كريسپر

كريسپر CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) هو موضع صبغوي يحتوي على عدة تكرارات مباشرة قصيرة تم العثور عليها في جينوم ما يقرب من 40٪ من متسلسلة البكتيريا و 90٪ من متسلسلة العتيقة.[2][3]

يوجد الكريسپر في 40% من جينومات الجراثيم المتسلسلة 90% من جينومات العتائق المتسلسلة.[4][3]

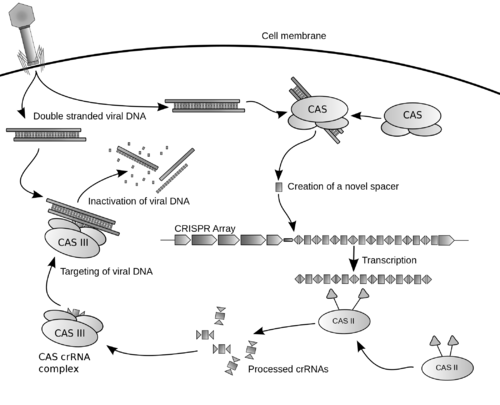

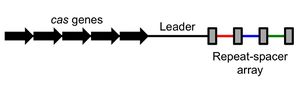

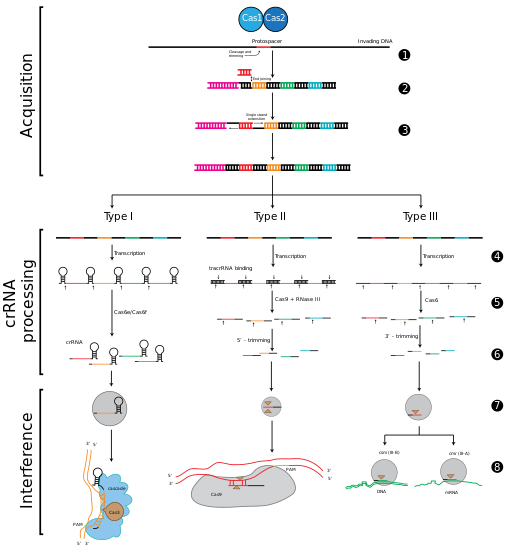

عادة ما يرتبط الكريسپر مع جينات كاس التي ترمز للپروتينات المرتبطة بالكريسپر. نظام كريسپر/كاس هو الجهاز المناعي لبدائيات النوى الذي يمنح مقاومة المواد الجينية الخارجية مثل الپلازميدات والعاثيات[5][6] ويفور شكلاً من أشكال المناعة المكتسبة. فواصل الكريسپر تتعرف وتقطع هذه المواد الجينية الغريبة بطريقة مماثلة لتداخل الحمض النووي الربيبوزي في العضيات حقيقية النوى.[7]

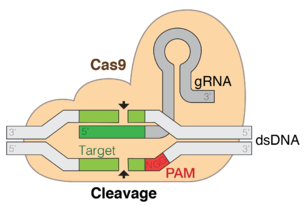

منذ 2013، يستخدم نظام كريسپر/كاس في في تحرير الجينوم (الإضافة، التعطيل، تغيير تسلسل بعض الجينات) وتنظيم الجينات في الأنواع ضمن شجرة الحياة.[8] بتقديم پروتين كاس9 والدليل المناسب للحمض النووي الربيوزي داخل الخلية، يمكن قطع جينوم العضية في المكان المطلوب.

يمكن استخدام كريسپر لبناء بواعث جينوم موجة الرنا قادرة على تغيير جينومات جميع المجموعات السكانية.[9]

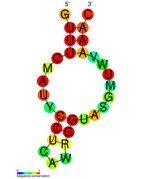

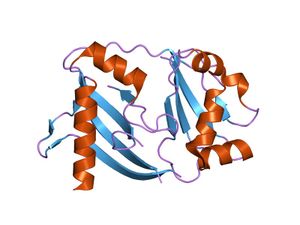

نسخة مبسطة من نظام كريسپر/كاس، كريسپر/كاس9، تم تعديلها إلى جينومات التحرير. من خلال وضع نوكلياز كاس9 المركب مع دليل الرنا (gRNA) داخل الخلية، يمكن قطع جينوم الخلية عند الموضوع المطلوب، مما يسمح بإزالة الجينات القائمة و/أو إضافة جينات جديدة.[10][11][12] يتوافق مركب كاس9-دليل الرنا مع مركب كاس 3 crRNA كما هو موضح في المخطط أعلاه.

يمكن استخدام تقنيات تحرير جينوم كريسپر/كاس في الكثير من التطبيقات، ومنها الطب وتحسين بذور الحاصلات الزراعية. استخدام مركب كريسپر/كاس9-دليل الرنا في تحرير الجينوم[13][14] كان خيار الاتحاد الأمريكي لتقدم العلوم لاختراق العام في 2015.[15] ظهر مخاوف أخلاقية حيوية حول احتمال استخدام كريسپر في تحرير الخط الجنسي.[16]

في 5 يناير 2018، أعلن العلماء عن أن كاس9 موجود ضمن أكثر من 65% من الأشخاص، مما يعني توافر الفرصة لدى هؤلاء الأشخاص للاستفادة من تطبيقات كريسپر في العلاج والوقاية من الأمراض، ولا يعني هذا أن النسبة الباقية الذين توجد لديهم أجسام مناعية تعوق عمل كريسپر لا يمكنهم الاستفادة من هذه التطبيقات، لكن التأثيرات العلاجية قد تكون أقل، وفي بعض الحالات قد تؤدي إلى ظهور آثار سمية كبيرة لدى المرضى.[17]

| كرسپر CRISPR | |

|---|---|

| |

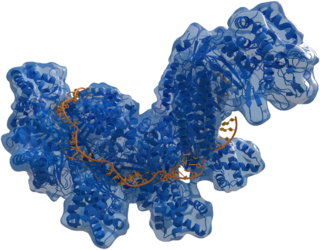

| Structure of crRNA-guided E. coli Cascade complex (Cas, blue) bound to single-stranded DNA (orange). | |

| المعرفات | |

| العضية | |

| الرمز | ? |

| بيانات أخرى | |

التاريخ

كرسپر هو جزء من عملية بكتيرية تحدث طبيعياً. فالبكتريا قد تضم دنا أجنبي وحتى قد تفترس دنا معطوب من بيئتها.[18]

التكرارات المتعقدة تم وصفهم لأول مرة في 1987 للبكتريا إشريشيا كولاي على يد الباحث في جامعة اوساكا يوشيزومي إيشينو، ولكن آنذاك فإن وظيفتهم لم تكن معروفة.[19] وقد لوحظت التكرارات، بشكل مستقل من قِبل الباحث الإسباني فرانشسكو موخيكا في 1993.[20] وسيسميهم لاحقاً "short regularly spaced repeats" (SRSR) بعد أن عثر عليهم في العديد من الميكروبات الأخرى.[21] وفي عام 2000، تم التعرف على تكرارات مشابهة في بكتريا أخرى وفي عتائق أيضاً.[21] وقد تغير اسم SRSR إلى كريسپر CRISPR في 2002 بناء على اقتراح من موخيكا.[20][22] وقد اقتـُرِح أن كريسپر هي المسئولة عن توليد المناعة المتكيفة في الميكروبات.[23] الورقة البحثية التي وصفت تلك الفكرة رُفِضت في البداية من عدد من الدوريات البارزة.[20] الأوراق البحثية التي اقترحت فرضيات مشابهة من جيل ڤرنو وبشكل مستقل، ألكسندر بولوتان واجهت رفضاً مماثلاً قبل أن تُنشر بعد لأي.[20] [24] [25]

مكتبات عشرات الآلاف من guide RNA متوفرة.[26]

أسلاف تحرير الجين

بنية المواضع

التكرار والفواصل

جينات كاس وأنواع كريسپر الفرعية

| نوع كاس | جين التوقيع | الوظيفة | المصدر |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Cas3 | Single-stranded DNA nuclease (HD domain) and ATP-dependent helicase | [27] |

| IA | Cas8a | Subunit of the interference module | [28] |

| IB | Cas8b | ||

| IC | Cas8c | ||

| ID | Cas10d | contains a domain homologous to the palm domain of nucleic acid polymerases and nucleotide cyclases | [29][30] |

| IE | Cse1 | ||

| IF | Csy1 | لم يحدد | |

| II | Cas9 | Nucleases RuvC and HNH together produce DSBs, and separately can produce single-strand breaks. Ensures the acquisition of functional spacers during adaptation. | [31][32] |

| IIA | Csn2 | لم يحدد | |

| IIB | Cas4 | لم يحدد | |

| IIC | Characterized by the absence of either Csn2 or Cas4 | [33] | |

| III | Cas10 | Homolog of Cas10d and Cse1 | [30] |

| IIIA | Csm2 | لم يحدد | |

| IIIB | Cmr5 | Not Determined |

الآلية

CRISPR-Cas immunity is a natural process of bacteria and archaea. CRISPR-Cas prevents bacteriophage infection, conjugation and natural transformation by degrading foreign nucleic acids that enter the cell.[34]

الحصول على الفواصل داخل مواضع الكريسپر

مرحلة التداخل

| الپروتين المرتبط بكريسپر | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

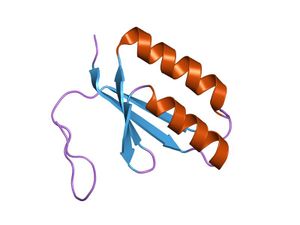

بنية الپروتين المرتبط بكريسپر. | |||||||||

| المعرفات | |||||||||

| الرمز | CRISPR_assoc | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF08798 | ||||||||

| عشيرة Pfam | CL0362 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR010179 | ||||||||

| CDD | cd09727 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| الپروتين كاس 2 المرتبط بكريسپر | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

البنية البلورية للپروتين المفترض tt1823 | |||||||||

| المعرفات | |||||||||

| الرمز | CRISPR_Cas2 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF09827 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR019199 | ||||||||

| CDD | cd09638 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| الپروتين Cse1 المرتبط بكريسپر | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| المعرفات | |||||||||

| الرمز | CRISPR_Cse1 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF09481 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR013381 | ||||||||

| CDD | cd09729 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| الپروتين Cse2 المرتبط بكريسپر | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| المعرفات | |||||||||

| الرمز | CRISPR_Cse2 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF09485 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR013382 | ||||||||

| CDD | cd09670 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

التطور والتوزيع

التطور

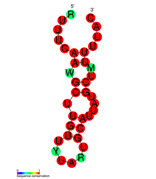

A bioinformatic study has suggested that CRISPRs are evolutionarily conserved and cluster into related types. Many show signs of a conserved secondary structure.[35]

CRISPR/Cas can immunize bacteria against certain phages and thus halt transmission. For this reason, Koonin described CRISPR/Cas as a Lamarckian inheritance mechanism.[36] However, this was disputed by a critic who noted, "We should remember [Lamarck] for the good he contributed to science, not for things that resemble his theory only superficially. Indeed, thinking of CRISPR and other phenomena as Lamarckian only obscures the simple and elegant way evolution really works".[37]

التطور المشترك

Analysis of CRISPR sequences revealed coevolution of host and viral genomes.[38] Cas9 proteins are highly enriched in pathogenic and commensal bacteria. CRISPR/Cas-mediated gene regulation may contribute to the regulation of endogenous bacterial genes, particularly during interaction with eukaryotic hosts. For example, Francisella novicida uses a unique, small, CRISPR/Cas-associated RNA (scaRNA) to repress an endogenous transcript encoding a bacterial lipoprotein that is critical for F. novicida to dampen host response and promote virulence.[39]

