كهوف باتو

| كهوف باتو | |

|---|---|

Entrance to Batu Caves and the Murugan statue | |

| الدين | |

| الارتباط | الهندوسية |

| المقاطعة | گومباك |

| الإله | موروگان |

| الموقع | |

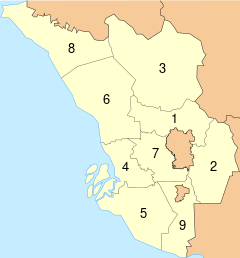

| الولاية | سلاڠور |

| البلد | ماليزيا |

Location in the Klang Valley Location in Peninsular Malaysia | |

| الإحداثيات الجغرافية | 3°14′14.64″N 101°41′2.06″E / 3.2374000°N 101.6839056°E |

| العمارة | |

| النوع المعماري | Dravidian Architecture |

| اكتمل | 1920 |

كهوف باتو ( Batu Caves ؛ بالتاميل: பத்து மலை) is a mogote (a type of karst landform) that has a series of caves and cave temples in Gombak, Selangor, Malaysia. It takes its name from the Malay word batu, meaning 'rock'.[1][2] The cave complex is one of the most popular Hindu shrines outside India, and is dedicated to Murugan. It is the focal point of the Tamil festival of Thaipusam in Malaysia.

The hill was originally known as Kapal Tanggang (the Ship of Si Tanggang) from the folktale Malin Kundang.[3] The Tamil name means "10th Hill" as there are six important Murugan shrines in India and four more in Malaysia. The three others in Malaysia are Kallumalai Temple in Ipoh, Tanneermalai Temple in Penang and Sannasimalai Temple in Malacca.

التاريخ

The limestone forming Batu Caves is said to be around 400 million years old. Some of the cave entrances were used as shelters by the indigenous Temuan people (a tribe of Orang Asli).

As early as 1860, Chinese settlers began excavating guano for fertilising their vegetable patches. However, they became famous only after the limestone hills were recorded by colonial authorities including Daly and Syers as well as American Naturalist, William Hornaday in 1878.

Batu Caves was promoted as a place of worship by K. Thamboosamy Pillai, an Indian Tamil trader. He was inspired by the vel-shaped entrance of the main cave and was inspired to dedicate a temple to Murugan within the caves. In 1890, Pillai, who also founded the Sri Mahamariamman Temple, Kuala Lumpur, installed the murti (consecrated statue) of Sri Murugan Swami in what is today known as the Temple Cave. Since 1892, the Thaipusam festival in the Tamil month of Thai (which falls in late January/early February) has been celebrated there.

Wooden steps up to the Temple Cave were built in 1920. In the 1930s, the stairs began to show signs of wear and tear, and then temple chairman Ramachandran Naidu proposed to build two flights of concrete stairs to the upper caves. The proposal was forwarded to Sorobgom in 1939. The work was completed in 1940, just in time for the Thaipusam celebration that year according to current temple chairman R. Nadarajah.[4] Currently there are 272 concrete steps. Of the various cave temples that comprise the site, the largest and best known is the Temple Cave, so named because it houses several Hindu shrines beneath its high vaulted ceiling.

On 1 September 1942, a village near the Caves was the site of a Communist Party of Malaya meeting convened by Lai Teck, which included the CPM's Central Executive Committee, state party officials, and a group leaders of the MPAJA. However, Lai Teck betrayed the meeting to the Japanese, who staged a surprise raid at dawn, destroying most of the CPM and MPAJA high command.

In August 2018 the 272 steps were painted, each set of steps painted in a different range of colours. However, accusations were almost immediately made by the National Heritage Department for a breach of law requiring authorisation for renovations within 200 metres of a heritage site. The temple's management disputed their failure to receive authorisation.[5][6]

الموقع الديني

At the base of the hill are two more cave temples, Art Gallery Cave and Museum Cave, both of which are full of Hindu statues and paintings. This complex was renovated and opened as the Cave Villa in 2008. Many of the shrines relate the story of Murugan's victory over the demon Surapadman. An audio tour is available to visitors.

