كيوپد وپسوخى

كيوپد وپسوخى Cupid and Psyche هي قصة وردت لأول مرة في التحولات (التي تسمى أيضاً الحمار الذهبي)، المكتوبة في القرن الثاني الميلادي بقلم لوكيوس أپوليوس مادورِنسس (أو أفلاطونيكوس).[2] وتتعلق بالتغلب على العقبات التي برزت في وجه الحب بين پسوخى (باليونانية: Ψυχή، "روح" أو "نفـَس الحياة"، وتـُنطق بالإنگليزية "پسايكي" /ˈsaɪkiː/) و كيوپد (باللاتينية Cupido، "رغبة") أو آمور (Amor، أي "حب"، وباليونانية إروس ’′Ερως)، واقترانهما في النهاية في زواج مقدس. وبالرغم من أن الرواية المفصلة الوحيدة من القِدم هي تلك من أپوليوس، إلا أن إروس وپسوخى يظهران في الفن اليوناني منذ القرن الرابع ق.م. فالعناصر الأفلاطونية الحديثة في القصة والتلميحات إلى الديانات الغامضة يناسب العديد من التفسيرات،[3] وقد حـُلـِّلـَت كأمثولة وفي ضوء الحكايات الشعبية، Märchen أو حدوتة خرافية، وأسطورة.[4]

منذ إعادة اكتشاف رواية أپوليوس في عصر النهضة، استقبال كيوپد وپسوخى في التقليد الكلاسيكي كان هائلاً. القصة أعيد سردها شعراً ودراما وأوپرا، وصـُوِّرت على نطاق واسع في الرسم والنحت وحتى ورق الحائط.[5] الاسم الروماني لپسوخى، عبر الترجمة المباشرة هو أنيما Anima.

في أپوليوس

The tale of Cupid and Psyche (or "Eros and Psyche") is placed at the midpoint of Apuleius's novel, and occupies about a fifth of its total length.[6] The novel itself is a first-person narrative by the protagonist Lucius. Transformed into a donkey by magic gone wrong, Lucius undergoes various trials and adventures, and finally regains human form by eating roses sacred to Isis. Psyche's story has some similarities, including the theme of dangerous curiosity, punishments and tests, and redemption through divine favor.[7]

القصة

There was once a king and queen,[8] rulers of an unnamed city, who had three daughters of conspicuous beauty. The youngest and most beautiful was Psyche, whose admirers, neglecting the proper worship of the love goddess Venus, instead prayed and made offerings to her. It was rumored that she was the second coming of Venus, or the daughter of Venus from an unseemly union between the goddess and a mortal. Venus is offended, and commissions Cupid to work her revenge. Cupid instead scratches himself with his own dart, which makes any living thing fall in love with the first thing it sees. As soon as Cupid scratches himself he falls deeply in love with Psyche and disobeys his mother's order to make Psyche fall in love with something hideous.

Although her two humanly beautiful sisters have married, the idolized Psyche has yet to find love. Her father suspects that they have incurred the wrath of the gods, and consults the oracle of Apollo. The response is unsettling: the king is to expect no human son-in-law, but rather a dragon-like creature who harasses the world with fire and iron and is feared by even Jupiter and the inhabitants of the underworld.

Psyche is arrayed in funeral attire, conveyed by a procession to the peak of a rocky crag, and exposed. Marriage and death are merged into a single rite of passage, a "transition to the unknown".[9] Zephyr the West Wind bears her up to meet her fated match, and deposits her in a lovely meadow (locus amoenus), where she promptly falls asleep.

The transported girl awakes to find herself at the edge of a cultivated grove (lucus). Exploring, she finds a marvelous house with golden columns, a carved ceiling of citrus wood and ivory, silver walls embossed with wild and domesticated animals, and jeweled mosaic floors. A disembodied voice tells her to make herself comfortable, and she is entertained at a feast that serves itself and by singing to an invisible lyre.

Although fearful and without sexual experience, she allows herself to be guided to a bedroom, where in the darkness a being she cannot see makes her his wife. She gradually learns to look forward to his visits, though he always departs before sunrise and forbids her to look upon him, and soon she becomes pregnant.

خيانة الثقة

Psyche's family longs for news of her, and after much cajoling, Cupid, still unknown to his bride, permits Zephyr to carry her sisters up for a visit. When they see the splendor in which Psyche lives, they become envious, and undermine her happiness by prodding her to uncover her husband's true identity, since surely as foretold by the oracle she was lying with the vile winged serpent, who would devour her and her child.

