أجاثياس

أگاثياس الدارس ( Agathias Scholasticus ؛ باليونانية: Ἀγαθίας σχολαστικός؛ ح. AD 530[1] – 582[1]/594) كان شاعراً يونانياً وكان المؤرخ الرئيسي لجزء من عهد الإمبراطور الروماني جستنيان الأول بين 552 و 558.

السيرة

Agathias was a native of Myrina (Mysia), an Aeolian city in western Asia Minor. His father was Memnonius. His mother was presumably Pericleia. A brother of Agathias is mentioned in primary sources, but his name has not survived. Their probable sister Eugenia is known by name. The Suda clarifies that Agathias was active in the reign of the Roman emperor Justinian I, mentioning him as a contemporary of Paul the Silentiary, Macedonius of Thessalonica and Tribonian.[2]

Agathias mentions being present in Alexandria as a law student at the time when an earthquake destroyed Berytus (Beirut).[1] The law school of Berytus had been recognized as one of the three official law schools of the empire (533). Within a few years, as the result of the disastrous earthquake of 551,[3][4][5] the students were transferred to Sidon.[6] The dating of the event to 551: as a law student, Agathias could be in his early twenties, which would place his birth to ح. 530.[1]

He mentions leaving Alexandria for Constantinople shortly following the earthquake. Agathias visited the island of Kos, where "he witnessed the devastation caused by the earthquake". At the fourth year of his legal studies, Agathias and fellow students Aemilianus, John and Rufinus are mentioned making a joint offering to Michael the Archangel at Sosthenium, where they prayed for a "prosperous future".[1]

He returned to Constantinople in 554 to finish his training, and practised as an advocatus (scholasticus) in the courts. John of Epiphania reports that Agathias practiced his profession in the capital. Evagrius Scholasticus and Nikephoros Kallistos Xanthopoulos describe Agathias as a rhetor ("public speaker"). The Suda and a passage of John of Nikiû call him "Agathias the scholastic".[1][7] He is known to have served as pater civitatis ("Father of the City", effectively a magistrate) of Smyrna. He is credited with constructing public latrines for the city. While Agathias mentions these buildings, he fails to mention his own role in constructing them.[1][8]

Myrina is known to have erected statues to honor Agathias, his father Memnonius, and Agathias' unnamed brother. He seems to have been known to his contemporaries more as an advocatus and a poet. There are few mentions of Agathias as a historian.[1]

Few details survive of his personal life – mainly in his extant poems. One of them tells the story of his pet cat eating his partridge. Another (Gr.Anth. 7.220) responds to his seeing the tomb of the courtesan Lais of Corinth, implying a visit to that city, which he refers to using the poetic name Ephyra. No full account of his life survives.[1]

الكتابات

Literature, however, was Agathias' favorite pursuit, and he remains best known as a poet. Of his Daphniaca, a collection of short poems in hexameter on 'love and romance' in nine books, only the introduction has survived.[1] But he also composed over a hundred epigrams, which he published together with epigrams by friends and contemporaries in a Cycle of New Epigrams or Cycle of Agathias, probably early in the reign of emperor Justin II (r. 565–578). This work largely survives in the Greek Anthology—the edition by Maximus Planudes preserves examples not found elsewhere.[1] Agathias's poems exhibit considerable taste and elegance.

He also wrote marginal notes on the Description of Greece (Ἑλλάδος περιήγησις) of Pausanias.

التواريخ

Almost equally valued are Agathias's Histories, which he started in the reign of Justin II. He explains his own motivation in writing it, as simply being unwilling to let "the momentous events of his own times" go unrecorded. He credits his friends with encouraging him to start this endeavor, particularly one Eutychianus.[1] This work in five books, On the Reign of Justinian, continues the history of Procopius, whose style it imitates, and is the chief authority for the period 552–558. It deals chiefly with the struggles of the Imperial army, under the command of general Narses, against the Goths, Vandals, Franks and Persians.[9]

The work survives, but seems incomplete. Passages of his history indicate that Agathias had planned to cover both the final years of Justin II and the fall of the Huns but the work in its known form includes neither. Menander Protector implies that Agathias died before having a chance to complete his history. The latest event mentioned in the Histories is the death of the Persian king Khosrau I (r. 531–579); which indicates that Agathias was still alive in the reign of Tiberius II Constantine (r. 578–582). The emperor Maurice (r. 582–602) is never mentioned, suggesting that Agathias was dead by 582.[1]