The basic model of CRISPR evolution is newly incorporated spacers driving phages to mutate their genomes to avoid the bacterial immune response, creating diversity in both the phage and host populations. To fight off a phage infection, the sequence of the CRISPR spacer must correspond perfectly to the sequence of the target phage gene. Phages can continue to infect their hosts given point mutations in the spacer.[40] Similar stringency is required in PAM or the bacterial strain remains phage sensitive.[41][40]

المعدلات

A study of 124 S. thermophilus strains showed that 26% of all spacers were unique and that different CRISPR loci showed different rates of spacer acquisition.[42] Some CRISPR loci evolve more rapidly than others, which allowed the strains' phylogenetic relationships to be determined. A comparative genomic analysis showed that E. coli and S. enterica evolve much more slowly than S. thermophilus. The latter's strains that diverged 250 thousand years ago still contained the same spacer complement.[43]

Metagenomic analysis of two acid mine drainage biofilms showed that one of the analyzed CRISPRs contained extensive deletions and spacer additions versus the other biofilm, suggesting a higher phage activity/prevalence in one community than the other.[44] In the oral cavity, a temporal study determined that 7-22% of spacers were shared over 17 months within an individual while less than 2% were shared across individuals.[45]

From the same environment a single strain was tracked using PCR primers specific to its CRISPR system. Broad-level results of spacer presence/absence showed significant diversity. However, this CRISPR added 3 spacers over 17 months,[45] suggesting that even in an environment with significant CRISPR diversity some loci evolve slowly.

CRISPRs were analysed from the metagenomes produced for the human microbiome project.[46] Although most were body-site specific, some within a body site are widely shared among individuals. One of these loci originated from streptococcal species and contained ~15,000 spacers, 50% of which were unique. Similar to the targeted studies of the oral cavity, some showed little evolution over time.[46]

CRISPR evolution was studied in chemostats using S. thermophilus to directly examine spacer acquisition rates. In one week, S. thermophilus strains acquired up to three spacers when challenged with a single phage.[47] During the same interval the phage developed single nucleotide polymorphisms that became fixed in the population, suggesting that targeting had prevented phage replication absent these mutations.[47]

Another S. thermophilus experiment showed that phages can infect and replicate in hosts that have only one targeting spacer. Yet another showed that sensitive hosts can exist in environments with high phage titres.[48] The chemostat and observational studies suggest many nuances to CRISPR and phage (co)evolution.

التطبيقات

By the end of 2014 some 1000 research papers had been published that mentioned CRISPR.[49][50] The technology had been used to functionally inactivate genes in human cell lines and cells, to study Candida albicans, to modify yeasts used to make biofuels and to genetically modify crop strains.[50] CRISPR can also be used to change mosquitos so they cannot transmit diseases such as malaria.[51]

CRISPR-based re-evaluations of claims for gene-disease relationships have led to the discovery of potentially important anomalies.[52]

هندسة الجينوم

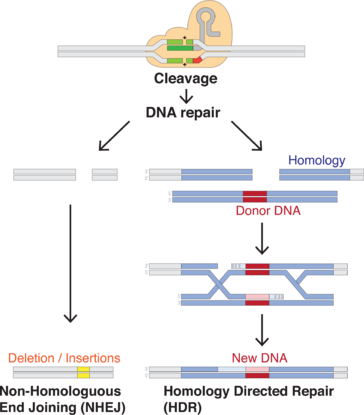

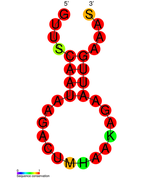

CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing is carried out with a Type II CRISPR system. When utilized for genome editing, this system includes Cas9, crRNA, tracrRNA along with an optional section of DNA repair template that is utilized in either non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology directed repair (HDR).

المكونات الرئيسية

| المكون | الوظيفة |

|---|---|

| crRNA | Contains the guide RNA that locates the correct section of host DNA along with a region that binds to tracrRNA (generally in a hairpin loop form) forming an active complex. |

| tracrRNA | Binds to crRNA and forms an active complex. |

| sgRNA | Single guide RNAs are a combined RNA consisting of a tracrRNA and at least one crRNA |

| Cas9 | Protein whose active form is able to modify DNA. Many variants exist with differing functions (i.e. single strand nicking, double strand break, DNA binding) due to Cas9's DNA site recognition function. |

| Repair template | DNA that guides the cellular repair process allowing insertion of a specific DNA sequence |

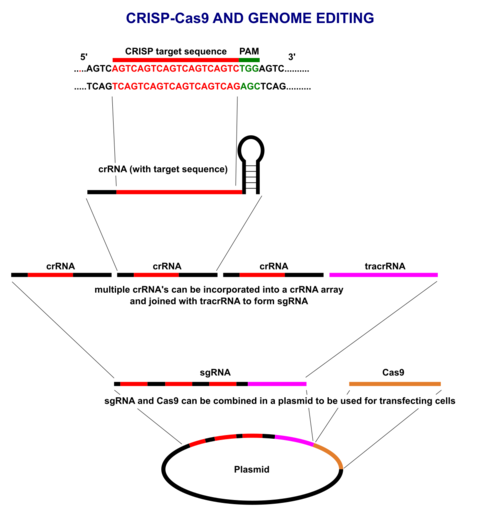

CRISPR/Cas9 often employs a plasmid to transfect the target cells.[55] The main components of this plasmid are displayed in the image and listed in the table. The crRNA needs to be designed for each application as this is the sequence that Cas9 uses to identify and directly bind to the cell's DNA. The crRNA must bind only where editing is desired. The repair template is designed for each application, as it must overlap with the sequences on either side of the cut and code for the insertion sequence.

Multiple crRNAs and the tracrRNA can be packaged together to form a single-guide RNA (sgRNA).[56] This sgRNA can be joined together with the Cas9 gene and made into a plasmid in order to be transfected into cells.

