ساحل العبيد الهولندي

ساحل العبيد الهولندي Slavenkust | |

|---|---|

| 1660–1760 | |

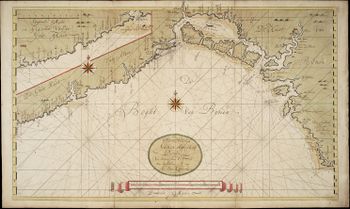

The Slave Coast around 1716. | |

| الوضع | مستعمرة |

| العاصمة | أوفرا (1660–1691) ويدا (1691–1724) ياكيم (1726–1734) |

| اللغات المشتركة | الهولندية |

| الدين | الكنيسة الإصلاحية الهولندية |

| الحاكم | |

| التاريخ | |

• تأسست | 1660 |

• انحلت | 1760 |

ساحل العبيد الهولندي (بالهولندية: Slavenkust) يشير إلى النقاط التجارية التابعة لشركة الهند الغربية الهولندية على ساحل العبيد، الواقع في ما هو اليوم غانا وبنين وتوگو ونيجيريا. الغرض الرئيسي من النقطة التجارية كان توريد عبيد لمستعمرات المزارع في الأمريكتين. الانخراط الهولندي في ساحل العبيد بدأ بتأسيس نقطة تجارة في أوفرا في 1660. ولاحقاً، انتقلت التجارة إلى ويدا، حيث كان للإنگليز والفرنسيين أيضاً نقاط تجارة. تسببت القلاقل السياسية في أن يهجر الهولنديون نقطتهم التجارية في ويدا في 1725، وانتقلوا إلى ياكيم، والتي فيها شيدوا حصن زيلانديا. بحلول 1760، هجر الهولنديون آخر نقاطهم التجارية في المنطقة.

ساحل العبيد تم استيطانه من ساحل الذهب الهولندي، حيث كان يتمركز الهولنديون في المينا. وخلال وجوده، أقام ساحل العبيد علاقة وثيقة مع تلك المستعمرة.

التاريخ

According to various sources, the Dutch West India Company began sending servants regularly to the Ajaland capital of Allada from 1640 onward. The Dutch had in the decades before begun to take an interest in the Atlantic slave trade due to their capture of northern Brazil from the Portuguese. Willem Bosman writes in his Nauwkeurige beschrijving van de Guinese Goud- Tand- en Slavekust (1703) that Allada was also called Grand Ardra, being the larger cousin of Little Ardra, also known as Offra. From 1660 onward, Dutch presence in Allada and especially Offra became more permanent.[1] A report from this year asserts Dutch trading posts, apart from Allada and Offra, in Benin City, Grand-Popo, and Savi.

The Offra trading post soon became the most important Dutch office on the Slave Coast. According to a 1670 report, annually 2,500 to 3,000 slaves were transported from Offra to the Americas and writing of the 1690s, Bosman commented of the trade at Fida, "markets of men are here kept in the same manner as those of beasts are with us."[2] Numbers of slaves declined in times of conflict. From 1688 onward, the struggle between the Aja king of Allada and the peoples on the coastal regions, impeded the supply of slaves. The Dutch West India Company chose the side of the Aja king, causing the Offra office to be destroyed by opposing forces in 1692. After this debacle, Dutch involvement on the Slave Coast came more or less to a halt.[3]

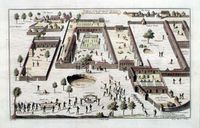

During his second voyage to Benin, David van Nyendael visited the king of Benin in Benin City. His detailed description of this journey was included as an appendix to Willem Bosman's Nauwkeurige beschrijving van de Guinese Goud- Tand- en Slavekust (1703). His description of the kingdom remains valuable as one of the earliest detailed descriptions of Benin.[4]

On the instigation of Governor-General of the Dutch Gold Coast Willem de la Palma, Jacob van den Broucke was sent in 1703 as "opperkommies" (head merchant) to the Dutch trading post at Ouidah, which according to sources was established around 1670. Ouidah was also a slave-trading center for other European slave traders, making this place the likely candidate for the new main trading post on the Slave Coast..[5][6]

Political unrest was also the reason for the Ouidah office to close in 1725. The company this time moved their headquarters to Jaquim, situated more easterly.[5] The head of the post, Hendrik Hertog, had a reputation for being a successful slave trader. In an attempt to extend his trading area, Hertog negotiated with local tribes and mingled in local political struggles. He sided with the wrong party, however, leading to a conflict with Director-General Jan Pranger and to his exile to the island of Appa in 1732. The Dutch trading post on this island was extended as the new centre of slave trade. In 1733, Hertog returned to Jaquim, this time extending the trading post into Fort Zeelandia. The revival of slave trade at Jaquim was only temporary, however, as his superiors at the Dutch West India Company noticed that Hertog's slaves were more expensive than at the Gold Coast. From 1735, Elmina became the preferred spot to trade slaves.[7]

