معركة خليج مانيلا

| Battle of Manila Bay | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جزء من the Spanish–American War | |||||||

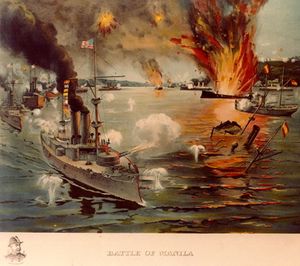

Contemporary colored print, showing يوإسإس Olympia in the left foreground, leading the U.S. Asiatic Squadron against the Spanish fleet off Cavite. A vignette portrait of Rear Admiral George Dewey is featured in the lower left. | |||||||

| |||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| القوى | |||||||

|

Engaged forces:[cn 1] 4 protected cruisers 2 gunboats Unengaged forces: 1 revenue cutter 2 transports |

Engaged forces:[cn 1] 2 protected cruisers 4 unprotected cruisers 2 gunboats Unengaged forces: 1 cruiser 3 gunboats, 1 transport Shore defenses 6 batteries 3 forts | ||||||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||||||

|

1 dead (due to heatstroke),[5] and 9 wounded 1 protected cruiser damaged |

77 dead and 271 wounded[6] 2 protected cruisers sunk, 5 unprotected cruisers sunk, 1 transport sunk | ||||||

قالب:Campaignbox Spanish-American War: Pacific

The Battle of Manila Bay (إسپانية: Batalla de Bahía de Manila), also known as the Battle of Cavite, took place on 1 May 1898, during the Spanish–American War. The American Asiatic Squadron under Commodore George Dewey engaged and destroyed the Spanish Pacific Squadron under Contraalmirante (Rear admiral) Patricio Montojo. The battle took place in Manila Bay in the Philippines, and was the first major engagement of the Spanish–American War. The battle was one of the most decisive naval battles in history and marked the end of the Spanish colonial period in Philippine history.[7]

Prelude

Americans living on the West Coast of the United States feared a Spanish attack at the outbreak of the Spanish–American War. Only a few U.S. Navy warships, led by the cruiser يوإسإس Olympia, stood between them and a powerful Spanish fleet.[7]

Admiral Montojo, a career Spanish naval officer who had been dispatched rapidly to the Philippines, was equipped with a variety of obsolete vessels. Efforts to strengthen his position amounted to little. The strategy adopted by the Spanish bureaucracy suggested they could not win a war and saw resistance as little more than a face-saving exercise.[8] Administration actions worked against the effort, sending explosives meant for naval mines to civilian construction companies while the Spanish fleet in Manila was seriously undermanned by inexperienced sailors who had not received any training for over a year.[9] Reinforcements promised from Madrid resulted in only two poorly-armored scout cruisers being sent while at the same time the authorities transferred a squadron from the Manila fleet under Admiral Pascual Cervera to reinforce the Caribbean. Admiral Montojo had originally wanted to confront the Americans at Subic Bay, northwest of Manila Bay, but abandoned that idea when he learned the planned mines and coastal defensives were lacking and the cruiser Castilla started to leak.[8] Montojo compounded his difficulties by placing his ships outside the range of Spanish coastal artillery (which might have evened the odds) and choosing a relatively shallow anchorage. His intent seems to have been to spare Manila from bombardment and to allow any survivors of his fleet to swim to safety. The harbor was protected by six shore batteries and three forts whose fire during the battle proved to be ineffective. Only Fort San Antonio Abad had guns with enough range to reach the American fleet, but Dewey never came within their range during the battle.[3][9]

