أشباه الطيور

| أشباه الطيور Paravians | |

|---|---|

| |

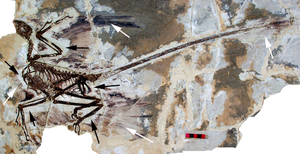

| عينات أحفورية من Microraptor | |

| |

| توراكو أحمر العرف في حديقة حيوان سان دييگو | |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| أصنوفة غير معروفة (أصلحها): | الحياة |

| مملكة: | الحيوانية |

| Phylum: | حبليات |

| فرع حيوي: | وحوش قدمية |

| فرع حيوي: | Maniraptora |

| Clade: | Pennaraptora |

| Clade: | أشباه الطيور سرنو، 1997 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

أشباه الطيور Paraves هي a branch-based clade defined to include all dinosaurs التي هي علاى قرابة وثيقة بالطيور أكثر من قرابتها بـoviraptorosaurs. وتتكون أشباه الطيور من مجموعتين فرعيتين كبيرتين: Avialae، بما فيها Jeholornis والطيور الحديثة، و Deinonychosauria، التي تضم dromaeosaurids و troodontids، التي قد تشكل أو لا تشكل مجموعة طبيعية.

كلٌ من العملقة والتقزم حدثا في Coelurosauria, but the most extreme examples of miniaturization and progenesis, accelerated sexual maturation which emerge during a phase that would be considered juvenile in the predecessors, at which both growth and further anatomical development slows down or cease, is found in Paraves.[1] The ancestors of Paraves first started to shrink in size in the early Jurassic 200 million years ago, and fossil evidence show that this theropod line evolved new adaptations four times faster than other groups of dinosaurs.[2] Turner et al. (2007) suggested that extreme miniaturization was ancestral for the clade, whose common ancestor has been estimated to have been around 65 centimeters long and 600-700 grams in mass. In Eumaniraptora, Dromaeosauridae and Troodontidae went later through four independent events of gigantism, three times in dromaeosaurids and once in troodontids, while the body mass continued to decrease in many forms within Avialae.[3] Fossils shows that all the earliest members of Paraves found to date started out as small, but within Troodontidae and Dromaeosauridae, they gradually increased in size during the Cretaceous period.[3]

The ancestral paravian is a hypothetical animal; the first common ancestor of birds, dromaeosaurids, and troodontids which was not also ancestral to oviraptorosaurs. Little can be said with certainty about this animal. But the work of Xu et al. (2003), (2005) and Hu et al. (2009) provide examples of basal and early paravians with four wings,[4][5][6] adapted to an arboreal lifestyle who would only lose their hindwings when some adapted to a life on the ground and when avialans evolved powered flight.[7] Newer research also indicates that gliding, flapping and parachuting was another ancestral trait of Paraves, while true powered flight only evolved once, in the lineage leading to modern birds.[8]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الوصف

Like other theropods, early paravians are bipedal; that is, they walk on their two hind legs. However, whereas most theropods walked with three toes contacting the ground, fossilized footprint tracks confirm that many basal paravians, including dromaeosaurids, troodontids, and some early avialans, held the second toe off the ground in a hyperextended position, with only the third and fourth toes bearing the weight of the animal. This is called functional didactyly.[9] The enlarged second toe bore an unusually large, curved sickle-shaped claw (held off the ground or 'retracted' when walking). This claw was especially large and flattened from side to side in the large-bodied predatory eudromaeosaurs.[10] In these early species, the first toe (hallux) was usually small and angled inward toward the center of the body, but only became fully reversed in more specialized members of the bird lineage.[11] One species, Balaur bondoc, possessed a first toe which was highly modified in parallel with the second. Both the first and second toes on each foot of B. bondoc were held retracted and bore enlarged, sickle-shaped claws.[12]

وظيفة المخلب

التبويب

الاسم أشباه الطيور Paraves صاغه پول سرنو في 1997.[13] The clade was defined by Sereno in 1998 as a branch-based clade containing all Maniraptora closer to Neornithes (which includes all the birds living in the world today) than to Oviraptor.[14]

The cladogram below follows the results of a phylogenetic study by Lefèvre et al., 2014:[15]

| أشباه الطيور |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

الهامش

- ^ Bhullar, B.A.; et al. (2012). "have paedomorphic dinosaur skulls". Nature. 487 (7406): 223–226. doi:10.1038/nature11146. PMID 22722850.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first1=(help) - ^ Dinosaurs 'shrank' regularly to become birds

- ^ أ ب Turner, Alan H.; Pol, Diego; Clarke, Julia A.; Erickson, Gregory M.; Norell, M. (2007). "A basal dromaeosaurid and size evolution preceding avian flight". Science. 317 (5843): 1378–1381. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1378T. doi:10.1126/science.1144066. PMID 17823350.

- ^ Hu, Dongyu; Lianhi, Hou; Zhang, Lijun; Xu, Xing (2009). "A pre-Archaeopteryx troodontid theropod from China with long feathers on the metatarsus". Nature. 461 (7264): 640–643. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..640H. doi:10.1038/nature08322. PMID 19794491.

- ^ Xing, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Kuang, X.; Zhang, F.; Du, X. (2003). "Four-winged dinosaurs from China". Nature. 421 (6921): 335–340. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..335X. doi:10.1038/nature01342. PMID 12540892.

- ^ Xu, X.; Zhang, F. (2005). "A new maniraptoran dinosaur from China with long feathers on the metatarsus". Naturwissenschaften. 92 (4): 173–177. Bibcode:2005NW.....92..173X. doi:10.1007/s00114-004-0604-y. PMID 15685441.

- ^ Palaeontology: Dinosaurs take to the air

- ^ New insights into the origin of birds

- ^ Li, Rihui (2007). "Behavioral and faunal implications of Early Cretaceous deinonychosaur trackways from China". Naturwissenschaften. 95 (3): 185–91. Bibcode:2008NW.....95..185L. doi:10.1007/s00114-007-0310-7. PMID 17952398.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Longrich, N.R.; Currie, P.J. (2009). "A microraptorine (Dinosauria–Dromaeosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of North America". PNAS. 106 (13): 5002–7. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.5002L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811664106. PMC 2664043. PMID 19289829.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةfowleretal2011 - ^ Z., Csiki; Vremir, M.; Brusatte, S. L.; Norell, M. A. (in press). "An aberrant island-dwelling theropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Romania". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (35): 15357–61. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10715357C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1006970107. PMC 2932599. PMID 20805514.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) Supporting Information - ^ Sereno, P. C., 1997, "The origin and evolution of dinosaurs", Annual Review of Earth & Planetary Sciences 25:435- 489. (21)

- ^ Sereno, P. C., 1998, "A rationale for phylogenetic definitions, with application to the higher level taxonomy of Dinosauria", Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Abhandlungen 210:41-83. (23)

- ^ DOI:10.1111/bij.12343

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand