ديونيسياكا

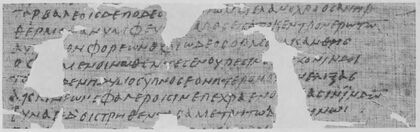

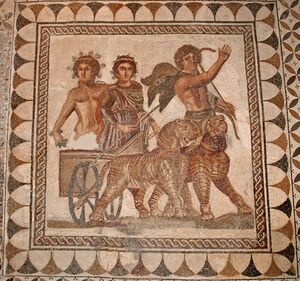

The Dionysiaca /ˌdaɪ.ə.nᵻˈzaɪ.ə.kə/ (باليونانية: Διονυσιακά, Dionysiaká) is an ancient Greek epic poem and the principal work of Nonnus. It is an epic in 48 books, the longest surviving poem from Greco-Roman antiquity at 20,426 lines, composed in Homeric dialect and dactylic hexameters, the main subject of which is the life of Dionysus, his expedition to India, and his triumphant return to the west.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Composition

The poem is thought to have been written in the 5th century AD. The suggestion that it is incomplete misses the significance of the birth of Dionysus' one son (Iacchus) in the final Book 48, quite apart from the fact that 48 is a key number as the number of books in the Iliad and Odyssey combined.[1] The older view that Nonnus wrote this poem before conversion to Christianity and the writing of his other long poem, a verse paraphrase of St John's Gospel, is now discredited, since a host of indications point to the latter being the earlier work and because it misses the eclecticism of late antique culture.[2] Editors have pointed out various inconsistencies and the difficulties of Book 39 which appears to be a disjointed series of descriptions, as evidence of lack of revision.[3]

Poetic models

The primary models for Nonnus are Homer and the Cyclic poets; Homeric language, metrics, episodes, and descriptive canons are central to the Dionysiaca. The influence of Euripides' Bacchae is also significant, as is probably the influence of the other tragedians whose Dionysiac plays do not survive. His debt to poets whose work survives only in disjointed fragments is far harder to gauge, but it is likely that he alludes to earlier poets' treatments of the life of Dionysus, such as the lost poems by Euphorion, Peisander of Laranda's elaborate encyclopedic mythological poem, Dionysius, and Soteirichus. Reflections of Hesiod's poetry, especially the Catalogue of Women, of Pindar, and Callimachus can all be seen in the work of Nonnus. Theocritus' influence can be detected in Nonnus' focus on pastoral themes. Finally, Virgil and especially Ovid seem to have influenced Nonnus' organization of the poem.[4]

Influence

Nonnus seems to have been an important influence for the poets of Late Antiquity, especially Musaeus, Colluthus, Christodorus, and Dracontius. He remained continuously important in the Byzantine world, and his influence can be found in Genesius and Planudes.[5] In the Renaissance, Poliziano popularized him to the West, and Goethe admired him in the 18th century. He was also admired by Thomas Love Peacock in 19th-century England.[6]

Metrics and style

The metrics of Nonnus have been widely admired by scholars for the poet's careful handling of dactylic hexameter and innovation.[7] While Homer has 32 varieties of hexameter lines, Nonnus only employs 9 variations, avoids elision, employs mostly weak caesurae, and follows a variety of euphonic and syllabic rules regarding word placement. It is especially remarkable that Nonnus was so exacting with meter because the quantitative meter of classical poetry was giving way in Nonnus' time to stressed meter. These metrical restraints encouraged the creation of new compounds, adjectives, and coined words, and Nonnus' work has some of the greatest variety of coinages in any Greek poem.

The poem is notably varied in its organization. Nonnus does not seem to arrange his poem in a linear chronology; rather, episodes are arranged by a loose chronological order and by topic, much as Ovid's Metamorphoses. The poem states as its guiding principle poikilia, diversity in narrative, form, and organization. The appearance of Proteus, a shapeshifting god, in the proem (preamble) serves as a metaphor for Nonnus' varied style.[8] Nonnus employs the style of the epyllion for many of his narrative sections, such as his treatment of Ampelus in 10–11, Nicaea in 15–16, and Beroe in 41–43. These epyllia are inserted into the general narrative framework and are some of the highlights of the poem. Nonnus also employs synkrisis, comparison, throughout his poem, most notably in the comparison of Dionysus and other heroes in Book 25. The complexity of organization and the richness of the language have caused the style of the poem to be termed Nonnian "Baroque."

