ليزر Nd:YAG

Nd:YAG (مغموساً في النيوديميوم: إيتريوم ألومنيوم گارنت neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet؛ Nd:Y3Al5O12) هي بلورة تستخدم كوسط باقي لليزرات الحالة الصلبة. الغموس، النيوديميوم المؤين ثلاث مرات، Nd(III)، يحل نمطياً محل نسبة ضئيلة (1%) من أيونات الإيتريوم في البنية البلورية المضيفة من إيتريوم ألومنيوم گارنت (YAG)، وذلك لأن الأيونين لهما نفس الحجم.[1] وأيون النيوديميوم هو الذي يمنح النشاط الليزري في البلورة، بنفس الطريقة التي يقوم بها الكروم الأحمر في ليزر الياقوت.[1]

عمل الليزر في Nd:YAG عرضه لأول مرة J. E. Geusic et al. في معامل بل في 1964.[2]

التكنولوجيا

Nd:YAG lasers are optically pumped using a flashtube or laser diodes. These are one of the most common types of laser, and are used for many different applications. Nd:YAG lasers typically emit light with a wavelength of 1064 nm, in the infrared.[3] However, there are also transitions near 940, 1120, 1320, and 1440 nm. Nd:YAG lasers operate in both pulsed and continuous mode. Pulsed Nd:YAG lasers are typically operated in the so-called Q-switching mode: An optical switch is inserted in the laser cavity waiting for a maximum population inversion in the neodymium ions before it opens. Then the light wave can run through the cavity, depopulating the excited laser medium at maximum population inversion. In this Q-switched mode, output powers of 250 megawatts and pulse durations of 10 to 25 nanoseconds have been achieved.[4] The high-intensity pulses may be efficiently frequency doubled to generate laser light at 532 nm, or higher harmonics at 355, 266 and 213 nm.

Nd:YAG absorbs mostly in the bands between 730–760 nm and 790–820 nm.[3] At low current densities krypton flashlamps have higher output in those bands than do the more common xenon lamps, which produce more light at around 900 nm. The former are therefore more efficient for pumping Nd:YAG lasers.[5]

The amount of the neodymium dopant in the material varies according to its use. For continuous wave output, the doping is significantly lower than for pulsed lasers. The lightly doped CW rods can be optically distinguished by being less colored, almost white, while higher-doped rods are pink-purplish.

Other common host materials for neodymium are: YLF (yttrium lithium fluoride, 1047 and 1053 nm), YVO4 (yttrium orthovanadate, 1064 nm), and glass. A particular host material is chosen in order to obtain a desired combination of optical, mechanical, and thermal properties. Nd:YAG lasers and variants are pumped either by flashtubes, continuous gas discharge lamps, or near-infrared laser diodes (DPSS lasers). Prestabilized laser (PSL) types of Nd:YAG lasers have proved to be particularly useful in providing the main beams for gravitational wave interferometers such as LIGO, VIRGO, GEO600 and TAMA.

التطبيقات

الطب

التصنيع

ديناميكا الموائع

طب الأسنان

Nd:YAG dental lasers are used for soft tissue surgeries in the oral cavity, such as gingivectomy, periodontal sulcular debridement, LANAP, frenectomy, biopsy, and coagulation of graft donor sites.

التطبيقات العسكرية

The Nd:YAG laser is the most common laser used in laser designators and laser rangefinders.

The Chinese ZM-87 blinding laser weapon uses a laser of this type, though only 22 have been produced due to their prohibition by the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons.

التاريخ

ألايد سيگنال: ليزرات الحالة الصلبة عالية ومتوسطة القوة

In 1987 we continued a broad-based, aggressive R&D program aimed at developing the technologies necessary to make possible the use of solid state lasers that are capable of delivering medium- to high-average power in new and demanding applications. Our efforts were focused along the following major lines: development of laser and nonlinear optical materials, and of coatings for parasitic suppression and evanescent wave control; development of computational design tools; verification of computational models on thoroughly instrumented test beds; and application of selected aspects of this technology to specific missions.[6]

In the laser materials area, our efforts were directed towards producing strong, low-loss laser glasses and large, high-quality garnet crystals. We worked with the major laser glass companies (Schott and Hoya) to develop compositions tailored for high-average-power operation. This work produced high optical quality glasses that are free of platinum inclusions and whose absorption loss is about 3 x 10"3 cm"l in large castings and an order of magnitude lower in smaller castings. We have reduced to practice surface finishing and surface ion exchange techniques that increase the surface tensile strengths of these materials by factors of 5 to 10.