The Ramayana Cave is situated to the extreme left as one faces the sheer wall of the hill. On the way to the Ramayana Cave, there is a 15 m (50 ft) tall statue of Hanuman and a temple dedicated to Hanuman, devotee and aide of Rama. The consecration ceremony of the temple was held in November 2001.

The Ramayana Cave depicts the story of Rama in the manner of a chronicle along the irregular walls of the cave.

A 43-metre (140 ft) high statue of Murugan was unveiled in January 2006, having taken three years to construct. It is the second-tallest Murugan statue in the world.

الإدارة

Batu Malai Sri Murugan Temple is managed by the Board of Management of Sri Maha Mariamman Temple Devasthanam, which also manages the Sri Mahamariamman Temple, Kuala Lumpur and the Kortumalai Pillaiyar Temple. It also performs the role of Hindu Religious Consultant to the Government of Malaysia in determining the Hindu yearly calendar.

Nature, flora and fauna

The Batu Cave hill and its numerous caverns contain a wealth of plants and animals, many of which are specialised for limestone environments. A total of 269 species of vascular plants have been recorded from the site, including 56 species (21%) which are obligate calciphiles (found only on limestone).[7]

There are various undeveloped caves which contain a diverse range of cave fauna, including some unique species, such as trapdoor spiders (Liphistius batuensis).[8] The caves have some 21 species of bats, including several species of fruit bats (Eonycteris).[2] The site is also well known for its numerous long-tailed macaques, which visitors feed — sometimes involuntarily. These monkeys may also pose a biting hazard to tourists (especially small children) as they can be quite territorial.

Below the Temple Cave is the Dark Cave, with speleothems and a number of animals found nowhere else. It is a two-kilometer network of relatively untouched caverns. Stalactites jutting from the cave's ceiling and stalagmites rising from the floor form intricate formations such as cave curtains, flowstones, cave pearls and scallops which took thousands of years to form.

To maintain the cave's ecology, access is restricted. The Malaysian Nature Society organises regular educational and adventure trips to the Dark Wet Caves.

Rock climbing

Batu Caves is also the centre of rock climbing development in Malaysia for the past 10 years. Batu Caves offers more than 160 climbing routes. The routes are scattered all around the side of Batu Caves, which is made up of limestone hills rising to 150 متر (490 ft). These climbing routes are easily accessed, as most crags start from ground level. These climbing routes often start from the North Eastern side of the cave complex whereas the staircase and temple entrance faces South. This Northeastern area is known as the Damai caves. Abseiling and spelunking trips can be organised with some local adventure companies.

Thaipusam festival

The Batu Caves serve as the focus of the Tamil community's yearly Thaipusam (بالتاميل: தைபூசம்) festival. They have become a pilgrimage site not only for Malaysian Hindus, but Hindus worldwide.

A procession begins in the wee hours of the morning on Thaipusam from the Sri Mahamariamman Temple, Kuala Lumpur leading up to Batu Caves as a religious undertaking to Murugan lasting eight hours. Devotees carry containers containing milk as offering to Murugan either by hand or in huge decorated carriers on their shoulders called 'Kavadi'.

The kavadi may be simple wooden arched semi-circular supports holding a carrier foisted with brass or clay pots of milk or huge, heavy ones which may rise up to two metres, built of bowed metal frames which hold long skewers, the sharpened end of which pierce the skin of the bearers torso. The kavadi is decorated with flowers and peacock feathers imported from India. Some kavadi may weigh as much as a hundred kilograms.

After bathing in the nearby Sungai Batu (Rocky River), the devotees make their way to the Temple Cave and climb the flights of stairs to the temple in the cave. Devotees use the wider centre staircase while worshippers and onlookers throng up and down those balustrades on either side.

When the kavadi bearer arrives at the foot of the 272-step stairway leading up to the Temple Cave, the devotee has to make the arduous climb.

