فضاء متري

في الرياضيات ، دالة المسافة distance function أو المترية metric هي دالة رياضية تعرف المسافة بين العناصر ضمن مجموعة ما .

أي مجموعة مزودة بتابع مسافة تدعى فضاءا متريا metric space. هذه المترية أو دالة المسافة هي التي تخلق طوبولوجيا ضمن هذه المجموعة (أي أنها تحول هذه المجموعة إلى فضاء طوبولوجي), لكن العكس غير صحيح فليست كل طوبولوجيا يتم تشكيلها بوساطة مترية .

عندما تكون الطوبولوجيا قابلة للوصف بوساطة متري نقول أن هذا الفضاء قابل للقياس (مقيس) metrisable .

The most familiar example of a metric space is 3-dimensional Euclidean space with its usual notion of distance. Other well-known examples are a sphere equipped with the angular distance and the hyperbolic plane. A metric may correspond to a metaphorical, rather than physical, notion of distance: for example, the set of 100-character Unicode strings can be equipped with the Hamming distance, which measures the number of characters that need to be changed to get from one string to another.

Since they are very general, metric spaces are a tool used in many different branches of mathematics. Many types of mathematical objects have a natural notion of distance and therefore admit the structure of a metric space, including Riemannian manifolds, normed vector spaces, and graphs. In abstract algebra, the p-adic numbers arise as elements of the completion of a metric structure on the rational numbers. Metric spaces are also studied in their own right in metric geometry[1] and analysis on metric spaces.[2]

Many of the basic notions of mathematical analysis, including balls, completeness, as well as uniform, Lipschitz, and Hölder continuity, can be defined in the setting of metric spaces. Other notions, such as continuity, compactness, and open and closed sets, can be defined for metric spaces, but also in the even more general setting of topological spaces.

تعريف

الدافع

To see the utility of different notions of distance, consider the surface of the Earth as a set of points. We can measure the distance between two such points by the length of the shortest path along the surface, "as the crow flies"; this is particularly useful for shipping and aviation. We can also measure the straight-line distance between two points through the Earth's interior; this notion is, for example, natural in seismology, since it roughly corresponds to the length of time it takes for seismic waves to travel between those two points.

The notion of distance encoded by the metric space axioms has relatively few requirements. This generality gives metric spaces a lot of flexibility. At the same time, the notion is strong enough to encode many intuitive facts about what distance means. This means that general results about metric spaces can be applied in many different contexts.

Like many fundamental mathematical concepts, the metric on a metric space can be interpreted in many different ways. A particular metric may not be best thought of as measuring physical distance, but, instead, as the cost of changing from one state to another (as with Wasserstein metrics on spaces of measures) or the degree of difference between two objects (for example, the Hamming distance between two strings of characters, or the Gromov–Hausdorff distance between metric spaces themselves).

التعريف

المترية على المجموعة X دالة رياضية (تدعى أيضا دالة المسافة)

d : X × X → R

(حيث R مجموعة الأعداد الحقيقية). من أجل x, y, z ضمن X, يقتضي هذه الدالة تحقيق الشروط التالية :

- d(x, y) ≥ 0 ( اللاسلبية )

- d(x, y) = 0 if and only if x = y ()

- d(x, y) = d(y, x) (التناظر)

- d(x, z) ≤ d(x, y) + d(y, z) (لامساواة المثلث).

فضاءات الطول

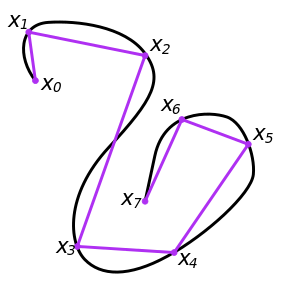

A curve in a metric space (M, d) is a continuous function . The length of γ is measured by

In general, this supremum may be infinite; a curve of finite length is called rectifiable.[3] Suppose that the length of the curve γ is equal to the distance between its endpoints—that is, it's the shortest possible path between its endpoints. After reparametrization by arc length, γ becomes a geodesic: a curve which is a distance-preserving function.[4] A geodesic is a shortest possible path between any two of its points.[أ]

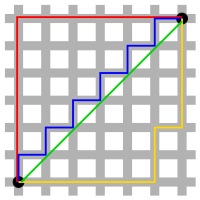

A geodesic metric space is a metric space which admits a geodesic between any two of its points. The spaces and are both geodesic metric spaces. In , geodesics are unique, but in , there are often infinitely many geodesics between two points, as shown in the figure at the top of the article.

The space M is a length space (or the metric d is intrinsic) if the distance between any two points x and y is the infimum of lengths of paths between them. Unlike in a geodesic metric space, the infimum does not have to be attained. An example of a length space which is not geodesic is the Euclidean plane minus the origin: the points (1, 0) and (-1, 0) can be joined by paths of length arbitrarily close to 2, but not by a path of length 2. An example of a metric space which is not a length space is given by the straight-line metric on the sphere: the straight line between two points through the center of the Earth is shorter than any path along the surface.