Critical responses to the Dionysiaca

The size of Nonnus' poem and its late date between Imperial and Byzantine literature have caused the Dionysiaca to receive relatively little attention from scholars. The contributor to the Encyclopædia Britannica (8th edition, 1888), noting the poem's "vast and formless luxuriance, its beautiful but artificial versification, its delineation of action and passion to the entire neglect of character," remarked, "His chief merit consists in the systematic perfection to which he brought the Homeric hexameter. But the very correctness of the versification renders it monotonous. His influence on the vocabulary of his successors was likewise very considerable," expressing the 19th-century attitude to this poem as a pretty, artificial, and disorganized collection of stories. As with many other late classical poets, newer scholarship has avoided the value-laden judgments of 19th-century scholars and attempted to reassess and rehabilitate Nonnus' works. There are two main focuses of Nonnian scholarship today: mythology and structure.

Nonnus' compendious accounts of Dionysiac legend and his use of variant traditions and lost sources have encouraged scholars to use him as a channel to recover lost Hellenistic poetry and mythic traditions. The edition of Nonnus in the Loeb Classical Library includes a "mythological introduction" which charts the "decline" of Dionysiac mythology in the poem and implies that the work's only value is as a repository of lost mythology.[9] Nonnus remains an important source of mythology and information to those researching classical religion, Hellenistic poetry, and Late Antiquity. Recently, however, scholars have focused more positively on Nonnus' use of mythology within the poem as a way of talking about contemporary events,[10] as a way of playing with generic conventions,[11] and as a way of engaging with predecessors intertextually,[12] leading to an encouraging reassessment of his poetic and narrative style.

The unconventional structure of the Dionysiaca encouraged harsh criticism of the poem in scholarship. Robert Shorrock and Francois Vian have been at the forefront of reexamining the structure of the poem. Earlier scholars have looked to elaborate ring composition, a prophetic astrological program in the tablets of Harmonia, rhetorical encomium, or epyllion as structural concepts behind the poem to make sense of the unconventional narrative.[13] Others have felt that the style of the poem relies on dissonant juxtaposition for effect, using the so-called "jeweled style" of detailed narrative cameoes within a loose structure akin to Late Antique mosaics.[14] Vian has proposed looking at the poem's encyclopedic content as paralleling the full range of the Homeric cycle poetry.[15] Shorrock's contention is that the Dionysiaca employs a variety of narrative organizational principles and viewpoints, attempts to narrate all of classical mythology through the myths of Dionysus, and uses allegory and allusion to challenge his readers to draw meaning from his unconventional epic.[16]

Contents

Book 1 – The poem opens with the poet's invocation of the muses, his address to Proteus, and his commitment to sing the various episodes of Dionysus' life in a varied style (stylistic concept of ποικιλία, poikilia). The narrative starts with the origins of Dionysus: Zeus kidnaps Europa and her father orders Cadmus (Dionysus' maternal grandfather) to search for her. While Zeus is distracted making love to the maiden Pluto, the monster Typhon, following orders of his mother, the Earth, steals Zeus' weapons (the thunderbolts) and tries to dominate the world causing chaos and destruction wherever he goes. Zeus is now making love to Europa, but when he realises the dire situation calls Pan, Eros and Cadmus for help: Pan provides Cadmus with a pastoral disguise and he is supposed to charm Typhon with a pastoral song and Eros' help, while Zeus recovers his weapons. Typhon is so charmed by Cadmus' song that he promises him whatever he wants in exchange for it, not understanding that Cadmus is actually singing how he is defeated by Zeus.

Book 2 – Zeus steals the lightning from Typhon and takes Cadmus to a safe place. When Typhon notices the disappearance of Cadmus and of Zeus' weapons, he attacks the cosmos with all his poisons and the help of his animals. Chaos and destruction follow. During the night Zeus is encouraged to fight by Victory itself (Nike). The following morning Typhon challenges Zeus into combat and is defeated and killed by him after a long battle that affects the whole cosmos. While the earth repairs itself, Zeus promises to Cadmus the hand of Harmonia, daughter of Ares and Aphrodite, and bids him to found Thebes.