Our crystal program consisted of computational and experimental efforts aimed at understanding the physics, thermodynamics, and chemistry of large garnet crystal growth, and of experimental programs at Allied Signal Corp. dedicated to the growth of Nd:YAG and Nd:GSGG. These efforts have improved our understanding of the Czochralski crystal growth process and of its limits. Significant progress was made in growing flatinterface Nd:YAG, but cracking of large boules remains a problem. A number of large boules of Nd:GSGG were grown, and we are now concentrating on reducing the absorption loss in these crystals. A significant outgrowth of this research is the development of the moving melt zone technique for large crystal growth. This research effort, now supported in part by funds from the Laboratory's Institutional Research and Development Program, is proceeding rapidly.

Our laser experimental efforts were directed at understanding thermally induced wave front aberrations in zig-zag slabs, understanding fluid mechanics, heat transfer, and optical interactions in gas-cooled slabs, and conducting critical test-bed experiments with various electrooptic switch geometries. We now have a clear understanding of most of the physics and engineering issues involved and will integrate many of these components into an operating laser in 1988.

أحد استخدامات ليزر الحالة الصلبة هو لاتصالات الغواصات. The approach described in this section is that of designing and testing a semiconductor laser-pumped solid state laser that is conveniently frequency doubled to للحصول بكفاءة على طول موجة الليزر المطلوب. Development tasks include spectroscopic studies of a variety of rare earth ion-doped crystal and glass hosts, development of suitable semiconductor diode array pump sources, laser characterization studies, and modeling satellite system cost sensitivities as determined by laser transmitter performance for a variety of space-based applications.

الخصائص الطبيعية والكيميائية للـ Nd:YAG

خصائص بلورة YAG

- Formula: Y3Al5O12

- Molecular weight: 596.7

- Crystal structure: Cubic

- Hardness: 8–8.5 (Moh)

- Melting point: 1950 °C (3540 °F)

- Density: 4.55 g/cm3

Refractive index of Nd:YAG

| طول الموجة (μm) | Index n (25 °C) |

|---|---|

| 0.8 | 1.8245 |

| 0.9 | 1.8222 |

| 1.0 | 1.8197 |

| 1.2 | 1.8152 |

| 1.4 | 1.8121 |

| 1.5 | 1.8121 |

خصائص Nd:YAG @ 25 °س (بغمس 1% Nd )

- Formula: Y2.97Nd0.03Al5O12

- Weight of Nd: 0.725%

- Atoms of Nd per unit volume: 1.38×1020 /cm3

- Charge state of Nd: 3+

- Emission wavelength: 1064 nm

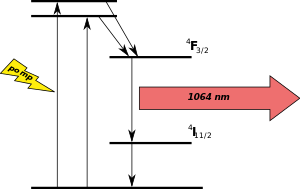

- Transition: 4F3/2 → 4I11/2

- Duration of fluorescence: 230 μs

- Thermal conductivity: 0.14 W·cm−1·K−1

- Specific heat capacity: 0.59 J·g−1·K−1

- التمدد الحراري: 6.9×10−6 K−1

- dn/dT: 7.3×10−6 K−1

- Young's modulus: 3.17×104 K·g/mm−2

- Poisson's ratio: 0.25

- Resistance to thermal shock: 790 W·m−1

الهامش والملاحظات

- ^ أ ب Koechner §2.3, pp. 48–53.

- ^ Geusic, J. E.; Marcos, H. M.; Van Uitert, L. G. (1964). "Laser oscillations in nd-doped yttrium aluminum, yttrium gallium and gadolinium garnets". Applied Physics Letters. 4 (10): 182. Bibcode:1964ApPhL...4..182G. doi:10.1063/1.1753928.

- ^ أ ب Yariv, Amnon (1989). Quantum Electronics (3rd ed.). Wiley. pp. 208–211. ISBN 0-471-60997-8.

- ^ Walter Koechner (1965) Solid-state laser engineering, Springer-Verlag, p. 507

- ^ Koechner §6.1.1, pp. 251–264.

- ^ J. Z. Hoitz (1987). "Laser Program Annual Report".

- Siegman, Anthony E. (1986). Lasers. University Science Books. ISBN 0-935702-11-3.

- Koechner, Walter (1988). Solid-State Laser Engineering (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-18747-2.