حرير العنكبوت

حرير العنكبوت، هي ألياف پروتينية تنسجها العناكب. تستخدم العناكب هذا الحرير لصنع الشباك التي تعمل كمصيدة لالتقاط فرائسها من الحيوانات الأخرى، أو كعش لحماية أبنائها. وأحيانا ما تعلق العناكب نفسها في تلك الشباك.

في بعض الأحيان، تستخدم العناكب هذا الحرير كطعام.[1][2]

وتم تطوير عدة طرق لجعل العناكب تزيد من نسجها للحرير.[3]

تعتمد جميع العناكب ـ بما فيها تلك التي لاتغزل نسيجًا ـ على خيوط الحرير بطرق كثيرة، بحيث يتعذر أن تعيش بدونها. وحيثما يذهب العنكبوت فإنه يغزل خيطاً من الحرير يُسمَّى خيط الجذب. ويسمى خيط الجذب هذا أيضًا خيط الحياة، وذلك لأنه يستعمله ـ غالباً ـ في الهروب من الأعداء.[4]

وإذا أحس العنكبوت بخطر يهدد نسيجه فإنه يهرب من النسيج بوساطة خيط الجذب ليختبئ بين الأعشاب، أو يبقى متعلقاً به في الهواء حتى يزول الخطر ثم يعود مرة أخرى إلى نسيجه عبر خيط الجذب.

وتستخدم العناكب الصيادة خيوط جذبها، لتتأرجح بها للوصول إلى الأرض من الأماكن العالية، وتستعمل أيضاً الحرير لغزل كتل صغير ة من الخيوط اللزجة تسمى أقراص الالتصاق تستعملها لتثبيت خيوط جذبها ونسيجها على العديد من الأسطح، وتبني أنواعٌ كثيرة من العناكب أعشاشاً من خيوط الحرير كمساكن لها، حيث يُبَطنُ بعضاً منها ورقة ُ نبات ملفوفةٌ بالحرير، ليجعل منها عُشًا له، بينما يحفر بعض منها جحورًا في الأرض يبطنها بالحرير، وتبني أنواعٌ أخرى أعشاشاً في وسط نسيجها.

يقوم كثير من العناكب غازلة النسيج بغزل حزم لزجة أو صفائح عريضة من خيوط الحرير أثناء الإمساك بالفريسة، بينما تحيط العناكب غازلة النسيج الدائري ضحاياها، بصفائح من الخيوط الحريرية، وكأنها مومياوات بحيث لاتستطيع الإفلات أبداً. وتغلف معظم إناث العناكب بيضها بما يُسمى كيس البيض الذي يُصنَّع من نوعٍ خاصٍ من خيوط الحرير.

التنوع الحيوية

الاستخدامات

All spiders produce silks and a single spider can produce up to seven different types of silk for different uses[5]. This is in contrast to insect silks, where most often only one type of silk is produced by an individual[6]. Over the 400 million years of evolution, spider silks may be used for a number of different ecological uses, each with properties to match the function of the silk (see Properties section). The evolution of spiders has lead to more complex and diverse uses of silk throughout its evolution, for example from primitive tube webs 300-400mya to complex orb webs 110mya[7].

| الاستخدام البيئي | مثال | المرجع |

|---|---|---|

| القبض على الفريسة | The orb webs produced by the Araneidae (typical orb-weavers); tube webs; tangle webs; sheet webs; lace webs, dome webs; single thread used by the Bolas spiders for ‘fishing’ | [7][5] |

| شل حركة الفريسة | Silk used a ‘swathing bands’ to wrap up prey. Often combined with immobilising prey using a venom. | [5] |

| التكاثر | Male spiders may produce sperm webs; spider eggs are covered in silk cocoons | [8][5] |

| Dispersal | ‘Ballooning’ used by many small spiders | [9] |

| مصدر للطعام | The kleptoparasitic Argyrodes eating the silk of host spider webs | [10] |

| بطانة للعش | Tube webs used by ‘primitive’ spider such as the European Tube Web Spider (Segestria florentina). Threads radiate out of nest to provide a sensory link to the outside. | [7] |