Book 3 – Cadmus' ship wanders the sea and stops at Samothrace, where Harmonia lives with her step-mother Electra and her step-brother Emathion. Joining them at their beautiful palace, he tells Electra of his lineage. Hermes bids Electra give her daughter Harmonia to be Cadmus' bride without a dowry.

Book 4 – Harmonia refuses to marry Cadmus because of his poverty, but Aphrodite takes the shape of Peisinoe, a girl of the neighbourhood, and produces a full encomium of Cadmus' beauty to convince her. Harmonia willingly leaves Samothrace with Cadmus who sails with her to Greece. Cadmus consults the oracle at Delphi and is told to follow a cow until she collapses and found there Thebes. There he slays Ares' dragon (thus attracting the god's anger onto himself), sows its teeth, and reaps the crop of sown-men.

Book 5 – Cadmus then founds Thebes, dedicating its seven doors to seven gods and planets. The gods attend to his wedding with Harmonia and enrich them with their gifts, of which the necklace given to her by Aphrodite receives particular attention. They have four daughters (Autonoe, Agaue, Ino and Semele) and a son (Polydorus). Cadmus gives Autonoe's hand to Aristaeus, well known as an inventor. They have a son, Actaeon, who becomes a passionate hunter. One day he sees Artemis bathing naked in a spring and is punished for it with his transformation into a stag which is then devoured by his dogs. Autonoe and Aristaeus search for his body but can only find it when the ghost of Actaeon appears to his father and tells him to find the bones of a stag and bury them. Agaue marries Echion and bears Pentheus to him. Ino marries Athamas, but Semele is reserved for Zeus, who is resenting the death of the first Dionysus (Zagreus), whom he had engendered with Persephone. Beginning of the story of Persephone: all the gods of the Olympus are madly in love with her.

Book 6 – Demeter, upset by Zeus's attention, goes to Astraeus, god of prophecy, who casts Persephone's horoscope, telling of her imminent rape by Zeus. Demeter conceals Persephone in a cave, but Zeus sleeps with her in the form of a snake, and she bears Zagreus. At Hera's bidding, the Titans kill Zagreus and chop him up. In anger, Zeus floods the world, causing havoc to the pastoral deities and the rivers.

Book 7 – Life on earth is miserable. Aion, god of time, begs Zeus to ease mortal life. Zeus predicts that the birth of Dionysus will change everything. Eros makes Zeus fall in love with Semele. The girl wakes up after a horrible nightmare predicting her death, consumed by the thunderbolt, and is told to sacrifice to Zeus to avert the omen. Spattered by the victim's blood she bathes naked in a river nearby, where Zeus spots her beauty and falls madly in love with her. That night Zeus joins Semele in her bed and metamorphoses into different animals during the courtship.

Book 8 – Semele becomes pregnant with Dionysus. Envy tells Hera of the deed and she disguises herself as an old woman the young girl trusts and tricks her into asking to see Zeus armed in full power with the lightning. She does and Zeus cannot say no to her. The fires of thunder burn Semele alive and Zeus immortalizes her.

Book 9 – Zeus rescues Dionysus from the fire and sews him into his thigh until he is ready to be born. Hermes receives baby Dionysus after birth and carries him to the daughters of Lamos, river nymphs, until Hera drives them mad. Hermes then gives the boy to Ino and she places him under the care of her attendant Mystis, who teaches him the rites of the mysteries. Hera finds out the whereabouts of Dionysus, but Hermes reaches him before she does and transfers him to the care of Rhea. Dionysus grows up in the mountains of Lydia where he learns to hunt and to dominate beasts. His early pursuits make his mother Semele proud. In the meantime a mad Ino wanders in the hills until Apollo takes pity on her and restores her sanity. Ino's household mourns for her disappearance, while his husband Athamas marries Themisto.

Book 10 – Themisto goes mad and kills her son. Athamas goes mad too and slaughters his son Learchos. Ino arrives when he is about to kill their son Melicertes whom she saves by jumping into the sea, becoming divinized. Meanwhile, Dionysus has become a teenager and lives in Lydia with a court of Satyrs. He falls in love for the first time with one of them, Ampelus (Vine). His passion for the boy is only spoiled by the knowledge that he will soon die, just as all the young lovers of the gods do. Dionysus and Ampelos indulge in a series of sports contests, the god allowing the boy to win.