Menander Protector continued the history of Agathias, covering the period from 558 to 582. Evagrius Scholasticus alludes to Agathias' work, but he doesn't seem to have had access to the full History.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, Agathias's Histories "abound in philosophic reflection. He is able and reliable, though he gathered his information from eye-witnesses, and not, as Procopius, in the exercise of high military and political offices. He delights in depicting the manners, customs, and religion of the foreign peoples of whom he writes; the great disturbances of his time, earthquakes, plagues, famines, attract his attention, and he does not fail to insert "many incidental notices of cities, forts, and rivers, philosophers, and subordinate commanders." Many of his facts are not to be found elsewhere, and he has always been looked on as a valuable authority for the period he describes."

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, "The author prides himself on his honesty and impartiality, but he is lacking in judgment and knowledge of facts; the work, however, is valuable from the importance of the events of which it treats".[9]

Christian commentators note the superficiality of Agathias' Christianity: "There are reasons for doubting that he was a Christian, though it seems improbable that he could have been at that late date a genuine pagan" (Catholic Encyclopedia). "No overt pagan could expect a public career during the reign of Justinian, yet the depth and breadth of Agathias' culture was not Christian" (Kaldellis).

Agathias (Histories 2.31) is the only authority for the story of Justinian's closing of the re-founded Platonic (actually neoplatonic) Academy in Athens (529), which is sometimes cited as the closing date of "Antiquity".[10] The dispersed neo-Platonists, with as much of their library as could be transported, found temporary refuge in the Persian capital of Ctesiphon, and afterwards— under treaty guarantees of security that form a document in the history of freedom of thought— at Edessa, which just a century later became one of the places where Muslim thinkers encountered ancient Greek culture and took an interest in its science and medicine.

Agathias's Histories are also a source of information about pre-Islamic Iran, providing—in summary form—"our earliest substantial evidence for the Khvadhaynamagh tradition",[11] that later formed the basis of Ferdowsi's Shahname and provided much of the Iranian material for al-Tabari's History.

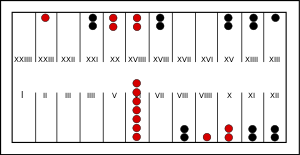

Agathias recorded the earliest description of the rules of backgammon, which he calls τάβλη (tabula) as it is still called in Greece, in a story relating an unlucky game played by the emperor Zeno. Zeno had a stack of seven checkers, three stacks of two checkers and two blots, checkers that stand alone on a point and are therefore in danger of being put outside the board by an incoming opponent checker. Zeno threw the three dice with which the game was played and obtained 2, 5 and 6. The white and black checkers were so distributed on the points that the only way to use all of the three results, as required by the game rules, was to break the three stacks of two checkers into blots, thus exposing them to capture and ruining the game for Zeno.[12][13]

نسخ وترجمات التواريخ

- Bonaventura Vulcanius (1594)

- Barthold G. Niebuhr, in Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae (Bonn, 1828)

- Jean P. Migne, in Patrologia Graeca, vol. 88 (Paris, 1860), col. 1248–1608 (based on Niebuhr's edition)

- Karl Wilhelm Dindorf, in Historici Graeci Minores, vol. 2 (Leipzig, 1871), pp. 132–453.

- R. Keydell, Agathiae Myrinaei Historiarum libri quinque in Corpus Fontium Historiae Byzantinae, vol. 2, Series Berolinensis, Walter de Gruyter, 1967

- S. Costanza, Agathiae Myrinaei Historiarum libri quinque (Universita degli Studi, Messina, 1969)

- J. D. Frendo, Agathias: The Histories in Corpus Fontium Historiae Byzantinae (English translation with introduction and short notes), vol. 2A, Series Berolinensis, Walter de Gruyter, 1975

- P. Maraval, Agathias, Histoires, Guerres et malheurs du temps sous Justinien (French), Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2007, ISBN 2-251339-50-7

- A. Alexakis, Ἀγαθίου Σχολαστικοῦ, Ἱστορίαι (in Greek) Athens, Kanakis Editions, 2008, ISBN 978-960-6736-02-5

المراجع

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش Martindale, Jones & Morris (1992), p. 23–25

- ^ Suda s.lem. Agathias (Alpha, 112: Ἀγαθίας)

- ^ Profile of Lebanon: History Archived يناير 28, 2011 at the Wayback Machine Lebanese Embassy of the U.S.