الأنواع

| الغدة | الاستخدام |

|---|---|

| Ampullate (Major) | Dragline silk - used for the web’s outer rim and spokes and the lifeline. |

| Ampullate (Minor) | Used for temporary scaffolding during web construction. |

| Flagelliform | Capture-spiral silk - used for the capturing lines of the web. |

| Tubuliform | Egg cocoon silk - used for protective egg sacs. |

| Aciniform | Used to wrap and secure freshly captured prey; used in the male sperm webs; used in stabilimenta |

| Aggregate | A silk glue of sticky globules |

| Piriform | Used to form bonds between separate threads for attachment points |

وتتكون خيوط العنكبوت الحريرية من بروتين يتم تصنيعه في غدد الحرير. ويوجد في العناكب سبعة أنواع من غدد الحرير، وعادة لايحتوي نوع واحد من العناكب على كل الأنواع السبعة مجتمعة. ويوجد في كل نوع من العناكب ـ على الأقل ـ ثلاثة أنواع من غدد الحرير، ولمعظم العناكب خمسة أنواع. وكل نوع من هذه الغدد ينتج نوعاً مختلفًا من الحرير. كما تنتج بعض غدد الحرير مادةً سائلة تتحول إلى مادة صلبة خارج الجسم، بينما ينتج بعضها حريرًا لاصقاً يبقى كذلك دون تغيير. ولايذوب حرير العنكبوت بالماء، وهو يعد من أقوى أنواع الألياف الطبيعية على الإطلاق.

وتعمل الغازلات التي تنسج الحرير، بطريقة تشبه عمل أصابع اليد ويستطيع العنكبوت إخراج وإدخال كل الغازلات وباستطاعته أيضًا أن يجمعها معاً. وبسبب امتلاك العنكبوت لغازلات مختلفة، فإنّ بإمكانه أن يجمع الحرير من الغدد المختلفة، وأن يصنع منها خيوطاً رفيعةً جداً، أو حزمة عريضةً وسميكة.

وبإمكان بعض أنواع العناكب غزل خيوط لزجة تشبه العقد المحبب حيث يقوم العنكبوت بنشر خيط جاف مُغطى بحرير لاصق بكميات كبيرة، ثم يطلقه بسرعة هائلة وهذه العملية تمكِّن الحرير اللاصق من تشكيل مجموعة من حبيبات دقيقة على طول الخيط. ويستخدم العنكبوت الخيوط المحببة في نسيج شراكه من أجل الإمساك بالحشرات الطائرة والقافزة.

ولبعض أنواع العناكب أعضاء غازلة أخرى تدعى الغريبلات وهي صفائح بيضية تستلقي بصورة مسطحة تقريًبا على منطقة البطن أمام الغازلات. وتمر عبرها مئات من الأنابيب الغازلة التي تنتج خيوط حرير دقيقة لزجة.

ويوجد لدى العناكب التي تمتلك غريبلات، صفٌ خاص من الشعيرات المقوَّسة يُدعى المشط الريشي على أرجلها الخلفية، يستعمله العنكبوت لغزل حرير جاف من الغازلات مع حرير لزج من الفريبل، مكوناً شريطاً منبسطاً من هذه الخيوط مجتمعة، يُسمى الحزمة الممشطة وتستعمل تلك العناكب الحزَمُ الممشطة في نسيجها مع ماتغزله من حرير آخر.

الخصائص

Spider silk is a remarkably strong material. Its tensile strength is comparable to that of high-grade steel (1500 MPa),[11][12] and about half as strong as aramid filaments, such as Twaron or Kevlar (3000 MPa).[13] Spider silk is about a fifth of the density of steel; a strand long enough to circle the Earth would weigh less than 500 grams (18 oz).[14]

Spider silk is also especially ductile, able to stretch up to 1.4 times its relaxed length without breaking; this gives it a very high toughness (or work to fracture), which "equals that of commercial polyaramid (aromatic nylon) filaments, which themselves are benchmarks of modern polymer fibre technology".[15][16] It can hold its strength below −40 °C.