البنية

التسليم

Scientists can use viral or non-viral systems for delivery of the Cas9 and sgRNA into target cells. Electroporation of DNA, RNA or ribonucleocomplexes is the most common and cheapest system. This technique was used to edit CXCR4 and PD-1, knocking in new sequences to replace specific genetic "letters" in these proteins. The group was then able to sort the cells, using cell surface markers, to help identify successfully edited cells.[57] Deep sequencing of a target site confirmed that knock-in genome modifications had occurred with up to ∼20% efficiency, which accounted for up to approximately one-third of total editing events.[58] However, hard-to-transfect cells (stem cells, neurons, hematopoietic cells, etc.) require more efficient delivery systems such as those based on lentivirus (LVs), adenovirus (AdV) and adeno-associated virus (AAV).

التعديل

CRISPRs have been used to cut five[26] to 62 genes at once: pig cells have been engineered to inactivate all 62 Porcine Endogenous Retroviruses in the pig genome, which eliminated transinfection from the pig to human cells in culture.[59] CRISPR's low cost compared to alternatives is widely seen as revolutionary.[10][11]

Selective engineered redirection of the CRISPR/Cas system was first demonstrated in 2012 in:[60][61]

- Immunization of industrially important bacteria, including some used in food production and large-scale fermentation

- Cellular or organism RNA-guided genome engineering. Proof of concept studies demonstrated examples both in vitro[12][62][31] and in vivo[63][64][65]

- Bacterial strain discrimination by comparison of spacer sequences[بحاجة لمصدر]

التعديل المحكوم للجينوم

Several variants of CRISPR/Cas9 allow gene activation or genome editing with an external trigger such as light or small molecules.[66][67][68] These include photoactivatable CRISPR systems developed by fusing light-responsive protein partners with an activator domain and a dCas9 for gene activation,[69][70] or fusing similar light responsive domains with two constructs of split-Cas9,[71][72] or by incorporating caged unnatural amino acids into Cas9,[73] or by modifying the guide RNAs with photocleavable complements for genome editing.[74]

In 2017, researchers successfully used CRISPR-Cas9 as a treatment in a mouse model of human genetic deafness, by genetically editing the DNA in some cells in the ears of live mice.[75]

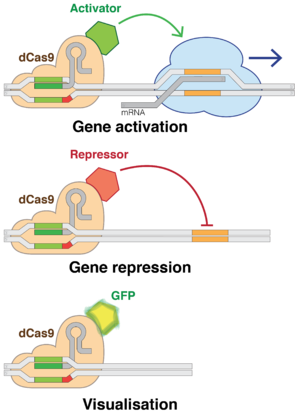

Knockdown/التفعيل

Using "dead" versions of Cas9 (dCas9) eliminates CRISPR's DNA-cutting ability, while preserving its ability to target desirable sequences. Multiple groups added various regulatory factors to dCas9s, enabling them to turn almost any gene on or off or adjust its level of activity.[76] Like RNAi, CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) turns off genes in a reversible fashion by targeting, but not cutting a site. The targeted site is methylated, epigenetically modifying the gene. This modification inhibits transcription. Conversely, CRISPR-mediated activation (CRISPRa) promotes gene transcription.[77] Cas9 is an effective way of targeting and silencing specific genes at the DNA level.[78] In bacteria, the presence of Cas9 alone is enough to block transcription. For mammalian applications, a section of protein is added. Its guide RNA targets regulatory DNA sequences called promoters that immediately precede the target gene.[26]

Cas9 was used to carry synthetic transcription factors that activated specific human genes. The technique achieved a strong effect by targeting multiple CRISPR constructs to slightly different locations on the gene's promoter.[26]

تعديل الرنا

In 2016 researchers demonstrated that CRISPR from an ordinary mouth bacterium could be used to edit RNA. The researchers searched databases containing hundreds of millions of genetic sequences for those that resembled Crispr genes. They considered the fusobacteria Leptotrichia shahii. It had a group of genes that resembled CRISPR genes, but with important differences. When the researchers equipped other bacteria with these genes, which they called C2c2, they found that the organisms gained a novel defense.[79]

Many viruses encode their genetic information in RNA rather than DNA that they repurpose to make new viruses. HIV and poliovirus are such viruses. Bacteria with C2c2 make molecules that can dismember RNA, destroying the virus. Tailoring these genes opened any RNA molecule to editing.[79]

نماذج الأمراض

الوظائف

التحرير

Reversible knockdown

التنشيط

الاستخدام حسب العاثية

براءات الاختراع والتسويق

المجتمع والثقافة

تعديل خط جنس بشري

At least four labs in the US, labs in China and the UK, and a US biotechnology company called Ovascience announced plans or ongoing research to apply CRISPR to human embryos.[80] Scientists, including a CRISPR co-inventor, urged a worldwide moratorium on applying CRISPR to the human germline, especially for clinical use. They said "scientists should avoid even attempting, in lax jurisdictions, germline genome modification for clinical application in humans" until the full implications "are discussed among scientific and governmental organizations".[81][82] These scientists support basic research on CRISPR and do not see CRISPR as developed enough for any clinical use in making heritable changes to humans.[83]

عوائق سياسية أمام الهندسة الوراثية

الاعتراف بأهميته

في 2012 و 2013، حصلت كرسپر على المركز الثاني في مسابقة مجلة ساينس لجائزة اختراق العام. وفي 2015، فازت بالجائزة.[76] أُدرِجت كرسپر كأحد عشر تكنولوجيات اختراقية في مجلة إمآيتي تكنولوجي رڤيو في 2014 and 2016.[84][85] وفي 2016، فازت جنيفر دودنا و إمانوِل شارپنتييه، مع رودلف بارانگو وفيليپ هورڤات و فنگ ژانگ بجائزة گيردنر العالمية. وفي 2017، حصلت جنيفر دودنا وإمانوِل شارپنتييه على جائزة اليابان لإختراعهم الثوري CRISPR-Cas9 في طوكيو، اليابان.