الوقع على البشر

The transatlantic slave trade resulted in a vast and as yet unknown loss of life for African captives both in and outside the Americas. "More than a million people are thought to have died" during their transport to the New World according to a BBC report.[8] More died soon after their arrival. The number of lives lost in the procurement of slaves remains a mystery but may equal or exceed the number who survived to be enslaved.[9]

The savage nature of the trade led to the destruction of individuals and cultures. Historian Ana Lucia Araujo has noted that the process of enslavement did not end with arrival on Western Hemisphere shores; the different paths taken by the individuals and groups who were victims of the Atlantic slave trade were influenced by different factors—including the disembarking region, the ability to be sold on the market, the kind of work performed, gender, age, religion, and language.[10][11]

Patrick Manning estimates that about 12 million slaves entered the Atlantic trade between the 16th and 19th century, but about 1.5 million died on board ship. About 10.5 million slaves arrived in the Americas. Besides the slaves who died on the Middle Passage, more Africans likely died during the slave raids in Africa and forced marches to ports. Manning estimates that 4 million died inside Africa after capture, and many more died young. Manning's estimate covers the 12 million who were originally destined for the Atlantic, as well as the 6 million destined for Asian slave markets and the 8 million destined for African markets.[12] Of the slaves shipped to The Americas, the largest share went to Brazil and the Caribbean.[13]

مواقع التبادل التجاري

| الموقع في غرب أفريقيا | تأسس | انحل | تعليقات |

|---|---|---|---|

| أوفرا (Pla, Cleen Ardra, Klein Ardra, Offra) | 1660 | 1691 | As the original head trading post at the Dutch Slave Coast, Offra was established in 1660. According to a 1670 report, 2,500 to 3,000 slaves were transported annually from Offra. Due to the Dutch siding with the Aja in the local political struggles, the fort was destroyed in 1692.[3] |

| ألادا (Ardra, Ardres, Arder, Allada, Harder) | 1660 | ? | According to sources, the Dutch West India Company began sending servants to Allada, the capital of Ajaland, already in 1640. In some sources, Allada is referred to as "Grand Ardra", to contrast it with "Little Ardra", which is another name for Offra.[1] |

| مدينة بنين | 1660 | 1740 | In contemporary Nigeria. |

| پوپو الكبرى | 1660 | ? | |

| ساڤي (Sabee, Xavier, Savy, Savé, Sabi, Xabier) | 1660 | ? | In the beginning of the 18th century, the Dutch had a small trading post in Savi (capital of the Kingdom of Whydah), next to the Royal Palace. Compared to the English and French trading posts, the Dutch post was rather minimalistic in nature.[14] |

| ويدا (Fida, Whydah, Juda, Hueda, Whidah) | 1670 | 1725 | Ouidah was the centre of slave trade for the French and English on the Slave Coast. In 1703, Governor-General of the Gold Coast Willem de la Palma sent Jacob van den Broucke as "head merchant" to Ouidah in 1703. Abandoned in 1725, in favour of the post at Jaquim, due to political unrest at the Slave Coast.[5] |

| أگاثون (Aggathon, Agotton) | 1717 | ? | The trading post at Agathon, in contemporary Nigeria, was situated on a hill on the banks of the Benin River (also: Rio Formoso). Agathon was an important post for the trade in clothes, especially the so-called "Benijnse panen". In 1718-1719, the post produced 31,092 pounds of ivory.[15] |

| ياكيم (Jaquin, Jakri, Godomey, Jakin) | 1726 | 1734 | One of the most successful post at the slave coast. Became the head post after Ouidah was abandoned in 1725. In 1733 Fort Zeelandia was built here, but two years later, the directors of the Dutch West India Company decided to shift the slave trade to Elmina Castle, where slaves were cheaper.[7] |

| أنيهو (Petit Popo, Little Popo, Klein Popo, Popou) | 1731 | 1760 | Little Popo, also known as Aného, was the most westerly post on the Slave Coast. Due to this, the post suffered from competition of the Danish Africa Company, based at the Danish Gold Coast.[16] |

| أپـّا 1 | 1732 | 1736? | The island of Appa lies to the east of Offra. To this island, Hendrik Hertog, the merchant at Jaquim, fled in 1732 when he sided with the defeated party in a local conflict. On this island, a new trading post was founded, which was supposed to replace Jaquim. Appa and rebuilt Jaquim, now known as Fort Zeelandia, became a prominent centre of slave trade for some time, until 1735, when the Dutch West India Company decided to shift slave supply to Elmina on the Gold Coast. Hertog fled to Pattackerie in 1738, fearing that Appa would be attacked by local tribes as well.[17] |