The strongest known spider silk is produced by the species Darwin's bark spider (Caerostris darwini): "The toughness of forcibly silked fibers averages 350 MJ/m3, with some samples reaching 520 MJ/m3. ... Thus, C. darwini silk is more than twice as tough as any previously described silk, and over 10 times tougher than Kevlar."[17]

أنواع الحرير

| الحرير | الاستخدام |

|---|---|

| major-ampullate (dragline) silk | Used for the web's outer rim and spokes and the lifeline. Can be as strong per unit weight as steel, but much tougher. |

| capture-spiral silk | Used for the capturing lines of the web. Sticky, extremely stretchy and tough. |

| tubiliform (aka cylindriform) silk | Used for protective egg sacs. Stiffest silk. |

| aciniform silk | Used to wrap and secure freshly captured prey. Two to three times as tough as the other silks, including dragline. |

| minor-ampullate silk | Used for temporary scaffolding during web construction |

التركيب

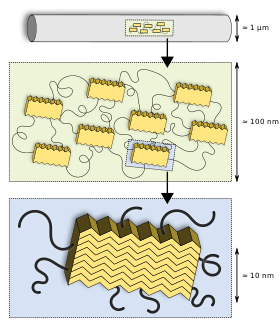

Although different species of spider, and different types of silk, have different protein sequences, a general trend in spider silk structure is a sequence of amino acids (usually alternating glycine and alanine, or alanine alone) that self-assemble into a beta sheet conformation. These "Ala rich" blocks are separated by segments of amino acids with bulky side-groups. The beta sheets stack to form crystals, whereas the other segments form amorphous domains. It is the interplay between the hard crystalline segments, and the strained elastic semi amorphous regions, that gives spider silk its extraordinary properties.[18]

[19]

The high toughness is due to the breaking of hydrogen bonds in these regions.

Various compounds other than protein are used to enhance the fiber's properties. Pyrrolidine has hygroscopic properties and helps to keep the thread moist. It occurs in especially high concentration in glue threads. Potassium hydrogen phosphate releases protons in aqueous solution, resulting in a pH of about 4, making the silk acidic and thus protecting it from fungi and bacteria that would otherwise digest the protein. Potassium nitrate is believed to prevent the protein from denaturing in the acidic milieu.[20]

التصنيع الحيوي

The unspun silk dope is pulled through silk glands, resulting in a transition from stored gel to final solid fiber.

The gland's visible, or external, part is termed the spinneret. Depending on the species, spiders will have two to eight spinnerets, usually in pairs. The beginning of the gland is rich in thiol and tyrosine groups. After this beginning process, the ampulla acts as a storage sac for the newly created fibers. From there, the spinning duct effectively removes water from the fiber and through fine channels also assists in its formation. Lipid secretions take place just at the end of the distal limb of the duct, and proceeds to the valve. The valve is believed to assist in rejoining broken fibers, acting much in the way of a helical pump.

The spinneret apparatus of a Araneus diadematus consists of the following glands:

- 500 Glandulae piriformes for attachment points

- 4 Glandulae ampullaceae for the web frame

- about 300 Glandulae aciniformes for the outer lining of egg sacs, and for ensnaring prey

- 4 Glandulae tubuliformes for egg sac silk

- 4 Glandulae aggregatae for glue

- 2 Glandulae coronatae for the thread of glue lines[20]

الاستخدامات البشرية

Peasants in the southern Carpathian Mountains used to cut up tubes built by Atypus and cover wounds with the inner lining. It reportedly facilitated healing, and even connected with the skin. This is believed to be due to antiseptic properties of spider silk[20] and because the silk is rich in vitamin K, which can be effective in clotting blood.[21]

Some fishermen in the Indo-Pacific ocean use the web of Nephila to catch small fish.[20]

The silk of Nephila clavipes has recently been used to help in mammalian neuronal regeneration.[22]

At one time, it was common to use spider silk as a thread for crosshairs in optical instruments such as telescopes, microscopes,[23] and telescopic rifle sights.[24]

Due to the difficulties in extracting and processing substantial amounts of spider silk, there is currently only one known piece of cloth made of spider silk, an 11-by-4-foot (3.4 by 1.2 m) textile with a golden tint made in Madagascar in 2009. 82 people worked for four years to collect over one million golden orb spiders and extract silk from them.[25]

حرير العنكبوت الصناعي

Spider silk is as strong as many industrial fibers (see tensile strength for common comparisons). There is commercial interest in duplicating spider silk artificially, since spiders use renewable materials as input and operate at room temperature, low pressures and using water as a solvent. However, it has been difficult to find a commercially viable process to mass-produce spider silk.

It is not possible to use spiders themselves to produce industrially useful quantities of spider silk, due to the difficulties of managing large quantities of spiders (although this was tried with Nephila silk[20]). Unlike silkworms, spiders eat one another, so spiders cannot be kept together.

The properties of silk are determined both by its chemical composition and the mechanical process by which it is produced.

The spider's highly sophisticated spinneret is instrumental in organizing the silk proteins into strong domains. The spinneret creates a gradient of protein concentration, pH, and pressure, which drive the protein solution through liquid crystalline phase transitions, ultimately generating the required silk structure, a mixture of crystalline and amorphous biopolymer regions. Replicating these complex conditions in a laboratory environment has proved difficult. Nexia used wet spinning and squeezed the silk protein solution through small extrusion holes in order to simulate the behavior of the spinneret, but this has so far not been sufficient to replicate the properties of native spider silk.[26]

One approach which does not involve farming spiders is to extract the spider silk gene and use other organisms to produce the spider silk. In 2000 Canadian biotechnology company Nexia successfully produced spider silk protein in transgenic goats which carried the gene for it; the milk produced by the goats contained significant quantities of the protein, 1–2 grams of silk proteins per liter of milk. Attempts to spin the protein into a fiber similar to natural spider silk resulted in fibers with tenacities of 2–3 grams per denier (see BioSteel).[27][28]

Extrusion of protein fibers in an aqueous environment is known as "wet-spinning". This process has so far produced silk fibers of diameters ranging from 10 to 60 μm, compared to diameters of 2.5–4 μm for natural spider silk.

In March 2010, researchers from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science & Technology (KAIST) have succeeded in making spider silk directly with the bacteria E.coli, modified with certain genes of the spider Nephila clavipes. This thus eliminates dependency on the spider for milking and allows to manufacture the spider silk at a more cost-effective manner.[29]

The company Kraig Biocraft Laboratories[30] has used research from the Universities of Wyoming and Notre Dame in a collaborative effort to create a silkworm that is genetically altered to produce spider silk. In September 2010 it was announced at a press conference at the University of Notre Dame that the effort had been successful.[31]

انظر أيضا

- شبكة العنكبوت

- Hagfish - منتج مشابه من الألياف.

- حرير – ألياف طبيعية تنتجها ديدان القز.

- "The Silk Spinners", a BBC program about silk-producing animals.

المصادر

- ^ "Spider Silk". School of Chemistry – Bristol University – UK. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ Miyashita, Tadashi (2004). "Silk feeding as an alternative foraging tactic in a kleptoparasitic spider under seasonally changing environments". Journal of Zoology. 262 (03): 225–229. doi:10.1017/S0952836903004540. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ An Apparatus and Technique for the Forcible Silking of Spiders

- ^ العنكبوت، الموسوعة المعرفية الشاملة

- ^ أ ب ت ث (Foelix 1996)Foelix, R. F. (1996). Series Editor (ed.). Biology of spiders. Oxford, N.Y: Oxford University Press. p. 330.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Sutherland, T., Young, J. & Weisman, S. (2009). "Insect Silk: One Name, Many Materials". Ann. Rev. Entomol. 55: 171–188. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085401.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب ت Hillyard, P. (2007). Series Editor (ed.). The Private Life of Spiders. London: New Holland. p. 160. ISBN 9781845376901.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ Nentwig, W. & Heimer, S. (1987). Wolfgang Nentwig (ed.). Ecological aspects of spider webs. Springer-Verlag. p. 211.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Flying Spiders over Texas! Coast to Coast. Chad B., Texas State University Undergrad Describes the mechanical kiting of spider "ballooning".

- ^ Miyashita, Tadashi (2004). "Silk feeding as an alternative foraging tactic in a kleptoparasitic spider under seasonally changing environments". Journal of Zoology. 262 (03): 225–229. doi:10.1017/S0952836903004540. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "SpringerLink -". www.springerlink.com. Retrieved 2010-08-18.

