أرمينيا البقردونية

مملكة أرمنيا البقردية Bagratid Kingdom of Armenia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 880–1045 | |||||||||||||||

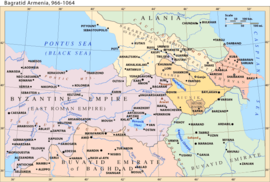

أرمنيا البقردونية، حوالي 1000 | |||||||||||||||

| المكانة | مملكة | ||||||||||||||

| العاصمة | Bagaran (885–890) Shirakavan (890–929) Kars (929–961)[1] Ani (961–1045) | ||||||||||||||

| اللغات الشائعة | الأرمنية | ||||||||||||||

| الدين | الرسولية الأرمنية | ||||||||||||||

| الحكومة | ملكية | ||||||||||||||

| أسرة بقردوني | |||||||||||||||

• 885–890 | أشوت الأول من أرمنيا | ||||||||||||||

• 890–914 | Smbat I | ||||||||||||||

• 914–928 | أشوت الثاني | ||||||||||||||

• 928–953 | Abas I | ||||||||||||||

• 953–977 | Ashot III | ||||||||||||||

• 977–989 | Smbat II | ||||||||||||||

• 989–1020 | Gagik I | ||||||||||||||

• 1020–1040 (1021–1039) | Hovhannes-Smbat III Ashot IV (بنفس الوقت) | ||||||||||||||

• 1042–1045 | Gagik II | ||||||||||||||

| الحقبة التاريخية | العصور الوسطى | ||||||||||||||

• تأسست | 880 | ||||||||||||||

• انحلت | 1045 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 1000 | 140,000 km2 (54,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Hyperpyron الدينار العباسي | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

جزء من سلسلة عن |

|---|

| تاريخ أرمينيا |

مملكة أرمنيا البقردونية Bagratid Kingdom of Armenia، كما تُعرف بإسم أرمنيا البقردونية (بالأرمينية: Բագրատունյաց Հայաստան Bagratunyats Hayastan أو Բագրատունիների թագավորություն, Bagratunineri t’agavorut’yun، "مملكة البقردوني"؛ إنگليزية: Bagratid Armenia؛ )، كانت دولة مستقلة أسسها أشوت الأول بقردوني في مطلع ع880[2] following nearly two centuries of foreign domination of Greater Armenia under Arab Umayyad and Abbasid rule. With the two contemporary powers in the region, the Abbasids and Byzantines, too preoccupied to concentrate their forces in subjugating the people of the region and the dissipation of several of the Armenian nakharar noble families, Ashot was able to assert himself as the leading figure of a movement to dislodge the Arabs from Armenia.[3]

Ashot's prestige rose as he was courted by both Byzantine and Arab leaders eager to maintain a buffer state near their frontiers. The Caliphate recognized Ashot as "prince of princes" in 862 and, later on, king in 884 or 885. The establishment of the Bagratuni kingdom later led to the founding of several other Armenian principalities and kingdoms: Taron, Vaspurakan, Kars, Khachen and Syunik.[4] Unity among all these states was sometimes difficult to maintain while the Byzantines and Arabs lost no time in exploiting the kingdom's situation to their own gains.[بحاجة لمصدر] Under the reign of Ashot III, Ani became the kingdom's capital and grew into a thriving economic and cultural center.[5]

The first half of the 11th century saw the decline and eventual collapse of the kingdom. With emperor Basil II's string of victories in annexing parts of southwestern Armenia, King Hovhannes-Smbat felt forced to cede his lands and in 1022 promised to "will" his kingdom to the Byzantines following his death. However, after Hovhannes-Smbat's death in 1041, his successor, Gagik II, refused to hand over Ani and continued resistance until 1045, when his kingdom, plagued with internal and external threats, was finally taken by Byzantine forces.[6]

التاريخ

خلفية

The weakening of the Sassanian Empire during the 7th century led to the rise of another regional power, the Muslim Arabs. The Umayyad Arabs had conquered vast swaths of territory in the Middle East and, turning north, began to periodically launch raids into Armenia territory in 640. Theodore Rshtuni, the Armenian Curopalates, signed a peace treaty with the Caliphate although the continuing war with the Arabs and Byzantines soon lead to further destruction throughout Armenia. In 661, Armenian leaders agreed to submit under Muslim rule while the latter conceded to recognize Grigor Mamikonian from the powerful Mamikonian nakharar family as ishkhan (or prince) of Armenia.[7] Known as "al-Arminiya" with its capital at Dvin, the province was headed by an ostikan, or governor.