Given any metric space (M, d), one can define a new, intrinsic distance function dintrinsic on M by setting the distance between points x and y to be infimum of the d-lengths of paths between them. For instance, if d is the straight-line distance on the sphere, then dintrinsic is the great-circle distance. However, in some cases dintrinsic may have infinite values. For example, if M is the Koch snowflake with the subspace metric d induced from , then the resulting intrinsic distance is infinite for any pair of distinct points.

طيات ريمان

A Riemannian manifold is a space equipped with a Riemannian metric tensor, which determines lengths of tangent vectors at every point. This can be thought of defining a notion of distance infinitesimally. In particular, a differentiable path in a Riemannian manifold M has length defined as the integral of the length of the tangent vector to the path:

On a connected Riemannian manifold, one then defines the distance between two points as the infimum of lengths of smooth paths between them. This construction generalizes to other kinds of infinitesimal metrics on manifolds, such as sub-Riemannian and Finsler metrics.

The Riemannian metric is uniquely determined by the distance function; this means that in principle, all information about a Riemannian manifold can be recovered from its distance function. One direction in metric geometry is finding purely metric ("synthetic") formulations of properties of Riemannian manifolds. For example, a Riemannian manifold is a CAT(k) space (a synthetic condition which depends purely on the metric) if and only if its sectional curvature is bounded above by k.[7] Thus CAT(k) spaces generalize upper curvature bounds to general metric spaces.

التاريخ

This section requires expansion with: Reasons for generalizing the Euclidean metric, first non-Euclidean metrics studied, consequences for mathematics. (August 2011) |

In 1906 Maurice Fréchet introduced metric spaces in his work Sur quelques points du calcul fonctionnel[8] in the context of functional analysis: his main interest was in studying the real-valued functions from a metric space, generalizing the theory of functions of several or even infinitely many variables, as pioneered by mathematicians such as Cesare Arzelà. The idea was further developed and placed in its proper context by Felix Hausdorff in his magnum opus Principles of Set Theory, which also introduced the notion of a (Hausdorff) topological space.[9]

General metric spaces have become a foundational part of the mathematical curriculum.[10] Prominent examples of metric spaces in mathematical research include Riemannian manifolds and normed vector spaces, which are the domain of differential geometry and functional analysis, respectively.[11] Fractal geometry is a source of some exotic metric spaces. Others have arisen as limits through the study of discrete or smooth objects, including scale-invariant limits in statistical physics, Alexandrov spaces arising as Gromov–Hausdorff limits of sequences of Riemannian manifolds, and boundaries and asymptotic cones in geometric group theory. Finally, many new applications of finite and discrete metric spaces have arisen in computer science.

انظر أيضاً

- Acoustic metric

- Complete metric

- Diversity (mathematics)

- Glossary of Riemannian and metric geometry

- Hilbert's fourth problem

- Metric tree

- Minkowski distance

- Signed distance function

- Similarity measure

- Space (mathematics)

- Ultrametric space

ملاحظات

- ^ This differs from usage in Riemannian geometry, where geodesics are only locally shortest paths. Some authors define geodesics in metric spaces in the same way.[5][6]

الهامش

- ^ Burago, Burago & Ivanov 2001.

- ^ Heinonen 2001.

- ^ Burago, Burago & Ivanov 2001, Definition 2.3.1.

- ^ Margalit & Thomas 2017.

- ^ Burago, Burago & Ivanov 2001, Definition 2.5.27.

- ^ Gromov 2007, Definition 1.9.

- ^ Burago, Burago & Ivanov 2001, p. 127.

- ^ Fréchet, M. (December 1906). "Sur quelques points du calcul fonctionnel". Rendiconti del Circolo Matematico di Palermo. 22 (1): 1–72. doi:10.1007/BF03018603. S2CID 123251660.

- ^ Blumberg, Henry (1927). "Hausdorff's Grundzüge der Mengenlehre". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 6: 778–781. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1920-03378-1.

- ^ Rudin 1976, p. 30.

- ^ E.g. Burago, Burago & Ivanov 2001, p. xiii:

... for most of the last century it was a common belief that "geometry of manifolds" basically boiled down to "analysis on manifolds". Geometric methods heavily relied on differential machinery, as can be guessed from the name "Differential geometry".

المراجع

- Aldrovandi, Ruben; Pereira, José Geraldo (2017), An Introduction to Geometrical Physics (2nd ed.), Hackensack, New Jersey: World Scientific, p. 20, ISBN 978-981-3146-81-5, https://books.google.com/books?id=NWhtDQAAQBAJ&pg=PA20

- Arkhangel'skii, A. V.; Pontryagin, L. S. (1990), General Topology I: Basic Concepts and Constructions Dimension Theory, Encyclopaedia of Mathematical Sciences, Springer, ISBN 3-540-18178-4

- Bryant, Victor (1985). Metric spaces: Iteration and application. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-31897-1.