- ^ About Beirut and Downtown Beirut, DownTownBeirut.com. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ History of Phoenicia, fulltextarchive.com. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- ^ "Saida (Sidon)". Ikamalebanon.com. Archived from the original on 2009-06-28. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ Perseus.Tufts.edu, Rhetor, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, at Perseus

- ^ Sivan, H.S. (1989). "Town, country and province in Late Roman Gaul" (PDF). uni-koeln.de.

- ^ أ ب One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 1 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 370.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) This cites as authorities:- Editio princeps, by B. Vulcanius (1594)

- the Bonn Corpus Scriptorum Byz. Hist., by B. G. Niebuhr (1828)

- Migne, Patrologia Graeca, lxxxviii.

- L. Dindorf, Historici Graeci Minores (1871)

- W. S. Teuffel, "Agathias von Myrine," in Philologus (i. 1846)

- C. Krumbacher, Geschichte der byzantinischen Litteratur (2nd ed. 1897).

- ^ Hadas, Moses (1950). A History of Greek Literature. Columbia University Press. p. 273. ISBN 0-231-01767-7.

- ^ Averil Cameron, "Agathias on the Sasanians" in Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 23 (1969) p. 69.

- ^ أ ب Austin, Roland G. "Zeno's Game of τάβλη", The Journal of Hellenic Studies 54:2, 1934. p. 202-205.

- ^ Robert Charles Bell, Board and table games from many civilizations, Courier Dover Publications, 1979, ISBN 0-486-23855-5, p. 33–35.

للاستزادة

- A. Alexakis, "Two verses of Ovid liberally translated by Agathias of Myrina (Metamorphoses 8.877-878 and Historiae 2.3.7)", in Byzantinische Zeitschrift 101.2 (2008), pp. 609–616.

- A. Cameron, 'Agathias on the Sasanians', in Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 23 (1969) pp 67–183.

- A. Cameron, Agathias (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970). ISBN 0-19-814352-4.

- Chaumont, M.-L. (1984). "AGATHIAS". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume I/6: Afghanistan–Ahriman. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 608–609. ISBN 978-0-71009-095-9.

- A. Kaldellis, 'Things are not what they are: Agathias Mythistoricus and the last laugh of Classical', in Classical Quarterly, 53 (2003) pp 295–300.

- A. Kaldellis, 'The Historical and Religious Views of Agathias: A Reinterpretation', in Byzantion. Revue internationale, 69 (1999) pp 206–252.

- A. Kaldellis, 'Agathias on history and poetry', in Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 38 (1997), pp 295–306

- Martindale, John R.; Jones, A.H.M.; Morris, John (1992), The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Volume III: AD 527–641, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-20160-8, https://books.google.com/books?id=fBImqkpzQPsC

- W. S. Teuffel, 'Agathias von Myrine', in Philologus (1846)

- C. Krumbacher, Geschichte der byzantinischen Litteratur (2nd ed. 1897)

- S. Smith, Greek Epigram and Byzantine Culture: Gender, Desire, and Denial in the Age of Justinian (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

هذه المقالة تضم نصاً من مطبوعة هي الآن مشاع: هربرمان, تشارلز, ed. (1913). . الموسوعة الكاثوليكية. Robert Appleton Company.

هذه المقالة تضم نصاً من مطبوعة هي الآن مشاع: هربرمان, تشارلز, ed. (1913). . الموسوعة الكاثوليكية. Robert Appleton Company. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=,|coauthors=, and|month=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

وصلات خارجية

- قالب:Wikisourcelang-inline

- Poems by Agathias English translations

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Agathias

- Works by or about أجاثياس at Internet Archive

- Works by أجاثياس at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Agathias on the Persians: excerpts from History (English)

- Gerald Bechtle, Bryn Mawr Classical Review of Rainer Thiel, Simplikios und das Ende der neuplatonischen Schule in Athen, Stuttgart, 1999 (in English).

- Encyclopedia of Past Events

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Wikipedia articles incorporating text from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles containing فرنسية-language text

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- Articles incorporating text from the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia with Wikisource reference

- Ancient Greek poets

- Epigrammatists of the Greek Anthology

- Ancient Greek anthologists

- Ancient Greek historians

- Historians of Justinian I

- مواليد عقد 530

- 6th-century deaths

- Byzantine literature

- Byzantine poets

- 6th-century Greek poets

- 6th-century Byzantine historians

- Aeolians

- Greek-language historians from the Roman Empire

- 6th-century Byzantine writers