 9780857715494.

The ideology of such regimes has been pejoratively labelled by some `petro-Islam.` This is mainly the ideology of Saudi Arabia but it is also echoed to one degree or another in most of the smaller Gulf countries. Petro-Islam proceeds from the premise that it is not merely an accident that oil is concentrated in the thinly populated Arabian countries rather than in the densely populated Nile Valley or the Fertile Crescent, and that this apparent irony of fate is indeed a grace and a blessing from God (ni'ma; baraka) that should be solemnly acknowledged and lived up to.

- ^ Mackey, Sandra (2002) [1987]. The Saudis: Inside the Desert Kingdom. W.W.Norton. p. 327. ISBN 9780393324174.

- ^ Ajami, Fouad (7 January 2007). "With Us or Against Us". New York Times.

before Petro-Islam and the Wahhabis blew in with new money and a new interpretation of the faith. The madrassas had not yet played havoc with the educational system.

- ^ أ ب ت Kepel, Gilles (2006). "Building Petro-Islam on the Ruins of Arab Nationalism". Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. p. 73. ISBN 9781845112578.

- ^ أ ب "'Petro-Islam' on the rise in Bangladesh". DW. 2011-06-20. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

"Many women have started wearing black Middle Eastern burqas, as it makes them feel 'safer'. [according to Imtiyaz Ahmed, a scholar and professor of International Relations at Dhaka University]

- ^ أ ب ت Abu-Rabi?, Ibrahim M. (1996). Intellectual Origins of Islamic Resurgence in the Modern Arab World. NY: SUNY Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780791426630.

[quoting Fouad Zakariyya ("a secular democratic thinker")]`A specific type of Islam has been gathering momentum of late, and the appropriate name that applies to it is `Petro-Islam.` The first and last goal of `Petro-Islam` has been to protect the petroleum wealth or, more correctly, the types of social relations underlying those [tribal] societies that possess the lion's share of this wealth. It is common knowledge that the principle of the `few dominating the largest portion of this wealth` permeates the social structure [of the Gulf region]. ... these petro-Islamites are exploiting the religious sensitivities of the masses for the purpose of `spreading a unique brand of Islam never seen before in history; the Islam of the veil, beard, and the Jilbab; the Islam that permits the stoppage of work during prayers' time, and prohibits women from driving automobiles.`

- ^ Hussain, Hamid (September 2004). "Politicization of Islam or Islamization of Politics: Saudi Arabian Experiment". Defense Journal of Pakistan. 8 (2): 104.

Saudis have used their resources; mainly cash to project itself as a major player in Muslim world. Fouad Ajami has named this phenomenon `Petro-Islam`. Large sums of money from public and private sources were distributed all around the globe to advance the muwwahhidin doctrine and pursue the country's foreign policy

- ^ أ ب Mackey, Sandra (2002) [1987]. The Saudis: Inside the Desert Kingdom. W.W.Norton. p. 327. ISBN 9780393324174.

The House of Saud believed that by coupling its image as the champion of Islam with its vast financial resources, petro-Islam could mobilize the approximately six hundred million Moslem faithful worldwide to defend Saudi Arabia against the real and perceived threats to its security and its rulers. Consequently, a whole panoply of devices was adopted to tie Islamic peoples to the fortunes of Saudi Arabia. The House of Saud has embraced the hajj... as a major symbol of the kingdom's commitment to the Islamic world.... These `guest of God` are the beneficiaries of the enormous sums of money and effort that Saudi Arabia expends on polishing it image among the faithful.... brought in heavy earth-moving equipment to level millions of square meters of hill peaks to accommodate pilgrims' tents, which were then equipped with electricity. One year the ministry had copious amounts of costly ice carted from Mecca to wherever the white-robed hajjis were performing their religious rites.

- ^ GWERTZMaAN, BERNARD (Oct 23, 1977). "Saudi Arabia, Mideast Power Broker". New York Times.

... the United States will again be underscoring the importance it attaches to Saudi Arabia's role as a power broker in the Middle East, the driving force that one Egyptian writer calls `Petro-Islam.` ... astute behind-the-scenes diplomatic activity has made Saudi Arabia a kind of fledgling power, not only in the Middle East, but further afield.

- ^ Al-Azm, Sadiq (14 September 2009). "The Fight over the Meaning of Islam". 14.09.2009. qantara.de. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

... "official state Islam". The most prominent form of this kind of Islam at present is the "petro-Islam" of countries like Saudi Arabia and Iran, fully funded and supported all over the world by abundant petro-dollars.

- ^ ʻAẓmah, ʻAzīz (1993). Islams and Modernities. Verso. p. 32.