- ^ "Overview of materials for AISI 4000 Series Steel". www.matweb.com. Retrieved 2010-08-18.

- ^ "DuPont Kevlar 49 Aramid Fiber". www.matweb.com. Retrieved 2010-08-18.

- ^ Spider dragline silk has a tensile strength of roughly 1.3 GPa. The tensile strength listed for steel might be slightly higher – e.g. 1.65 GPa. [1]Shao, Z. Vollrath, F. (August 15, 2002). "Materials: Surprising strength of silkworm silk". Nature. 418 (6899): 741. doi:10.1038/418741a. PMID 12181556.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link), but spider silk is a much less dense material, so that a given weight of spider silk is five times as strong as the same weight of steel. - ^ Vollrath, F. Knight, D.P. (2001). "Liquid crystalline spinning of spider silk". Nature. 410 (6828): 541. doi:10.1038/35069000. PMID 11279484.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Spider Silk". www.chm.bris.ac.uk. Retrieved 2010-08-18.

- ^ Agnarsson I, Kuntner M, Blackledge TA (2010) Bioprospecting Finds the Toughest Biological Material: Extraordinary Silk from a Giant Riverine Orb Spider. PLoS ONE 5(9): e11234. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011234

- ^ Liu, Y., Sponner, A., Porter, D., Vollrath, F. (2008). "Proline and Processing of Spider Silks". Biomacromolecules. 9 (1): 116. doi:10.1021/bm700877g. PMID 18052126.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Papadopoulos, P., Ene, R., Weidner, I., Kremer, F. (2009). "Similarities in the Structural Organization of Major and Minor Ampullate Spider Silk". Macromol. Rapid Commun. 30: 851–857. doi:10.1002/marc.200900018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج Heimer, S. (1988). Wunderbare Welt der Spinnen. Urania. p.12 خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Heimer" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ Jackson, Robert R (1974). "Effects of D-Amphetamine Sulphate and Diasepam on Thread Connection Fine Structure in a Spider's Web" (PDF). North Carolina Department of Mental Health.

- ^ Allmeling, C., Jokuszies, A., Reimers, K., Kall, S., Vogt, P.M. (2006): Use of spider silk fibers as an innovative material in a biocompatible artificial nerve conduit. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 10(3):770–77 PDF – doi:10.2755/jcmm010.003.18

- ^ Berenbaum, May R., Field Notes – Spin Control, The Sciences, The New York Academy Of Sciences, September/October 1995

- ^ Example of use of spider silk for telescopic rifle sights

- ^ "1 Million Spiders Make Golden Silk for Rare Cloth".

- ^ Scheibel, T. (2004): Spider silks: recombinant synthesis, assembly, spinning, and engineering of synthetic proteins. "Microb Cell Fact" 3:14 [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ Spider silk made using bacteria

- ^ "Kraig Biocraft Laboratories".

- ^ "University of Notre Dame".

- Forbes, Peter (4th Estate, London 2005). The Gecko's Foot – Bio Inspiration: Engineered from Nature, ISBN 0-00-717990-1 in H/B.

- Graciela C. Candelas, José Cintron. "A spider fibroin and its synthesis", Journal of Experimental Zoology (1981), Department of Biology, University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras, Puerto Rico 00931.

وصلات خارجية

- The Silk Gland – A very nice breakdown of the silk gland, its parts and uses with images and drawings.

- Spiders in Space – NASA article and database information on the research of spiders in space.

- Israeli and German scientists created artificial silk using genetically engineered spider proteins – Article on IsraCast

- The mechanical design of spider silks: from fibroin sequence to mechanical function – Article on The Journal of Experimental Biology

- The Real Spider-Man – Article on forming Spider Silk Fibers from Caterpillars

- Genetic tweak boosts stiffness of spider silk

- Silk & Webs – The Arachnology Home Page

- Silk Research Group at Oxford University

- Finding Inspiration in Spider Silk Fibers

- Russian Scientists Created Industrial Technology of Spider Silk Fibers production

- TeachersTV programme on Spider Silk