قواطع بديلة

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ أ ب PMID 20056882 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ^ 71/79 Archaea, 463/1008 Bacteria CRISPRdb, Date: 19.6.2010

- ^ أ ب ت Grissa I, Vergnaud G, Pourcel C (2007). "The CRISPRdb database and tools to display CRISPRs and to generate dictionaries of spacers and repeats". BMC Bioinformatics. 8: 172. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-8-172. PMC 1892036. PMID 17521438.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) خطأ استشهاد: وسم<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "pmid17521438" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ 71/79 Archaea, 463/1008 Bacteria CRISPRdb, Date: 19.6.2010

- ^ Barrangou, R; Fremaux, C; Deveau, H; Richards, M; Boyaval, P; Moineau, S; et al. (Mar 2007). "CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes". Science. 315 (5819): 1709–1712. doi:10.1126/science.1138140. PMID 17379808.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Marraffini, LA; Sontheimer, EJ (Dec 2008). "CRISPR interference limits horizontal gene transfer in staphylococci by targeting DNA". Science. 322 (5909): 1843–1845. doi:10.1126/science.1165771. PMC 2695655. PMID 19095942.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةpmid20125085 - ^ Mali, P; Esvelt, KM; Church, GM (Oct 2013). "Cas9 as a versatile tool for engineering biology". Nature Methods. 10 (10): 957–63. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2649. PMC 4051438. PMID 24076990.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Esvelt, KM; Smidler, AL; Catteruccia, F; Church, GM (Jul 2014). "Concerning RNA-guided gene drives for the alteration of wild populations". eLife. doi:10.7554/eLife.03401. PMID 25035423.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ أ ب Ledford, Heidi (2015). "CRISPR, the disruptor". Nature. 522 (7554): 20–4. Bibcode:2015Natur.522...20L. doi:10.1038/522020a. PMID 26040877.

- ^ أ ب Snyder, Bill (21 August 2014). "New technique accelerates genome editing process". research news @ Vanderbilt. Nashville, Tennessee: Vanderbilt University.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب Hendel A, Bak RO, Clark JT, Kennedy AB, Ryan DE, Roy S, Steinfeld I, Lunstad BD, Kaiser RJ, Wilkens AB, Bacchetta R, Tsalenko A, Dellinger D, Bruhn L, Porteus MH (September 2015). "Chemically modified guide RNAs enhance CRISPR-Cas genome editing in human primary cells". Nature Biotechnology. 33 (9): 985–9. doi:10.1038/nbt.3290. PMC 4729442. PMID 26121415.

- ^ Ledford H (March 2016). "CRISPR: gene editing is just the beginning". Nature. 531 (7593): 156–9. doi:10.1038/531156a. PMID 26961639.

- ^ Maxmen, Amy (August 2015). "The Genesis Engine". WIRED. Retrieved 2016-06-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Travis J (17 December 2015). "Breakthrough of the Year: CRISPR makes the cut". Science Magazine. American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- ^ Ledford H (June 2015). "CRISPR, the disruptor". Nature. 522 (7554): 20–4. doi:10.1038/522020a. PMID 26040877.

- ^ "Uh Oh—CRISPR Might Not Work in People". technologyreview.com. 2018-01-04. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- ^ Overballe-Petersen S, Harms K, Orlando LA, Mayar JV, Rasmussen S, Dahl TW, Rosing MT, Poole AM, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Brunak S, Inselmann S, de Vries J, Wackernagel W, Pybus OG, Nielsen R, Johnsen PJ, Nielsen KM, Willerslev E (December 2013). "Bacterial natural transformation by highly fragmented and damaged DNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (49): 19860–5. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11019860O. doi:10.1073/pnas.1315278110. PMID 24248361.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lay-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|lay-source=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help)

- ^ Ishino Y, Shinagawa H, Makino K, Amemura M, Nakata A (December 1987). "Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product". Journal of Bacteriology. 169 (12): 5429–33. PMC 213968. PMID 3316184.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Lander ES (January 2016). "The Heroes of CRISPR". Cell. 164 (1–2): 18–28. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.041. PMID 26771483.

- ^ أ ب Mojica FJ, Díez-Villaseñor C, Soria E, Juez G (April 2000). "Biological significance of a family of regularly spaced repeats in the genomes of Archaea, Bacteria and mitochondria". Molecular Microbiology. 36 (1): 244–6. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01838.x. PMID 10760181.

- ^ Jansen R, Embden JD, Gaastra W, Schouls LM (March 2002). "Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes". Molecular Microbiology. 43 (6): 1565–75. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02839.x. PMID 11952905.

- ^ Mojica FJ, Díez-Villaseñor C, García-Martínez J, Soria E (February 2005). "Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 60 (2): 174–82. doi:10.1007/s00239-004-0046-3. PMID 15791728.

- ^ Pourcel C, Salvignol G, Vergnaud G (March 2005). "CRISPR elements in Yersinia pestis acquire new repeats by preferential uptake of bacteriophage DNA, and provide additional tools for evolutionary studies". Microbiology. 151 (Pt 3): 653–63. doi:10.1099/mic.0.27437-0. PMID 15758212.

- ^ Bolotin A, Quinquis B, Sorokin A, Ehrlich SD (August 2005). "Clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats (CRISPRs) have spacers of extrachromosomal origin". Microbiology. 151 (Pt 8): 2551–61. doi:10.1099/mic.0.28048-0. PMID 16079334.

- ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةcraze - ^ Sinkunas, T; Gasiunas, G; Fremaux, C; Barrangou, R; Horvath, P; Siksnys, V (Apr 2011). "Cas3 is a single-stranded DNA nuclease and ATP-dependent helicase in the CRISPR/Cas immune system". The EMBO Journal. 30 (7): 1335–42. doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.41. PMC 3094125. PMID 21343909.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Aliyari, R; Ding, SW (Jan 2009). "RNA-based viral immunity initiated by the Dicer family of host immune receptors". Immunological Reviews. 227 (1): 176–88. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00722.x. PMC 2676720. PMID 19120484.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Chylinski, K; Makarova, KS; Charpentier, E; Koonin, EV (Jun 2014). "Classification and evolution of type II CRISPR-Cas systems". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (10): 6091–105. doi:10.1093/nar/gku241. PMC 4041416. PMID 24728998.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب Makarova, KS; Aravind, L; Wolf, YI; Koonin, EV (2011). "Unification of Cas protein families and a simple scenario for the origin and evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems". Biology Direct. 6: 38. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-6-38. PMC 3150331. PMID 21756346.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ أ ب Gasiunas, G; Barrangou, R; Horvath, P; Siksnys, V (Sep 2012). "Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (39): E2579–E2586. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208507109. PMC 3465414. PMID 22949671.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Heler, R; Samai, P; Modell, JW; Weiner, C; Goldberg, GW; Bikard, D; et al. (Mar 2015). "Cas9 specifies functional viral targets during CRISPR-Cas adaptation". Nature. 519 (7542): 199–202. doi:10.1038/nature14245. PMID 25707807.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Chylinski, K; Le Rhun, A; Charpentier, E (May 2013). "The tracrRNA and Cas9 families of type II CRISPR-Cas immunity systems". RNA Biology. 10 (5): 726–37. doi:10.4161/rna.24321. PMC 3737331. PMID 23563642.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Marraffini LA (October 2015). "CRISPR-Cas immunity in prokaryotes". Nature. 526 (7571): 55–61. doi:10.1038/nature15386. PMID 26432244.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةpmid17442114 - ^ Koonin EV, Wolf YI (November 2009). "Is evolution Darwinian or/and Lamarckian?". Biology Direct. 4: 42. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-4-42. PMC 2781790. PMID 19906303.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Weiss A (October 2015). "Lamarckian Illusions". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 30 (10): 566–8. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2015.08.003. PMID 26411613.

- ^ Heidelberg JF, Nelson WC, Schoenfeld T, Bhaya D (2009). Ahmed N (ed.). "Germ warfare in a microbial mat community: CRISPRs provide insights into the co-evolution of host and viral genomes". PLoS ONE. 4 (1): e4169. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4169H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004169. PMC 2612747. PMID 19132092.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Sampson TR, Saroj SD, Llewellyn AC, Tzeng YL, Weiss DS (May 2013). "A CRISPR/Cas system mediates bacterial innate immune evasion and virulence". Nature. 497 (7448): 254–7. Bibcode:2013Natur.497..254S. doi:10.1038/nature12048. PMC 3651764. PMID 23584588.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةpmid20072129 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةpmid18065545 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةpmid18065539 - ^ Touchon M, Rocha EP (June 2010). Randau L (ed.). "The small, slow and specialized CRISPR and anti-CRISPR of Escherichia and Salmonella". PLoS ONE. 5 (6): e11126. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...511126T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011126. PMC 2886076. PMID 20559554.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةpmid17894817 - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةpmid21149389 - ^ أ ب Rho M, Wu YW, Tang H, Doak TG, Ye Y (2012). "Diverse CRISPRs evolving in human microbiomes". PLoS Genetics. 8 (6): e1002441. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002441. PMC 3374615. PMID 22719260.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ أ ب Sun CL, Barrangou R, Thomas BC, Horvath P, Fremaux C, Banfield JF (February 2013). "Phage mutations in response to CRISPR diversification in a bacterial population". Environmental Microbiology. 15 (2): 463–70. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02879.x. PMID 23057534.

- ^ Kuno S, Sako Y, Yoshida T (May 2014). "Diversification of CRISPR within coexisting genotypes in a natural population of the bloom-forming cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa". Microbiology. 160 (Pt 5): 903–16. doi:10.1099/mic.0.073494-0. PMID 24586036.

- ^ Doudna JA, Charpentier E (November 2014). "Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9". Science. 346 (6213): 1258096. doi:10.1126/science.1258096. PMID 25430774.

- ^ أ ب Ledford H (June 2015). "CRISPR, the disruptor". Nature. 522 (7554): 20–4. Bibcode:2015Natur.522...20L. doi:10.1038/522020a. PMID 26040877.

- ^ Alphey L (2016). "Can CRISPR-Cas9 gene drives curb malaria?". Nature Biotechnology. 34 (2): 149–50. doi:10.1038/nbt.3473. PMID 26849518.

- ^ Ledford, Heidi (2017). "CRISPR studies muddy results of older gene research". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.21763.

- ^ "CRISPR/Cas9 Plasmids". www.systembio.com. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ^ "CRISPR Cas9 Genome Editing". www.origene.com. OriGene. Retrieved 2015-12-17.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRan_2013 - ^ Ly, Joseph (2013). Discovering Genes Responsible for Kidney Diseases (Ph.D.). University of Toronto. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ "Scientists successfully edit human immune-system T cells | KurzweilAI". www.kurzweilai.net. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ^ Schumann K, Lin S, Boyer E, Simeonov DR, Subramaniam M, Gate RE, Haliburton GE, Ye CJ, Bluestone JA, Doudna JA, Marson A (August 2015). "Generation of knock-in primary human T cells using Cas9 ribonucleoproteins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (33): 10437–42. doi:10.1073/pnas.1512503112. PMC 4547290. PMID 26216948.

- ^ Zimmerman, Carl (Oct 15, 2015). "Editing of Pig DNA May Lead to More Organs for People". NY Times.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Hale CR, Majumdar S, Elmore J, Pfister N, Compton M, Olson S, Resch AM, Glover CV, Graveley BR, Terns RM, Terns MP (February 2012). "Essential features and rational design of CRISPR RNAs that function with the Cas RAMP module complex to cleave RNAs". Molecular Cell. 45 (3): 292–302. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.023. PMC 3278580. PMID 22227116.