Islamic discourse ... started in the 1950s and 1960s, as a local Arab purveyance of the Truman Doctrine, and was sustained initially by Egyptian and Syrian Islamists -- both earnest ones, and socially conservative, pro-Saudi business and other elements opposed to Nasserism and Baathism. This was indeed the first great cultural and ideological enterprise of Petro-Islam, along with ideas of pan-Islamism as a force counterbalancing Arab nationalism, and Islamic authenticity combating `alien` ideologies.

The Petro-Islamic enterprises has been hugely successful, especially with the substantial influx of the Arab intelligentsia to the relatively backward countries of the Arabian Peninsula, and the colossal ensemble of mediatic and other cultural organs that Petro-Islam has built up, and with which, most importantly, it has broken the secularist and nationalist cultural, mediatic and, to a lesser extent, the educational monopoly of the modern Arab state. - ^ Sengers, Gerda (2002). Women and Demons: Cultic Healing in Islamic Egypt. Brill. p. 240. ISBN 9004127712.

Migration can also have other consequences for the lives of women. In the oil states there is much stricter segregation and a much stricter code of moral behaviour than in Egypt. Many men who return to Egypt want to keep to the attitudes to women than hold sway in the oil states, and require their wives to take on the veil, give up their work outside the home and start to live a stricter `Islamic life`. In Egypt this is mockingly called `petro-Islam`.

- ^ Monshipouri, Mahmood (2009). Muslims in Global Politics: Identities, Interests, and Human Rights. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 86. ISBN 9780812202830.

The shari'a has been the primary target of attacks by the secularists [in Egypt]. Some of them deny its relevance to today's mundane affairs; others reject its divine origins; and still others argue that it can be interpreted in many different ways. A popular theory among secularists in Egypt, Azzam Tamimi writes, is that `Shari'a -- as understood by Islamic scholars and Islamic movements -- is alien to Egyptian society and is the product of Saudi influence on migrant Egyptian society.` Some experts have even referred to it as `petro-Islam` imported from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries.

- ^ (quoted in Lifting the Veil: The World of Muslim Women)Goodwin, Jan (1994). Price of Honour: Muslim Women Lift the Veil of Silence on the Islamic World. Warner Books.

Very few Muslim countries have given women their full rights, and both Islamic law and the message of Islam have been violated. But today, petro-Islam with its vast amounts of money is letting loose on the Islamic world a wave of fundamentalism. The movement, largely funded by the Saudis and Kuwaitis, is pushing a doctrine that is anti-women, anti-intellectual, anti-progress, and anti-science.

- ^ Jurisprudence and Law – Islam Reorienting the Veil, University of North Carolina (2009)

- ^ Daryl Champion (2002), The Paradoxical Kingdom: Saudi Arabia and the Momentum of Reform, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-12814-8, p. 23 footnote 7

- ^ source: Ian Skeet, OPEC: Twenty-Five Years of Prices and Politics (Cambridge: University Press, 1988)

- ^ Kepel, Gilles (2003). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B.Tauris. p. 75. ISBN 9781845112578.

- ^ quoted in a number of sources

- ^ Books quoting Kepel on Petro-Islam include A Choice of Enemies: America Confronts the Middle East By Sir Lawrence Freedman; Life among the Anthros and Other Essays By Clifford Geertz;

- ^ أ ب Kepel, Gilles (2003). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B.Tauris. p. 70. ISBN 9781845112578.

Prior to 1973, Islam was everywhere dominated by national or local traditions rooted in the piety of the common people, with clerics from the different schools of Sunni religious law established in all major regions of the Muslim world (Hanafite in the Turkish zones of South Asia, Malakite in Africa, Shafeite in Southeast Asia), along with their Shiite counterparts. This motley establishment held Saudi inspired puritanism in great suspicion on account of its sectarian character. However, after 1973, the oil-rich Wahhabites found themselves in a different economic position, being able to mount a wide-ranging campaign of proselytizing among the Sunnis. (The Shiites, whom the Sunnis considered heretics, remained outside the movement.) The objective was to bring Islam to the forefront of the international scene, to substitute it for the various discredited nationalist movements, and to refine the multitude of voices within the religion down to the single creed of the masters of Mecca. The Saudis' zeal now embraced the entire world... [and in the West] immigrant Muslim populations were their special target."

- ^ أ ب Kepel, Gilles (2003). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B.Tauris. p. 69. ISBN 9781845112578.

