پوليفيمس

The blinded Polyphemus seeks vengeance on Odysseus: Guido Reni's painting in the Capitoline Museums. | |

| المجموعة | Cyclops |

|---|---|

| الموئل | صقلية، إيطاليا |

پوليفيمس (Polyphemus ؛ /ˌpɒlɪˈfiːməs/; باليونانية: Πολύφημος Polyphēmos) هو عملاق بعين واحدة، ابن پوسايدون و ثوسا في الأساطير اليونانية, one of the Cyclopes described in Homer's Odyssey. His name means "abounding in songs and legends".[1] Polyphemus first appears as a savage man-eating giant in the ninth book of the Odyssey. Some later Classical writers link his name with the nymph Galatea and present him in a different light.

أوديسيوس وپوليفيمس

الروايات الكلاسيكية

In Homer's epic, Odysseus lands on the island of the Cyclops during his journey home from the Trojan War and, together with some of his men, enters a cave filled with provisions. When the giant Polyphemus returns home with his flocks, he blocks the entrance with a great stone and, scoffing at the usual custom of hospitality, eats two of the men. Next morning, the giant kills and eats two more and leaves the cave to graze his sheep.

After the giant returns in the evening and eats two more of the men, Odysseus offers Polyphemus some strong and undiluted wine given to him earlier on his journey. Drunk and unwary, the giant asks Odysseus his name, promising him a guest-gift if he answers. Odysseus tells him "Οὖτις", which means "nobody"[2] and Polyphemus promises to eat this "Nobody" last of all. With that, he falls into a drunken sleep. Odysseus had meanwhile hardened a wooden stake in the fire and drives it into Polyphemus' eye. When Polyphemus shouts for help from his fellow giants, saying that "Nobody" has hurt him, they think Polyphemus is being afflicted by divine power and recommend prayer as the answer.

In the morning, the blind Cyclops lets the sheep out to graze, feeling their backs to ensure that the men are not escaping. However, Odysseus and his men have tied themselves to the undersides of the animals and so get away. As he sails off with his men, Odysseus boastfully reveals his real name, an act of hubris that was to cause problems for him later. Polyphemus prays to his father, Poseidon, for revenge and casts huge rocks towards the ship, which Odysseus barely escapes.

The story reappears in later Classical literature. In Cyclops, the 5th century BC play by Euripides, a chorus of satyrs offers comic relief from the grisly story of how Polyphemus is punished for his impious behaviour in not respecting the rites of hospitality.[3] In his Latin epic, Virgil describes how Aeneas observes blind Polyphemus as he leads his flocks down to the sea. They have encountered Achaemenides, who re-tells the story of how Odysseus and his men escaped, leaving him behind. The giant is described as descending to the shore, using a "lopped pine tree" as a walking staff. Once Polyphemus reaches the sea, he washes his oozing, bloody eye socket and groans painfully. Achaemenides is taken aboard Aeneas’ vessel and they cast off with Polyphemus in chase. His great roar of frustration brings the rest of the Cyclopes down to the shore as Aeneas draws away in fear.[4]

Julien d'Huy speculates that the myth may be palaeolithic.[5] Elements of the story of Odysseus and Polyphemus are recognizable in the folklore of many other European groups. Wilhelm Grimm collected versions in Serbian, Romanian, Estonian, Finnish, Russian, and German.[6][7] Versions in Basque, Lappish, Lithuanian, Gascon, Syrian, and Celtic are also known.[7]

تمثيلات فنية

The vivid nature of the Polyphemus episode made it a favorite theme of ancient Greek painted pottery, on which the scenes most often illustrated are the blinding of the Cyclops and the ruse by which Odysseus and his men escape.[8] One such episode, on a vase featuring the hero carried beneath a sheep, was used on a 27 drachma Greek postage stamp in 1983.

پوليفيمس وگالاتيا

روايات أدبية

Although there are some earlier references to the story of the love of Polyphemus for the sea-nymph Galatea and her preference for the human shepherd Acis, the best known source is a lost play by Philoxenus of Cythera, of which a few fragments and several accounts are left. Dating from about 400 BC, it links the love story to the arrival of Odysseus and, according to ancient sources, had a witty contemporary subtext. Philoxenos had supposedly had an affair with the mistress of Dionysius I of Syracuse and as a consequence was condemned to work in the stone quarries. Here he is supposed to have composed The Cyclops, with the tyrant cast in the role of the giant, while the successful lovers are the poet and his Galatea.[9]

The happy ending to their story was well known in the centuries that followed and is attested in both literature and the arts. In the course of a 1st-century BC love elegy on the power of music, the Latin poet Propertius mentions as one example that "Even Galatea, it’s true, below wild Etna, wheeled her brine-wet horses, Polyphemus, to your songs."[10] The division of contrary elements, in other words, is brought into harmony.

