الحقبة الجميلة البرازيلية

| Brazilian Belle Époque | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870–1922 | |||

The Brazilian Centennial Exhibition of 1922 | |||

| ويضم | |||

| الزعيم | Pedro II, Campos Sales, Rodrigues Alves, Afonso Pena, Epitácio Pessoa | ||

| |||

The Brazilian Belle Époque, also known as the Tropical Belle Époque or Golden Age, is the South American branch of the French Belle Époque movement (1871-1914), based on the Impressionist and Art Nouveau artistic movements. It occurred between 1870 and February 1922 (between the last years of the Brazilian Empire and the Modern Art Week) and involved a cosmopolitan culture, with changes in the arts, culture, technology and politics in Brazil.[1]

The Belle Époque in Brazil differs from other countries, both in the duration and the technological advance, and happened mainly in the country's most prosperous regions at the time: the rubber cycle area (Amazonas and Pará), the coffee-growing area (São Paulo and Minas Gerais) and the three main colonial cities (Recife, Rio de Janeiro and Salvador).[1][2]

History

Amazonas and Pará

Financed by rubber, the Belle Époque of the Northern region began in 1871, mainly centred on the cities of Belém (capital of the state of Pará) and Manaus (capital of the state of Amazonas), known as the Paris of the Tropics or Paris n'America, and was a period marked by intensive modernization of both cities.[3][4][5]

Between 1890 and 1920, Belém and Manaus were among the most developed and prosperous cities in the world, with technologies that other areas of the country did not yet have, including boulevards, squares, parks, markets, health policies, public transportation and lighting.[3][6][7]

Both had electricity, running water, a sewage system, electric streetcars and avenues over landfilled marshes. In Belém, great architectural works appeared, such as the São Brás Market, the Francisco Bolonha Market, the Ver-o-Peso Market, the Antônio Lemos Palace, the Cine Olympia (the oldest in Brazil in operation), the Grande Hotel, the Bolonha Mansion and several residential palaces, built in large part by the intendant Antônio Lemos.[8] Another attraction in the city is the Theatro da Paz, which was the meeting place for Belém's elite who, dressed in Parisian fashion, attended the inauguration to the sound of musical chords in a splendid, refined and lively atmosphere.[9][7][3]

Manaus underwent a radical transformation: the local rulers and merchants brought hundreds of architects, urban planners, landscapers and artists from Europe, whose mission was implementing an ambitious urban plan, which resulted in a city with a European-influenced architectural profile. The extraction of rubber financed the construction of buildings, electric streetcars, a telephone network, piped water and a large floating port.[10] Manaus was one of the first Brazilian cities to have electricity and water and sewage treatment services.[11] The Provincial Palace was built in 1875, the Metropolitan Cathedral in 1877, the Adolpho Lisboa Municipal Market in 1883, the Church of Saint Sebastian in 1888 and the Benjamin Constant Bridge in 1895, all designed by English engineers. In 1896, already equipped with electricity, Manaus inaugurated the luxurious Amazon Theatre, designed by the elite of the city who wanted to bring Manaus culturally closer to the French capital (at the time, the city was nicknamed the Paris of the Tropics).[4][12] The Palace of Justice was built in 1900, the Manaus Customs House in 1909, the Amazonas Public Library in 1910 and the Rio Negro Palace in 1911, among others. At the time, it had around 50,000 inhabitants.[13]

The extraction of rubber, which accounted for 40% of Brazilian exports, gave Belém and Manaus an era of prosperity, making them among the richest cities in Brazil at the time. The currency used in rubber transactions, which circulated in Manaus and Belem during the Brazilian Belle Époque, was the pound sterling (currency of the United Kingdom).[14][6][15]

Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo

In the Southeast, the Belle Époque reflects the golden age that coffee brought to the cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, establishing themselves as a national economic center.[16]