"The war of October 1973 was started by Egypt with the aim of avenging the humiliation of 1967 and restoring the lost legitimacy of the two states'... [Egypt and Syria] emerged with a symbolic victory... [but] the real victors in this war were the oil-exporting countries, above all Saudi Arabia. In addition to the embargo's political success, it had reduced the world supply of oil and sent the price per barrel soaring. In the aftermath of the war, the oil states abruptly found themselves with revenues gigantic enough to assure them a clear position of dominance within the Muslim world.

- ^ "The price of oil – in context". CBC News. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ^ Kepel, Gilles (2006). "Building Petro-Islam on the Ruins of Arab Nationalism". Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. pp. 61–2. ISBN 9781845112578.

"the financial clout of Saudi Arabia... had been amply demonstrated during the oil embargo against the United States, following the Arab-Israeli war of 1973. This show of international power, along with the nation's astronomical increase in wealth, allowed Saudi Arabia's puritanical, conservative Wahhabite faction to attain a preeminent position of strength in the global expression of Islam. Saudi Arabia's impact on Muslims throughout the world was less visible than that of Khomeini's Iran, but the effect was deeper and more enduring. The kingdom seized the initiative from progressive nationalism, which had dominated the 1960s, it reorganized the religious landscape by promoting those associations and ulemas who followed its lead, and then, by injecting substantial amounts of money into Islamic interests of all sorts, it won over many more converts. Above all, the Saudis raised a new standard -- the virtuous Islamic civilization -- as a foil for the corrupting influence of the West ...

- ^ Kepel, Gilles (2006). "Building Petro-Islam on the Ruins of Arab Nationalism". Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. p. 70. ISBN 9781845112578.

The propagation of the faith was not the only issue for the leaders in Riyadh. Religious obedience on the part of the Saudi population became the key to winning government subsidies, the kingdom's justification for its financial pre-eminence, and the best way to allay envy among impoverished co-religionists in Africa and Asia. By becoming the managers of a huge empire of charity and good works, the Saudi government sought to legitimize a prosperity it claimed was manna from heaven, blessing the peninsula where the Prophet Mohammed had received his Revelation. Thus, an otherwise fragile Saudi monarchy buttressed its power by projecting its obedient and charitable dimension internationally.

- ^ Gilles Kepel and Nazih N. Ayubi both use the term Petro-Islam, but others subscribe to this view as well, example: Sayeed, Khalid B. (1995). Western Dominance and Political Islam: Challenge and Response. SUNY Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780791422656.

- ^ Kepel describes Saudi control of the two holy cities as "an essential instrument of hegemony over Islam." Kepel, Gilles (2003). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B.Tauris. p. 75. ISBN 9781845112578.

- ^ أ ب Kepel, Gilles (2006). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. p. 72. ISBN 9781845112578.

founded in 1962 as a counterweight to Nasser's propaganda, opened new offices in every area of the world where Muslims lived. The league played a pioneering role in supporting Islamic associations, mosques, and investment plans for the future. In addition, the Saudi ministry for religious affairs printed and distributed millions of Korans free of charge, along with Wahhabite doctrinal texts, among the world's mosques, from the African plains to the rice paddies of Indonesia and the Muslim immigrant high-rise housing projects of European cities. For the first time in fourteen centuries, the same books .... could be found from one end of the Umma to the other... hewed to the same doctrinal line and excluded other currents of thought that had formerly been part of a more pluralistic Islam.

- ^ "'Petro-Islam' on the rise in Bangladesh". DW. 2011-06-20. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ "Shah Faisal Mosque". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ Kepel, Gilles (2006). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. p. 73. ISBN 9781845112578.

Tapping the financial circuits of the Gulf to finance a mosque usually began with private initiative. An adhoc association would prepare a dossier to justify a given investment, usually citing the need felt by locals for a spiritual center. They would then seek a `recommendation` (tazkiya) from the local office of the Muslim World League to a generous donor within the kingdom or one of the emirates. This procedure was much criticised over the years ... The Saudi leadership's hope was that these new mosques would produce new sympathizers for the Wahhabite persuasion.

- ^ أ ب ت Kepel, Gilles (2006). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. p. 72. ISBN 9781845112578.

For many of those returning from the El Dorado of oil, social ascent went hand in hand with an intensification of religious practice. In contrast to the bourgeois ladies of the preceding generation, who like to hear their servants address them as Madame .... her maid would call her hajja ... mosques, which were built in what was called the Pakistani `international style`, gleaming with marble and green neon lighting. This break with the local Islamic architectural traditions illustrates how Wahhabite doctrine achieved an international dimension in Muslim cities. A civic culture focused on reproducing ways of life that prevailed in the Gulf also surfaced in the form of shopping centers for veiled women, which imitated the malls of Saudi Arabia, where American-style consumerism co-existed with mandatory segregation of the sexes.