One night after Cupid falls asleep, Psyche carries out the plan her sisters devised: she brings out a dagger and a lamp she had hidden in the room, in order to see and kill the monster. But when the light instead reveals the most beautiful creature she has ever seen, she is so startled that she wounds herself on one of the arrows in Cupid's cast-aside quiver. Struck with a feverish passion, she spills hot oil from the lamp and wakes him. He flees, and though she tries to pursue, he flies away and leaves her on the bank of a river.

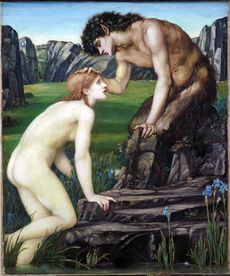

There she is discovered by the wilderness god Pan, who recognizes the signs of passion upon her. She acknowledges his divinity (numen), then begins to wander the earth looking for her lost love.

Psyche visits first one sister, then the other; both are seized with renewed envy upon learning the identity of Psyche's secret husband. Each sister attempts to offer herself as a replacement by climbing the rocky crag and casting herself upon Zephyr for conveyance, but instead is allowed to fall to a brutal death.

Wanderings and trials

In the course of her wanderings, Psyche comes upon a temple of Ceres, and inside finds a disorder of grain offerings, garlands, and agricultural implements. Recognizing that the proper cultivation of the gods should not be neglected, she puts everything in good order, prompting a theophany of Ceres herself. Although Psyche prays for her aid, and Ceres acknowledges that she deserves it, the goddess is prohibited from helping her against a fellow goddess. A similar incident occurs at a temple of Juno. Psyche realizes that she must serve Venus herself.

Venus revels in having the girl under her power, and turns Psyche over to her two handmaids, Worry and Sadness, to be whipped and tortured. Venus tears her clothes and bashes her head into the ground, and mocks her for conceiving a child in a sham marriage. The goddess then throws before her a great mass of mixed wheat, barley, poppyseed, chickpeas, lentils, and beans, demanding that she sort them into separate heaps by dawn. But when Venus withdraws to attend a wedding feast, a kind ant takes pity on Psyche, and assembles a fleet of insects to accomplish the task. Venus is furious when she returns drunk from the feast, and only tosses Psyche a crust of bread. At this point in the story, it is revealed that Cupid is also in the house of Venus, languishing from his injury.

At dawn, Venus sets a second task for Psyche. She is to cross a river and fetch golden wool from violent sheep who graze on the other side. These sheep are elsewhere identified as belonging to the Sun.[11] Psyche's only intention is to drown herself on the way, but instead she is saved by instructions from a divinely inspired reed, of the type used to make musical instruments, and gathers the wool caught on briers.

For Psyche's third task, she is given a crystal vessel in which to collect the black water spewed by the source of the rivers Styx and Cocytus. Climbing the cliff from which it issues, she is daunted by the foreboding air of the place and dragons slithering through the rocks, and falls into despair. Jupiter himself takes pity on her, and sends his eagle to battle the dragons and retrieve the water for her.

Psyche and the underworld

The last trial Venus imposes on Psyche is a quest to the underworld itself. She is to take a box (pyxis) and obtain in it a dose of the beauty of Proserpina, queen of the underworld. Venus claims her own beauty has faded through tending her ailing son, and she needs this remedy in order to attend the theatre of the gods (theatrum deorum).

Once again despairing of her task, Psyche climbs a tower, planning to throw herself off. The tower, however, suddenly breaks into speech, and advises her to travel to Lacedaemon, Greece, and to seek out the place called Taenarus, where she will find the entrance to the underworld. The tower offers instructions for navigating the underworld:

The airway of Dis is there, and through the yawning gates the pathless route is revealed. Once you cross the threshold, you are committed to the unswerving course that takes you to the very Regia of Orcus. But you shouldn’t go emptyhanded through the shadows past this point, but rather carry cakes of honeyed barley in both hands,[12] and transport two coins in your mouth.

The speaking tower warns her to maintain silence as she passes by several ominous figures: a lame man driving a mule loaded with sticks, a dead man swimming in the river that separates the world of the living from the world of the dead, and old women weaving. These, the tower warns, will seek to divert her by pleading for her help: she must ignore them. The cakes are treats for distracting Cerberus, the three-headed watchdog of Orcus, and the two coins for Charon the ferryman, so she can make a return trip.