The Spanish squadron consisted of seven ships: the cruisers Reina Cristina (flagship), Castilla, Don Juan de Austria, Don Antonio de Ulloa, Isla de Luzon, Isla de Cuba, and the gunboat Marques del Duero. The Spanish ships were of inferior quality to the American ships; the Castilla was unpowered and had to be towed by the transport ship Manila.[10] On April 25, the squadron left Manila Bay for the port of Subic, intending to mount a defense there. The squadron was relying on a shore battery which was to be installed on Isla Grande. On April 28, before that installation could be completed, a cablegram from the Spanish Consul in Hong Kong arrived with the information that the American squadron had left Hong Kong bound for Subic for the purpose of destroying the Spanish squadron and intending to proceed from there to Manila. The Spanish Council of Commanders, with the exception of the Commander of Subic, felt that no defense of Subic was possible with the state of things, and that the squadron should transfer back to Manila, positioning in shallow water so that the ships could be run aground to save the lives of the crews as a final resort. The squadron departed Subic at 10:30 a.m. on 29 April. Manila, towing Castilla, was last to arrive in Manila Bay, at midnight.[11]

See also

- Battle of Manila (disambiguation)

- Battles of the Spanish–American War

- Philippine–American War

- List of naval battles

Notes

- ^ أ ب Accounts of the numbers of vessels involved vary. Admiral Dewey said, "The Spanish line of battle was formed by the Reina Cristina (flag), Castilla, Don Juan de Austria, Don Antonio de Ulloa, Isla de Luzon, Isla de Cuba, and Marques del Duero."[1] Another source lists the order of battle as consisting of nine U.S. ships (two not engaged) and 13 Spanish ships (five not engaged and one not present).[2] Still another source says that the Spanish naval force consisted of seven unarmored ships.[3] Yet another source says that Dewey's squadron included four cruisers (two armored), two gunboats, and one revenue cutter; and that the Spanish fleet consisted of one modern cruiser half the size of Dewey's Olympia, one old wooden cruiser, and five gunboats.[4]

References

- ^ According to an article titled "The Battle of Manila Bay", written by Admiral Dewey for the War Times Journal, his actual words were, "You may fire when you are ready, Gridley.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةships - ^ Symonds, Craig L.; Clipson, William J. (2001). The Naval Institute historical atlas of the U.S. Navy. Naval Institute Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-55750-984-0.

- ^ Brinkley, Alan (1995). American History: A Survey. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-912114-4.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRodriguezG - ^ أ ب "Historic Ships on a Lee Shore". Sea History. National Maritime Historical Society (144): 12–13. August 2013.

- ^ أ ب Nofi, A.A., 1996, The Spanish–American War, 1898, Pennsylvania: Combined Books, ISBN 0938289578

- ^ أ ب Koenig, William (1975). Epic Sea Battles. Page 102–119: Peerage Books. ISBN 0-907408-43-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Saravia & Garcia 2003, pp. 12–13, 27, 29

- ^ Saravia & Garcia 2003, pp. 27–29

Additional References

- Nofi, Albert A., The Spanish American War, 1898, 1997.

- Carrasco García, Antonio, En Guerra con Los Estados Unidos: Cuba, 1898, Madrid: 1998.

- Freidel, Frank Burt. The Splendid Little War. Boston: Little, Brown, 1958.

- Blow, Michael. A Ship to Remember: The Maine and the Spanish–American War. New York : Morrow, 1992. ISBN 0-688-09714-6.

- Saravia, José Roca de Togores y; Garcia, Remigio (2003), Blockade and Siege of Manila in 1898, National Historical Institute, ISBN 978-971-538-167-3, https://books.google.com/books?id=lhZ3AAAAMAAJ

وصلات خارجية

- Spanish–American War Centennial Website

- 1898 Battle of Manila Bay (archived from the original on 2009-10-26)

- Alejandro Anca Alamillo, Investigador Naval (in Spanish), Batalla de Cavite (1 de mayo de 1898), Revista Naval (Naval review), http://www.revistanaval.com/armada/batallas/cavite.htm, retrieved on 10 October 2007

- CS1 maint: location

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Articles containing إسپانية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Naval battles of the Spanish–American War

- Conflicts in 1898

- Philippine–American War

- History of Manila

- United States Marine Corps in the 18th and 19th centuries

- Manila Bay

- May 1898 events