Priests attend to the kavadi bearers. Consecrated ash is sprinkled over the hooks and skewers piercing the devotees' flesh before they are removed. No blood is shed during the piercing and removal.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Development

Housing development began around 1970 with housing estates such as Taman Batu Caves, Taman Selayang, Taman Amaniah, Taman Sri Selayang, Taman Medan Batu Caves, and Taman Gombak Permai.

In the last decade, the surrounding area has changed from a small village to industrial estates, new housing, and retail. There is also an elevated flyover across the highway. A new 515-million-ringgit KTM Komuter rail extension from Sentul to Batu Caves began operations in July 2010, serving the rebuilt Batu Caves Komuter station.

Several non-governmental organisations have expressed concerns about over-development of Batu Caves.[9]

Transportation

Batu Caves is easily reached by commuter train at the قالب:KLRT color code Batu Caves Komuter station, costing RM 2.6 for a one-way journey from قالب:KLRT color code قالب:KLRT color code قالب:KLRT color code قالب:KLRT color code قالب:KLRT color code قالب:KLRT color code قالب:KLRT color code KL Sentral. Batu Caves may also be reached by bus 11/11d from Bangkok Bank Terminus (Near to Puduraya Terminus) or bus U6 from Titiwangsa. Batu Caves is also easily reached by travelling by car.

Gallery

Sheer cliff face of exposed limestone

Icons carried in procession during Thaipusam at Batu Caves. Also seen in the background is the 42.7 m high golden statue of Murugan.

Batu Caves Murugan Statue in Batu Caves

See also

References

- ^ Lim, Teckwyn; Yussof, Sujauddin; Ashraf, Mohd. (2010). "The Caves of Batu Caves: a Toponymic Revision". Malayan Nature Journal. 62: 335–348.

- ^ أ ب Ong, Dylan Jefri (2020). Kiew, Ruth; Zubaid Akbar Mukhtar Ahmad; Ros Fatihah Haji Muhammad; Surin Suksuwan; Nur Atiqah Abd Rahman; Lim Teck Wyn (eds.). Batu Caves: Malaysia's Majestic Limestone Icon. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Cave and Karst Conservancy. p. 44. ISBN 978-967-17966-0-3.

- ^ Teckwyn, Lim; Sujauddin, Yusof; Mohd, Ashraf (2010). "The Caves of Batu Caves: a Toponymic Revision". Malayan Nature Journal. 62: 335–348.

- ^ Tajuddin, Iskandar (2016-01-24). "'It began with prayer to Lord Muruga' | New Straits Times". NST Online (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2021-06-05.

- ^ Bavani, M. (30 August 2018). "Batu Caves temple committee steps into trouble". Star. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ "Temple gets stunning paint job (shame it might be illegal)". BBC. 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Kiew, Ruth (2014-09-12). "Checklist of vascular plants from Batu Caves, Selangor, Malaysia". Check List (in الإنجليزية). 10 (6): 1420–1429. doi:10.15560/10.6.1420. ISSN 1809-127X.

- ^ T.W. Lim and S.S. Yussof (2009). "Conservation status of Batu Caves Trapdoor Spider (Liphistius batuensis Abraham (Araneae, Mesothelae)): A preliminary survey. 61: 121–132". Malayan Nature Journal. 62 (1): 121–132.

- ^ Reporters, F. M. T. (2021-09-10). "Explain land grants within Batu Caves reserve, NGOs tell Selangor". Free Malaysia Today (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2024-03-12.

External links

Media related to كهوف باتو at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to كهوف باتو at Wikimedia Commons

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing تاميلية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2011

- People from Selangor

- Gombak District

- Hindu temples in Malaysia

- Caves of Malaysia

- Limestone caves

- Hindu pilgrimage sites in Malaysia

- Hindu cave temples of Malaysia

- Nature sites of Selangor

- Religious buildings and structures in Selangor

- Landforms of Selangor

- Climbing areas of Malaysia