Book 11 – Dionysus organizes a swimming contest and allows Ampelus to win. Ampelus is elated by his success and dresses up as a Bacchante as a form of celebration. Dionysus warns the boy to stay close to him, just in case a deity is jealous of their happiness and tries to kill him. A portent tells Dionysus that Ampelus will die and become a vine. Ate (Delusion) makes Ampelus jealous reminding him that Dionysus and the gods usually give their friends a special present, a special mount, and suggests that he should make a bull his own. Deluded, Ampelus rides a bull and provokes Selene by saying that he is a better bull-rider than her. Selene sends a gadfly to sting the bull. The animal starts kicking and Ampelus falls on his head on the ground. A satyr brings Dionysus the ill news. Dionysus prepares the body for the funeral and makes a long lament. Eros tries to console and distract him with the story of Calamos and Carpos, two handsome youngsters who were in love with each other. During a swimming contest Carpos drowns and Calamos, incapable of living without him, commits suicide. Calamos becomes the reeds of the river and Carpos the fruit of the earth. Dionysus is comforted with the story but mourning does not leave him. In the meantime the Seasons visit the house of Helios, the Sun.

Book 12 – Autumn enquires when the vine will appear on earth and become her personal attribute. Description of the tablets of Phanes, on which all the oracles of the future are engraved. Prediction of the metamorphosis of Ampelus into a vine. In the meantime, Dionysus mourns for Ampelus. Ampelus is transformed into the vine and Dionysus makes wine for the first time, reflecting on how Ampelus has escaped death. Dionysus adopts the vine as his personal attribute and claims to be superior to the other gods, because no other plant is so beautiful and provides so much merriment to humankind. Insertion of a second legend on the origins of the vine: it was growing wild and unknown of until Dionysus saw a snake suckling the juice from the grapes; Dionysus and his satyrs build the first wine press, make wine for the first time and have the first feast of the harvest, completely inebriated.

Book 13 – Zeus sends Iris to the halls of Rhea, ordering Dionysus to make a war against the impious Indians if he wants to join the gods on Olympus. Rhea gathers the troops for Dionysus. Catalogue of heroic troops including seven contingents from Greece and seven peripheral contingents.

Book 14 – Catalogue of semi-divine troops, also gathered by Rhea for Dionysus. Dionysus sets his army in motion until they encounter the first Indian contingent, led by Astraeis. Hera deludes Astraeis to go to battle against the Bacchic troops. Maenads and satyrs massacre the Indian troops until Dionysus takes pity on them and turns the waters of the neighbouring lake Astacid. The Indians try wine for the first time.

Book 15 – The Indians become drunk, fall asleep and are bound by the Dionysiac troops. Story of the virgin nymph Nicaea, who lives near the lake Astacid, enjoys hunting and refuses to behave like a woman. The shepherd Hymnus (a personification of the pastoral song) falls in love with her and courts her. Nicaea refuses even to listen to him and the boy becomes so desperate that he even asks her to kill him (a frequent line in the speeches of unrequited lovers). Nicaea takes the line literally and shoots him dead. The nature and its gods lament the dead shepherd and call for revenge.

Book 16 – Eros inspires in Dionysus a mad desire for Nicaea. Dionysus woos her and offers her a number of gifts, which she despises. After a day hunting, Nicaea drinks from a river whose waters are turned into wine, following Dionysus' earlier intervention in the first battle against the Indians. Inebriated, Nicaea falls asleep and is raped by the god as a punishment for killing Hymnus. Dionysus abandons her and when she wakes up she realises that she has been raped. She tries to find her rapist but soon she realises that she is pregnant and gives birth to Telete ('Initiation'). Dionysus founds the city of Nicaea, as a double commemoration of the namesake nymph and of his first battle against the Indians.

