كوني (شعب)

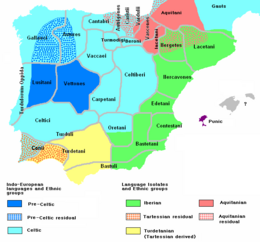

كوني Conii أو كونيو Conios أو كينت Cynetes كانوا أحد pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula, living in today's Algarve and Lower Alentejo regions of southern Portugal, and the southern part of Badajoz and the northwestern portions of Córdoba and Ciudad Real provinces in Spain before the 6th century BCE (in what part of this become the southern part of the Roman province of Lusitania). According to Justin's epitome, the mythical Gargoris and Habis were their founding kings.[2]

أصل الاسم

The name Cynetes (Latin Conii) probably stems from Proto-Celtic *kwon ('dog') connected with greek kyοn, κύων, dog.[3][4]

الأصول والموقع

They are often mentioned in the ancient sources under various designations, mostly Greek or Latin derivatives of their two tribal names: ‘Cynetas’/’Cynetum’;[5] ‘Kunetes’, ‘Kunetas’, and ‘Kunesioi'[6] or ‘Cuneus’,[7] followed by ‘Konioi’,[8] ‘Kouneon’[9] and ‘Kouneous’/‘Kouneoi’.[10] The Conii occupied since the late Bronze Age most of the present-day Lower Alentejo, Algarve, the southern part of Badajoz and the northwestern portions of Córdoba and Ciudad Real provinces,[11] giving the Algarve its pre-Roman name, the Cyneticum. Prior to the Celtic-Turduli migrations of the 5th-4th Centuries BC the original Conii territories also included upper Alentejo and the Portuguese coastal Estremadura region stretching up to the Munda (Mondego) river valley.

الجينات

It has been suggested that the haplotypes HLA-A25-B18-DR15 and HLA-A26-B38-DR13, which are unique genetic markers found in Portugal, may be from the Conii (or Oestrimni).[12]

الثقافة

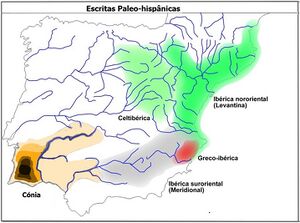

Their presence in these regions is attested archeologically by the elaborated cremation burial-mounds of their ruling elite, whose rich grave-goods and the inscribed slabs in ‘Tartessian alphabet’ – also referred to as ‘Southwest script’ – that mark the graves, evidence contact with North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean since the 9th century BC. Scholars like Schulten, consider the Conii a Ligurian tribe (related to the Ligures of North-western Italy/South-eastern France) and believe that the «Ligurians are the original people of the Iberian Peninsula». The Conii would have left their mark not only in Portugal but also in Spain and European regions where the Ligurians established themselves. They appear to be related to the Aquitanians and the Basques.[13]

Inscriptions in the Tartessian language have been found in the area, in a variety often referred to as Southwest Paleohispanic script.[14][15] The name Conii, found in Strabo, seems to have been identical with the Cynesii, who were mentioned by Herodotus as the westernmost dwellers of Europe and distinguished by him from the Celts.[16]

البلدات

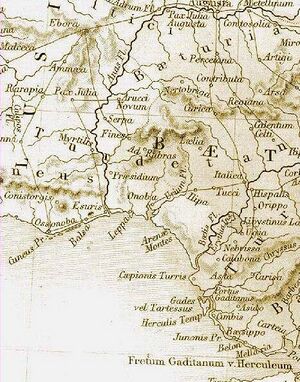

The capital of the Conii was Conistorgis, according to Strabo, who considered the region Celtic.[17] In the local language Conistorgis probably means "City of the Conii". Its precise location has not been determined. Some authors[18] suggest that Pax Julia might have been founded over the ruins of Conistorgis.

Other Conii towns (Oppida) included Ipses (Alvor), Cilpe (Cerro da Rocha Branca – Silves), Ossonoba (near Faro; Iberian-type mint: Osunba), Balsa (Quinta da Torre de Aires, Santa Luzia – Tavira), Baesuris (Castro Marim; Iberian-type mint: Baesuri) and Myrtilis (Mértola; Iberian-type mint: Mrtlis Saidie). According to Pomponius Mela the population of these parva oppida did not surpass 6,000 inhabitants.[19]

A powerful urban aristocracy of Phoenician and Turdetanian or Turduli colonists dominated all the trade, fishing, and shipbuilding in these same coastal settlements since the 4th Century BC, until the Carthaginians occupied the Cyneticum and founded the Punic colonies of Portus Hannibalis (near Portimão?) and Portus Magonis (Portimão) at the late 3rd Century BC.[20]

التاريخ

The Conii seemed to have played no significant role in the Second Punic War and subsequent conflicts, even though they were constantly under the pressure from the northernly Celtic tribes throughout the 3rd-2nd Centuries BC, which may explain their willingness to place themselves under the protection of foreign powers such as Carthage and later Rome.