Everything comes to pass according to plan, and Proserpina grants Psyche's humble entreaty. As soon as she reenters the light of day, however, Psyche is overcome by a bold curiosity, and can't resist opening the box in the hope of enhancing her own beauty. She finds nothing inside but an "infernal and Stygian sleep," which sends her into a deep and unmoving torpor.

Reunion and immortal love

Meanwhile, Cupid's wound has healed into a scar, and he escapes his mother's house by flying out a window. When he finds Psyche, he draws the sleep from her face and replaces it in the box, then pricks her with an arrow that does no harm. He lifts her into the air, and takes her to present the box to Venus.

He then takes his case to Jupiter, who gives his consent in return for Cupid's future help whenever a choice maiden catches his eye. Jupiter has Mercury convene an assembly of the gods in the theater of heaven, where he makes a public statement of approval, warns Venus to back off, and gives Psyche ambrosia, the drink of immortality,[13] so the couple can be united in marriage as equals. Their union, he says, will redeem Cupid from his history of provoking adultery and sordid liaisons.[14] Jupiter's word is solemnized with a wedding banquet.

With its happy marriage and resolution of conflicts, the tale ends in the manner of classic comedy[15] or Greek romances such as Daphnis and Chloe.[16] The child born to the couple will be Voluptas (Greek Hedone ‘Ηδονή), "Pleasure."

The Wedding of Cupid and Psyche

The assembly of the gods has been a popular subject for both visual and performing arts, with the wedding banquet of Cupid and Psyche a particularly rich occasion. With the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, this is the most common setting for a "Feast of the Gods" scene in art. Apuleius describes the scene in terms of a festive Roman dinner party (cena). Cupid, now a husband, reclines in the place of honor (the "top" couch) and embraces Psyche in his lap. Jupiter and Juno situate themselves likewise, and all the other gods are arranged in order. The cupbearer of Jove (Jupiter's other name) serves him with nectar, the "wine of the gods"; Apuleius refers to the cupbearer only as ille rusticus puer, "that country boy," and not as Ganymede. Liber, the Roman god of wine, serves the rest of the company. Vulcan, the god of fire, cooks the food; the Horae ("Seasons" or "Hours") adorn, or more literally "empurple," everything with roses and other flowers; the Graces suffuse the setting with the scent of balsam, and the Muses with melodic singing. Apollo sings to his lyre, and Venus takes the starring role in dancing at the wedding, with the Muses as her chorus girls, a satyr blowing the aulos (tibia in Latin), and a young Pan expressing himself through the pan pipes (fistula).

The wedding provides closure for the narrative structure as well as for the love story: the mysteriously provided pleasures Psyche enjoyed in the domus of Cupid at the beginning of her odyssey, when she entered into a false marriage preceded by funereal rites, are reimagined in the hall of the gods following correct ritual procedure for a real marriage.[17] The arranging of the gods in their proper order (in ordinem) would evoke for the Roman audience the religious ceremony of the lectisternium, a public banquet held for the major deities in the form of statues arranged on luxurious couches, as if they were present and participating in the meal.[18]

The wedding banquet was a favored theme for Renaissance art. As early as 1497, Giovanni Sabadino degli Arienti made the banquet central to his now-lost Cupid and Psyche cycle at the Villa Belriguardo, near Ferrara. At the Villa Farnesina in Rome, it is one of two main scenes for the Loggia di Psiche (ca. 1518) by Raphael and his workshop, as well as for the Stanza di Psiche (1545–46) by Perino del Vaga at the Castel Sant' Angelo.[18] Hendrick Goltzius introduced the subject to northern Europe with his "enormous" engraving called The Wedding of Cupid and Psyche (1587, 43 by 85.4 cm),[19] which influenced how other northern artists depicted assemblies of the gods in general.[20] The engraving in turn had been taken from Bartholomaeus Spranger's 1585 drawing of the same title, considered a "locus classicus of Dutch Mannerism" and discussed by Karel Van Mander for its exemplary composition involving numerous figures.[21]

In the 18th century, François Boucher's Marriage of Cupid and Psyche (1744) affirmed Enlightenment ideals with the authority figure Jupiter presiding over a marriage of lovely equals. The painting reflects the Rococo taste for pastels, fluid delicacy, and amorous scenarios infused with youth and beauty.[22]