At the end of the 19th century, there were profound social changes in Rio de Janeiro's urban landscape. The arrival of immigrants in 1875 after the construction of the Central do Brasil, of several homeless soldiers from the Canudos War in 1897 and of former slaves from the Paraíba Valley after the abolition of slavery in 1888, increased the city's population from 266,000 to 730,000 between 1872 and 1904. As a result, tenements and favelas began to develop in the hills around the city center, leading to the creation of Rio de Janeiro's first favela, the Morro da Providência, in 1897. According to the IBGE, Rio de Janeiro's population reached 1,157,873 in 1920.[17][18][13]

Inspired by Haussmann's reforms, Mayor Pereira Passos conducted a radical urban reform in Rio de Janeiro with the purpose of sanitizing, urbanizing, embellishing and, consequently, giving the city a modern and cosmopolitan appearance. To increase air circulation in the center of Rio, many streets were widened or opened up, such as Floriano Peixoto Street and Rio Branco Avenue, respectively. The historic Morro do Castelo, where Mem de Sá had re-founded the city in 1567 with the installation of the São Sebastião Fortress, the town hall and jail, the governor's house and the warehouses-general, was dismantled. The city also gained numerous streetcar lines.[19] In 1908, the National Exhibition of the 1st Centenary of the Opening of Brazil's Ports was held in Urca, for which several temporary buildings were constructed. Most of these structures were demolished after the end of the exhibition, with the exception of the States Pavilion building, now occupied by the Earth Sciences Museum.[20][21]

Another important element was the creation of middle-class areas in Rio, such as those in the Greater Méier region, and wealthy neighborhoods, such as Glória, Catete, Botafogo and Copacabana, which were permanently occupied with the opening of the Alaor Prata Tunnel.[22] The Sugarloaf Cable Car was also created during this period, in 1912.[23]

In 1897, José Roberto da Cunha Salles directed Ancoradouro de Pescadores na Baía de Guanabara, considered to be the first film in the history of Brazilian cinema.[24] In 1909, the Municipal Theater of Rio de Janeiro, one of the greatest symbols of the Belle Époque in the city, was inaugurated. Later, the entire Cinelândia complex, where the theater is located, was reconfigured with the installation of the Monroe Palace and several cinemas (Cine Odeon, Cineac Trianon, Parisiense, Império, Pathé, Capitólio, Rex, Rivoli, Vitória, Palácio, Metro Passeio, Plaza and Colonial).[25][26]

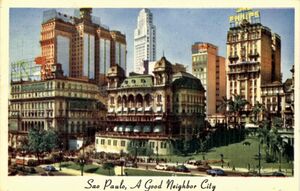

The new aesthetic also stimulated the remodeling of Rio's traditional leisure centers such as Casa Cavé and Confeitaria Colombo, still considered one of the ten most beautiful coffee houses in the world, as well as the flourishing of rhythms such as choro and samba.[27] Sophisticated hotels such as the Copacabana Palace Hotel, the Glória Hotel and the Balneário Hotel (which later became better known for housing the famous Urca Casino) were inaugurated for the Independence Centenary International Exposition.[28][29] On September 7, 1929, the Joseph Gire Building, the first skyscraper in Brazil, was inaugurated. As a result of all these transformations, in 1928 the journalist and writer from Maranhão, Coelho Neto, described the city in short stories as "A Cidade Maravilhosa" (English: The Marvelous City), a nickname that inspired the carnival march of the same name, composed in 1934 by Antônio André de Sá Filho.[30] In São Paulo, during the First Brazilian Republic (1889-1930), the city industrialized and the population increased from around 70,000 in 1890 to 240,000 in 1900 and 580,000 in 1920. The peak of the coffee period is represented by the construction of the second Luz Station (the current building) at the end of the 19th century and by the Paulista Avenue in 1900, where many mansions were built.[31][32]

