حوليات الخيزران

| |

| العنوان الأصلي | 竹書紀年 |

|---|---|

| البلد | دولة وِيْ، الصين القديمة |

| اللغة | الصينية التقليدية |

| الموضوع | التاريخ الصيني القديم |

تاريخ النشر | قبل 296 ق.م. |

| حوليات الخيزران | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الصينية التقليدية | 竹書紀年 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الصينية المبسطة | 竹书纪年 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| المعنى الحرفي | "حوليات كتابات الخيزران" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

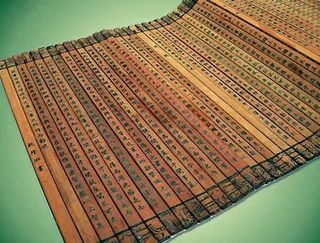

حوليات الخيزران (Chinese: 竹書紀年; pinyin: Zhúshū Jìnián؛ إنگليزية: Bamboo Annals)، وتُعرف أيضاً بإسم حوليات مقابر جي (Chinese: 汲冢紀年; pinyin: Jí Zhǒng Jìnián؛ إنگليزية: Ji Tomb Annals)، هي تأريخ للصين القديمة. وتبدأ في أقدم الأزمنة الأسطورية (الامبراطور الأصفر) وتمتد إلى 299 ق.م.، مع تركيز القرون اللاحقة على تاريخ دولة وِيْ في فترة الدويلات المتناحرة. وبذلك فهي تغطي فترة مشابهة لعمل سيما چيان، سجلات المؤرخ العظيم (91 ق.م.). ولعل الأصل قد فـُقِد أثناء أسرة سونگ،[1] والنص المعروف اليوم في نسختين، "نص حالي" (أو "نص معاصر") ذو أصلية مشكوك فيها و"نص قديم" غير كامل.

التاريخ النصي

النص الأصلي دُفِن مع الملك شيانگ من وِيْ (توفي 296 ق.م.) and re-discovered nearly six centuries later in 281 AD (Western Jin dynasty) in the Jizhong discovery. For this reason, the chronicle survived the burning of the books by Emperor Qin Shi Huang. Other texts recovered from the same tomb included Guoyu, I Ching, and the Tale of King Mu. They were written on bamboo slips, the usual writing material of the Warring States period, and it is from this that the name of the text derives.[2] The strips were arranged in order and transcribed by court scholars, who identified the work as the state chronicle of Wei. According to Du Yu, who saw the original strips, the text began with the Xia dynasty, and used a series of different pre-Han calendars. However, later indirect reports state that it began with the Yellow Emperor. This version, consisting of 13 scrolls, was lost during the Song dynasty.[2][3] A 3-scroll version of the Annals is mentioned in the History of Song (1345), but its relationship to the other versions is not known.[4]

The "current text" (今本 jīnběn) is a 2-scroll version of the text printed in the late 16th century.[5][6] The first scroll contains a sparse narrative of the pre-dynastic emperors (beginning with the Yellow Emperor), the Xia dynasty and the Shang dynasty. The narrative is interspersed with longer passages on portents, which are identical to passages in the late 5th century Book of Song. The second scroll contains a more detailed account of the history of the Western Zhou, the state of Jin and its successor state Wei, and has no portent passages.[7] This version gave years according to the sexagenary cycle, a practice that began in the Han dynasty.[3] Discrepancies between the text and quotations of the earlier text in older books led scholars such as Qian Daxin and Shinzō Shinjō to dismiss the "current" version as a forgery,[8] a view still widely held.[9][10] Other scholars, notably David Nivison and Edward Shaughnessy, argue that substantial parts of it are faithful copies of the original text.[11]

The "ancient text" (古本 gǔběn) is a partial version assembled through painstaking examination of quotations of the lost original in pre-Song works by Zhu Youzeng (late 19th century), Wang Guowei (1917) and Fan Xiangyong (1956). Fang Shiming and Wang Xiuling (1981) have systematically collated all the available quotations, instead of following earlier scholars in trying to merge variant forms of a passage into a single text.[12][13] The two works that provide the most quotations, the Shui Jing Zhu (527) and Sima Zhen's Shiji Suoyin (early 8th century), seem to be based on slightly different versions of the text.[14]

الترجمات

- (بالفرنسية) Biot, Édouard (1841–42). "Tchou-chou-ki-nien, Annales de bambou Tablettes chronologiques du Livre écrit sur bambou", Journal asiatique, Third series, 12, pp. 537–78, and 13, pp. 203–207, 381–431.

