صياد وجامع ثمار

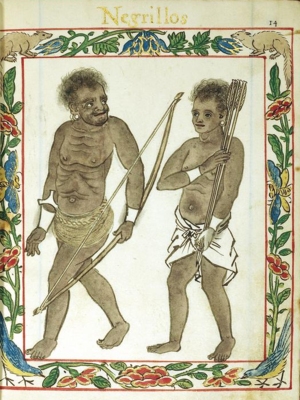

A hunter-gatherer is a human living in a society in which most or all food is obtained by foraging (collecting wild plants and pursuing wild animals). Hunter-gatherer societies stand in contrast to agricultural societies, which rely mainly on domesticated species.

Hunting and gathering was humanity's first and most successful adaptation, occupying at least 90 percent of human history.[1] Following the invention of agriculture, hunter-gatherers who did not change have been displaced or conquered by farming or pastoralist groups in most parts of the world.[2]

Only a few contemporary societies are classified as hunter-gatherers, and many supplement their foraging activity with horticulture or pastoralism.[3][4] Contrary to common misconception, hunter-gatherers are mostly well-fed, rather than starving.[5]

Archaeological evidence

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| الأنظمة الاقتصادية |

|---|

|

|

Common characteristics

Habitat and population

Most hunter-gatherers are nomadic or semi-nomadic and live in temporary settlements. Mobile communities typically construct shelters using impermanent building materials, or they may use natural rock shelters, where they are available.

Variability

Modern and revisionist perspectives

Americas

Evidence suggests big-game hunter-gatherers crossed the Bering Strait from Asia (Eurasia) into North America over a land bridge (Beringia), that existed between 47,000–14,000 years ago.[7] Around 18,500–15,500 years ago, these hunter-gatherers are believed to have followed herds of now-extinct Pleistocene megafauna along ice-free corridors that stretched between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.[8] Another route proposed is that, either on foot or using primitive boats, they migrated down the Pacific coast to South America.[9][10]

See also

Modern hunter-gatherer groups

- Aeta people

- Aka people

- Andamanese people

- Angu people

- Awá-Guajá people

- Batek people

- Efé people

- Fuegians

- Hadza people

- Indigenous Australians

- Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast

- Inuit people

- Iñupiat

- Jarawa people (Andaman Islands)

- Kawahiva people

- Maniq people

- Mbuti people

- Mlabri people

- Moriori people

- Nukak people

- Onge people

- Penan people

- Pirahã people

- San people

- Semang people

- Sentinelese people

- Spinifex People

- Tjimba people

- Yakuts

- Yaruro (Pumé) people

- Ye'kuana people

- Yupik people

Social movements

- Anarcho-primitivism, which strives for the abolishment of civilization and the return to a life in the wild.

- Freeganism involves gathering of food (and sometimes other materials) in the context of an urban or suburban environment.

- Gleaning involves the gathering of food that traditional farmers have left behind in their fields.

- Paleolithic diet, which strives to achieve a diet similar to that of ancient hunter-gatherer groups.

- Paleolithic lifestyle, which extends the paleolithic diet to other elements of the hunter-gatherer way of life, such as movement and contact with nature

References

- ^ Lee, Richard B.; Daly, Richard Heywood (1999). Cambridge Encyclopedia of Hunters and Gatherers. Cambridge University Press. p. inside front cover. ISBN 978-0521609197.

- ^ Stephens, Lucas; Fuller, Dorian; Boivin, Nicole; Rick, Torben; Gauthier, Nicolas; Kay, Andrea; Marwick, Ben; Armstrong, Chelsey Geralda; Barton, C. Michael (2019-08-30). "Archaeological assessment reveals Earth's early transformation through land use". Science (in الإنجليزية). 365 (6456): 897–902. doi:10.1126/science.aax1192. hdl:10150/634688. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 31467217.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:0 - ^ Greaves, Russell D.; et al. (2016). "Economic activities of twenty-first century foraging populations". Why Forage? Hunters and Gatherers in the Twenty-First Century. Santa Fe, Albuquerque: School for Advanced Research, University of New Mexico Press. pp. 241–262. ISBN 978-0826356963.

- ^ Visualizing Human Geography, Second edition, Alyson L. Greinerقالب:ISBN?

- ^ Peterson, Nicolas; Taylor, John (1998). "Demographic transition in a hunter-gatherer population: the Tiwi case, 1929–1996". Australian Aboriginal Studies. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. 1998.