- ^ Kepel, Gilles (2006). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. p. 79. ISBN 9781845112578.

This first sphere [of Islamic banking] supplied a mechanism for the partial redistribution of oil revenues among the member states of OIC by way of the Islamic Development Bank, which opened for business in 1975. That strengthened Islamic cohesion and the increased dependence between the poorer member nations of African and Asia and the wealthy oil-exporting countries.

- ^ son of the assassinated King Faisal

- ^ Kepel, Gilles (2006). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. p. 79. ISBN 9781845112578.

- ^ أ ب

Kepel, Gilles (2003). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B.Tauris. pp. 70–1. ISBN 9781845112578.

Around 1975, young men with college degrees, along with experienced professors, artisans and country people, began to move en masse from the Sudan, Pakistan, India, Southeast Asia, Egypt, Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria to the Gulf states. These states harbored 1.2 million immigrants in 1975, of whom 60.5% were Arabs; this increased to 5.15 million by 1985, with 30.1% being Arabs and 43% (mostly Muslims) coming from the Indian subcontinent.... In Pakistan in 1983, the money sent home by Gulf emigrants amounted to $3 billion, compared with a total of $735 million given to the nation in foreign aid..... The underpaid petty functionary of yore could now drive back to his hometown at the wheel of a foreign car, build himself a house in a residential suburb, and settle down to invest his savings or engage in trade... he owed nothing to his home state, where he could never have earned enough to afford such luxuries.

- ^ Kepel, Gilles (2006). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. p. 71. ISBN 9781845112578.

- ^ examples include residential areas built to "house members of the devoutly Islamic business class who have returned from the Gulf," in Medinet Nasr district of Cairo; and Al Salam Shopping Centers Li-l Mouhaggabat that specialized in "providing shopping facilities for veiled women." (Kepel, Jihad, 2002, 385)

- ^ أ ب

Kepel, Gilles (2003). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B.Tauris. p. 63. ISBN 9781845112578.

[Arab "nationalists split into two fiercely opposed camps: progressives, led by Nasser's Egypt, Baathist Syria, and Iraq, versus the conservatives, led by the monarchies of Jordan and the Arabian peninsula. ...[in] the Six Day War of June 1967. ... It was the progressives, and above all Nasser, who had started the war and been most seriously humiliated militarily. [It] ... marked a major symbolic rupture.... Later on, conservative Saudis would call 1967 a form of divine punishment for forgetting religion. They would contrast that war, in which Egyptian soldiers went into battle shouting `Land! Sea! Air!` with the struggle of 1973, in which the same soldiers cried `Allah Akhbar!` and were consequently more successful. However it was interpreted, the 1967 defeat seriously undermined the ideological edifice of nationalism and created a vacuum to be filled a few years later by Qutb's Islamist philosophy, which until then had been confined to small circles of Muslim Brothers, prisoners,..."

- ^ Wright, Sacred Rage, (p.64-7)

- ^ Kepel, Gilles (2006). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. I.B. Tauris. p. 73. ISBN 9781845112578.

... a shift in the balance of power among Muslim states toward the oil-producing countries. Under Saudi influence, the notion of a worldwide `Islamic domain of shared meaning` transcending the nationalist divisions among Arabs, Turks, Africans, and Asians was created. All Muslims were offered a new identity that emphasized their religious commonality while downplaying differences of language, ethnicity, and nationality.

- ^ (writing in the New Yorker magazine and quoted by Indian lawyer Menaka Guruswamy, in an article in The Hindu newspaper which in turn was quoted by BBC Monitoring South Asia)

- ^ Guruswamy, Menaka (December 5, 2008). "Financing terror: the Lashkar and beyond". The Hindu. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

[Menaka Guruswamy, in an article "Financing Terror: the Lashkar and Beyond," published by Indian newspaper The Hindu, and quoted by BBC Monitoring South Asia [London] 05 Dec 2008.] According to The New Yorker's investigative journalist Seymour Hersh, the Saudi regime is "increasingly corrupt, alienated from the country's religious rank and file, and so weakened and frightened that it has brokered its future by channeling hundreds of millions of dollars in what amounts to protection money to fundamentalist groups that wish to overthrow it." This is a practice that has been referred to as "Petro-Islam."

- ^ (link has been messed with to prevent blocking) Zaidi, Syed Manzar Abbas (Spring 2010). "Tribalism, Islamism, Leadership and the Assabiyyas". Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies. 9 (25): 133-154 (145-6). Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ Joel Beinin; Joe Stork, eds. (1997). Political Islam: Essays from Middle East Report. I.B.Tauris. p. 9. ISBN 9781860640988.