توازن القشرة الأرضية

التوازن الأرضي Isostasy ، هي نظرية تؤمن في أن ارتفاع الكتل القارية بالنسبة للأحواض المحيطية إنما يرجع إلى أن الصخور التي تتكون منها كتل القارات صخور قليلة الكثافة خفيفة الوزن وهي صخور السيال الجرانيتية والتي لابد وأن تطفو فوق صخور السيما الثقيلة الوزن والمرتفعة الكثافة، والتي تتكون منها قيعان الأحواض المحيطية، ولذلك تبدو تلك الكتل كالسفن الطافية فوق سطح الماء. ويمكن القول كذلك بأن السلاسل الجبلية ترتفع هي الأخرى فوق سطح القارات لأنها تتكون من صخور قليلة الكثافة لها جذور تمتد إلى أعماق بعيدة عن سطح الأرض. [1]

ولكي تحتفظ كتل السيال الجرانيتية – التي تكون القارات – بتوازنها فوق طبقة السيما البازلتية التي تكون قيعان الأحواض الميحيطة، ولكي تحتفظ السلاسل الجبلية المرتفعة أيضا بتوازنها فوق كتل القارات، لابد أن يغطس ويتعمق جزء كبير منها في طبقة السيما يبلغ في المتوسط حوالي ثمانية أمثال الجزء الظاهر من هذه الكتل فوق سطح الأرض. وهي في هذا تشبه الجبال الثلجية التي إنما يساعد على حفظ توازنها فوق سطح الماء أن أجزاءها الغائصة تبلغ في المعتاد تسعة أمثال الأجزاء الظاهرة منها فقو سطح البحر، فالأجزاء الغاطسة من كتل السيال في طبقة السيما عبارة عن أعمدة تحفظ توازن الأجزاء الظاهرة فقو طبقة السميا أو الطافية فوقها بمعنى آخر. فكأن كتل القارات إنا يساعد على حفظ توزانها أنها تتألف من مواد جرانيتية خفيفة تتمعق في مادة السيما البازلتية الثقيلة، وبذا تشغل في هذه المادة الأخيرة فراغا لولاه لشغتله المواد البازلتية، ولأصبحت الجبال والقارات موادا زائدة عن حاجة الارض، ولكانت عرضة لأن تتطاير مع دوران الكرة الأرضية.

ويؤدي الأخذ بنظرية التوازن إلى الاعتقاد بأن طبقة السيما التي تمثل الطبقة السفلية من الغلاف الصخري، لابد أن تكون في حالة سائلة كي تتمكن كتل السيال من أن تتعمق فيها بسهولة. أما اذا كانت طبقة السيما في حالة تامة من الصلابة فلا يمكن بأي حال لجذور كتل السيال من أن تتعمق فيها. ولكننا اذا تذكرنا ما قيل من قبل من أن طبقة السيما في حالة مرنة، فإن هذا يفسر لنا توازن كتل السيال فوق طبقة السيما المرنة المطاطة التي تتكون منها في أغلب الحالات قيعان الأحواض المحيطية.

تاريخ المفهوم

In the 17th and 18th centuries, French geodesists (for example, Jean Picard) attempted to determine the shape of the Earth (the geoid) by measuring the length of a degree of latitude at different latitudes (arc measurement). A party working in Ecuador was aware that its plumb lines, used to determine the vertical direction, would be deflected by the gravitational attraction of the nearby Andes Mountains. However, the deflection was less than expected, which was attributed to the mountains having low-density roots that compensated for the mass of the mountains. In other words, the low-density mountain roots provided the buoyancy to support the weight of the mountains above the surrounding terrain. Similar observations in the 19th century by British surveyors in India showed that this was a widespread phenomenon in mountainous areas. It was later found that the difference between the measured local gravitational field and what was expected for the altitude and local terrain (the Bouguer anomaly) is positive over ocean basins and negative over high continental areas. This shows that the low elevation of ocean basins and high elevation of continents is also compensated at depth.[2]