- ^ Sorek R, Kunin V, Hugenholtz P (March 2008). "CRISPR--a widespread system that provides acquired resistance against phages in bacteria and archaea". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 6 (3): 181–6. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1793. PMID 18157154.

- ^ Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E (August 2012). "A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity". Science. 337 (6096): 816–21. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..816J. doi:10.1126/science.1225829. PMID 22745249.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةpmid23643243 - ^ Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, Zhang F (February 2013). "Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems". Science. 339 (6121): 819–23. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..819C. doi:10.1126/science.1231143. PMC 3795411. PMID 23287718.

- ^ Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM (February 2013). "RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9". Science. 339 (6121): 823–6. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..823M. doi:10.1126/science.1232033. PMC 3712628. PMID 23287722.

Hou Z, Zhang Y, Propson NE, Howden SE, Chu LF, Sontheimer EJ, Thomson JA (September 2013). "Efficient genome engineering in human pluripotent stem cells using Cas9 from Neisseria meningitidis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (39): 15644–9. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11015644H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1313587110. PMC 3785731. PMID 23940360. - ^ Oakes BL, Nadler DC, Flamholz A, Fellmann C, Staahl BT, Doudna JA, Savage DF (June 2016). "Profiling of engineering hotspots identifies an allosteric CRISPR-Cas9 switch". Nature Biotechnology. 34 (6): 646–51. doi:10.1038/nbt.3528. PMC 4900928. PMID 27136077.

- ^ Nuñez JK, Harrington LB, Doudna JA (March 2016). "Chemical and Biophysical Modulation of Cas9 for Tunable Genome Engineering". ACS Chemical Biology. 11 (3): 681–8. doi:10.1021/acschembio.5b01019. PMID 26857072.

- ^ Zhou W, Deiters A (April 2016). "Conditional Control of CRISPR/Cas9 Function". Angewandte Chemie. 55 (18): 5394–9. doi:10.1002/anie.201511441. PMID 26996256.

- ^ Polstein LR, Gersbach CA (March 2015). "A light-inducible CRISPR-Cas9 system for control of endogenous gene activation". Nature Chemical Biology. 11 (3): 198–200. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1753. PMC 4412021. PMID 25664691.

- ^ Nihongaki Y, Yamamoto S, Kawano F, Suzuki H, Sato M (February 2015). "CRISPR-Cas9-based photoactivatable transcription system". Chemistry & Biology. 22 (2): 169–74. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.12.011. PMID 25619936.

- ^ Wright AV, Sternberg SH, Taylor DW, Staahl BT, Bardales JA, Kornfeld JE, Doudna JA (March 2015). "Rational design of a split-Cas9 enzyme complex". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (10): 2984–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.1501698112. PMC 4364227. PMID 25713377.

- ^ Nihongaki Y, Kawano F, Nakajima T, Sato M (July 2015). "Photoactivatable CRISPR-Cas9 for optogenetic genome editing". Nature Biotechnology. 33 (7): 755–60. doi:10.1038/nbt.3245. PMID 26076431.

- ^ Hemphill J, Borchardt EK, Brown K, Asokan A, Deiters A (May 2015). "Optical Control of CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 137 (17): 5642–5. doi:10.1021/ja512664v. PMC 4919123. PMID 25905628.

- ^ Jain PK, Ramanan V, Schepers AG, Dalvie NS, Panda A, Fleming HE, Bhatia SN (September 2016). "Development of Light-Activated CRISPR Using Guide RNAs with Photocleavable Protectors". Angewandte Chemie. 55 (40): 12440–4. doi:10.1002/anie.201606123. PMID 27554600.

- ^ Gao X, Tao Y, Lamas V, Huang M, Yeh WH, Pan B, et al. (December 2017). "Treatment of autosomal dominant hearing loss by in vivo delivery of genome editing agents". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature25164. PMID 29258297.

- ^ أ ب Science News Staff (December 17, 2015). "And Science's Breakthrough of the Year is ..." news.sciencemag.org. Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- ^ Dominguez AA, Lim WA, Qi LS (January 2016). "Beyond editing: repurposing CRISPR-Cas9 for precision genome regulation and interrogation". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 17 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1038/nrm.2015.2. PMC 4922510. PMID 26670017.

- ^ Shalem O, Sanjana NE, Hartenian E, Shi X, Scott DA, Mikkelsen TS, Heckl D, Ebert BL, Root DE, Doench JG, Zhang F (January 2014). "Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells". Science. 343 (6166): 84–7. doi:10.1126/science.1247005. PMC 4089965. PMID 24336571.

- ^ أ ب Zimmer, Carl (2016-06-03). "Scientists Find Form of Crispr Gene Editing With New Capabilities". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Antonio Regalado for MIT Technology Review, March 5, 2015 Engineering the Perfect Baby

- ^ Baltimore D, Berg P, Botchan M, Carroll D, Charo RA, Church G, Corn JE, Daley GQ, Doudna JA, Fenner M, Greely HT, Jinek M, Martin GS, Penhoet E, Puck J, Sternberg SH, Weissman JS, Yamamoto KR (April 2015). "Biotechnology. A prudent path forward for genomic engineering and germline gene modification". Science. 348 (6230): 36–8. Bibcode:2015Sci...348...36B. doi:10.1126/science.aab1028. PMC 4394183. PMID 25791083.