كأمثولة

The story of Cupid and Psyche was readily allegorized. In late antiquity, Martianus Capella (5th century) refashions it as an allegory about the fall of the human soul.[24] For Apuleius, immortality is granted to the soul of Psyche as a reward for commitment to sexual love. In the version of Martianus, sexual love draws Psyche into the material world that is subject to death:[25] "Cupid takes Psyche from Virtue and shackles her in adamantine chains".[26]

الأدب

In 1491, the poet Niccolò da Correggio retold the story with Cupid as the narrator.[27] John Milton alludes to the story at the conclusion of Comus (1634), attributing not one but two children to the couple: Youth and Joy. Shackerley Marmion wrote a verse version called Cupid and Psyche (1637), and La Fontaine a mixed prose and verse romance (1699).[27]

الفولكلور وأدب الأطفال

علم النفس والنسوية

الفنون الجميلة والزخرفية

الفن القديم

العصر الحديث

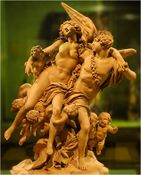

النحت

Cupid and Psyche (2nd century AD)

Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss (1793) by Antonio Canova

Cupid and Psyche by Clodion (d. 1814)

Psyche by Bertel Thorvaldsen (d. 1844)

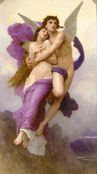

الرسم

Amor and Psyche (1589) by جاكوپو زوتشي

Amor and Psyche by لوي-جان-فرانسوا لاگرينيه (ت. 1805)

Allegory of Love, Cupid and Psyche by گويا (d. 1828)

Cupid and Psyche (1850–55) by كارولي بروكي

Cupid and Psyche (1843) by جان-پيير سانتور

Cupid and Psyche بريشة بنجامن وست رئيس الأكاديمية الملكية

Cupid and Psyche in the nuptial bower by Hugh Douglas Hamilton

The abduction of Psyche by William-Adolphe Bouguereau

Psyche Lifted Up by Zephyrs (Romantic, ca. 1800) by پيير-پول پرودون

Psyche (1890) by John Reinhard Weguelin

Psyche Opening the Golden Box (1903) by John William Waterhouse

See also

- Beauty and the Beast

- Graciosa and Percinet

- East of the Sun and West of the Moon

- Snow-White and Rose-Red

- Pride and Prejudice

Notes

- ^ Dorothy Johnson, David to Delacroix: The Rise of Romantic Mythology (University of North Carolina Press, 2011), pp. 81–87.

- ^ Lewis, C. S. (1956). Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 311. ISBN 0156904365.

- ^ Stephen Harrison, entry on "Cupid," The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), p. 338.

- ^ Hendrik Wagenvoort, "Cupid and Psyche," reprinted in Pietas: Selected Studies in Roman Religion (Brill, 1980), pp. 84–92 online.

- ^ Harrison, "Cupid and Psyche," in Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 339.

- ^ Harrison, "Cupid and Psyche," Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 338.

- ^ Entry on "Apuleius," in The Classical Tradition (Harvard University Press, 2010), pp. 56–57.

- ^ The following summary is condensed from the translation of Kenney (Cambridge University Press, 1990), and the revised translation of W. Adlington by S. Gaseless for the Loeb Classical Library (Harvard University Press, 1915), with reference to the accompanying Latin text.

- ^ Papaioannou, "Charite's Rape, Psyche on the Rock," p. 319.

- ^ Max Nelson, "Narcissus: Myth and Magic," Classical Journal 95.4 (2000), p. 364, citing S. Lancel, "Curiositas et préoccupations spirituelles chez Apulée," Revue de l'histoire des religions 160 (1961), pp. 41–45.

- ^ By the 6th-century mythographer Fulgentius; Joel C. Relihan, Apuleius: The Tale of Cupid and Psyche (Hackett, 2009), p. 65.

- ^ Cakes were often offerings to the gods, particularly in Eleusinian religion; cakes of barley meal moistened with honey, called prokonia (προκώνια), were offered to Demeter and Kore at the time of first harvest. See Allaire Brumfield, “Cakes in the liknon: Votives from the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore on Acrocorinth,” Hesperia 66 (1997) 147–172.

- ^ Apuleius describes it as served in a cup, though ambrosia is usually regarded as a food and nectar as a drink.