Book 17 – Dionysus travels through the east and is entertained by a shepherd, Brongus, in a country fashion. In thanks for his hospitality, Dionysus gives him some wine and teaches him how to grow and harvest the vine. Astraeis informs Orontes, son-in-law of the Indian king Deriades, of the defeat of the Indian army and the ruse of the waters turned into wine. Orontes is furious and harangues his troops not to fear the effeminate Dionysus and his army of women. The Indians charge in and at first seem to win, but Dionysus screams like nine thousand men and detains them. Orontes and Dionysus engage in single combat: a tap of a vine cluster on Orontes' chest is enough to split his armour. Orontes plunges his sword into his own belly and throws himself into the river nearby, giving it his name (Orontes river). The Bacchic troops massacre the Indians. Astraeis flees.

Book 18 – Dionysus arrives in Assyria, where the king Staphylus ("Cluster of grapes"), his wife Methe ("Drunkenness) and his son Botrys ("Grapes") entertain him in their marvelous palace in a drunken celebration. During his night with them he dreams that the wild king Lycurgus attacks him like a lion attacks a deer. The next morning Staphylus gives Dionysus splendid presents and encourages him to fight. While Dionysus is busy filling Assyria with his vine, Staphylus suddenly dies and his palace is filled with mourning voices. Dionysus returns to the palace only to find his friend dead.

Book 19 – Dionysus consoles Methe and Botrys giving them wine and hosts the funeral games for Staphylus, with contests of singing and pantomime.

Book 20 – The end of the games brings the mourning to an end. In a dream, Eris drives Dionysus to war. Methe, Botrys and their servant Pithos ("Wine-jar") join the Bacchic forces. They arrive in Arabia, where king Lycurgus has been stirred to fight by Hera. At the same time Hera deludes Dionysus with a false dream, in which Hermes counsels Dionysus to approach Lycurgus peaceably and without weapons. Lycurgus attacks Dionysus and the Bacchantes with a massive pole-axe. Dionysus jumps into the sea where he is entertained and consoled by Nereus. In his warlike paroxysm Lycurgus even attacks the sea and provokes the gods.

Book 21 – Lycurgus attacks the Bacchantes a second time, in particular Ambrosia who is metamorphosed into a vine and suffocates Lycurgus with its shoots, while the Bacchantes throng to kill him. Poseidon causes an earthquake, but Hera saves him temporarily until Zeus punishes him turning him into a blind wanderer. While Dionysus is entertained in the halls of Nereus, the Bacchic army is dispirited. The satyr Pherespondos arrives at the court of the Indian king Deriades and gives him Dionysus' message: he should accept the cult of the vine or face him in battle. Deriades, a son of the river (Jhelum River) dismisses Dionysus' offer of peace. Dionysus leaves the bottom of the sea, joins his troops and prepares for battle.

Book 22 – The Bacchic troops arrive at the river Hydaspes, where the trees and animals receive Dionysus with joy. The Indians see the miracles performed by Dionysus and are tempted to surrender, but Hera deceives their leader Thureus. The Indians try to ambush the Bacchic troops but a nymph warns Dionysus of the impending peril. In the battle Oeagrus, Aeacus, and Erectheus all distinguish themselves.

Book 23 – Dionysus and Aeacus fight the Indians in the river, where most of them drown. Hera encourages the Hydaspes to drown the Bacchic troops as they cross the river. The Bacchic army starts to cross the Hydaspes using strange means of navigation. The Hydaspes is upset because his waters are fouled with blood and dead bodies and because of how easily the Bacchic troops cross it. He tries to drown them in a flood. Dionysus responds angrily to the threat and sets the river banks on fire. The survival of the vegetation, fish and river nymphs is under threat. Hydaspes asks Tethys to help him.

Book 24 – Zeus and Hera stay the anger of the contenders. Hydaspes surrenders and Dionysus draws back his torch. The Bacchic army finishes crossing the river only to find that Deriades has placed his troops on the other bank of the river. The gods come down from the Olympus to save their protégés and the army settles in the hills nearby. Thureus tells the Indian king Deriades of what has happened. The news of the defeat reaches the Indian people and their morale deteriorates. In the forest, the Bacchic troops celebrate their victory. Leucus sings the story of Aphrodite's weaving contest with Athena and her defeat.