- ^ "Atlas of the Human Journey-The Genographic Project". National Geographic Society. 1996–2008. Archived from the original on 2011-05-01. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ^ "The peopling of the Americas: Genetic ancestry influences health". Scientific American. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ Fladmark, K. R. (January 1979). "Alternate Migration Corridors for Early Man in North America". American Antiquity. 1. 44 (1): 55–69. doi:10.2307/279189. JSTOR 279189.

- ^ Eshleman, Jason A.; Malhi, Ripan S.; Smith, David Glenn (2003). "Mitochondrial DNA Studies of Native Americans: Conceptions and Misconceptions of the Population Prehistory of the Americas". Evolutionary Anthropology. University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. 12: 7–18. doi:10.1002/evan.10048. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

Further reading

- Books

- Barnard, A. J., ed. (2004). Hunter-gatherers in history, archaeology and anthropology. Berg. ISBN 1-85973-825-7.

- Bettinger, R. L. (1991). Hunter-gatherers: archaeological and evolutionary theory. Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-43650-7.

- Bowles, Samuel; Gintis, Herbert (2011). A Cooperative Species: Human Reciprocity and Its Evolution. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15125-0. (Reviewed in The Montreal Review)

- Brody, Hugh (2001). The Other Side Of Eden: hunter-gatherers, farmers and the shaping of the world. North Point Press. ISBN 0-571-20502-X.

- Codding, Brian F.; Kramer, Karen L., eds. (2016). Why forage?: hunters and gatherers in the twenty-first century. Santa Fe, Albuquerque: School for Advanced Research Press, University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0826356963.

- Lee, Richard B.; DeVore, Irven, eds. (1968). Man the hunter. Aldine de Gruyter. ISBN 0-202-33032-X.

- Meltzer, David J. (2009). First peoples in a new world: colonizing ice age America. Berkeley: University of California. ISBN 978-0-520-25052-9.

- Morrison, K. D.; L. L. Junker, eds. (2002). Forager-traders in South and Southeast Asia: long term histories. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01636-3.

- Panter-Brick, C.; R. H. Layton; P. Rowley-Conwy, eds. (2001). Hunter-gatherers: an interdisciplinary perspective. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77672-4.

- Turnbull, Colin (1987). The Forest People. Touchstone. ISBN 978-0-671-64099-6.

- Articles

- Mudar, Karen; Anderson, Douglas D. (Fall 2007). "New evidence for Southeast Asian Pleistocene foraging economies: faunal remains from the early levels of Lang Rongrien rockshelter, Krabi, Thailand" (PDF). Asian Perspectives. 46 (2): 298–334. doi:10.1353/asi.2007.0013. hdl:10125/17269.(يتطلب اشتراك)

- Nakao, Hisashi; Tamura, Kohei; Arimatsu, Yui; Nakagawa, Tomomi; Matsumoto, Naoko; Matsugi, Takehiko (30 March 2016). "Violence in the prehistoric period of Japan: the spatio-temporal pattern of skeletal evidence for violence in the Jomon period". Biology Letters. The Royal Society publishing. 12 (3): 20160028. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2016.0028. PMC 4843228. PMID 27029838.

Our results suggest that the mortality due to violence was low and spatio-temporally highly restricted in the Jomon period, which implies that violence including warfare in prehistoric Japan was not common.

- Ember, Carol R. "Hunter Gatherers (Foragers)". Explaining Human Culture. Human Relations Area Files. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

Most cross-cultural research aims to understand shared traits among hunter-gatherers and how and why they vary. Here we look at the conclusions of cross-cultural studies that ask: What are recent hunter-gatherers generally like? How do they differ from food producers? How and why do hunter-gatherers vary?

External links

- International Society for Hunter Gatherer Research (ISHGR)

- History of the Conference on Hunting and Gathering Societies (CHAGS)

Media related to Hunter-gatherers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hunter-gatherers at Wikimedia Commons- The Association of Foragers: An international association for teachers of hunter-gatherer skills.

- A wiki dedicated to the scientific study of the diversity of foraging societies without recreating myths

- Balmer, Yves (2013). "Ethnological videos clips. Living or recently extinct traditional tribal groups and their origins". Andaman Association. Archived from the original on January 11, 2014.

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Articles with long short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- صفحات تحتوي روابط لمحتوى للمشتركين فقط

- تصنيفات أنثروپولوجية للشعوب

- Nomads

- Stone Age

- Hunter-gatherers

- تطور بشري

- Economic systems

- Foraging