The American geologist Clarence Dutton use the word 'isostasy' in 1889 to describe this general phenomenon.[3][4][5] However, two hypotheses to explain the phenomenon had by then already been proposed, in 1855, one by George Airy and the other by John Henry Pratt.[6] The Airy hypothesis was later refined by the Finnish geodesist Veikko Aleksanteri Heiskanen and the Pratt hypothesis by the American geodesist John Fillmore Hayford.[7]

Both the Airy-Heiskanen and Pratt-Hayford hypotheses assume that isostacy reflects a local hydrostatic balance. A third hypothesis, lithospheric flexure, takes into account the rigidity of the Earth's outer shell, the lithosphere.[8] Lithospheric flexure was first invoked in the late 19th century to explain the shorelines uplifted in Scandinavia following the melting of continental glaciers at the end of the last glaciation. It was likewise used by American geologist G. K. Gilbert to explain the uplifted shorelines of Lake Bonneville.[9] The concept was further developed in the 1950s by the Dutch geodesist Vening Meinesz.[7]

نماذج التوازن الأرضي

يوجد ثلاث نماذج رئيسية من التوازن الأرضي:

Airy

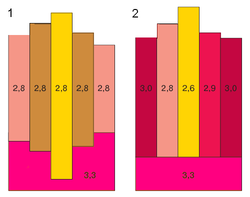

- نموذج أيري-هايسكانن

The basis of the model is Pascal's law, and particularly its consequence that, within a fluid in static equilibrium, the hydrostatic pressure is the same on every point at the same elevation (surface of hydrostatic compensation):[7][6]

h1⋅ρ1 = h2⋅ρ2 = h3⋅ρ3 = ... hn⋅ρn

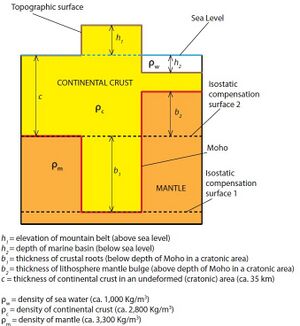

For the simplified picture shown, the depth of the mountain belt roots (b1) is calculated as follows:

where is the density of the mantle (ca. 3,300 kg m−3) and is the density of the crust (ca. 2,750 kg m−3). Thus, generally:

- b1 ≅ 5⋅h1

In the case of negative topography (a marine basin), the balancing of lithospheric columns gives:

where is the density of the mantle (ca. 3,300 kg m−3), is the density of the crust (ca. 2,750 kg m−3) and is the density of the water (ca. 1,000 kg m−3). Thus, generally:

- b2 ≅ 3.2⋅h2

پرات

For the simplified model shown the new density is given by: , where is the height of the mountain and c the thickness of the crust.[7][10]

Vening Meinesz / flexural

This hypothesis was suggested to explain how large topographic loads such as seamounts (e.g. Hawaiian Islands) could be compensated by regional rather than local displacement of the lithosphere. This is the more general solution for lithospheric flexure, as it approaches the locally compensated models above as the load becomes much larger than a flexural wavelength or the flexural rigidity of the lithosphere approaches zero.[7][8]

For example, the vertical displacement z of a region of ocean crust would be described by the differential equation

where and are the densities of the aesthenosphere and ocean water, g is the acceleration due to gravity, and is the load on the ocean crust. The parameter D is the flexural rigidity, defined as

where E is Young's modulus, is Poisson's ratio, and is the thickness of the lithosphere. Solutions to this equation have a characteristic wave number

As the rigid layer becomes weaker, approaches infinity, and the behavior approaches the pure hydrostatic balance of the Airy-Heiskanen hypothesis.[11]