Book 25 – The poet invokes the Muse in his second proem, saying that in emulation of Homer he will skip over the first six years of the war. Comparison of Dionysus' deeds with those of Perseus, Minos, and Heracles, concluding that Dionysus is better than the heroes. Return to the main narrative: the Ganges, Deriades and the Indian people are scared by a number of Bacchic miracles. Dionysus is angry because Hera is delaying his victory. Rhea sends Attis to visit Dionysus and give him a shield that will protect him in battle and promises that he will conquer the city of the Indians in the seventh year of the war. Description of the shield, covered with constellations and adorned with a number of scenes: foundation of Thebes, Ganymede and Zeus and the Lydian myth of Tylos.

Book 26 – Athena drives Deriades to gather his allies. Catalogue of Indian troops: fourteen contingents from the Indus valley and the eastern areas of the Median empire. Descriptions rich in ethnographic material.

Book 27 – Deriades exhorts his troops to attack Dionysus near the mouth of the Indus. Dionysus places his battalions carefully and harangues his troops. In the meantime, in the Olympus, Zeus encourages Apollo and Athena to join their brother Dionysus and also addresses the gods who back the Indian side (Hera and Hephaestus).

Book 28 – The battle rages. Exploits and deaths of Phaleneus, Dexiochus and Clytios. Exploits of Corymbasos. Strange deaths in battle. Exploits of the Cyclopes and Korybantes.

Book 29 – Exploits of Dionysus' lover, Hymenaeus, who is wounded by an Indian arrow and healed by Dionysus. Exploits of the Dionysiac troops, especially Aristeus, the Kabeiri and the Korybantes. Offensive of the Bacchantes, wounded by the Indians and healed by Dionysus. The battle comes to a halt with the arrival of night. Rhea sends Ares a deceitful dream: he should abandon the battle because Hephaestus is about to seduce Aphrodite. Ares leaves at once.

Book 30 – Exploits of Morrheus, Deriades' son-in-law. Tectaphus is slain by Eurymedon (one of the Cabiri, children of Hephaestus and Cabiro). Hera encourages Deriades to fight and Dionysus is about to flee, but Athena stops him. Dionysus goes back to battle and massacres the Indian troops.

Book 31 – Hera goes to Persephone and tricks her into lending her the services of a Fury, Megaira, whom she instructs to madden Dionysus. Hera also instructs Iris to persuade Hypnus to cause Zeus to sleep, claiming that as god of nocturnal revels, Dionysus is his natural enemy, and that he should not risk angering Hera, the mother of his beloved Pasithea. Hera borrows Aphrodite's girdle, the cestus, in order to seduce Zeus.

Book 32 – Hera charms Zeus with the girdle, they make love, and while Zeus sleeps Megaira drives Dionysus mad. In the absence of Dionysus, Deriades and Morrheus rout the Bacchantes. The Bacchic army panics.

Book 33 – A Grace tells Aphrodite about Dionysus' madness and of how Morrheus is pursuing the Bacchante Chalcomede. Aphrodite sends Aglaia to fetch Eros, who is playing kottabos with Hymenaeus. In exchange for a chaplet made by Hephaestus, Eros agrees to cause Morrheus to fall in love with Chalcomede. Shaken by lovesickness Morrheus loses interest in battle and pursues Chalcomede, who makes him think that she reciprocates his feelings. Morrheus' lovesickness becomes more acute during the night. Chalcomede fears for her virginity but is comforted by Thetis, who asks her to delude Morrheus and promises that a serpent will protect her virginity.

Book 34 – Morrheus wanders on his own during the night and his servant Hyssacos recognises the signs of love and comforts him. Beginning of a new day: Morrheus nourishes his hope of love, while the Bacchic troops are completely dispirited in the absence of Dionysus. Morrheus attacks the Bacchantes and takes some captives as a gift for Deriades, who sends them to be tortured and killed in various ways. Chalcomede lures Morrheus out of the battle. Deriades drives the Bacchantes inside the city walls.

Book 35 – The Indians slay the Bacchantes in the city. Chalcomede lures Morrheus away from the battle making him believe that she is in love with him. When he is about to rape her the serpent that protects her virginity attacks him. In the meantime Hermes lets the Bacchantes out of the city. Zeus awakens and forces Hera to cure Dionysus' madness by breastfeeding him (a sign of adoption) and anointing him with ambrosia. Dionysus rejoins his army.

Book 36 – Confrontation of pro-Dionysiac and pro-Indian divinities in the Olympus: Athena defeats Ares, Hera defeats Artemis, Apollo confronts Poseidon, but Hermes pacifies them. On earth, Deriades harangues his troops and charges with his elephants. After a series of combats and descriptions of carnage, Deriades fights one-on-one with Dionysus: Dionysus eludes him adopting different shapes, imprisons him with the tendrils of a vine and finally releases him. Dionysus orders the Rhadamanes to build a fleet for him. Deriades presides the Indian assembly, in which he harangues his troops for the sea-battle. The two armies sign a truce to bury the dead.

Book 37 – Dionysus builds the pyre for Opheltes and celebrates funeral games, including a chariot race, pugilism, wrestling, foot race, discus, archery and javelin throw.

Book 38 – Two omens foretell Dionysus' victory, first a solar eclipse and then an eagle (i.e. Dionysus) throwing a serpent (i.e. Deriades) to the river. The first of them is interpreted by the seer Idmon, the second by Hermes, who tells at length the story of Phaethon from his genealogy to his death and catasterism.

Book 39 – The sea-battle begins on the arrival of Dionysus' brand-new fleet. Deriades and Dionysus harangue their troops, and Aeacus and Erechtheus ask the gods for help. The narrative of the battle is dominated by descriptions of carnage until the Indians are routed by a burning ship sent into their line. Deriades flees.

Book 40 – Deriades returns to battle and is confronted by Dionysus who grazes him with his thyrsus and forces him to jump into the river Hydaspes, calling the war to an end. Deriades' wife (Orsiboe) and daughters (Cheirobie and Protonoe) mourn him. Dionysus buries the dead, celebrates his victory and distributes spoils. Modaeus is appointed as governor of India. Dionysus travels to Tyre, admires the city, and hears the story of its founding from Heracles.

Book 41 – This book describes the mythical history of the city of Beroe (Beirut). The poet tells the story of the nymph Beroe, daughter of Aphrodite. He describes her birth and her maturation. Aphrodite goes to Harmonia to find out the destiny of Beirut, and she prophesies its future prosperity in the Roman Empire under Augustus.

Book 42 – Dionysus and Poseidon both fall in love with Beroe. Dionysus pursues her through the forests in love, meeting with Pan, and wooing the nymph with demonstrations of his abilities. Dionysus and Poseidon decide to fight over the girl.

Book 43 – The army of Poseidon's sea gods and the army of Dionysus battle each other. Zeus gives Beroe's hand to Poseidon who consoles Dionysus.

Book 44 – Dionysus arrives at Thebes and Pentheus refuses his rites and arrests Dionysus. The Furies attack Pentheus' palace and Agave and her sisters are driven mad.

Book 45 – Teiresias and Cadmus try to propitiate Dionysus but Pentheus attacks the god who tells him the story of the Tyrsenian pirates. Pentheus imprisons Dionysus, but the god destroys the palace and escapes.

Book 46 – Dionysus tricks Pentheus into spying on his mother and her sisters in their frenzy and is killed by them.

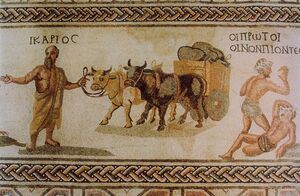

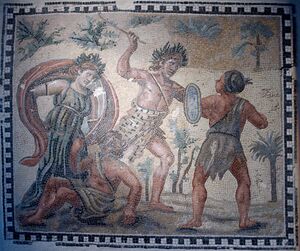

Book 47 – The thiasus arrives at Athens and the city rejoices. Dionysus teaches Icarius viticulture, and the farmer gives his neighbors wine. When they are drunk they kill Icarius. His daughter Erigone, informed by a dream, finds her dead father and hangs herself, but is then made into a constellation by Zeus. Ariadne bewails her abandonment by Theseus and Dionysus weds her. Dionysus drives the women of Argos to kill their children for refusing his rites. Perseus is incited by Hera to attack the Bacchantes and turns Ariadne into stone after which the Argives accept the rites of Dionysus on Hermes' demand.