The Anhangabaú Valley was landscaped and the area on its left bank was renamed Centro Novo (English: New Center). At the beginning of the 20th century, the seat of the São Paulo government was moved from the Pátio do Colégio to Campos Elísios. In 1922, São Paulo hosted the Modern Art Week, a milestone in the history of art in Brazil. In 1929, the city got its first skyscraper, the Martinelli Building.[33][34] The changes made to the city by Antônio da Silva Prado, the Baron of Duprat, and Washington Luís, who governed from 1899 to 1919, contributed to the feeling of development in São Paulo; some scholars consider that the entire city was demolished and rebuilt during that period.[16]

In the 20th century, with the industrial growth of São Paulo, which also contributed to the difficulties of access to imports during the World War I, the urbanized area of the city began to increase, and some residential neighborhoods were built in areas that used to be farmland.[16] From the 1920s onwards, with the straightening of the course of the Pinheiros River and the conversion of its waters to supply the Henry Borden Hydroelectric Power Station, the flooding in the areas surrounding the river ceased, allowing the emergence of prestigious residential properties on the west side of São Paulo, known today as the Jardins. The principal symbol of the Belle Époque in São Paulo and also in Brazil is the Municipal Theatre of São Paulo.[35][36]

São Paulo developed due to its privileged location at the center of the coffee complex and its proximity to the Port of Santos.[37] The intensive immigration to the city is mainly due to the cultural diversity of the place, greatly influenced by Italians and the mixture of different Brazilian regions. The city also has neighborhoods that are home to immigrant colonies, such as Liberdade, which is the seat of the largest Japanese colony outside Japan, and Bixiga, a refuge of Italian immigrants in the city.[38][39]

Culture

The Republic, installed in 1889, wanted to launch a new era in Brazil; to this end, it sought to minimize everything that was reminiscent of the Empire and Portuguese colonization. The arts took a new direction, moving closer to French and Italian cultures. This period witnessed the foundation of Belo Horizonte, a planned city, and the major urban reforms implemented in Rio de Janeiro, then the Federal Capital, by Pereira Passos and Rodrigues Alves.[40][41]

The period was also characterized by strong moralism and sexual repression, which were typical of the Victorian era.[42] The monetary unit in force in Brazil was still the réis, a standard instituted by the Portuguese in colonial times. In terms of the Portuguese language, the spelling rules obeyed the dictates of Greek and Latin. This way of writing only came to an end with the spelling reform of 1943, during the Vargas era; farmácia (pharmacy) and comércio (commerce), for example, were spelled pharmacia and commercio.[43]

The ufanistic atmosphere of the time resulted in foreign words being translated into Portuguese. An example of this was with futebol (soccer), a recent phenomenon in the country, where an attempt was made to rename it ludopédio, where ludo = jogo (game) and pédio = pé (foot), or bola no pé (ball on foot).[44]

Revolts

There were several revolts during the Brazilian Belle Époque:

- Federalist Revolution, Rio Grande do Sul;[45]

- Vaccine Revolt, Rio de Janeiro;[46]

- Caldeirão de Santa Cruz do Deserto, Ceará;[47]

- Prestes Column, all of Brazil;[48]

- Manaus Commune, Amazonas;[49]

- Canudos War, Bahia;[50]

- Contestado War, Santa Catarina and Paraná;[51]

- Republic of Independent Guiana, Amapá;[52]

- Brazilian Naval Revolts, Rio de Janeiro;[53]

- Revolt of the Lash, Rio de Janeiro;[54]

- Copacabana Fort Revolt, Rio de Janeiro;[55]

- São Paulo Revolt of 1924, São Paulo;[56]

- Acre Revolution, Acre;[57]

- Revolution of 1923, Rio Grande do Sul;[58]

- Juazeiro Sedition, Bahia;[59]

End of the era

The Brazilian Belle Époque ended in 1922, with the Modern Art Week, the founding of the PCB and the tenentist rebellions. However, the presence of this style of culture didn't disappear all at once, but gradually. Its influence was felt until the early 30s.[1]

See also

References

- ^ أ ب ت Lima, Natália Dias de Casado. "A Belle Époque e seus reflexos no Brasil". UFES.