- Buldygin, V. V.; Kozachenko, Yu. V. (2000), Metric Characterization of Random Variables and Random Processes, Translations of Mathematical Monographs, 188, Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society, p. 129, doi:, ISBN 0-8218-0533-9, https://books.google.com/books?id=ePDXvIhdEjoC&pg=PA129

- Burago, Dmitri; Burago, Yuri; Ivanov, Sergei (2001). A course in metric geometry. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0-8218-2129-6.

- Čech, Eduard (1969). Point Sets. Academic Press. ISBN 0121648508.

- Cohen, Andrew R.; Vitányi, Paul M. B. (2012), "Normalized compression distance of multisets with applications", IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 37 (8): 1602–1614, doi:, PMID 26352998

- Deza, Michel Marie; Laurent, Monique (1997), Geometry of Cuts and Metrics, Algorithms and Combinatorics, 15, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, p. 27, doi:, ISBN 3-540-61611-X, https://books.google.com/books?id=XujvCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA27

- Fraigniaud, P.; Lebhar, E.; Viennot, L. (2008), "The inframetric model for the internet", 2008 IEEE INFOCOM - The 27th Conference on Computer Communications, pp. 1085–1093, doi:, ISBN 978-1-4244-2026-1

- Gromov, Mikhael (2007). Metric structures for Riemannian and non-Riemannian spaces. Boston: Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-0-8176-4582-3.

- Heinonen, Juha (2001). Lectures on analysis on metric spaces. New York: Springer. ISBN 0-387-95104-0.

- Heinonen, Juha (24 January 2007). "Nonsmooth calculus". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 44 (2): 163–232. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-07-01140-8.

- Helemskii, A. Ya. (2006), Lectures and Exercises on Functional Analysis, Translations of Mathematical Monographs, 233, Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society, p. 14, doi:, ISBN 978-0-8218-4098-6, https://books.google.com/books?id=wjzZCLzx6hUC&pg=PA14

- Pascal Hitzler; Anthony Seda (19 April 2016). Mathematical Aspects of Logic Programming Semantics. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-2962-2.

- Lawvere, F. William (December 1973). "Metric spaces, generalized logic, and closed categories". Rendiconti del Seminario Matematico e Fisico di Milano. 43 (1): 135–166. doi:10.1007/BF02924844. S2CID 1845177.

- Margalit, Dan; Thomas, Anne (2017). "Office Hour 7. Quasi-isometries". Office hours with a geometric group theorist. Princeton University Press. pp. 125–145. ISBN 978-1-4008-8539-8. JSTOR j.ctt1vwmg8g.11.

- قالب:Munkres Topology

- قالب:Narici Beckenstein Topological Vector Spaces

- Ó Searcóid, Mícheál (2006). Metric spaces. London: Springer. ISBN 1-84628-369-8.

- Papadopoulos, Athanase (2014). Metric spaces, convexity, and non-positive curvature (Second ed.). Zürich, Switzerland: European Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-3-03719-132-3.

- Rolewicz, Stefan (1987). Functional Analysis and Control Theory: Linear Systems. Springer. ISBN 90-277-2186-6.

- Rudin, Walter (1976). Principles of Mathematical Analysis (Third ed.). New York. ISBN 0-07-054235-X. OCLC 1502474.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Smyth, M. (1988), "Quasi uniformities: reconciling domains with metric spaces", in Main, M.; Melton, A.; Mislove, M. et al., Mathematical Foundations of Programming Language Semantics, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 298, Springer-Verlag, pp. 236–253, doi:, ISBN 978-3-540-19020-2

- Steen, Lynn Arthur; Seebach, J. Arthur Jr. (1995) [1978]. Counterexamples in Topology. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-68735-3. MR 0507446.

- Vitányi, Paul M. B. (2011). "Information distance in multiples". IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 57 (4): 2451–2456. arXiv:0905.3347. doi:10.1109/TIT.2011.2110130. S2CID 6302496.

- Väisälä, Jussi (2005). "Gromov hyperbolic spaces" (PDF). Expositiones Mathematicae. 23 (3): 187–231. doi:10.1016/j.exmath.2005.01.010. MR 2164775.

- Vickers, Steven (2005). "Localic completion of generalized metric spaces, I". Theory and Applications of Categories. 14 (15): 328–356. MR 2182680.

- Eric W. Weisstein, Product Metric at MathWorld.

- Xia, Qinglan (2008). "The geodesic problem in nearmetric spaces". Journal of Geometric Analysis. 19 (2): 452–479. arXiv:0807.3377. doi:10.1007/s12220-008-9065-4. S2CID 17475581.

- Xia, Q. (2009). "The geodesic problem in quasimetric spaces". Journal of Geometric Analysis. 19 (2): 452–479. arXiv:0807.3377. doi:10.1007/s12220-008-9065-4. S2CID 17475581.

وصلات خارجية

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Metric space", Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1556080104

- Far and near—several examples of distance functions at cut-the-knot.

خطأ لوا في وحدة:Authority_control على السطر 278: attempt to call field '_showMessage' (a nil value).

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles to be expanded from August 2011

- All articles to be expanded

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- Metric spaces

- Mathematical analysis

- Mathematical structures

- Topological spaces

- Uniform spaces

- هندسة مترية

- طوبولوجيا