أندرياس ليبافيوس

Andreas Libavius or Andrew Libavius was born in Halle, Germany ح. 1550 and died in July 1616. Libavius was a renaissance man who spent time as a professor at the University of Jena teaching history and poetry. After which he became a physician at the Gymnasium in Rothenburg and later founded the Gymnasium at Coburg. Libavius was most known for practicing alchemy and writing a book called Alchemia, one of the first chemistry textbooks ever written.

الحياة

Libavius was born in Halle, Germany, as Andreas Libau, the son of Johann Libau. His father, only a linen worker, could not give Libavius an education because in this time period only the wealthy were able to get a higher education.[1] Showing great intelligence as a child Livavius overcame his personal status and attended the University of Whittenburg at the age of eighteen in 1578.[1] In 1579 he entered the University of Jena where he studied philosophy, history and medicine. In 1581 he obtained the academic degree of magister artium and was named a poet laureate.

He began teaching in Ilmenau in 1581 and remained there until 1586 when he moved to Coburg to teach there. In 1588 he went to study at the University of Basel and received the degree of medicinae doctor. Shortly thereafter, he became a professor of history and poetry at the University of Jena. At the same time, he also supervised the disputations in the field of medicine.

In 1591 he became physician of the city council of Rothenburg and, one year later, became the superintendent of schools. This position led to conflict with the rector of schools causing Libavius to move to Coburg in 1605. In 1606 he was offered and accepted the position of headmaster of the reestablished Casimirianum Gymnasium in Coburg. He lived in Coburg from 1607 until his death in 1616.

Little is known about his personal life, but he did have two sons, Michael, and Andreas, who followed in his father's footsteps and became a teacher and physician. He also had two daughters, Susanna, and one whose name is not known.

الخيمياء

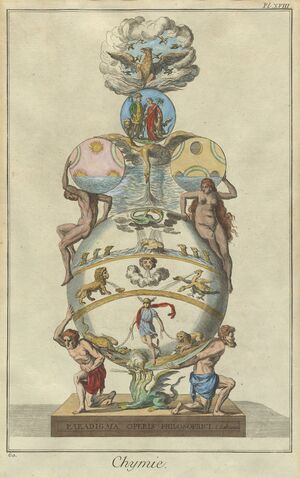

Libavius is best known for his work as an alchemist above all else. Alchemy was an early science whose goals were to transform matter like turning base metals to gold.[2] Alchemists also tried to find an elixir of life that would allow them to cure all disease.[2] Alchemy is the study that turned into what we know today as chemistry. Libavius believed that his studies in alchemy would help further advancements in the medical field.[3]

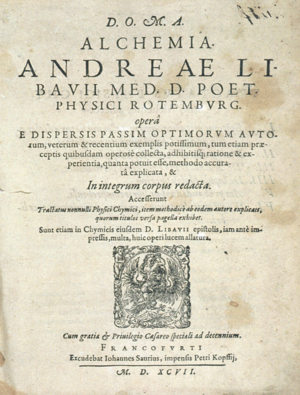

In 1597 Libavius published Alchemia, a textbook that summarized all the discoveries alchemists had made at this point. Alchemia was organized into four parts: what to have in a laboratory, descriptions of procedures, chemical analysis, and transmutation. Publishing such a book was blasphemous, as many alchemists wanted to keep their findings to themselves to prevent their findings from being misused. Libavius thought that knowledge should be shared if it could be used to help better mankind.

His studies in alchemy led to many new discoveries in chemistry. He discovered methods to prepare a number of chemicals like hydrochloric acid, ammonium sulfate and tin chloride.[2] He also recorded the dangers of alchemy, as most of it was done in homes, and proposed the development of a series of laboratories, called chemical houses, to make alchemy a safer practice.[2]

أراؤه في الخيمياء

Libavius was a staunch believer in chrysopoeia, or the ability to transmute a base metal into gold. This viewpoint was a matter of much debate for alchemists of the time, and he defended it in several of his writings. Though he did discover several new chemical processes, he tended to be more of a theoretician, and he leaned toward traditional Aristotelianism rather than Paracelsian alchemy.

He was an opponent of Paracelsus on the grounds of Paracelsus' disrespect for ancient thought, magnification of personal experience above others' experience, overstatement of the didactic function of nature, use of magical words and symbols in natural philosophy, confusion of natural and supernatural causes, interjection of seeds into the creation of the universe, and postulation of astral influences.[4] Despite this, he did not entirely reject all Paracelsian methods. In The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, Frances Yates states:

Andrea Libavius was one of those chymists who was influenced up to a point by the new teachings of Paracelsus in that he accepted the use of the new chemical remedies in medicine advocated by Paracelsus, whilst adhering theoretically to the traditional Aristotelian and Galenist teachings and rejecting Paracelsist mysticism. Aristotle and Galen appear, honourably placed, on the title-page of Libavius's main work, the Alchymia, published at Frankfurt in 1596 ... Libavius criticized the Rosicrucian Fama and Confessio in several works. Basing himself on the texts of the two manifestos, Libavius raises serious objections to them on scientific, political, and religious grounds. Libavius is strongly against theories of macro-microcosmic harmony, against Magia and Cabala, against Hermes Trismegistus (from whose supposed writings he makes many quotations), against Agrippa and Trithemius—in short he is against the Renaissance tradition.

He accepted the Paracelsian principle of using occult properties to explain phenomena with no apparent cause but rejected the conclusion that a thing possessing these properties must have an astral connection to the divine.