- Legge, James (1865). "The Annals of the Bamboo Books", in "Prolegomena", The Chinese Classics, volume 3, part 1, pp. 105–188. Rpt. (1960) Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Nivison, David (2009). The Riddle of the Bamboo Annals (Zhushu Jinian Jiemi 竹書紀年解謎). Taipei: Airiti Press.

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

الهامش

- ^ Knechtges (2014), p. 2343.

- ^ أ ب Keightley (1978), p. 423.

- ^ أ ب Nivison (1993), pp. 40–41.

- ^ Shaughnessy (2006), p. 193.

- ^ Nivison (1993), pp. 41, 44.

- ^ Shaughnessy (2006), pp. 193–194.

- ^ Nivison (1993), p. 40.

- ^ Nivison (1993), pp. 39, 42–43.

- ^ Keightley (1978), p. 424.

- ^ Barnard (1993), pp. 50–69.

- ^ Shaughnessy (1986).

- ^ Keightley (1978), pp. 423–424.

- ^ Shaughnessy (2006), p. 209.

- ^ Shaughnessy (2006), pp. 210–222.

المصادر

- Works cited

- Barnard, Noel (1993), "Astronomical data from ancient Chinese records: the requirements of historical research methodology", East Asian History 6: 47–74, http://www.eastasianhistory.org/sites/default/files/article-content/06/EAH06%20_03.pdf.

- Keightley, David N. (1978), "The Bamboo Annals and Shang-Chou Chronology", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 38 (2): 423–438.

- Knechtges, David R. (2014). "Zhushu jinian 竹書紀年 (Bamboo Annals)". In Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping (eds.). Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide, Part Four. Leiden: Brill. pp. 2342–48. ISBN 978-90-04-27217-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nivison, David S. (1993), "Chu shu chi nien 竹書紀年", in Loewe, Michael, Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide, Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China, pp. 39–47, ISBN 1-55729-043-1.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1986), "On The Authenticity of the Bamboo Annals", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 46 (1): 149–180. reprinted in Shaughnessy, Edward L. (1997). Before Confucius. Studies in the Creation of the Chinese Classics. Ithaca: SUNY Press. pp. 69–101. ISBN 0-7914-3378-1.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. (2006), "The Editing and Editions of the Bamboo Annals", Rewriting Early Chinese Texts, Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 185ff, ISBN 978-0-7914-6644-5.

للاستزادة

- Nivison, David S. (1983), "The Dates of Western Chou", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 43 (2): 481–580.

- Nivison, David S. (1999), "The Key to the Chronology of the Three Dynasties. The 'Modern Text' Bamboo Annals", Sino-Platonic Papers 93, http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp093_bamboo_annals.pdf. (summary).

- Nivison, David S. (2009), The Riddle of the Bamboo Annals, Taipei: Airiti Press, ISBN 978-986-85182-1-6. (summary)

- Nivison, David S. (2011), "Epilogue to The Riddle of the Bamboo Annals", Journal of Chinese Studies 53: 1–32, http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/ics/journal/articles/v53p001.pdf. (responding to Shaughnessy (2011))

- Shao, Dongfang (邵東方) (2010) (in Chinese), Zhúshū jìnián yánjiū lùngǎo, Taipei: Airiti Press, ISBN 978-986-85182-9-2.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. (2011), "Of Riddles and Recoveries: The Bamboo Annals, Ancient Chronology, and the Work of David Nivison", Journal of Chinese Studies 52: 269–290, http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/ics/journal/articles/v52p269.pdf. (review of Nivison (2009))

وصلات خارجية

- Bamboo Annals at the Chinese Text Project.