Book 48 – Hera prays to Gaia, who stirs her sons the Giants to fight Dionysus and they are slain. Dionysus wrestles with the daughter of King Sithon to win her hand and then slays the king when he wins. Dionysus goes to Asia Minor where he meets the nymph Aura. Aura vies with Artemis in a beauty contest, and Artemis, in spite, has Nemesis make Dionysus fall in love with Aura and pursue her. Ariadne appears to Dionysus in a dream and complains that he has forgotten her. Dionysus rapes Aura as she sleeps; when she awakes she goes mad and slaughters shepherds and destroys a shrine of Aphrodite. Artemis mocks the pregnant Aura as Nicaea helps her give birth to the twins after whom Mt. Dindymon is named. Aura tries to get a lion to eat the children, but they are saved and she is transformed into a spring. One of the children, Iacchus is given to Athena, Ariadne's crown is made a constellation, and Dionysus is enthroned on Olympus.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Translations and editions

- Nonnus: Tales of Dionysus, translated by Stanley Lombardo, William Levitan and others (2022) University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-47213-311-6

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca, Volume I: Books 1–15, translated by W. H. D. Rouse, Loeb Classical Library No. 344, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1940 (revised 1984). ISBN 978-0-674-99379-2.Online version at Harvard University Press. Internet Archive (1940). Dionysiaca, Volume II: Books 16–35, translated by W. H. D. Rouse, Loeb Classical Library No. 345, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1940. ISBN 978-0-674-99391-4. Online version at Harvard University Press. Internet Archive (1940). Dionysiaca, Volume III: Books 36–48, translated by W. H. D. Rouse, Loeb Classical Library No. 346, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd., 1940. ISBN 978-0-674-99393-8. Online version at Harvard University Press. Internet Archive (1940, reprinted 1942).

- Koechly, Arminius, Nonni panopolitani dionysiacorum, Volume I, Bibliotheca Teubneriana, Leipzig, Teubner, 1857. Online version at the Munich Digitization Center. Volume II, Bibliotheca Teubneriana, Leipzig, Teubner, 1858. Online version at the Munich Digitization Center.

Footnotes

- ^ Hopkinson, N. Studies in the Dionysiaca of Nonnus (Cambridge, 1994) pp.1–4.

- ^ Nonnus is conclusively demonstrated to have been Christian during the composition of Dionysiaca by F. Vian, in REG 110 (1997), pp 143–60.

- ^ Hopkinson, pg.3

- ^ S. Fornaro, s.v. "Nonnus", in Brill's New Pauly vol. 9 (ed. Canick & Schneider) (Leiden, 2006) col.812–815, col. 814.

- ^ Shorrock, R. The Challenge of Epic: Allusive Engagement in the Dionysiaca of Nonnus (Leiden, 2001) pp.1–2

- ^ Lind, L. "Nonnus and his Readers" in RPL 1.159–170

- ^ See Fornaro, col.813–814

- ^ Fornaro, col.813 and Shorrock, pg.20ff.

- ^ Rose, H. J. Nonnus' Dionysiaca (London, 1940) pp.x–xix

- ^ Chuvin, P. "Local Traditions and Classical Mythology in Nonnus' Dionysiaca in ed. Hopkinson, N. Studies in the Dionysiaca of Nonnus (Cambridge, 1994) pg.167ff.

- ^ Harries, B. The Pastoral Mode in the Dionysiaca in ed. Hopkinson, N. Studies in the Dionysiaca of Nonnus (Cambridge, 1994) pg.63ff

- ^ Hopkinson, N. "Nonnus and Homer" and Hollis, A. "Nonnus and Hellenistic Poetry" in ed. Hopkinson, N. Studies in the Dionysiaca of Nonnus (Cambridge, 1994) pg.9ff. and 43ff.

- ^ Shorrock, pp.10–17

- ^ Shorrock, pp.17–19

- ^ Shorrock, pg.26

- ^ Shorrock, pg.23

External links

- Raw OCR of Köchly's Teubner edition (1857) at the Lace collection of Mount Allison University: vol. 1 Archived 2018-08-24 at the Wayback Machine and vol. 2 Archived 2018-08-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- R.F. Newbold summarizes his work on Dionysiaca

- Full English translation of Dionysiaca on perseus catalog