He was also critical of alchemists who claimed to have produced a panacea, or cure-all, not because he didn't believe that a panacea was possible, but because these alchemists invariably refused to disclose their formulas. He believed that anyone who managed to create a panacea was duty bound to teach the process to as many other people as possible, so that it could benefit mankind.[4] He was particularly critical of Georgius am Wald (also called Georgius an und von Wald), an alchemist who wrote a book in which he claimed to have made a panacea. Libavius considered am Wald to be a fraud and declared that am Wald's panacea was no more than sulfur and mercury, not gold as am Wald claimed. Between 1595 and 1596 he dedicated four volumes, Neoparacelsica, Tractatus duo physici, Gegenbericht von der Panacea Amwaldina, and Panacea Amwaldina victa to exposing am Wald as a quack.[5]

أعماله

Within a span of 25 years (1591–1616) Libavius wrote more than 40 works in the field of logic, theology, physics, medicine, chemistry, pharmacy and poetry. He was actively involved in polemics, especially in the fields of chemistry and alchemy, and as such many of his writings were controversial at the time.

Libavius was an orthodox Lutheran, and in his theological treatises, which he wrote under the pseudonym of Basilius de Varna, he criticized Catholicism, specifically the Jesuit order, and later on in his life, Calvinism. This can also be seen in some of his non-theological works, particularly in some of the works produced during his involvement with the conflict between the Paracelsists, anti-Paracelsists, Galenists, and Hermetics.[5]

In 1597, he wrote the first systematic chemistry textbook, Alchymia, where he described the possibility of transmutation. In this book he also showed that cuprous salt lotions are detectable with ammonia, which causes them to change color to dark blue. In 1615 he wrote Syntagmatis alchamiae arcanorum where he detailed the production of tin chloride, something that he developed in 1605. He was not the first person to invent this process, however, as the Franciscan friar Ulmannus had discovered it earlier and wrote about in the book Buch der heiligen Dreifaltigkeit in 1415.

He also contributed works to the study of medicine. Between 1599 and 1601 he wrote Singularia, a four volume collection of lectures on natural science, which included a collection of descriptions and discussions about medical phenomena. In 1610 he published one of the first German medical texts, Tractatus Medicus Physicus und Historia des fürtrefflichen Casimirianischen SawerBrunnen/ unter Libenstein/ nicht fern von Schmalkalden gelegen.

أعمال أخرى

- Quaestionum physicarum – 1591

- Dialectica – 1593

- Neoparacelsica – 1594

- Tractatus duo physici – 1594

- Exercitiorum logicorum liber – 1595

- Dialogus logicus – 1595

- Antigramania – 1595

- Gegenbericht von der Panacea Amwaldina, auff Georg vom Waldt davon aussgegangenen Bericht – 1595

- Singularium pars prima … pars secunda – 1595

- Tetraemerum – 1596

- Commentationum metallicorum libri – 1597

- Variarum controversarium libri duo – 1601

- Analysis dialéctica colloquii Ratisbonensis – 1602

- Poemata epica, lyrica, et elegica – 1602

- Alchymistische Practic – 1603 (Digitalisat)

- Gretserus triumphatus – 1604

- Praxis alchymiae – 1604

- Alchymia triumphans – 1607

- Pharmacopea – 1607

- Syntagma selectorum – 1611

- Syntagma arcanorum – 1613

- Syntagmatis arcanorum chymicorum – 1613

- Examen philosophiae novae – 1615

- Analysis confessionis Fraternitatis de Rosae Cruce – 1615

- Wolmeinendes Bedencken / Von der Fama, und Confession der Brüderschaft deß Rosen Creutzes – 1616

المراجع

- ^ أ ب "Andreas Libavius | German chemist and physician". Encyclopedia Britannica (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ^ أ ب ت ث "Andreas Libavius | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ^ "Andreas Libavius". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- ^ أ ب Benbow, Peter K. (2009). "Theory and Action in the Works of Andreas Libavius and Other Alchemists". Annals of Science. 66 (1): 135–139. doi:10.1080/00033790802136421. S2CID 218636935.

- ^ أ ب "Libavius (or Libau), Andreas." Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 2008. Encyclopedia.com.

- Owen Hannaway (1986). "Laboratory Design and the Aim of Science: Andreas Libavius versus Tycho Brahe". Isis. 77 (4): 584–610. doi:10.1086/354267. S2CID 144538848.

- Frances Yates, The Rosicrucian Enlightenment RKP 1972

- "AndreaasLibavius (or Libau), Andreas." Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 2008. Encyclopedia.com.

- Benbow, Peter K. 2009. "Theory and Action in the Works of Andreas Libavius and Other Alchemists." Annals of Science 66, no. 1: 135-139.

للاستزادة

- Rice University article

- Indiana University article**

- Forshaw, Peter J (2008) "Paradoxes, Absurdities, and Madness": Conflict over Alchemy, Magic and Medicine in the Works of Andreas Libavius and Heinrich Khunrath.

- Dr. Günther Bugge: Das Buch der Grossen Chemiker; first volume from Zosimos to Schönbein, publisher Chemie, GMBH Weinheim/ Bergstr. final pressing 1955, p. 107-124

- Complete History of Scientific Biography

- Friedemann Rex: Libavius, Andreas. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Bd. 14, Berlin قالب:NDB/Jahr, S. 441–442.

وصلات خارجية

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries[dead link] High resolution images of works by and/or portraits of Andreas Libavius in .jpg and .tiff format.

- Andreas Libavius (1606) Alchymia - digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library.

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with dead external links from June 2020

- مواليد عقد 1550

- 1616 deaths

- 16th-century alchemists

- 16th-century German physicians

- 16th-century German writers

- 16th-century German male writers

- 17th-century alchemists

- 17th-century German physicians

- 17th-century German writers

- 17th-century German male writers

- German alchemists

- 17th-century German chemists

- People from Halle (Saale)

- Academic staff of the University of Jena