- ^ Lanphier E, Urnov F, Haecker SE, Werner M, Smolenski J (March 2015). "Don't edit the human germ line". Nature. 519 (7544): 410–1. Bibcode:2015Natur.519..410L. doi:10.1038/519410a. PMID 25810189.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (19 March 2015). "Scientists Seek Ban on Method of Editing the Human Genome". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

The biologists writing in Science support continuing laboratory research with the technique, and few if any scientists believe it is ready for clinical use.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Talbot, David (2016). "Precise Gene Editing in Plants/ 10 Breakthrough Technologies 2016". MIT Technology review. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Larson, Christina; Schaffer, Amanda (2014). "Genome Editing/ 10 Breakthrough Technologies 2014". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

قراءات إضافية

- Sander, JD; Joung, JK (Apr 2014). "CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes". Nature Biotechnology. 32 (4): 347–55. doi:10.1038/nbt.2842. PMID 24584096.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Terns, RM; Terns, MP (Mar 2014). "CRISPR-based technologies: prokaryotic defense weapons repurposed". Trends in Genetics. 30 (3): 111–8. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2014.01.003. PMID 24555991.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Westra, ER; Buckling, A; Fineran, PC (May 2014). "CRISPR-Cas systems: beyond adaptive immunity". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 12 (5). doi:10.1038/nrmicro3241. PMID 24704746.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Horvath, P; Romero, DA; Coûté-Monvoisin, AC; Richards, M; Deveau, H; Moineau, S; et al. (Feb 2008). "Diversity, activity, and evolution of CRISPR loci in Streptococcus thermophilus". Journal of Bacteriology. 190 (4): 1401–1412. doi:10.1128/JB.01415-07. PMC 2238196. PMID 18065539.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Deveau, H; Barrangou, R; Garneau, JE; Labonté, J; Fremaux, C; Boyaval, P; et al. (Feb 2008). "Phage response to CRISPR-encoded resistance in Streptococcus thermophilus". Journal of Bacteriology. 190 (4): 1390–1400. doi:10.1128/JB.01412-07. PMC 2238228. PMID 18065545.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Andersson, AF; Banfield, JF (May 2008). "Virus population dynamics and acquired virus resistance in natural microbial communities". Science. 320 (5879): 1047–1050. doi:10.1126/science.1157358. PMID 18497291.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Hale, C; Kleppe, K; Terns, RM; Terns, MP (Dec 2008). "Prokaryotic silencing (psi)RNAs in Pyrococcus furiosus". Rna. 14 (12): 2572–2579. doi:10.1261/rna.1246808. PMC 2590957. PMID 18971321.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Carte, J; Wang, R; Li, H; Terns, RM; Terns, MP (Dec 2008). "Cas6 is an endoribonuclease that generates guide RNAs for invader defense in prokaryotes". Genes & Development. 22 (24): 3489–3496. doi:10.1101/gad.1742908. PMC 2607076. PMID 19141480.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Shah, SA; Hansen, NR; Garrett, RA (Feb 2009). "Distribution of CRISPR spacer matches in viruses and plasmids of crenarchaeal acidothermophiles and implications for their inhibitory mechanism". Biochemical Society Transactions. 37 (Pt 1): 23–28. doi:10.1042/BST0370023. PMID 19143596.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Lillestøl, RK; Shah, SA; Brügger, K; Redder, P; Phan, H; Christiansen, J; et al. (Apr 2009). "CRISPR families of the crenarchaeal genus Sulfolobus: bidirectional transcription and dynamic properties". Molecular Microbiology. 72 (1): 259–272. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06641.x. PMID 19239620.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Mojica, FJ; Díez-Villaseñor, C; García-Martínez, J; Almendros, C (Mar 2009). "Short motif sequences determine the targets of the prokaryotic CRISPR defence system". Microbiology. 155 (Pt 3): 733–740. doi:10.1099/mic.0.023960-0. PMID 19246744.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - van der Ploeg, JR (Jun 2009). "Analysis of CRISPR in Streptococcus mutans suggests frequent occurrence of acquired immunity against infection by M102-like bacteriophages". Microbiology. 155 (Pt 6): 1966–1976. doi:10.1099/mic.0.027508-0. PMID 19383692.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Hale, CR; Zhao, P; Olson, S; Duff, MO; Graveley, BR; Wells, L; et al. (Nov 2009). "RNA-guided RNA cleavage by a CRISPR RNA-Cas protein complex". Cell. 139 (5): 945–956. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.040. PMC 2951265. PMID 19945378.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - van der Oost, J; Brouns, SJ (Nov 2009). "RNAi: prokaryotes get in on the act". Cell. 139 (5): 863–865. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.018. PMID 19945373.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Marraffini, LA; Sontheimer, EJ (Jan 2010). "Self versus non-self discrimination during CRISPR RNA-directed immunity". Nature. 463 (7280): 568–571. doi:10.1038/nature08703. PMC 2813891. PMID 20072129.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Karginov, FV; Hannon, GJ (Jan 2010). "The CRISPR system: small RNA-guided defense in bacteria and archaea". Molecular Cell. 37 (1): 7–19. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.033. PMC 2819186. PMID 20129051.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Pul, U; Wurm, R; Arslan, Z; Geissen, R; Hofmann, N; Wagner, R (Mar 2010). "Identification and characterization of E. coli CRISPR-cas promoters and their silencing by H-NS". Molecular Microbiology. 75 (6): 1495–1512. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07073.x. PMID 20132443.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Díez-Villaseñor, C; Almendros, C; García-Martínez, J; Mojica, FJ (May 2010). "Diversity of CRISPR loci in Escherichia coli". Microbiology. 156 (Pt 5): 1351–1361. doi:10.1099/mic.0.036046-0. PMID 20133361.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Deveau, H; Garneau, JE; Moineau, S (2010). "CRISPR/Cas system and its role in phage-bacteria interactions". Annual Review of Microbiology. 64: 475–493. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134123. PMID 20528693.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Koonin, EV; Makarova, KS (Dec 2009). "CRISPR-Cas: an adaptive immunity system in prokaryotes". F1000 Biology Reports. 1: 95. doi:10.3410/B1-95. PMC 2884157. PMID 20556198.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Touchon, M; Rocha, EP (2010). Randau, Lennart (ed.). "The small, slow and specialized CRISPR and anti-CRISPR of Escherichia and Salmonella". PloS One. 5 (6): e11126. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011126. PMC 2886076. PMID 20559554.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

- Pages with incomplete PMID references

- CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Protein articles without symbol

- Protein pages needing a picture

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2016

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages using div col with unknown parameters