That their conjunction was fruitful is brought out in a later Greek epic from the turn of the 5th century AD. In the course of his Dionysiaca, Nonnus gives an account of the wedding of Poseidon and Beroe, at which the Nereid "Galatea twangled a marriage dance and restlessly twirled in capering step, and she sang the marriage verses, for she had learnt well how to sing, being taught by Polyphemos with a shepherd’s syrinx."[11]

In one of the murals rescued from the site of Pompeii, Polyphemus is pictured seated on a rock with a cithara (rather than a syrinx) by his side, holding out a hand to receive a love letter from Galatea, which is carried by a winged Cupid riding on a dolphin.

In another fresco, also dating from the 1st century AD, the two stand locked in a naked embrace (see below). From their union came the ancestors of various wild and war-like races. According to some accounts, the Celts (Galati in Latin, Γάλλοi in Greek) were descended from their son Galatos.[12] Other sources credit them with three children, Celtus, Illyrius and Galas, from whom descend the Celts, the Illyrians and the Gauls respectively.

A different story appears in Ovid's Metamorphoses.[nb 1] At its start, the treatment of the story is an extended paraphrase of the two idylls of Theocritus.[13] But in the final passage, Polyphemus spies on the love-making of Acis and Galatea and jealously crushes Acis with a rock. Galatea, who had fled into her native element, returns and changes her dead lover into the spirit of the Sicilian river Acis. It was this account which was to have the greatest impact in later ages.

النسخ الأوروپية اللاحقة

الرسم والنحت

التصوير الفني لپوليفيمس

پوليفيمس و أوديسيوس

Flemish Jacob Jordaens' depiction of Odysseus escaping from the cave of Polyphemus (1635).

Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein's 1802 head and shoulders portrait of the giant (Landesmuseum Oldenburg).

Arnold Bocklin's painting of Polyphemus standing on rocks onshore and swinging one of them back as the men row desperately over a surging wave.

پوليفيمس وگالاتيا و Acis

Polyphemus hears of the arrival of Galatea, Fourth Style, 45–79 AD

A pastoral interpretation of the Acis and Galatea story is Nicholas Poussin's "Landscape with Polyphemus" (1649)

Jean-Baptiste van Loo's contribution to "The Triumph of Galatea" series.

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

- ^ Book XIII lines 738–897

المراجع

- ^ πολύ-φημος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ^ οὔτις and Οὖτις, Georg Autenrieth, A Homeric Dictionary, on Perseus

- ^ Translation online

- ^ Aeneid Book 3, lines 588–691

- ^ Julien d'Huy, Polyphemus (Aa. Th. 1137) A phylogenetic reconstruction of a prehistoric tale, New Comparative Mythology, 1, 2013.

- ^ Grimm, Wilhelm (1857). Die Sage von Polyphem (in German). Abhandlungen der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. pp. 1–30. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ أ ب Pausanias (1898). Frazer, Sir James George (ed.). Pausanias's Description of Greece. Vol. 5. Macmillan. p. 344.

- ^ Klaus Junker, Interpreting the Images of Greek Myths: An Introduction, Cambridge University 2011, p. 80

- ^ The introduction to Ovid's Metamorphoses XIII, Cambridge University 2000, pp. 35–36

- ^ Elegies 3.2, online translation by A.S. Kline

- ^ Online translation by W.H.D. Rouse, Loeb 1942, 43, lines 390–93

- ^ David Rankins, "The Celts through Classical eyes” in The Celtic World, London 2012, chapter 3

- ^ A.H.F. Griffin, "Unrequited Love: Polyphemus and Galatea in Ovid's Metamorphoses", Greece & Rome Second Series, Vol. 30.2 1983

وصلات خارجية

- Polyphemus and Galatea depicted in statues with a golden harpsichord by Michele Todini, Rome, 1675 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

أعمال فنية محددة مذكورة أعلاه

- Polyphemus standing at the top of a cliff, Jean-Léon Gérôme, 1902, at Wikipaintings

- "Odysseus Deriding Polyphemus", J.M.W. Turner, 1829, at Wikipaintings

- Galatea Acis e Polifemo, Pietro Dandini, c. 1630, at Art Value

- fresco, Giulio Romano, 1528, at Webalice

- Polyphemus with a massive club, Corneille Van Clève, 1681, at Web Gallery of Art

- "The Triumph of Galatea", Francois Perrier, at Web Gallery of Art

- "The Triumph of Galatea", Giovanni Lanfranco, Art Clon

- The giant spies on Galatea, Gustave Moreau, at Muian

- Polyphemus meditates, at French Government culture site

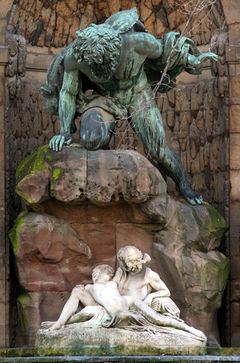

- statue of Polyphemus, Auguste Rodin, 1888, at French Government culture site

- A wrathful Polyphemus, Annibale Carracci, at Web Gallery of Art

- A wrathful Polyphemus, Lucas Auger, at French Government culture site

- A wrathful Polyphemus, Carle van Loo, at First Art Gallery

- A wrathful Polyphemus, Jean-Francois de Troy, 18th-century, at Tribes

أوپرات وأفلام مذكورة أعلاه