However, Umayyad rule in Armenia grew in cruelty in the early 8th century. Revolts against the Arabs spread throughout Armenia until 705, when under the pretext of meeting for negotiations, the Arab ostikan of Nakhichevan massacred almost all of the Armenian nobility.[8] The Arabs attempted to conciliate with the Armenians but the levying of higher taxes, impoverishment of the country due to a lack of regional trade, and the Umayyads' preference of the Bagratuni family over the Mamikonians (other notable families included the Artsruni, Kamsarakan, and Rshtuni) made this difficult to accomplish. Taking advantage of the overthrow of the Umayyads by the 'Abbasids, a second rebellion was conceived although it too was met with failure partly because of the frictional relationship between the Bagratuni and Mamikonian families. The rebellion's failure also resulted in the near disintegration of the Mamikonian house which lost most of the land it controlled (members of the Artstruni house were able to escape and settle in Vaspurakan).

A third and final rebellion, stemming from similar grievances as the second, was launched in 774 under the leadership of Mushegh Mamikonian and with the support of other nakharars. The Abbasid Arabs, however, marched into Armenia with an army of 30,000 men and decisively crushed the rebellion and its instigators at the battle of Bagrevand on April 24, 775, leaving a void for the sole largely intact family, the Bagratunis, to fill.[9]

Rise of the Bagratids

The Bagratuni family had done its best to improve its relations with the Abbasid caliphs ever since they took power in 750. The Abbasids always treated the family's overtures with suspicion but by the early 770s, the Bagratunis had won them over and the relationship between the two drastically improved: the Bagratuni family members were soon viewed as leaders of the Armenians in the region.[10] Following the end of the third rebellion, which the Bagratunis had wisely chosen not to participate in, and the dispersal of several of the princely houses, the family was left without any formidable rivals. Nevertheless, any immediate opportunities to take full control of the region was complicated by Arab immigration to Armenia and the caliph's appointment of emirs to rule in newly created administrative districts (emirates). Fortunately for the Armenians, the number of Arabs residing in Armenia never grew in number to form a majority nor were the emirates fully subordinate to the Caliph.[11] As historian George Bournoutian observes, "this fragmentation of Arab authority provided the opportunity for the resurgence" of the Bagratuni family headed by Ashot Msaker (the "Meat-Eater").[12]

Establishment of the kingdom

Smbat I

As Yusuf began a new campaign against Smbat in conjunction with Gagik in 909, neither the Byzantines nor the Caliph sent aid to Smbat; several Armenian princes also chose to withhold their support. Those who did ally with Smbat were dealt brutally by Yusuf's powerful army: Smbat's son Mushegh, his nephew Smbat Bagratuni, and Grigor II of Western Syunik were all poisoned.[13] Yusuf's army ravaged the rest of Armenia as it advanced towards Blue Fortress, where Smbat had taken refuge, and besieged it for some time. Smbat finally decided to surrender himself to Yusuf in 914 in hopes of ending the Arab onslaught; Yusuf, however, showed no compassion towards his prisoner as he tortured the Armenian king to death and put his headless body on display on a cross in Dvin.[14]

Resurgence under Ashot Yerkat

Yusuf's invasion of Armenia had left the kingdom in ruins and this fact resonated among the Armenian princes who were left aghast in witnessing the Arab ostikan's brutality. Gagik I was especially shaken and he soon disavowed his loyalty to Yusuf and began to campaign against him. With Yusuf distracted by the resistance put up by his former ally, Smbat's son Ashot II felt it appropriate to assume his father's throne.