اختلاف التوازن الأرضي

ومن المؤكد الآن أن حالة التوازن الأرضي حالة نظرية نادرا ما تتم، وذلك بسبب العمليات الجيولوجية التي تؤثر في منطقة ما ويتسبب عنها إزالة بعض التكوينات من قمم الجبال وإرسابها في المناطق المنخفضة، كما أن تراكم الرواسب بشتى أنواعها وتكون الغطاءات الجليدية إلى غير ذلك مما ينجم عن العمليات الجيولوجية المختلفة التي تشكل سطح الأرض، لابد أن يؤدي إلى الاخلال بحالة التوازن الأرضي التي ذكرناها. فاذا ما عملت عوامل النحت مثلا على تقطيع سلسلة جبلية متصلة إلى مجموعة من القمم الجبلية تفصل بينها أودية عميقة، أو اذا أزالت هذه العوامل بعض التكوينات من تلك القمم، فان معنى هذا أن كتلة عمود السيال الذي يتعمق في مادة السيما تحت السلسلة الجبلية المذكورة لابد أن تتناقص، ولابد أن يزيد في نفس الوقت الضغط الواقع على عمود مجاور يقع تحت منطقة دلتاوية نتيجة تراكم الوراسب الدلتاوية فوقه، ولهذا لابد أن تحدث حركة ما في طبقة السيما بحيث تعمل على استعادة توازن هذين العمودين إلى ما كانا عليه قبل تعرضهما لعوامل النحت والإرساب، فيهبط العمود الذي زادت كتلته ، ويرتفع العمود الذي اقتطعت منه بعض التكوينات، ونظرا لمرونة الطبقات السفلى من الغلاف الصخري وعدم سيولتها فإن مثل هذا الارتفاع والهبوط في الكتل اليابسة لابد أني يستغرف وقتا طويلا لكي يتم، وتسمى مثل هذه الحركات البطئية التي تتعرض لها قشرة الأرض بالحركات التوازنية isostatic movements.

تأثير التوزان الأراضي على الترسيب والتأكل

تأثير التوزان الأرضي على الصفائح التكتونية

مقالة مفصلة: الصفائح التكتونية

مقالة مفصلة: الصفائح التكتونية

تأثير التوازن الأرضي على الكتل الثلجية

Eustasy and relative sea level change

قراءات إضافية

- Lisitzin, E. (1974) "Sea level changes". Elsevier Oceanography Series, 8

- AB Watts (2001). Isostasy and Flexure of the Lithosphere. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521006007. A very complete overview with much of the historical development.

انظر أيضا

- كلارنس دوتون، الذي أنشأ مصطلح التوزان الأرضي عام 1889.

- جون فلمور هايفورد

- وليام بوي (مهندس)

- Lau, Gotland

- Marine terrace

- Gravity anomaly

- Timeline of the development of tectonophysics (before 1954)

المصادر

- ^

أبو العز, محمد صفي الدين (2001). قشرة الأرض. القاهرة، مصر: دار غريب للطباعة والنشر والتوزيع.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Kearey, P.; Klepeis, K.A.; Vine, F.J. (2009). Global tectonics (3rd ed.). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 42. ISBN 9781405107778.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةDutton1882 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةOrme2007 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةcdutton1958 - ^ أ ب Kearey, Klepeis & Vine 2009, p. 43.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةWatts2001 - ^ أ ب Kearey, Klepeis & Vine 2009, pp. 44-45.

- ^ Gilber, G.K. (1890). "Lake Bonneville". U.S. Geological Survey Monograph. 1. doi:10.3133/m1.

- ^ Kearey, Klepeis & Vine 2009, pp. 43-44.

- ^ Kearey, Klepeis & Vine 2009, p. 45.

![{\displaystyle c\rho _{c}=(h_{2}\rho _{w})+(b_{2}\rho _{m})+[(c-h_{2}-b_{2})\rho _{c}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2fed9708a37e32b3c6e88d7353e28bb979f8de9f)

![{\displaystyle \kappa ={\sqrt[{4}]{(\rho _{m}-\rho _{w})g/4D}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/26610c59d48b3e4b5e0bcf2320f97228557e62b6)