- ^ Philip Hardie, Rumour and Renown: Representations of Fama in Western Literature (Cambridge University Press, 2012), p. 116; Papaioannou, "Charite's Rape, Psyche on the Rock," p. 321.

- ^ Relihan, The Tale of Cupid and Psyche, p. 79.

- ^ Stephen Harrison, "Divine Authority in 'Cupid and Psyche': Apuleius Metamorphoses 6,23–24," in Ancient Narrative: Authors, Authority, and Interpreters in the Ancient Novel. Essays in Honor of Gareth L. Schmeling (Barkhuis, 2006), p. 182.

- ^ Harrison, "Divine Authority in 'Cupid and Psyche'," p. 179.

- ^ أ ب Harrison, "Divine Authority in 'Cupid and Psyche'," p. 182.

- ^ Ariane van Suchtelen and Anne T. Woollett, Rubens and Brueghel: A Working Friendship (Getty Publications, 2006), p. 60; Susan Maxwell, The Court Art of Friedrich Sustris: Patronage in Late Renaissance Bavaria (Ashgate, 2011), pp. 172, 174.

- ^ Van Suchtelen and Woollett, Rubens and Brueghel, p. 60; Maxwell, The Court Art of Friedrich Sustris, p. 172.

- ^ Martha Hollander, An Entrance for the Eyes: Space and Meaning in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art (University of California Press, 2002), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Michelle Facos, An Introduction to 19th Century Art (Routledge, 2011), p. 20.

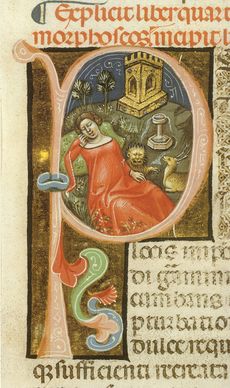

- ^ Manuscript Vat. Lat. 2194, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

- ^ Danuta Shanzer, A Philosophical and Literary Commentary on Martianus Capella's De Nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii Book 1 (University of California Press, 1986), p. 69.

- ^ Relihan, The Tale of Cupid and Psyche, p. 59.

- ^ Martianus Capella, De Nuptiis 7; Chance, Medieval Mythography, p. 271.

- ^ أ ب Entry on "Apuleius," Classical Tradition, p. 57.

- ^ "Sarcophagus panel: Cupid and Psyche", Indianapolis Museum of Art description. The sarcophagus was made for retail, and the portrait added later.

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=1D6wUrxqcRIC&pg=PA141

- ^ http://www.nationalgeographic.com/mission/afghanistan-treasures/

- ^ http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/news/looted-afghan-treasures-identified-2229207.html?action=gallery&ino=13

References

- Malcolm Bull, The Mirror of the Gods, How Renaissance Artists Rediscovered the Pagan Gods, pp. 342–343, Oxford UP, 2005, ISBN 978-0195219234

- Anita Callaway, Visual Ephemera: Theatrical Art in Nineteenth-Century Australia (University of New South Wales Press, 2000)

- Stephen Harrison, "Divine Authority in 'Cupid and Psyche': Apuleius Metamorphoses 6,23–24," in Ancient Narrative: Authors, Authority, and Interpreters in the Ancient Novel. Essays in Honor of Gareth L. Schmeling (Barkhuis, 2006)

وصلات خارجية

- Tales Similar to Beauty and the Beast (Texts of Cupid and Psyche and similar monster or beast as bridegroom tales, mostly of AT-425C form, with hyperlinked commentary).

- Robert Bridge's Eros and Psyche at archive.org: pdf or read online

- Mary Tighe, Psyche or, the Legend of Love (1820) HTML or PDF

- Walter Pater, Marius the Epicurean, chapter 5 (1885)

- Thomas Bulfinch, The Age of Fable (1913)

- Hermetic Philosophy: Cupid and Psyche (Illustrated with painting and sculpture.)

- [1] "Cupid and Psyche ~ A New Play in Blank Verse"

- [2] Turn to Flesh Productions

- The Labors of Psyche: Toward a Theory of Female Heroism by Lee R. Edwards

- Art

- Art Renewal Center: "Cupid & Psyche" by Sharrell E. Gibson (Examples and discussion of Cupid and Psyche in painting.)

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (ca 430 images of Cupid and Psyche)

- Tale of Cupid and Psyche engravings by Maestro del Dado and Agostino Veneziano from the De Verda collection