Stability under Abas

Abas I's reign was characterized with an unusual period of stability and prosperity that Armenia had not enjoyed for decades.[15] His capital was based at the fortress-city of Kars and Abas achieved numerous successes on both the foreign and domestic fronts. In the same year that he became king, Abas traveled to Dvin, where he was able to convince the Arab governor there to release several Armenian hostages and turn over control of the pontifical palace back to Armenia. Conflict between the Arabs were minimal too, with the exception of a military defeat Abas suffered near the city of Vagharshapat. He was far less conciliatory towards the Byzantines, who had repeatedly demonstrated their unreliability as allies by attacking and annexing Armenian territories. Fortunately for him, Romanus of Byzantium was more focused on fighting the Arab Hamdanids, leaving Abas virtually free to conduct his policies without foreign hindrance.[16]

Armenia's Golden Age

Ashot III's official investiture as king of Armenia took place in 961, following the relocation of the Holy See from Vaspurakan to Argina, near the city of Ani. In attendance were several contingents of the Armenian military, 40 bishops, the king of Caucasian Albania, as well as Catholicos Anania Mokatsi who crowned the king with the title of shahanshah.[17] In that same year, Ashot had also relocated the capital from Kars to Ani. The Bagratuni kings had never chosen a city to settle in, alternating from Bagaran to Shirakavan to Kars; Kars never did reach a status where it could become a capital and Dvin was disregarded altogether, given its proximity to the hostile emirates. Ani's natural defenses were well suited Ashot's desire to secure an area which could withstand siege and fell on a trade route that passed from Dvin to Trebizond.[18]

Decline and Byzantine encroachment

The Byzantines had slowly been creeping eastward towards Armenia in the final decade of the 10th century. Emperor Basil II's numerous victories against the Arabs and internal Arab struggles helped clear a path towards the Caucasus. Constantinople's official policy was that no Christian ruler is equal to or independent of the Byzantine emperor, and even if it was at time masked with diplomatic compromises, the empire's ultimate goal was the complete annexation of the Armenian realms.[19] By the middle of the 10th century, the Byzantine Empire lay along the full length of the western border of Armenia. Taron was the first Armenian region annexed by the Byzantine Empire. In a certain sense, the Byzantines considered the Bagratuni princes of Taron as their vassals, for they had consistently accepted titles, such as that of strategos, and stipends from Constantinople. With the death of Ashot Bagratuni of Taron in 967 (not to be confused with Ashot III), his sons Gregory and Bagrat were not able to withstand the pressure from the empire, which annexed their principality outright and converted it to a theme.[19]

Internal Quarrels and Fall

Culture and society

Government

The king of Bagratuni Armenia held unlimited powers and was the ultimate authority when it came to resolving questions on foreign and domestic affairs. The princes and nakharars were directly subordinate to the king and received and kept their lands only through his permission. Should certain nobles have disobeyed the king's orders, he would have the right to confiscate their lands and distribute them to other nobles.[4] The concept of divine right, however, did not exist and insubordination by the nakharar elite could only be matched by the steadfastness of the king himself.

Religion

Economy

The Bagratuni kingdom was based on essentially two economies: one which was centered around agriculture based on feudalism and the other which was concentrated on mercantilism in towns and cities. Peasants (known as ramiks) formed the lowest class in the economic stratum and largely busied themselves with raising livestock and farming. Many of them did not own land, and lived as tenants and worked as hired hands or even slaves on the lands owned by wealthy feudal magnates. Peasants were forced to pay heavy taxes to the government and the Armenian Apostolic Church in addition to their feudal lords.[4] Most peasants remained poor and the massive tax burden they shouldered sometimes culminated in peasant uprisings which the state was forced to put down.[20]

الديمغرافيا

During the Bagratuni period, the great majority of the population of Armenia remained Armenian. 10th-century Arab sources attest that the cities of the Araxes valley remained predominantly Armenian and Christian despite Arab Muslim rule. In fact, the 10th-century Arab geographer Ibn Hawqal specified that Armenian was used in Dvin and Nakhichevan.[21] Regardless, there was a notable Muslim presence in certain regions of Armenia. For instance, the southern region of Aghdznik was heavily Arabized since earlier periods of Muslim dominance. On the north shore of Lake Van in the ninth and tenth centuries, there was also a considerable Muslim population that consisted of ethnic Arabs, and later Dailamites from Azerbaijan.[21]

Art and literature

The Arab raids and invasion of Armenia as well as the devastation wrought upon the land during the Byzantine-Arab wars had largely stifled any expression of Armenian culture in fields such as historiography, literature and architecture. These restrictions disappeared when the Bagratuni kingdom was established, ushering in a new golden age of Armenian culture.