Around the 3rd Century BC the Celtici reached the western Algarve, establishing a colony at Laccobriga (Monte Molião, near Lagos) and in 153 BC, during the Lusitanian Wars against Rome, Conistorgis fell to the Lusitani and their Vettones' allies.[21] The Conii were thence forced to switch their allegiance from the Roman Republic to the Lusitani, being subjected in 141-140 BC to Consul Quintus Fabius Maximus Servilianus’ reprisal campaigns in the Iberian southwest.[22]

In 138-137 BC the Cyneticum was aggregated into Hispania Ulterior province, only to become again a battleground during the Sertorian Wars, when Quintus Sertorius seized Conistorgis and Consul Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius devastated the region in retaliation,[23] being defeated at the battle of Laccobriga in 78 BC.[24]

الترومُن

In 27-13 BC the romanized Conii were incorporated into Lusitania province.

انظر أيضاً

- تاريخ البرتغال

- أيبيريا قبل التاريخ

- Conistorgis

- Cyneticum

- خط زمني للتاريخ البرتغالي

- Sefes

- Sertorian Wars

- Southwest Paleohispanic script

- "Tartessian" language (Southwestern or "South-Lusitanian" language)

- شعوب شبه جزيرة أيبيريا قبل الرومان

الهامش

- ^ "Arkeotavira.com map". Archived from the original on 2011-02-26. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ^ Justin, Epitome historiarum Trogi Pompeii, 44: 4-5.

- ^ Sergent 1991, p. 12.

- ^ Delamarre 2003, p. 132.

- ^ Avienius, Ora Marítima, 200, 205, 223.

- ^ Herodoros of Heracleia, Fragments.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History, V, 41, 145.

- ^ Polybius, Istorion, 10: 7, 5.

- ^ Strabo, Geographikon, III, 1, 4.

- ^ Appian, Iberiké, 10: 75

- ^ Bendala Galán (1991). Historia General de España y América. De la Protohistoria a la Conquista Romana (2nd ed.). Madrid: Ediciones Rialp, S. A.

- ^ Arnaiz-Villena A, Martínez-Laso J, Gómez-Casado E, Díaz-Campos N, Santos P, Martinho A, Breda-Coimbra H (14 May 2014). "Relatedness among Basques, Portuguese, Spaniards, and Algerians studied by HLA allelic frequencies and haplotypes". Immunogenetics. 47 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1007/s002510050324. PMID 9382919.

- ^ Dr. Manuel Maria da Fonseca Andrade Maia (Dissertação de Doutoramento em Pré-História e Arqueologia [1] Archived فبراير 14, 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Faculdade de Letras de Lisboa, 1987)

- ^ Koch, John T (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 9: Paradigm Shift? Interpreting Tartessian as Celtic. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- ^ Koch, John T (2011). Tartessian 2: The Inscription of Mesas do Castelinho ro and the Verbal Complex. Preliminaries to Historical Phonology. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-907029-07-3. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23.

- ^ Herodotus writes "now the Celtae dwell beyond the pillars of Hercules, being neighbours of the Cynesii, who are the westernmost of all nations inhabiting Europe" (Herodotus, II, 33). In another reference noting the Celts again in the extreme west, he refers to their neighbors the Cynetes: "...the Celts, who, save only the Cynetes, are the most westerly dwellers in Europe." (IV, 49).

- ^ "In the country of the Celti, Conistorgis is the best known city" (Strabo, III, 2, 2).

- ^ Ensaio Monográfico de Beja, 1973, Manuel Joaquim Delgado e Beja XX Séculos de História de Uma Cidade,

- ^ Pomponius Mela, De Chorographia, III, 7.

- ^ Arruda 2005.

- ^ Appian, Iberiké, 56-57.

- ^ Appian, Iberiké, 68-69.

- ^ Sallust, Excerptae de Historiis, 1, 112-113.

- ^ Plutarch, Sertorius, 13.

المراجع

- Arruda, Ana M. (2005). "O 1° milénio a.n.e. no Centro e no Sul de Portugal: leituras possíveis no início de um novo século". O Arqueólogo Português (in البرتغالية). 4: 9–156.

- Berrocal-Rangel, Luis (2005). "The Celts of the Southwestern Iberian Peninsula". e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6: 481–96.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental (in الفرنسية). Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.

- Júdice Gamito, Teresa (2005). "The Celts in Portugal". e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6: 571–605. Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2010-08-12.

- Mattoso, José (dir.), História de Portugal. Primeiro Volume: Antes de Portugal, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 1992. (in Portuguese)

- Sergent, Bernard (1991). "Ethnozoonymes indo-européens". Dialogues d'histoire ancienne. 17 (2). doi:10.3406/dha.1991.1932.

رئيسية

للاستزادة

- Ángel Montenegro et alii, Historia de España 2 - colonizaciones y formación de los pueblos prerromanos (1200-218 a.C), Editorial Gredos, Madrid (1989) ISBN 84-249-1386-8

- Berrocal-Rangel, Luis, Los pueblos célticos del soroeste de la Península Ibérica, Editorial Complutense, Madrid (1992) ISBN 84-7491-447-7

- Philip Matyszak, Sertorius and the struggle for Spain, Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley (2013) ISBN 978-1848847873

- Luis Silva, Viriathus and the Lusitanian resistance to Rome 155-139 BC, Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley (2013) ISBN 9781781591284

- Palacios, Fernando Fernández. "CELTIC ‘DOGS’ IN THE IBERIAN PENINSULA." In Celtic from the West 3: Atlantic Europe in the Metal Ages — Questions of Shared Language, edited by Koch John T. and Cunliffe Barry, by Cleary Kerri and Gibson Catriona D., 477-88. OXFORD: Oxbow Books, 2016. Accessed June 29, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvh1dhg7.19.