- ^ Alchorne, Murilo de Avelar (2014). "Porto do Recife: d'África à des'África. Joaquim Nabuco, Gilberto Freyre e Mário Sette sobre raça e urbanização, no Recife de Belle Époque". UFPE. 20. Retrieved 2019-12-27.

- ^ أ ب ت "Exposição mostra prédios em formato digital". Diário Online. 2014-04-01. Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- ^ أ ب Cotta, Carolina (2015-04-22). "A Paris dos Trópicos: conheça os requintados tesouros de Manaus". Correio Braziliense. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- ^ "Um fragmento da Amazônia no coração de Belém". Agência Belém de Notícias. 2017-01-12. Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- ^ أ ب Nogueira, André (2019-03-22). ""BELLE EPOQUE" DA AMAZÔNIA: POR DÉCADAS AS CAPITAIS DO NORTE ERAM AS MAIS DESENVOLVIDAS". Aventuras na História. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- ^ أ ب Soares, Karol Gillet. "AS FORMAS DE MORAR NA BELÉM DA BELLE-ÉPOQUE (1870-1910)" (PDF). UFPA.

- ^ "Ver-o-Peso (PA)". IPHAN.

- ^ "Cine Olympia comemora 103 anos com programação especial em Belém". G1. 2015-04-21. Retrieved 2017-10-10.

- ^ "Ciclo da borracha mudou capital". Folha de S. Paulo. 1998-04-13. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- ^ Rivera, Karina (2018-01-30). "Manaus: uma capital cheia de história para contar". Estadão. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- ^ "Energia elétrica completa 120 anos em Manaus". Rede Tiradentes. 2016-11-03. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ أ ب "Estatísticas do séc. XX". IBGE. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Riqueza da borracha levou sofisticação a Manaus". Globo Reporter. 2011-10-24. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- ^ Curado, Adriano (2020-01-12). "Como o ciclo da Borracha levou prosperidade para o norte do Brasil". R7. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- ^ أ ب ت Doin, José Evaldo de Mello; PErinelli Neto, Humberto; Paziani, Rodrigo Ribeiro; Pacano, Fábio Augusto (2007). "A Belle Époque caipira: problematizações e oportunidades interpretativas da modernidade e urbanização no Mundo do Café (1852-1930)". Dossiê: Cidades. 27 (53).

- ^ Carvalho, Janaina (2015-01-12). "Conheça a história da 1ª favela do Rio, criada há quase 120 anos". G1. Retrieved 2018-05-28.

- ^ "Imigração no Brasil". Brasil Escola. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Reforma Urbanística de Pereira Passos, o Rio com cara de Paris". G1. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Série "O Rio de Janeiro desaparecido" II – A Exposição Nacional de 1908 na Coleção Família Passos". Brasiliana Fotografica. 2018-04-05. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Série "O Rio de Janeiro desaparecido" VIII – A demolição do Morro do Castelo". Brasiliana Fotografica. 2019-04-30.

- ^ Santos, Sergio Roberto Lordello (1981). "Expansão urbana e estruturação de bairros do Rio de Janeiro" (PDF). UFRJ.

- ^ "Inaugurado o Bondinho do Pão de Açúcar". Ensinar História. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ Couto, José Geraldo (1995-11-30). ""Lumière" brasileiro também era médico, bicheiro e dramaturgo". Folha de S. Paulo. Retrieved 2020-05-13.

- ^ Bittar, William (2023-07-12). "Theatro Municipal do Rio de Janeiro, 114 anos: a síntese da Belle-Époque no Plano Passos". Diario do Rio. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "CINEL NDIA E O PROJETO DA BROADWAY BRASILEIRA". Viajando pela História. 2022-07-24. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "THE 10 MOST BEAUTIFUL CAFÉS IN THE WORLD". UCity Guides. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ^ Tokarnia, Mariana (2023-08-13). "Copacabana Palace completa 100 anos apostando em luxo com tradição". Agencia Brasil. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ Nepomuceno, Nina Zonis (2021). "GRANDES HOTÉIS CENTRAIS NO RIO DE JANEIRO (1908-1922)" (PDF). UFRJ.