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 371. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Grigoryan, M. (2012). "Բագրատունյաց թագավորության սկզբնավորման թվագրության շուրջ [On Dating Bagratid Armenia]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in الأرمنية) (2–3): 114–125.

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. (2006). A Concise History of the Armenian People: From Ancient Times to the Present. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-56859-141-4.

- ^ أ ب ت (أرمنية) Ter-Ghevondyan, Aram N. «Բագրատունիների Թագավորություն» (Bagratuni Kingdom). Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia. vol. ii. Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1976, p. 202.

- ^ Ghafadaryan, Karo (1974). "Անի [Ani]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia (in الأرمنية). Vol. 1. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences. pp. 407–412.

- ^ Bournoutian. Concise History, p. 87.

- ^ Ter-Ghevondyan, Aram N. Արաբական Ամիրայությունները Բագրատունյաց Հայաստանում (The Arab Emirates in Bagratuni Armenia) (in الأرمنية). Yerevan, Armenian SSRyear = 1965: Armenian Academy of Sciences. pp. 42–43.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Ter-Ghevondyan. Arab Emirates, p. 44.

- ^ Ter-Ghevondyan. Arab Emirates, p. 45.

- ^ Bournoutian. Concise History, p. 74.

- ^ Bournoutian. Concise History, pp. 74-75.

- ^ Bournoutian. Concise History, p. 75.

- ^ Garsoian. "Independent Kingdoms", p. 157.

- ^ Garsoian. "Independent Kingdoms", pp. 157–158.

- ^ Chamchyants, Mikhail (2005). History of Armenia from B.C. 2247 to the Year of Christ 1780, or 1229 of the Armenian Era: Volume 2. Boston: Adamant Media Corporation. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-1-4021-4853-8.

- ^ Runciman. Romanus Lecapenus, pp. 156–157.

- ^ (أرمنية) Arakelyan, Babken N. "Բագրատունյաց թագավորության բարգավաճումը" ("The Flourishing of the Bagratuni Kingdom"). History of the Armenian People. vol. iii. Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1976, p. 53.

- ^ Arakelyan. "Bagratuni Kingdom", pp. 52-58.

- ^ أ ب Hovannisian, Richard G. (2004). The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 187–193. ISBN 1-4039-6421-1.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H (2000). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-226-33228-4.

- ^ أ ب Hovannisian. The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume I, pp. 176–177.

للاستزادة

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.) The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times, Volume I, The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1997. ISBN 978-0-312-10169-5.

- Grousset, René. Histoire de l'Arménie: des origines à 1071. Paris: Payot, 1947. (بالفرنسية)

- Ter-Ghevondyan, Aram N. Արաբական Ամիրայությունները Բագրատունյաց Հայաստանում (The Arab Emirates in Bagratuni Armenia). Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1965. (أرمنية)

- Toumanoff, Cyril. "Armenia and Georgia." Cambridge Medieval History. vol. vi: part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966.

- Yuzbashyan, Karen. N. Армянские государства эпохи Багратидов и Византия, IX-XI вв (The Armenian State in the Bagratuni and Byzantine Period, 9th-11th centuries). Moscow, 1988. (بالروسية)

وصلات خارجية

- Armenian History; Tacentral.com

- VirtualANI: Dedicated to the Deserted Medieval Armenian City of Ani On the architecture of Ani as well as general Armenian architecture.

- The Arts of Armenia by Dickran Kouymjian. Armenian Studies Program at California State University, Fresno.

- Notable societies of Europe, 900 A.D.

- CS1 الأرمنية-language sources (hy)

- CS1 maint: location

- Pages using infobox country with unknown parameters

- Articles containing أرمنية-language text

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2010

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Bagratid Armenia