| أپـّا 2 (Epe, Ekpe) | 1732 | 1755? | Appa 2 is the name used in some literature to refer to the trading post Hendrik Hertog fled to from the island of Appa, east of Offra. He named the new post Appa as well, but this post was situated near Pattackerie (contemporary Badagri).[18] |

| بدگري (Pattackerie) | 1737 | 1748 | Referred to on the Atlas of Mutual Heritage as a separate trading post distinct from "Appa 2", also located at Badagri. It is unsure whether there were two separate trading posts in reality, or that the posts are one and the same.[19] |

| مايدورپ (مايبورگ) | ? | ? | Meidorp was situated at the River Benin (also: Rio Formoso). It was a simple lodge, named by Dutch traders. It was abandoned after the last merchant named Beelsnijder turned the local population against him, due to his tactless approach towards them.[20] |

الهامش

- ^ أ ب Atlas of Mutual Heritage. "Plaats: Allada (Ardra, Ardres, Arder, Allada, Harder)". Archived from the original on 3 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Woolman, John (1837). A Journal of the Life, Gospel Labours, and Christian Experiences of that Faithful Minister of Jesus Christ, John Woolman. Philadelphia: T E Chapman. p. 233.

- ^ أ ب Atlas of Mutual Heritage. "Plaats: Offra (Pla, Cleen Ardra, Klein Ardra, Offra)". Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Den Heijer 2002, p. 45.

- ^ أ ب ت Atlas of Mutual Heritage. "Plaats: Ouidah (Fida, Whydah, Juda, Hueda, Whidah)". Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Delepeleire 2004, section 3.c.2.

- ^ أ ب Atlas of Mutual Heritage. "Plaats: Jaquim (Jaquin, Jakri, Godomey, Jakin)". Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Quick guide: The slave trade; Who were the slaves? BBC News, 15 March 2007.

- ^ Stannard, David. American Holocaust. Oxford University Press, 1993.

- ^ Paths of the Atlantic Slave Trade: Interactions, Identities, and Images.

- ^ American Freedmen's Inquiry Commission report, page 43-44

- ^ Patrick Manning, "The Slave Trade: The Formal Demographics of a Global System" in Joseph E. Inikori and Stanley L. Engerman (eds), The Atlantic Slave Trade: Effects on Economies, Societies and Peoples in Africa, the Americas, and Europe (Duke University Press, 1992), pp. 117–44, online at pp. 119–120.

- ^ Maddison, Angus. Contours of the world economy 1–2030 AD: Essays in macro-economic history. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- ^ Atlas of Mutual Heritage. "Plaats: Save (Sabee, Xavier, Savy, Savi, Sabi, Xabier)". Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Atlas of Mutual Heritage. "Plaats: Agathon (Aggathon, Agotton)". Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Atlas of Mutual Heritage. "Plaats: Aneho (Petit Popo, Klein Popo, Popou)". Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Atlas of Mutual Heritage. "Plaats: Appa 1". Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Atlas of Mutual Heritage. "Plaats: Appa 2 (Epe, Ekpe)". Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Atlas of Mutual Heritage. "Plaats: Badagri (Pattackerie)". Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ Atlas of Mutual Heritage. "Plaats: Meidorp (Meiborg)". Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

المراجع

- Delepeleire, Y. (2004). Nederlands Elmina: een socio-economische analyse van de Tweede Westindische Compagnie in West-Afrika in 1715. Gent: Universiteit Gent.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Den Heijer, Henk (2002). "David van Nyendael: the first European envoy to the court of Ashanti". In Van Kessel, W. M. J. (ed.). Merchants, missionaries & migrants: 300 years of Dutch-Ghanaian relations. Amsterdam: KIT publishers. pp. 41–49.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

وصلات خارجية

Media related to Dutch Slave Coast at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dutch Slave Coast at Wikimedia Commons

- تاريخ بنين

- مستعمرات سابقة في أفريقيا

- مستعمرات هولندية سابقة

- تجارة العبيد الأفريقية

- الاستعمار الهولندي في أفريقيا

- شركة الهند الغربية الهولندية

- القرن 17 في أفريقيا

- القرن 18 في أفريقيا

- دول وأقاليم تأسست في 1660

- دول وأقاليم انحلت في 1760

- تأسيسات 1660 في أفريقيا

- انحلالات 1760 في أفريقيا

- تأسيسات 1660 في الامبراطورية الهولندية

- انحلالات 1760 في الامبراطورية الهولندية

- مناطق تاريخية