- ^ Silva, Fabio Henrique Monteiro (2014-12-02). "Do carnaval carioca à invenção da carioquização do carnaval de São Luis". UFRJ.

- ^ Cordeiro, Simone Lucena (2005-04-01). "Moradia Popular Na Cidade De São Paulo".

- ^ "Marco da capital paulista, Estação da Luz completa 120 anos". 2021-03-01. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ Coelho, Yeska (2022-02-14). "Semana de Arte Moderna de 22 completa 100 anos, mas o que foi o evento?". CasaCor. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "A história de Martinelli, o imigrante que sonhou subir aos céus". São Paulo City Hall. 27 July 2006. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ Oliveira, Abrahão (2013-04-29). "O Símbolo da "Belle Époque" Paulistana: O Theatro Municipal de São Paulo". São Paulo CIty Hall. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Jardim Paulistano: Um guia sobre um dos bairros mais nobres de São Paulo". GVCB. 2021-09-15. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ Sales, Pedro Manuel Rivaben de (1999). "Jardim Paulistano: Um guia sobre um dos bairros mais nobres de São Paulo" (PDF). USP.

- ^ "6 países com a maior comunidade japonesa fora do Japão". Mundo Nipo. 2019-03-07. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ Leite, Sylvia (2020-05-17). "Bixiga: um pedaço de São Paulo que abriga gente de toda parte". Lugares de Memoria. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ Barbosa, Maria Ignez (2010-04-04). "A vida na belle époque carioca". Estadão.

- ^ Zanon, Maria Cecilia (4 August 2007). "A sociedade carioca da Belle Époque nas páginas do nas páginas do Fon-Fon!". Patrimônio e Memória. 4 (2): 217–235.

- ^ "Belle Époque". Significados. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Formulário Ortográfico de 12 de agosto de 1943". Ato Comunicacional. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Ludopédio, o jogo do Chico". Almanaque do Malu. 2010-04-27. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Revolução Federalista". UOL. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ Dandara, Luana (2022-06-09). "Cinco dias de fúria: Revolta da Vacina envolveu muito mais do que insatisfação com a vacinação". Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Caldeirão de Santa Cruz do Deserto, o massacre que o Brasil não viu". Catraca Livre. 2020-11-22. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "O que foi a Coluna Prestes?". Brasil Escola. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ Santos, Thamires (2020-11-26). "COMUNA DE MANAUS". Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Guerra de Canudos". UOL. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Guerra do Contestado". Brasil Escola. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ Leão, Ricardo (2021-07-23). "História do Amapá – A República do Cunani (ou Counani)". Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Revolta da Armada". UOL. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Revolta da Chibata". Brasil Escola. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Revolta do Forte de Copacabana". Toda Matéria. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Revolta Paulista de 1924". Brasil Escola. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Revolução Acreana". Toda Matéria. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Centenário da Revolução de 1923 é o tema dos Festejos Farroupilhas 2023". 2023-03-28. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

- ^ "Sedição de Juazeiro". FGV. Retrieved 2023-08-30.

Bibliography

- Ermakoff, George (2003). Rio de Janeiro 1900 - 1930: Uma crônica fotográfica. G. Ermakoff.

- Ermakoff, George (2009). Augusto Malta e o Rio de Janeiro - 1903-1936. G. Ermakoff.

- Nosso Século. Abril Cultural. 1980.

- Requena, Brian Henrique de Assis Fuentes (2014). "A formação do campo literário na Belle Époque brasileira". Revista Pessoa.

- Visconti, Tobias Stourdzé (2012). Eliseu Visconti - A arte em movimento. Holos Consultores Associados.